What are you even talking about you still didn't explain where I was wrong, And there where organizations and movements way before nobel dru ali. Nobel Dru Ali and Garvey worked to gather as well. And there were pan-African conferences and groups before he set up his first temple he was still doing magic tricks. You saying we didn't have a strong organization or movement until the 20th century?first off the entire culture was set off by this man

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

If African Americans were allowed to keep their original African culture..

- Thread starter generic-username

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Field Marshall Bradley

Veteran

If Blacks kept African tradition, there would be bloodshed and revolution. There would be no America.

Why do you think we were converted to Christianity by force?

K.O.N.Y

Superstar

What are you even talking about you still didn't explain where I was wrong, And there where organizations and movements way before nobel dru ali. Nobel Dru Ali and Garvey worked to gather as well. And there were pan-African conferences and groups before he set up his first temple he was still doing magic tricks. You saying we didn't have a strong organization or movement until the 20th century?

No.

What im saying is the idea that most aafram orgs/movements being started by west indians is false

And offensive

Jean Jacket

NOPE

Educate the fool.

Oh I didn't mean it like that I was saying a lot of those organizations weren't soley African-American. And a lot of pan-african groups and conferences started in the west indies. And the isrealites started in the west indies. Rabbie Wentworth Arthur Matthew was west indian. But most the one west camps follow Aba Bivens who was AA I believe.No.

What im saying is the idea that most aafram orgs/movements being started by west indians is false

And offensive

K.O.N.Y

Superstar

i was under the impression that Ali predated all of themOh I didn't mean it like that I was saying a lot of those organizations weren't soley African-American. And a lot of pan-african groups and conferences started in the west indies. And the isrealites started in the west indies. Rabbie Wentworth Arthur Matthew was west indian. But most the one west camps follow Aba Bivens who was AA I believe.

@IllmaticDelta your services are needed breh

Nah and it was black organizations and movements before The Prophet Nobel Dru Ali. The first pan african conference was in the month of July the year 1900. And way before that you had folks like Bishop Henry Mcneal Turner who was the first leader to teach that god was black post slavery in america. And even way later you had Garvey who worked with the isrealites and the moors. Nobel Dru Ali and Garvey did some work together.i was under the impression that Ali predated all of them

@IllmaticDelta your services are needed breh

Premeditated

MANDE KANG

actually it kind of makes sense if you don't take it literallyThe NOI is a joke because the story of Yakub makes no sense to any sane person. The 5 percenters is just a ripoff of Islam and whatever else Clarence 13X imagined.

minus the c00n intention parts from Yakub

And that's actually Elijah's spin on Jacob from the bible. Who created the tribes of isreal.actually it kind of makes sense if you don't take it literally

minus the c00n intention parts from Yakub

Last edited:

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Oh I didn't mean it like that I was saying a lot of those organizations weren't soley African-American. And a lot of pan-african groups and conferences started in the west indies. And the isrealites started in the west indies. Rabbie Wentworth Arthur Matthew was west indian. But most the one west camps follow Aba Bivens who was AA I believe.

na...USA in the later 1800's

i was under the impression that Ali predated all of them

@IllmaticDelta your services are needed breh

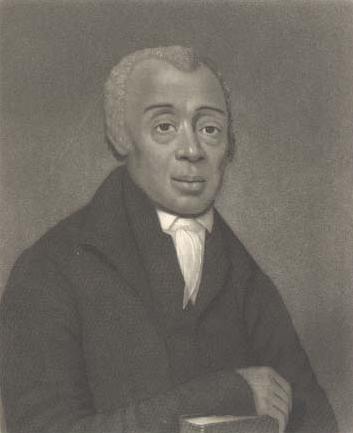

the father of the hebrew isrealites and who then paved the way for Moorish Science and similar groups is the afram below

When you combine religion with Black Nationalism/Afrocentrism you get stuff like..... (same way Rastafarianism was born in Jamaica)

William Saunders Crowdy (August 11, 1847 – August 4, 1908) was an American soldier, preacher, entrepreneur, theologian, and pastor. As one of the earliest Hebrew Israelites in the United States, he established the Church of God and Saints of Christ in 1896.

Black Judaism' has roots in Kansas

But did you know that "Black Judaism," as it's come to be known, has its roots right here in Kansas over a century ago? Or that it influenced such later religious developments as Rastafarianism and even the Nation of Islam?

It's true, according to numerous sources.

They point to the arrival of former slave and railroad cook William Saunders Crowdy in Lawrence, Kan., in 1896 and his establishment there of the Church of God and Saints of Christ as perhaps the watershed event in the movement that identifies African-Americans with the biblical Hebrews.

Within a couple of years, Crowdy had established satellite tabernacles all across Kansas, from Atchison to Topeka to Winfield. The COGASOC eventually withered away here, but it still exists. It has its headquarters in Virginia and is headed by one of Crowdy's descendants.

Saints of Christ?

Today, tens of thousands of people consider themselves Black Jews, even if the mainstream Jewish community doesn't completely accept them. At this point, the contentious issues are more theological than racial, and Rabbi Funnye has made it his business to bridge those gaps, according to an article in the July-August edition of Moment magazine titled "Post-Racial Rabbis."

Writer Jeremy Gillick says that Funnye is succeeding, to the extent that he has "been almost universally accepted as a rabbi by liberal Jewish movements, as well as by many more traditional groups."

