You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Where was hip-hop created?

- Thread starter Neuromancer

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?No he wasn't because he was dapping ALL the wrong info in this thread!Pretty sure he was being sarcastic

So lets get this right. You think a poor small island like Jamaica with only 2million people is gonna have more stable electricity then a money making city of 8 million people?Didnt New York have crazy blackouts around that time, too?

How you setting up sound systems with no electricity?

And no, it was the blackout of 1977 that you are speaking about. Black outs are not common!

You might be trolling because no one is this damn dumb, so I'm not answering you anymore

Sankofa Alwayz

#FBADOS #B1 #D(M)V #KnowThyself #WaveGod

Sankofa Alwayz

#FBADOS #B1 #D(M)V #KnowThyself #WaveGod

Where is Puerto Rico located?

Be intellectually challenged brehs.

Sankofa Alwayz

#FBADOS #B1 #D(M)V #KnowThyself #WaveGod

nikka said dancing and having a good time came from Jamaica

Fool tried it tryna be serious wit it

It was cute, but nah

It was cute, but nah

Sankofa Alwayz

#FBADOS #B1 #D(M)V #KnowThyself #WaveGod

Mans really think people were dancing and having a good time in cold ass NYC before the Jamaicains arrived?

Yo ass is from grey, cool, rain-prone London living under a climate akin to the American Pacific Northwest. I know damn well yo ass ain’t talking shyt about NY’s weather slim

You a clown for walking into that.

You a clown for walking into that.IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Especially @ 18:30 in the video.

aframs were doing toasts/toasting/wordplay/banter decades prior to when jamaica picked up on the southern afram tradition.

and

The Dozens: A History of Rap's Mama

Following his groundbreaking explorations of the blues and American popular music in Escaping the Delta and How the Beatles Destroyed Rock 'n' Roll, Elijah Wald turns his attention to the tradition of African American street rhyming and verbal combat that ruled urban neighborhoods long before rap: the viciously funny, outrageously inventive insult game called "the dozens." At its simplest, the dozens is a comic concatenation of "yo' mama" jokes. At its most complex, it is a form of social interaction that reaches back to African ceremonial rituals. Whether considered vernacular poetry, verbal dueling, a test of street cool, or just a mess of dirty insults, the dozens has been a basic building block of African-American culture. A game which could inspire raucous laughter or escalate to violence, it provided a wellspring of rhymes, attitude, and raw humor that has influenced pop musicians from Jelly Roll Morton to Ice Cube. Wald explores the depth of the dozens' roots, looking at mother-insulting and verbal combat from Greenland to the sources of the Niger, and shows its breadth of influence in the seminal writings of Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston; the comedy of Richard Pryor and George Carlin; the dark humor of the blues; the hip slang and competitive jamming of jazz; and most recently in the improvisatory battling of rap. A forbidden language beneath the surface of American popular culture, the dozens links children's clapping rhymes to low-down juke joints and the most modern street verse to the earliest African American folklore. In tracing the form and its variations over more than a century of African American culture and music, The Dozens sheds fascinating new light on schoolyard games and rural work songs, serious literature and nightclub comedy, and pop hits from ragtime to rap

The dozens as American art form: No, your mama!

You can’t understand hip-hop without understanding the insult-battle tradition, says Elijah Wald

In 1939, a Yale psychologist named John Dollard traveled to the Jim Crow South to study the personality development of black children. Over and over again, he found something he hadn’t been looking for. On street corners and in schoolyards, in big cities and small towns, among the young and old alike, he found black folks facing off in games of street banter that followed specific rules: two players, fueled by the reaction of a gathered crowd, insulting each other in rhyme. The more ingenious the insult, the better.

What Dollard had stumbled on—and breathlessly described in a psychoanalytic journal—was a tradition that influenced Langston Hughes in the 1920s, made Richard Pryor a legend in the 1970s, and continues to fuel rap beefs today: the dozens.

“The Dozens is a pattern of interactive insult which is used among some American Negroes,” Dollard reported, in the first known article written about the street-rhyme combat typically touched off by two little words: yo’ mama. “The jests fly—about infidelity, though each seems a faithful husband—about impotence, though both are apparently adequately married and have children—about homosexual tendencies, although neither exhibits such to public perception.” Not to mention mothers, sisters, and girlfriends being stupid, raunchy, or just plain old ugly.

