IllmaticDelta

Veteran

@IllmaticDelta isn't there a link between fife and drum and current day marching bands?

I wouldn't say directly but fife and drum from mississippi has the same spirit/groove that you get in new orleans and hbcu bands.

@IllmaticDelta isn't there a link between fife and drum and current day marching bands?

Maybe not as elaborate as what you see in New Orleans, but still being practiced in the present, nonetheless.

@IllmaticDelta isn't there a link between fife and drum and current day marching bands?

The Gullah geechee people are perceived to be one of the most "African" people not only amongst Aframs but new world blacks as a whole

That's why you have certain black foreigners who try to use them to say that they retained their "roots" compared to modern Aframs which is a whole other debatable subject

Where are the young peoples? As unique and and important as the culture is, it has to be passed on to the little ones

Ehh you asked for present day examples, not how strong the culture still is.

And btw, on that subject I absolutely agree with you and I love how yall keep it going no matter what. I kind of have a theory on why a place like NOLA is still holding a lot stronger than smaller rural locations when it comes to stuff like this, but I’m still working that out.

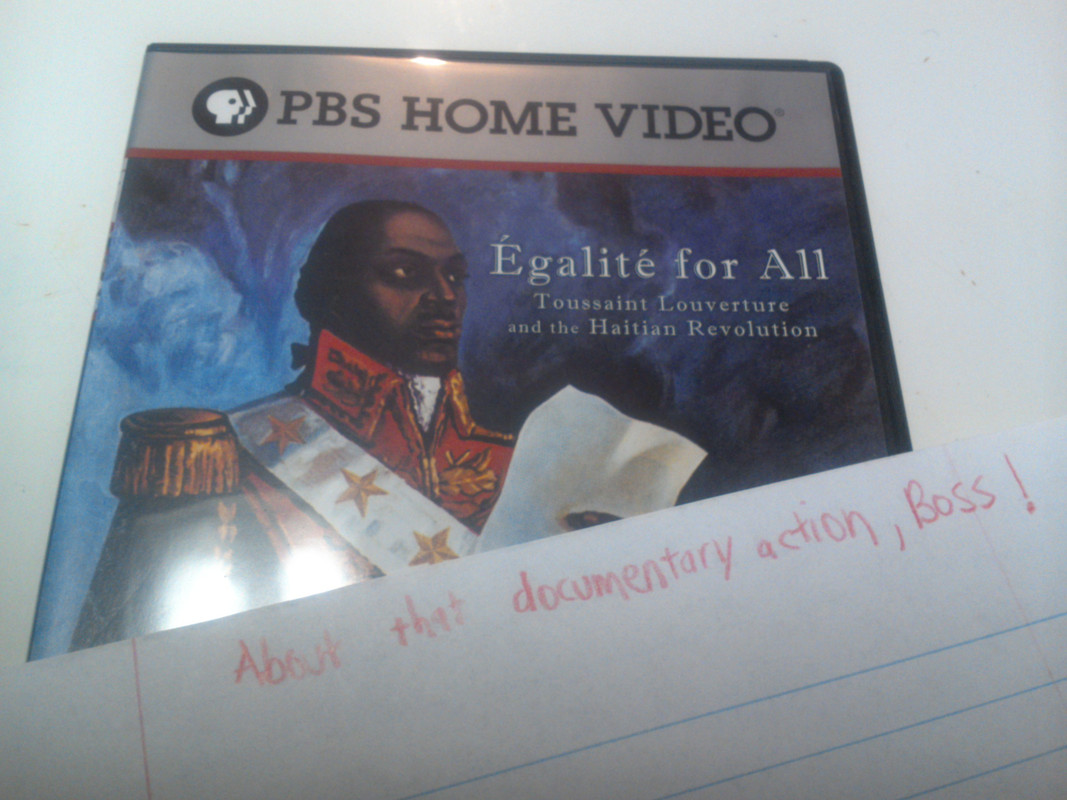

AAME : image

not sure if this has been posted in this thread or not, but it does show evidence of a strong Hatian influence in LouisianaIn January 1804, an event of enormous importance shook the world of the enslaved and their owners. The black revolutionaries, who had been fighting for a dozen years, crushed Napoleon's 60,000 men-army - which counted mercenaries from all over Europe - and proclaimed the nation of Haiti (the original Indian name of the island), the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere and the world's first black-led republic. The impact of this victory of unarmed slaves against their oppressors was felt throughout the slave societies. In Louisiana, it sparked a confrontation at Bayou La Fourche. According to white residents, twelve Haitians from a passing vessel threatened them "with many insulting and menacing expressions" and "spoke of eating human flesh and in general demonstrated great Savageness of character, boasting of what they had seen and done in the horrors of St. Domingo [Saint Domingue]."