That's apparently so in large part because the segment of Black Judaism to which Rabbi Funnye adheres has moved much closer to mainstream Judaism than others, including the COGASOC

It's doubtful that the rabbis of his day would have recognized William Crowdy as a peer, much less the prophet that COGASOC considers him today. There is that "Christ" business, although the COGASOC Web site has an explanation for that in its FAQ section:

"We interpret this name to mean that we are a religious organization which is directed by God, 'Church of God,' and we are followers of the anointed of God, 'Saints of Christ.' Our congregation should not be mistaken for Messianic Jews or Jews for Jesus, because we do not believe that Jesus is our Lord and Savior. ... We believe in the religion of Jesus and not the religion about Jesus."

Nonetheless, it continues, "We believe that Jesus was a prophet, and we accept all biblical prophets of God who taught the laws of God."

It is this sort of duality that led writers including James E. Landing in "Black Judaism," (Carolina Academic Press, 2002) and Yvonne Chireau in "Black Zion: African American Religious Encounters with Judaism," (Oxford University Press, 2000) to call COGASOC an admixture of Jewish and Christian theological concepts.

Still, congregants at Temple Beth El, the COGASAC headquarters in Belleville, Va., will celebrate Rosh Hashanah tonight, just as at every other synagogue and temple in the world. In fact, they observe most of the major holidays with the exception of Chanukah. The Festival of Lights, of course, is post-biblical, and COGSAC consider themselves biblical Jews.

And that gets to the heart of the split between the Black Jewish community and the normative one: Black Jews have their own interpretations of the Bible, and don't necessarily follow the rabbinic tradition.

Crowdy in Kansas

And while in the 19th century many black Christians found the biblical Israelites an inspiring allegory for their own enslavement, it was Crowdy who first popularized the literal identification of black Americans with Israelites, or Jews.

Born a slave in 1847 in Maryland, Crowdy served in the Union Army during the Civil War. After the war, he moved to Guthrie, Okla., and later to Kansas City, Mo., where he established a family and worked on the Santa Fe Railroad as a cook.

According to a history of COGASOC written by his daughter, it was William Crowdy's powerful singing voice that first attracted people to him. He was said to have arrived in Lawrence in 1896 and begun to sing and preach on the street. That led to a public meeting at the Douglas County Courthouse, attended by both whites and blacks, and to the incorporation of the COGASOC.

According to records reproduced by former University of Kansas student Elly Wynia in her book, "The Church of God and Saints of Christ: The Rise of Black Jews." (Routledge, 1994) COGASOC's "First General Annual Assembly Meeting" occurred in Lawrence on Oct. 10, 1899

During Crowdy's time in Lawrence, COGASOC records showed a "tabernacle" at 1239 New Jersey St., where a private home stands today. Henry Street, the location of the other Lawrence tabernacle, no longer exists today. Likewise, the address given for the Topeka tabernacle, 910 S.E. 12th St., is today merely the side yard of a rundown house in a historically black neighborhood.

If William Crowdy, the father of "Black Judaism," is still regarded a prophet in some circles, he's almost unknown in his old Kansas stomping grounds.

What are Black Jews?

Yvonne Chireau writes in "Black Zion" that "One of the first communities to which the designation 'black Jews' was applied was the Church of God and Saints of Christ (also known as the Temple Beth-el congregations), established in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1896 by William Saunders Crowdy. Crowdy, a former Baptist preacher, called his congregations 'tabernacles' and embedded select Jewish beliefs and practices within a format that was similar to that of a Christian church. The group's appropriation of Judaism constituted what for some writers have characterized as a Hebraic-Christian or Judeo-Christian formation, in which aspects of Old Testament tradition were integrated with Christian elements.... The Church of God adopted Jewish customs that may have been based on a literal interpretation of Old Testament rites.

"The Church of God, for instance, maintained the office of the rabbinate, celebrated Passover, and observed a Saturday Sabbath while incorporating new Testament principles, emphasizing the works of Jesus Christ and his teachings, and practicing such rituals as Baptism. This pattern of selecting components of Judaism and preserving theological and doctrinal perspectives from Christianity was typical of a number of groups in the early establishment of black Jewish communities in the United States."

'Black Judaism' has roots in Kansas

na...USA in the later 1800's

the father of the hebrew isrealites and who then paved the way for Moorish Science and similar groups is the afram below

When you combine religion with Black Nationalism/Afrocentrism you get stuff like..... (same way Rastafarianism was born in Jamaica)

William Saunders Crowdy (August 11, 1847 – August 4, 1908) was an American soldier, preacher, entrepreneur, theologian, and pastor. As one of the earliest Hebrew Israelites in the United States, he established the Church of God and Saints of Christ in 1896.

Black Judaism' has roots in Kansas

'Black Judaism' has roots in Kansas

Are you proud of that c00n hebrew shyt, son?

Didn't Richard Allen and Bishop Henry Mcneal Turner come before though?na...USA in the later 1800's

the father of the hebrew isrealites and who then paved the way for Moorish Science and similar groups is the afram below

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Would groups like Nation Of Islam, Hebrew Israelites, 5 percenters, etc etc exist?

yes because the main reason those things formed was because of white racism combined with afrocentric/black nationalist views. Jim Crow/white racism was going to be around regardless.

yes because the main reason those things formed was because of white racism combined with afrocentric/black nationalist views. Jim Crow/white racism was going to be around regardless.

It would be a more militant version of Orixa stuff.