Andrew Lam

Andrew Lam

Almost 4 decades ago, fresh from the refugee camp of Vietnam, I was first made acutely aware of my own Asian looks by a schoolyard bully in my junior high in Colma, California. He pulled the sides of his eyes back to make them look slanted and sang the well-known bully's ditty "Ching Chong, Ching Chong, Chinaman."

I never thought of how I looked living in homogenous Saigon, but in America, as an outsider barely speaking English, I was fodder for teasing and racist epithets. In the bathroom one night some years later, as a teenager wanting to fit in, I used a toothpick to push up my epicanthic folds. They held for a few seconds, giving me the appearance of rounder eyes, and a glimpse of what I might look like with double eyelids. I had contemplated cosmetic surgery, and for a few months, even saved money for the purpose.

I never went through with the surgery, but my experience is hardly unique. The pressure to alter one's features and body is endemic in every group and ethnic community in America, and in Asia it is as routine as having one's wisdom teeth pulled. But the number of minorities getting plastic surgery is apparently on a steep rise.

According to a survey by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), in 2005 Asian-Americans had 437,000 cosmetic surgeries. In 2010, the number has risen to 760,691 - almost doubled in 5 years. One only needs to open a Vietnamese or Chinese or Korean language magazines Orange County to see the onslaught of ads for cosmetic surgery: eyebrow tattoos, dimple and split chin fabrications, laser treatments for skin blemishes, facelifts, breast augmentations -- you can have it all and with an easy-to-pay credit plan. But the most popular are nose and eye surgeries. In the online business directory of Little Saigon in Orange County, where the largest Vietnamese population in the United States resides, there are more than 50 local listings for cosmetic improvements and surgery.

Looking at some of these ads, I must admit that I find both the "before" and "after" pictures slightly disturbing. In the "before," which is often out of focus, the woman is displayed in a downtrodden, bereft look -- a mess of misery to go with her messy hair. But in the "after" picture, she is all smiles, well-dressed and coiffed.

She poses in a kind of exaggerated cheerfulness -- cheerful, I suppose, because her features have been altered. Apparently along with the surgery, the image suggests, her outlooks on life has dramatically changed as well.

I wish happiness were so easily obtained. While I am not against it, and have friends and loved ones who have had plastic surgery, I can't help but find that there's an inherent complex attached to altering one's facial features -- especially for an Asian-American. After all, I have never heard of someone who goes under the knife to have a double-eyelid reversal surgery or his classic roman nose flattened.

For a long time plastic surgeons worked with the Anglo-Saxon ideal of beauty, and medical schools a few decades ago did not acknowledge racial distinctions when it came to plastic surgery. Going under the knife in the name of beauty was, for a long time, a move toward having a Caucasian face.

Indeed, Asia's relationship with the West has been traditionally schizophrenic and contradictory when it comes to self-image. Vietnamese children of mixed parentage born of American GIs during the war, for instance, were a permanent under class, and their conditions worsened after the war ended. Perceived as children of the enemy, they were often derided, chastised and beaten. But these days those mixed children's features are coveted by many wealthy people in Saigon and Hanoi. They want their noses, eyes, lips, and would save a fortune to go under the knife to look like them.

Or take Japanese animation. While Japanese cartoons and comic books are taking the world over by storm -- and are a source of pride for Japan -- on closer inspection, one wonders if such pride is fully justified.

The author a few years ago at Petra, Jordan

Characters in popular animes like Inuyahsa or Naruto, just to name a few, all have round, large eyes that are often blue or green, and their hair is blond, brown or red. Japan, even as it struggles to make itself a global political player, by the look of its manga and anime, seems strangely beholden to the visage of their World War II conquerors.

In Korea, one in five women has

gone under the knife. Seoul, in fact, has become the cosmetic surgery meccas for East Asians, if not the entire world, where those who could afford it, fly to South Korea to spend a fortune for a complete make over. China, since a ban on cosmetic surgery was lifted in 2001, is now experiencing a boom in the cosmetic surgery industry. There are more than 10,000 medical institutions for cosmetic surgery and the industry is thriving. There is even, since 2004, a

Miss Plastic Surgery beauty contest.

However, there is a new "Look East" movement underfoot -- a growing Asian social consciousness in the United States and Asia. Plastic surgeons have begun to develop techniques to preserve ethnic characteristics and retain their identity. The changes are now more subtle: the nose is no longer as pointy, and doctors are not removing as much fat near the lower eyelid to avoid "the Caucasian look."

"Ethnic correctness" is the new catch phrase in cosmetic surgery, noted Audrey Magazine, a fashion magazine for Asian-American readers. "With a growing appreciation for diversity and a higher social awareness come advances in technique and deeper understanding of the anatomy of the Asian eye, resulting in more ethnically sensitive procedures."

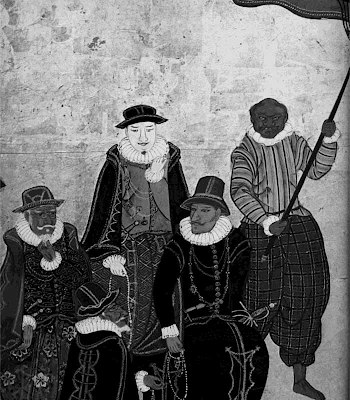

The above Chinese woman was sued by her husband who didn't know that she has had extensive cosmetic surgery in South Korea before they married.

A Chinese-American friend, who has had excess fat removed from her eyelids, told me she never thought she wanted to "look white." "In fact, I wanted to look natural but better. So if no one noticed I had it done, then that's great." It was the older generation, she said, that was obsessed with "looking like Audrey Hepburn and Kim Novak."

It also helps that many young Asian entertainers have resisted cosmetic surgery. Korean pop stars have been the rage in Asia as well as among Asian immigrants in America, and on top of that food chain is the 27-year-old superstar Rain, whose classic Korean features haven't deterred fans in the least. He's often thought of as the Michael Jackson of Asia, sans the plastic surgery knife. And, of course, there's Psy, whose Gangnam Style video became the biggest hit in Youtube history, who doesn't seem very concerned very much with the standardized ideas of beauty.

And Zhang Ziyi ("Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon"), Sandra Oh ("Sideways" and "Grey's Anatomy") and Lucy Liu ("Charlie's Angels"), to name a few, are famous actresses with very distinctive Asian features.

Plasticsurgery.org noted that Asians like "to maintain their ethnic identity. They do not want to lose important facial features that exhibit racial character. For instance, the typical Asian patient who has eyelid surgery desires a wider, fuller eye that is natural looking to the Asian face and maintains an almond shape."

These days I am comfortable in my own skin, and I take comfort in knowing that there are more people who look like me in the world than not. Having traveled throughout Asia over the years, my sense of beauty has become pluralized, and is no longer limited to a singular ideal.