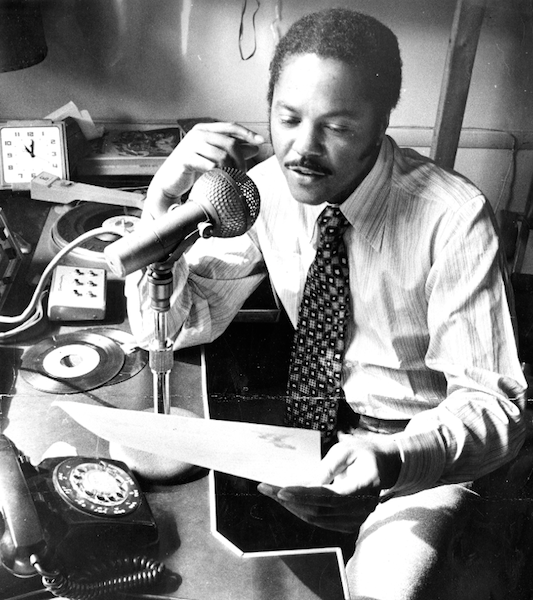

“The Jives of Dr. Hepcat” by KVET-AM DJ Albert Lavada Durst, published in 1953.

I was reading Beth Lesser’s amazing Rub-a-Dub Style: The Roots of Modern Dancehall, which is available for free download

here, and I found a quotation from Clive Chin that set me off on a wild goose chase through the roots of toasting. I have long had a fascination with the connection between toasting and hip hop and have written about that in this blog before, and presented on it at conference after I had the pleasure of interviewing DJ Kool Herc last year, but I hadn’t thoroughly ventured back to jive–until Beth Lesser.

Clive Chin, writes Lesser,

remembers toaster Count Matchuki carrying around a book. “There was one he said he bought out of Beverly’s [record shop] back in the ‘60s. The book was called Jives and it had sort of slangs, slurs in it and he was reading it, looking it over, and he found that it would be something that he could explore and study, so he took that book and it helped him.” Lesser writes that this book of jive may have been a boo, written in 1953, The Jives of Dr. Hepcat, which was published by Albert Lavada Durst, a DJ on KVET-AM in Austin, Texas. This version (read the entire copy

here) featured definitions for words and phrases commonly used by jive talking DJs like “threads,” which are clothes; “pad,” for house or apartment; “flip your lid,” for losing one’s balance mentally; and “chill,” to hold up or stop. Durst wrote in the introduction to his book, which sold for 50 cents, “In spinning a platter of some very popular band leader, I would come on something like this: ‘Jackson, here’s that man again, cool, calm, and a solid wig, he is laying a frantic scream that will strictly pad your skull, fall in and dig the happenings.’ Which is to say, the orchestra leader is a real classy singer and has a voice that most people would like. For instance, there was a jam session of topnotch musicians and everything was jumping and you would like to explain it to a hepster. These are the terms to use. ‘Gator take a knock down to those blow tops, who are upping some real crazy riffs and dropping them on a mellow kick and chappie the way they pull their lay hips our ship that they are from the land of razz ma tazz.’