In “The Dozens: A History of Rap’s Mama,” writer, musician, and blues scholar Elijah Wald traces the comic and profane arc of the dozens clear through African-American culture—through rural works songs and the competitive jamming of jazz masters, through Mississippi barrelhouse songs and the iconic literature of the Harlem Renaissance. “No one has attempted a serious historical insult mapping of the United States,” Wald cautions in his book, and yet “The Dozens” ambitiously charts such a geography, outlining a heritage of verbal smack-downs from West African insult games to “Welcome Back, Kotter,” from jump-rope rhymes to rapper Grandmaster Flash to YouTube. Along the way, Wald’s underlying argument emerges with its own distinct challenge: It’s precisely the raw, filthy, unprintable essence of the dozens that makes it so important to preserve.

“It’s a lot more interesting than just a bunch of dirty jokes,” Wald said in an interview. “There’s a rich and complex history around it that tells a story about who we are. Not talking about this stuff just means not knowing how our culture happened.”

Wald spoke to Ideas from his home in Medford.

IDEAS: So, how does a middle-aged white guy find himself writing a book about the dozens?

The dozens is ‘about saying something not only nasty enough so that the other guy can’t think what to say, but also funny enough that the audience thinks that you’ve just done something smart.’

WALD: A few years ago it struck me that rap had opened up the possibility of doing a completely different history of African-American music. Because the way we’ve written the history of African-American music was, first of all, the roots of jazz. And then we wrote it as the roots of rock. And what that left out was all of the recitations that didn’t have melody, which was a huge tradition in African-American arts....And so I said, wait a minute: I’m supposed to be a historian of popular music. Let’s go back and see where this came from.

IDEAS: In your book, you make the case that the dozens can be traced back to African oral traditions.

WALD: That wasn’t something I was sure I believed when I started, because there’s this tendency to try to trace everything back to Africa. And as a historian, I’m always nervous about that stuff because I always think myths that make people feel good get encouraged, and sometimes they’re just there to make people feel good. But the more I looked at African stuff it was everywhere.

IDEAS: What were you finding?

WALD: It’s very deep in ceremonies. So that for example, you find circumcision ceremonies where part of the ritual songs that boys sing following the ceremony have lines [insulting] your mother, which I found partly interesting because sociologists have often suggested that the dozens is sort of an adolescent ritual whereby boys cut themselves off from their mothers and become part of the gang....There’s also the fact that versions of this are everywhere in the [black] diaspora in the Americas, no matter what language you’re in.

IDEAS: You call the dozens a basic building block of African-American culture. How widespread was its influence?

WALD: You find it everywhere. It’s in black comedy—Richard Pryor, Redd Foxx. Eddie Murphy, who is coming straight out of the dozens. Rap battling is clearly the dozens....But also just the extent to which, for example, when I started looking through writers from the Harlem Renaissance, there’s a dozens scene in virtually every book....Langston Hughes, his last cycle of poems was called “Ask Your Mama,” and it was his poems about living surrounded by white people on Long Island, which is where he had retired to. And it’s all about, “They rung my bell to ask me/ Could I recommend a maid./ I said, yes, your mama.”

IDEAS: Do you agree with Dollard’s 1939-era notion that the dozens acted as a safety valve, a safe space where blacks could be aggressive without consequences?

WALD: Well, it also gets framed in black culture very often as training on how not to lose it if somebody said something really horrible to you. And that’s something you find [recurring] a lot in older black people, saying the dozens is—it’s not pretty, but this was something young black men had to deal with, people saying vile stuff to them every day of their lives. And this was a form of training to learn not to lose it when somebody says something to you. Within the black community there have been arguments for why the dozens served a social function before the sociologists got into it.

IDEAS: Because so much of this tradition has been unwritten or censored, is it even possible to pinpoint the emergence of the dozens in American popular culture?

WALD: The first time the dozens was ever defined in print is in sheet music for a song called “Don’t Slip Me In the Dozen, Please,” from 1921. Then [blues singer] Speckled Red had this huge hit in 1929 with a song called “The Dirty Dozens.” And then there were like 20 covers and follow-up and answer songs, and everybody in the blues started doing their dozens song.

