yup...many of the early virginia, angolan slaves had Portuguese sounding names. This is where the fake Portuguese origin of the Melungeons comes from

This article that I am posting is actually not entirely true, because there were Africans already in the Americas since 1400 and 1500's. However, I assume that the writer meant slaves from Africa; which is different than the indentured servants (like John Punch) that had been bought to the USA before these people.

Virginia's First Africans

Virginia's first Africans arrived at Point Comfort, on the James River, late in August 1619. There, "20. and odd Negroes" from the English ship White Lion were sold in exchange for food and some were transported to Jamestown, where they were sold again, likely into slavery. Historians have long believed these Africans to have come to Virginia from the Caribbean, but Spanish records suggest they had been captured in a Spanish-controlled area of West Central Africa. They probably were Kimbundu-speaking people, and many of them may have had at least some knowledge of Catholicism. While aboard the São João Bautista bound for Mexico, they were stolen by the White Lion and another English ship, the Treasurer. Once in Virginia, they were dispersed throughout the colony. The number of Virginia's Africans increased to thirty-two by 1620, but then dropped sharply by 1624, likely because of the effects of disease and the Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622–1632). Evidence suggests that many were baptized and took Christian names, and some, likeAnthony and Mary Johnson, won their freedom and bought land. By 1628, after a shipload of about 100 Angolans was sold in Virginia, the Africans' population jumped dramatically.

Africans, Virginia's First

When you click on the article and read in greater detail of the Origins this is what it states:

Origins

The discovery by the historian Engel Sluiter of Spanish records linking the slaves sold in Virginia to the attack on the

São João Bautista discredits earlier theories that the Africans had been not been brought directly to the Chesapeake from Africa. Instead, following the research of John K. Thornton, Virginia's first Africans may have been enslaved either in Kongo, south of the mouth of the Congo (or Zaire) River, or in region just to the south. This is where Portuguese (and by 1618–1619 under Spanish rule) authorities were taking advantage of the disturbed politics in an Mbundu region in the watershed of the Kwanza River. Most likely they were captured from the forces of the nearby Ndongo polity, where in 1618 and 1619 the governor of Angola, Luis Mendes de Vasconçelos, fighting alongside a ruthless African mercenary group called the Imbangala, led two campaigns against the Kimbundu-speaking people of the region. Thousands were captured and likely provided the cargoes for six Portuguese slave ships from Angola that arrived in Vera Cruz between June 18, 1619, and June 21, 1620.

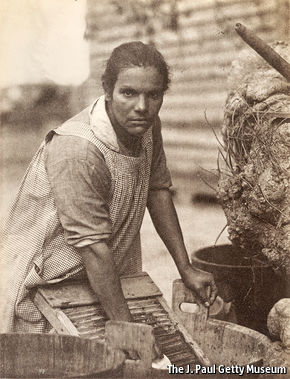

The Ndongo people lived largely in rural areas where they raised crops such as millet and sorghum and tended cattle. There was one densely populated political center, the city of Angoleme, which in 1564 seems to have had 20,000 to 30,000 residents living in 5,000 to 6,000 thatched houses. These people may have had come contact with Jesuit missionaries, and the Portuguese required that slaves be baptized before they arrived in America, a pro forma gesture that did not necessarily result in the Africans bringing with them Christian practices.

In the decades that followed, most slaves arriving in Virginia through the slave trade were captured not by Europeans but by other Africans who sold them to the Europeans at markets. As a result, slaves suffering through the

Middle Passage often hailed from different regions and villages, spoke different languages, and abided by different social, political, and religious customs. The Ndongo, by contrast, were captured more directly by the Portuguese and shared with one another a complex ethnic identity.

Some historians have argued that these first Africans may have been Christian, although it is unlikely that they were. A Virginia law, passed in 1670, defined as slaves-for-life all non-Christian

servants brought to the colony "by shipping." Such servants were, almost without exception, Africans, suggesting an assumption on the part of lawmakers that Africans were, by definition, non-Christians. The law already precluded freedom through conversion, and in 1682 it expanded its description of slaves-for-life to include all non-Christian servants (in other words,

Virginia Indians who were imported into the colony, in addition to Africans).

...

Some of the twenty-one Africans listed in the 1624 muster had European names, suggesting that they had been baptized. This could have occurred prior to their leaving Africa or after they reached Virginia... .

smiley because those africans were already practicing non-native, african religion(s) before they even got to the Americas since some were making a big deal about them being Christianized like Islamicized is any different or better

smiley because those africans were already practicing non-native, african religion(s) before they even got to the Americas since some were making a big deal about them being Christianized like Islamicized is any different or better Just gonna see myself out not gonna try to make anymore enemies no beef.

Just gonna see myself out not gonna try to make anymore enemies no beef.