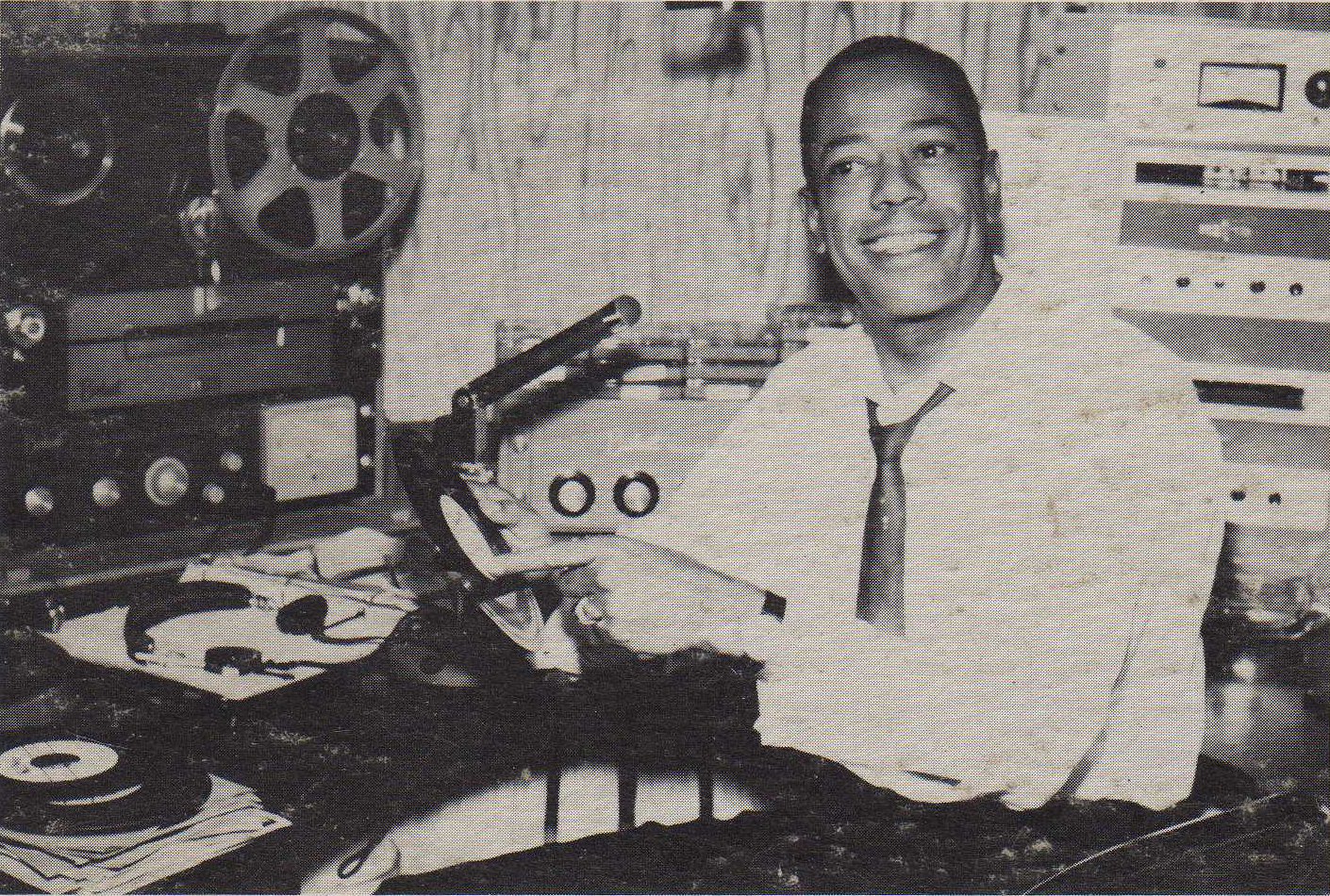

Cab Calloway’s “Hepsters Dictionary: Language of Jive,” 1944 version.

I decided to search further and found there was another popular book of jive written before Dr. Hepcat, although it is likely that Matchuki obtained Durst’s version given the era and the content. But Cab Calloway had his own publication of jive called “Cab Calloway’s Hepster Dictionary: Language of Jive” which was first published in 1939 and then revised to add more words in a 1944 printing. Calloway was the original emcee, the master of ceremonies, the hepcat, who understood jive and brought it to those who wanted to become part of this culture. As frequent band leader at the Cotton Club in front of Duke Ellington’s band during performances that were broadcast all over the continent, and as star in a number of feature films, Calloway brought the language of Harlem, jive, to audiences uneducated in the dialect of the black musicians. He established jive as a form of discourse.

Interior of Cab Calloway’s “Hepsters Dictionary”

Some of

the words in these dictionaries, and certainly the word “jive” itself, appear in the toasts of Count Matchuki, Lord Comic, and King Stitt. The style is similar as well, scatting over the music, punctuating the rhythm with verbal percussion, and boasting. Next week I will blog about the jive-talking American DJs like Vernon Winslow, Tommy Smalls, and Douglas Henderson, who influenced the Jamaican toasters since these similarities are fascinating as well.