IDEAS: How does the dozens live on today in hip-hop beefs?

WALD: I would say the main thing that it has to do with beefs is just that this is where people often go with beefs: It often gets into mothers and girlfriends or whatever. But I don’t think beefs is really that similar to the dozens. Beefs is people who are genuinely angry with each other. Rap battling is really what’s more like the dozens. Because people battle and sometimes they genuinely dislike each other, but sometimes they’re really good friends. And if they’re good battlers, you can’t tell which you’re watching, because either way they’re going to...say the nastiest things they can think of, and that’s really how the dozens works: It’s about the creativity. It’s about saying something not only nasty enough so that the other guy can’t think what to say, but also funny enough that the audience thinks that you’ve just done something smart. That’s the combination at the heart of the dozens.

The dozens as American art form: No, your mama! - The Boston Globe

to

What’s irritating about this myth that keeps being perpetuated is that this aspect of the culture is more than music. It’s everyday life shyt. The idea that this found its way into AA culture by way of some Jamaicans in 1970’s NYC is damn near COMICAL when you know better.

cat's have been hearing the repeated mythical, hiphop origin myths so long, they don't know any different, which is sad because the truth is out there straight from the OG's mouth's if you bothered to look for it

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Didnt New York have crazy blackouts around that time, too?

How you setting up sound systems with no electricity?

blackout happened in 1977 which led to the surge in people having more/better electronics but people were setting up way before that

Last edited:

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Mans really think people were dancing and having a good time in cold ass NYC before the Jamaicains arrived?

aframs had the whole world dancing long before people knew what a jamaican was...even in NY

it seems like they discredited us (AA's). i dont know why french montana is in this.This video is some bullshyt, anyone who actually listened to the people who helped create hip hop will tell you the guy with the dreads is saying the same lie that west indians have been saying for years. They aren't hip hop heads, they are just got into once it got big, heard Herc was Jamaican, and just created a fake story that hasn't been challenged by most people unless you read.

Wear My Dawg's Hat

Superstar

D.ST.: "The Bronx Is The Home of Hip Hop"

