thats the baby boomers..

we ain't got a clue how much damage they really did...

link is a long read, imma just post a little bit of it....

Decivilization in the 1960s

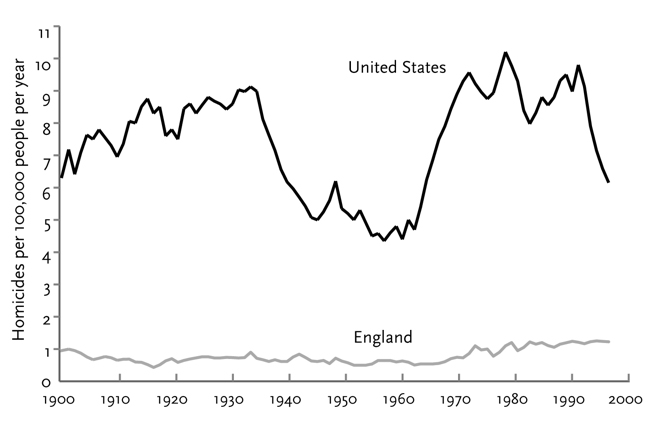

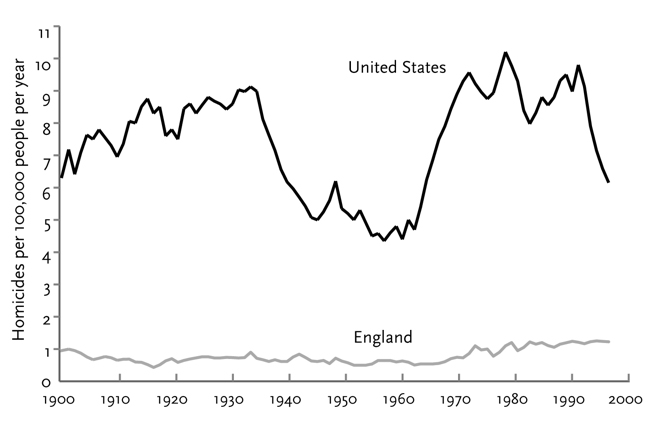

And figure two, Homicide rates in US and England 1900-2000, shows that in the 1960s the homicide rate in America went through the roof.

Figure two - Homicide rates in US and England 1900-2000

After a three-decade free fall that spanned the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War, Americans multiplied their homicide rate by more than two and a half, from a low of 4.0 in 1957 to a high of 10.2 in 1980 (U.S. Bureau of Statistics; Fox and Zawitz: 2007). The upsurge included every other category of major crime as well, including rape, assault, robbery, and theft, and lasted (with ups and downs) for three decades. The cities got particularly dangerous, especially New York, which became a symbol of the new criminality.

Though the surge in violence affected all the races and both genders, it was most dramatic among black men, whose annual homicide rate had shot up by the mid-1980s to 72 per 100,000.

The flood of violence from the 1960s through the 1980s reshaped American culture, the political scene, and everyday life. Mugger jokes became a staple of comedians, with mentions of Central Park getting an instant laugh as a well-known death trap. New Yorkers imprisoned themselves in their apartments with batteries of latches and deadbolts, including the popular “police lock,” a steel bar with one end anchored in the floor and the other propped up against the door. The section of downtown Boston not far from where I now live was called the Combat Zone because of its endemic muggings and stabbings. Urbanites quit other American cities in droves, leaving burned-out cores surrounded by rings of suburbs, exurbs, and gated communities. Books, movies and television series used intractable urban violence as their backdrop, including Little Murders, Taxi Driver, The Warriors, Escape from New York, Fort Apache the Bronx, Hill Street Blues, and Bonfire of the Vanities. Women enrolled in self-defense courses to learn how to walk with a defiant gait, to use their keys, pencils, and spike heels as weapons, and to execute karate chops or jujitsu throws to overpower an attacker, role-played by a volunteer in a Michelin-man-tire suit. Red-bereted Guardian Angels patrolled the parks and the mass transit system, and in 1984 Bernhard Goetz, a mild-mannered engineer, became a folk hero for shooting four young muggers in a New York subway car. A fear of crime helped elect decades of conservative politicians, including Richard Nixon in 1968 with his “Law and Order” platform (overshadowing the Vietnam War as a campaign issue); George H. W. Bush in 1988 with his insinuation that Michael Dukakis, as governor of Massachusetts, had approved a prison furlough program that had released a rapist; and many senators and congressmen who promised to “get tough on crime.” Though the popular reaction was overblown—far more people are killed every year in car accidents than in homicides, especially among those who don’t get into arguments with young men in bars—the sense that violent crime had multiplied was not a figment of their imaginations.

The rebounding of violence in the 1960s defied every expectation. The decade was a time of unprecedented economic growth, nearly full employment, levels of economic equality for which people today are nostalgic, historic racial progress, and the blossoming of government social programs, not to mention medical advances that made victims more likely to survive being shot or knifed. Social theorists in 1962 would have happily bet that these fortunate conditions would lead to a continuing era of low crime. And they would have lost their shirts.

Why did the Western world embark on a three-decade binge of crime from which it has never fully recovered? This is one of several local reversals of the long-term decline of violence that I will examine in this book. If the analysis is on the right track, then the historical changes I have been invoking to explain the decline should have gone into reverse at the time of the surges.

An obvious place to look is demographics. The 1940s and 1950s, when crime rates hugged the floor, were the great age of marriage. Americans got married in numbers not seen before or since, which removed men from the streets and planted them in suburbs (Courtwright 1996). One consequence was a bust in violence. But the other was a boom in babies. The first baby boomers, born in 1946, entered their crime-prone years in 1961; the ones born in the peak year, 1954, entered in 1969. A natural conclusion is that the crime boom was an echo of the baby boom. Unfortunately, the numbers don’t add up.

If it were just a matter of there being more teenagers and twenty-somethings who were committing crimes at their usual rates, the increase in crime from 1960 to 1970 would have been 13 percent, not 135 percent.[2] Young men weren’t simply more numerous than their predecessors; they were more violent, too.

and their dikkriders trying to find every single excuse to downplay whats posted in the OP. Face it people the myth that rap music is the purpose for crime in the black community has been busted many times. Poverty causes crime, get over it already.

and their dikkriders trying to find every single excuse to downplay whats posted in the OP. Face it people the myth that rap music is the purpose for crime in the black community has been busted many times. Poverty causes crime, get over it already.