The slaveholders' anxieties increased and inspired a new series of statutes to isolate Louisiana from the spread of revolution. The ban on West Indian bondspeople continued and in June 1806 the territorial legislature barred the entry from the French Caribbean of free black males over the age of fourteen. A year later, the prohibition was extended: all free black adult males were excluded, regardless of their nationality. Severe punishments, including enslavement, accompanied the new laws.

However, American efforts to prevent the entry of Haitian immigrants proved even less successful than those of the French and the Spanish. Indeed, the number of immigrants skyrocketed between May 1809 and June 1810, when Spanish authorities expelled thousands of Haitians from Cuba, where they had taken refuge several years earlier. In the wake of this action, New Orleans' Creole whites overcame their chronic fears and clamored for the entry of the white refugees and their slaves. Their objective was to strengthen Louisiana's declining French-speaking community and offset Anglo-American influence. The white Creoles felt that the increasing American presence posed a greater threat to their interests than a potentially dangerous class of enslaved West Indians.

American officials bowed to their pressure and reluctantly allowed white émigrés to enter the city with their slaves. At the same time, however, they attempted to halt the migration of free black refugees. Louisiana's territorial governor, William C. C. Claiborne, firmly enforced the ban on free black males. He advised the American consul in Santiago de Cuba:

Males above the age of fifteen, have . . . been ordered to depart. - I must request you, Sir, to make known this circumstance and also to discourage free people of colour of every description from emigrating to the Territory of Orleans; We have already a much greater proportion of that population than comports with the general Interest.

Brehs were pawgin

Claiborne and other officials labored in vain; the population of Afro-Creoles grew larger and even more assertive after the entry of the Haitian émigrés from Cuba, nearly 90 percent of whom settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population. Sixty-three percent of Crescent City inhabitants were now black. Among the nation's major cities only Charleston, with a 53 percent black majority, was comparable.

The multiracial refugee population settled in the French Quarter and the neighboring Faubourg Marigny district, and revitalized Creole culture and institutions. New Orleans acquired a reputation as the nation's "Creole Capital."

The rapid growth of the city's population of free persons of color strengthened the "three-caste" society - white, mixed, black - that had developed during the years of French and Spanish rule. This was quite different from the racial order prevailing in the rest of the United States, where attempts were made to confine all persons of African descent to a separate and inferior racial caste - a situation brought about by political reality in the South that promoted white unity across class lines and the immersion of all blacks into a single and subservient social caste.

In Louisiana, as lawmakers moved to suppress manumission and undermine the free black presence, the refugees dealt a serious blow to their efforts. In 1810 the city's French-speaking Creoles of African descent, reinforced by thousands of Haitian refugees, formed the basis for the emergence of one of the most advanced black communities in North America.

Ehh you asked for present day examples, not how strong the culture still is.

And btw, on that subject I absolutely agree with you and I love how yall keep it going no matter what. I kind of have a theory on why a place like NOLA is still holding a lot stronger than smaller rural locations when it comes to stuff like this, but I’m still working that out.

more

The second migratory path followed by the runaways contrasted sharply with the urban migration. It led into the most remote, isolated backcountry, dense forests, bayous, swamps, or Indian territories. There, the fugitives formed maroon communities - organized enclaves of runaways-that developed in the earliest days and continued through abolition. As early as 1690, farmers in Harlem, New York, were complaining about the inhabitants of a maroon colony who were attacking the settlers.

The first known free black community in North America was a settlement of fugitive Africans called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose. Located near St. Augustine in Spanish Florida, it operated from 1739 to 1763.

Some runaways established camps in Elliott's Cut, between the Ashepoo and Pon Pon rivers in South Carolina; and in the Indian nations of Alabama and Mississippi. In the eighteenth century, others had taken refuge in Spanish Florida with the Seminole Indians. Black and native Seminoles joined forces against the U.S. army during two wars in 1812 and 1835. In 1822, the sub-agent for the Florida Indians wrote:

It will be difficult (says he) to form a prudent determination with respect to the ‘maroon negroes' (Exiles), who live among the Indians . . . . They fear being again made slaves, under the American Government, and will omit nothing to increase or keep alive mistrust among the Indians, whom they in fact govern. If it should become necessary to use force with them, it is to be feared that the Indians will take their part. It will, however, be necessary to remove from the Floridas this group of freebooters, among whom runaway Negroes will always find a refuge. It will, perhaps, be possible to have them received at St. Domingo, or to furnish them means of withdrawing from the United States

AAME : Home

During the century of the domestic trade, roughly equal numbers of males and females were sold away. The exception was the Louisiana sugar plantations, whose population made up some 6 percent of the nation’s enslaved. Importation to New Orleans, where many sugar planters bought their enslaved workers, was about 58 percent male, and traders sent very few young children to that market. The exhausting labor in the cane fields took an exceptionally heavy toll on the laborers’ health, and the demands of the sugar planters meant that the southern Louisiana market tended to import particularly strong workers.

those are the gullah/sea islanders

North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida: Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor (U.S. National Park Service)

it ain't only the light skinned creoles either.

it ain't only the light skinned creoles either. views towards "mainstream" African Americans

views towards "mainstream" African AmericansI've noticed over the years a lot of New Orleans nikkas be on someit ain't only the light skinned creoles either.

We know it was Jean Claude instead of Johnny Lee nikka but they still cacs and you still a nikka.

Even seen some Gullah nikkas shareviews towards "mainstream" African Americans

mentality in mass after Katrina.

mentality in mass after Katrina.Riverwalk Jazz - Stanford University LibrariesThe boogie woogie beat poured out of the piney woods of Texas over to the Gulf Coast and New Orleans, then on up to Chicago. But no one yet called it boogie woogie. Depending on where it was being played, the distinctive boogie woogie blues sound was called Fast Texas Piano, New Orleans Hop Scop, the Rocks, the Fives or the Sixteens.

Jelly Roll Morton recalled early masters of boogie woogie with names like Stavin’ Chain, Skinny Head Pete, Papa Lord God, the Toothpick or Porkchops. A piano player from Houston, Texas, with the patriotic moniker George Washington Thomas Jr., is regarded as the first to publish sheet music of a twelve bar blues progression written with a boogie woogie bass line. Thomas wrote his ‘Hop Scop Blues’ in 1911, and published it in New Orleans in 1916. On this broadcast, John Sheridan and The Jim Cullum Jazz Band play Thomas’ rarely heard piece, "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues."

In February 1923, George W. Thomas Jr. (as Clay Custer) made what is widely considered the first boogie woogie-inflected recording with his piano composition "The Rocks" composed with his younger brother Hersal. The eldest son of a Baptist preacher George W. Thomas Jr. became the patriarch of a Texas blues clan —standouts in the family include his brother Hersal (a boogie woogie child prodigy) and his sister Sippie Wallace, famous for her long and illustrious career as a blues singer.

they would rather attribute cultural aspects like that to Europeans, Native Americans, Caribbeans, a direct African connection, or anything but the AADOS from which it actually came to make themselves seem exotic.

they would rather attribute cultural aspects like that to Europeans, Native Americans, Caribbeans, a direct African connection, or anything but the AADOS from which it actually came to make themselves seem exotic.Texas ZydecoTo most people, zydeco appears as quintessentially Louisiana as gumbo. Certainly, the music originated among black Creoles of southwest Louisiana. But the swamps of southwest Louisiana spill across the Sabine River into southeast Texas, and the music originally known as "la-la" quickly trickled west, too. There it fused with blues to create a new sound that came to be known, spelled, and recorded as "zydeco."Black Creoles from Louisiana began moving into southeast Texas in search of better jobs during the first half of the twentieth century. As they resettled, so did their music. Texas Zydeco describes how many of the most formative players and moments in modern zydeco history developed in Texas, especially Houston.

As the new players traveled back and forth between Houston and Lafayette, Louisiana, they spread the new sound along a "zydeco corridor" that is the musical axis around which zydeco revolves to this day. Roger Wood and James Fraher spent years traveling this corridor, interviewing and photographing hundreds of authentic musicians, dancers, club owners, and fans. As their words and images make clear, zydeco, both historically and today belongs not to a state but to all the people of the upper Gulf Coast.

Award Winning Documentary based on Dr. Roger Wood and James Fraher's book. Directed and edited by Rubén Durán, Michael Brims, and Donna Pinnick.