Hoodoo Child

The Urban Legend

it started in the usa from a strand of southern afram culture

and then mixed with afram disco culture in various areas of NYC

na, the dj'ing part is from afram disco culture

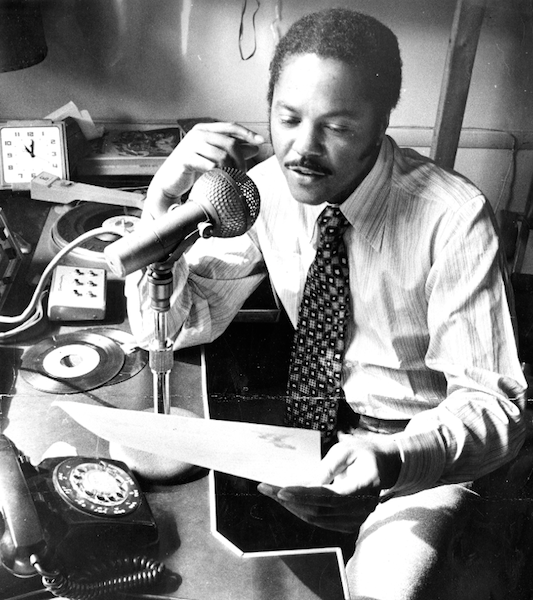

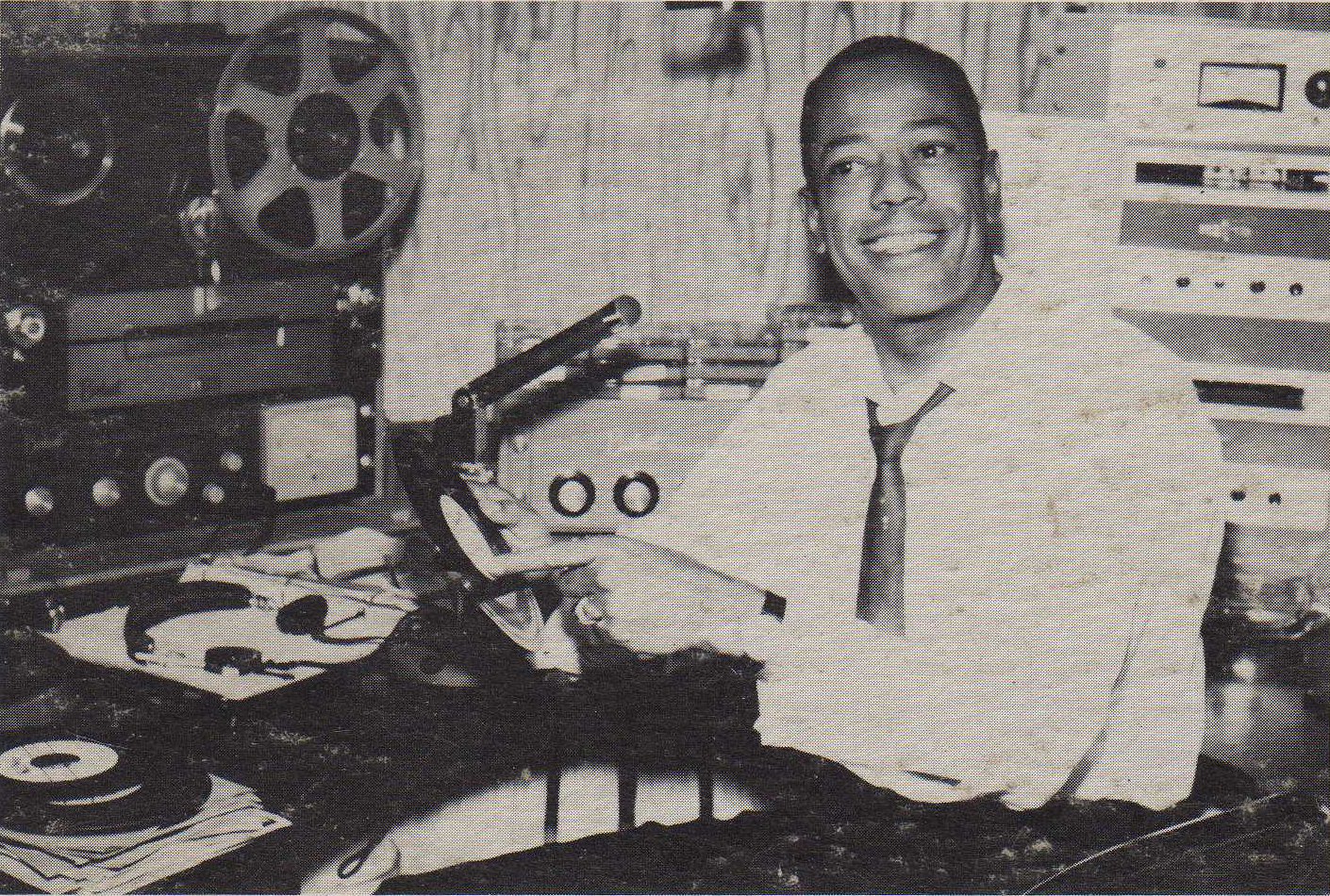

dj culture is jamaica is a direct result of them hearing afram radio dj's and the jukebox/dj's they saw in america when they came over to the usa

again,this was all inspired by their love for afram radio dj's

Grand opening

Grand closing

Grand closingComplex has young staff who doesn't really know hip hop before the 90's, and probably don't know who to go to, to find out the origins. The book "can't stop, won't stop" should have been read before doing that video, or even just listening to some Kool Herc youtube interviews. Being that most media in is NYC, and a lot of the people who get these jobs are of west indian or latin descent, they have no incentive to tell the truth, unless they are just honest people.it seems like they discredited us (AA's). i dont know why french montana is in this.

Complex, the guy with the dreads, and Dj Evil E, showed they know very little bout hip hop or black nyc culture before their eras. Doug E. Fresh knows, but they could have edited him to make it seem like something other then what he believes. At least with him, he showed how calypso effected his beat boxing techniques, so I have no issue with him in the video, but they are rewriting history with it.

Last edited: