I disagree with this as well, more and more people are becoming financially aware partially due to conspiracy theorists such as clickbait articles and YouTube videos etc. Most people don’t believe the “Rothchilds control the world” conspiracies but they have an innate understanding that wealth is concentrated in a small population and the wealthy conspire to keep their wealth through nefarious means such as market manipulation lobbying etc. People see how CEOs run companies into the ground yet get bailout with tax payer money and get their bonuses. Companies get bailed out with tax payer funds and layoff thousands, ship the jobs overseas and do stock buy backs. There’s no conspiracy in that. Now we have cryptocurrency which will replace the dollar and more and more people are learning about it everyday.Explanations for debt, recessions, bailout, etc. are pretty simple without needing any sort of conspiracy theory. I've repeatedly posted the predictions of Silvio Gesell on here, who noted the fundamental issues with our interest-based economy before the Federal Reserve was even created.

And your numbers are way off. Over $400 billion was given to Americans in direct cash payments. Even more was given directly to Americans via unemployment increases and PPP loans. Not that it's really relevant - it's easy to see how rich people have always gamed the system to increase the wealth disparity. But you can see that through the open, obvious shyt that's down every day.

I'm convinced that the rich people who run Wall Street and government enjoy it when these conspiracy theories are spread, because it keeps people focused chasing ghosts rather than trying to change the actual system operating right before their eyes.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

4 Presidents-WTF?!! Why Ya’ll Ain’t Tell Me?!

- Thread starter ⠝⠕⠏⠑

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?No, America didn't "literally get involved", it was a NATO intervention. Just the same as when we sent forces into Serbia and got Milosevic out of the cut. It was initiated by Sarkozy in France first, not America.All of the examples such as Afghanistan and Iraq the United States had some type of economic/American interest in or previous interaction to warrant the intervention. I’m not going to go through each example one by one but take Grenada for instance, we had Americans living on the island and they also didn’t want communism spreading throughout the rest of the carribean. Libya had a civil war and America literally got involved and had ghadaffi directly killed almost overnight. Even Obama said his greatest regret was how he handled Libya.

Between 13 and 16 January 2011, upset at delays in the building of housing units and over political corruption, protesters in Bayda, Derna, Benghazi and other cities broke into, and occupied, housing that the government had been building. Protesters also clashed with police in Bayda and attacked government offices.[130][131] By 27 January, the government had responded to the housing unrest with an over €20 billion investment fund to provide housing and development.

In late January, Jamal al-Hajji, a writer, political commentator and accountant, "call[ed] on the Internet for demonstrations to be held in support of greater freedoms in Libya" inspired by the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. He was arrested on 1 February by plain-clothes police officers, and charged on 3 February with injuring someone with his car. Amnesty International stated that because al-Hajji had previously been imprisoned for his non-violent political opinions, the real reason for the present arrest appeared to be his call for demonstrations.[134] In early February, Gaddafi, on behalf of the Jamahiriya, met with political activists, journalists and media figures and warned them that they would be held responsible if they disturbed the peace or created chaos in Libya.[135]

The protests would lead to an uprising and civil war, as part of the wider Arab Spring,[136][137] which had already resulted in the ousting of long-term presidents of adjacent Tunisia and Egypt.[138] Social media played a central role in organizing the opposition.[139][140][141][142][143] A social media website declared an alternative government, one that would be an interim national council, was the first to compete with Muammar Gaddafi's political authority. Gaddafi's senior advisor attempted to reject the idea by tweeting his resignation.[144]

Uprising and civil war[edit]

The protests, unrest and confrontations began in earnest on 2 February 2011. They were soon nicknamed the Libyan Revolution of Dignity by the protesters and foreign media.[145] Foreign workers and disgruntled minorities protested in the main square of Zawiya, Libya against the local administration. This was succeeded by race riots, which were squashed by the police and pro-Gaddafi loyalists. On the evening of 15 February, between 500 and 600 demonstrators protested in front of Benghazi's police headquarters after the arrest of human rights lawyer Fathi Terbil. Crowds were armed with petrol bombs and threw stones. Marchers hurled Molotov cocktails in a downtown square in Benghazi, damaging cars, blocking roads, and hurling rocks. Police responded to crowds with tear gas, water cannon, and rubber bullets.[146] 38 people were injured, including 10 security personnel.[147][148] The novelist Idris Al-Mesmari was arrested hours after giving an interview with Al Jazeera about the police reaction to protests.[147]

In a statement released after clashes in Benghazi, a Libyan official warned that the Government "will not allow a group of people to move around at night and play with the security of Libya". The statement added: "The clashes last night were between small groups of people – up to 150. Some outsiders infiltrated that group. They were trying to corrupt the local legal process which has long been in place. We will not permit that at all, and we call on Libyans to voice their issues through existing channels, even if it is to call for the downfall of the government."[149]

On the night of 16th of February in Beyida, Zawiya and Zintan, hundreds of protesters in each town calling for an end to the Gaddafi government set fire to police and security buildings.[147][150]

A "Day of Rage" in Libya and by Libyans in exile was planned for 17 February.[135][151][152] The National Conference for the Libyan Opposition asked that all groups opposed to the Gaddafi government protest on 17 February in memory of demonstrations in Benghazi five years earlier.[135] The plans to protest were inspired by the Tunisian and Egyptian revolution.[135] Protests took place in Benghazi, Ajdabiya, Derna, Zintan, and Bayda. Libyan security forces fired live ammunition into the armed protests. Protesters torched a number of government buildings, including a police station.[153][154] In Tripoli, television and public radio stations had been sacked, and protesters set fire to security buildings, Revolutionary Committee offices, the interior ministry building, and the People's Hall.[155][156]

On 18 February, police and army personnel later withdrew from Benghazi after being overwhelmed by protesters. Some army personnel also joined the protesters; they then seized the local radio station. In Bayda, unconfirmed reports indicated that the local police force and riot-control units had joined the protesters.[157] On 19 February, witnesses in Libya reported helicopters firing into crowds of anti-government protesters[158] a claim that Amnesty International stated they found no evidence for, noting that protesters repeatedly made verifiably false claims about repression by the government.[147][150] The army withdrew from the city of Bayda.

Amnesty International also reported that security forces targeted paramedics helping injured protesters.[194] In multiple incidents, Gaddafi's forces were documented using ambulances in their attacks.[195][196] Injured demonstrators were sometimes denied access to hospitals and ambulance transport. The government also banned giving blood transfusions to people who had taken part in the demonstrations.[197] Security forces, including members of Gaddafi's Revolutionary Committees, stormed hospitals and removed the dead. Injured protesters were either summarily executed or had their oxygen masks, IV drips, and wires connected to the monitors removed. The dead and injured were piled into vehicles and taken away, possibly for cremation.[198][199] Doctors were prevented from documenting the numbers of dead and wounded, but an orderly in a Tripoli hospital morgue estimated to the BBC that 600–700 protesters were killed in Green Square in Tripoli on 20 February. The orderly said that ambulances brought in three or four corpses at a time, and that after the ice lockers were filled to capacity, bodies were placed on stretchers or the floor, and that "it was in the same at the other hospitals".[198]

In the eastern city of Bayda, anti-government forces hanged two policemen who were involved in trying to disperse demonstrations. In downtown Benghazi, anti-government forces killed the managing director of al-Galaa hospital. The victim's body showed signs of torture.[200]

On 19 February, several days after the conflict began, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi announced the creation of a commission of inquiry into the violence, chaired by a Libyan judge, as reported on state television. He stated that the commission was intended to be "for members of Libyan and foreign organizations of human rights" and that it will "investigate the circumstances and events that have caused many victims."[156]

First Libyan Civil War - Wikipedia

- 21 February 2011: Libyan deputy Permanent Representative to the UN Ibrahim Dabbashi called "on the UN to impose a no-fly zone on all of Tripoli to cut off all supplies of arms and mercenaries to the regime."[42]

- 23 February 2011: French President Nicolas Sarkozy pushed for the European Union (EU) to pass sanctions against Gaddafi (freezing Gaddafi family funds abroad) and demand he stop attacks against civilians.

- 25 February 2011: Sarkozy said Gaddafi "must go."[57]

- 26 February 2011: United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 was passed unanimously, referring the Libyan government to the International Criminal Court for gross human rights violations. It imposed an arms embargo on the country and a travel ban and assets freeze on the family of Muammar Al-Gaddafi and certain Government officials.[58]

- 28 February 2011: British Prime Minister David Cameron proposed the idea of a no-fly zone to prevent Gaddafi from "airlifting mercenaries" and "using his military aeroplanes and armoured helicopters against civilians."[47]

- 1 March 2011: The US Senate unanimously passed non-binding Senate resolution S.RES.85 urging the United Nations Security Council to impose a Libyan no-fly zone and encouraging Gaddafi to step down. The US had naval forces positioned off the coast of Libya, as well as forces already in the region, including the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise.[59]

- 2 March 2011: The Governor General of Canada-in-Council authorised, on the advice of Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper, the deployment of the Royal Canadian Navy frigate HMCS Charlottetown to the Mediterranean, off the coast of Libya.[60] Canadian National Defence Minister Peter MacKay stated that "[w]e are there for all inevitabilities. And NATO is looking at this as well ... This is taken as a precautionary and staged measure."[59]

- 7 March 2011: US Ambassador to NATO Ivo Daalder announced that NATO decided to step up surveillance missions of E-3 AWACS aircraft to twenty-four hours a day. On the same day, it was reported that an anonymous UN diplomat confirmed to Agence France Presse that France and Britain were drawing up a resolution on the no-fly zone that would be considered by the UN Security Council during the same week.[46] The Gulf Cooperation Council also on that day called upon the UN Security Council to "take all necessary measures to protect civilians, including enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya."

- 9 March 2011: The head of the Libyan National Transitional Council, Mustafa Abdul Jalil, "pleaded for the international community to move quickly to impose a no-fly zone over Libya, declaring that any delay would result in more casualties."[43] Three days later, he stated that if pro-Gaddafi forces reached Benghazi, then they would kill "half a million" people. He stated, "If there is no no-fly zone imposed on Gaddafi's regime, and his ships are not checked, we will have a catastrophe in Libya."[44]

- 10 March 2011: France recognized the Libyan NTC as the legitimate government of Libya soon after Sarkozy met with them in Paris. This meeting was arranged by Bernard-Henri Lévy.[61]

- 12 March 2011: The Arab League "called on the United Nations Security Council to impose a no-fly zone over Libya in a bid to protect civilians from air attack."[51][52][53][62] The Arab League's request was announced by Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi bin Abdullah, who stated that all member states present at the meeting agreed with the proposal.[51] On 12 March, thousands of Libyan women marched in the streets of the rebel-held town of Benghazi, calling for the imposition of a no-fly zone over Libya.[45]

- 14 March 2011: In Paris at the Élysée Palace, before the summit with the G8 Minister for Foreign Affairs, Sarkozy, who is also the president of the G8, along with French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé met with US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and pressed her to push for intervention in Libya.[63]

- 15 March 2011: A resolution for a no-fly zone was proposed by Nawaf Salam, Lebanon's Ambassador to the UN. The resolution was immediately backed by France and the United Kingdom.[64]

- 17 March 2011: The UN Security Council, acting under the authority of Chapter VII of the UN Charter, approved a no-fly zone by a vote of ten in favour, zero against, and five abstentions, via United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973. The five abstentions were: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and Germany.[54][55][56][65][66] Less than twenty-four hours later, Libya announced that it would halt all military operations in response to the UN Security Council resolution.[67][68]

- 18 March 2011: The Libyan foreign minister, Moussa Koussa, said that he had declared a ceasefire, attributing the UN resolution.[69] However, artillery shelling on Misrata and Ajdabiya continued, and government soldiers continued approaching Benghazi.[21][70] Government troops and tanks entered the city on 19 March.[71] Artillery and mortars were also fired into the city.[72]

- 18 March 2011: U.S. President Barack Obama orders military air strikes against Muammar Gaddafi's forces in Libya in his address to the nation from the White House.[73] US President Obama later held a meeting with eighteen senior lawmakers at the White House on the afternoon of 18 March[74]

- 19 March 2011: French[75] forces began the military intervention in Libya, later joined by coalition forces with strikes against armoured units south of Benghazi and attacks on Libyan air-defence systems, as UN Security Council Resolution 1973 called for using "all necessary means" to protect civilians and civilian-populated areas from attack, imposed a no-fly zone, and called for an immediate and with-standing cease-fire, while also strengthening travel bans on members of the regime, arms embargoes, and asset freezes.[20]

- 21 March 2011: Obama sent a letter to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate.[76]

- 24 March 2011: In telephone negotiations, French foreign minister Alain Juppé agreed to let NATO take over all military operations on 29 March at the latest, allowing Turkey to veto strikes on Gaddafi ground forces from that point forward.[77] Later reports stated that NATO would take over enforcement of the no-fly zone and the arms embargo, but discussions were still under way about whether NATO would take over the protection of civilians mission. Turkey reportedly wanted the power to veto airstrikes, while France wanted to prevent Turkey from having such a veto.[78][79]

- 25 March 2011: NATO Allied Joint Force Command in Naples took command of the no-fly zone over Libya and combined it with the ongoing arms embargo operation under the name Operation Unified Protector.[80]

I'm not saying I support that shyt, but it's not unusual. It's right in line with hundreds of shytty foreign policy moves we've made over time.

Last edited:

I recently watched a documentary with a friend of mine. It’s on Amazon Prime and it’s called “4 Presidents.”

Edit: Here’s the link 4 Presidents (2020) - IMDb

So this documentary tells the story of how there is one MAJOR connection between the assassinations of Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley and Kennedy.

So here’s the shyt I learned that had me going

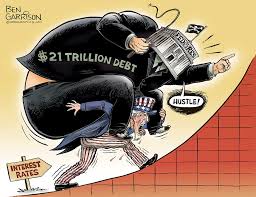

1.) The U.S. Treasury is completely different from the Federal Reserve.

I’m sure I learned this shyt in middle school social studies class but

Ain’t nobody paying attention to that shyt day today and why is it even important?!

2.) Well, it’s important because the rich asses that own the Federal Reserve are private bankers who don’t work for the government.

These evil geniuses print money and give it to the U.S. and we gotta pay it back...with BIG ASS INTEREST.

Sounds fukked up, right?!!Well has anybody ever tried to DO something about it?

YEP....and all of em got taken the hell out.

Fukking crazy! Every American president who went up against the Federal Reserve got shot.

Who the FUKK ARE THESE PEOPLE?!!!

Former Hedge Fund Portfolio Manager.

1) Federal reserve is not owned by anyone!

The federal reserve has board members of different banks which are true, but they are not owned by anyone. Banks receive money from the federal banks at low-interest rates and are suppose to lend out to people or institutions.

2)

A lot of what you wrote is incomplete and wayyyyy more nuanced than that. It's called federal fractional centralized banking. It is the current model and model that we use in capitalism. And it's the only way we have been able to grow at a fast past the only reason why your typing on that fancy phone or computer connected to the Internet. The creation of surplus credit and debt at a fast pace. Excess capital is created so it can be loaned out but the flip side of that is sometimes too much capital is created and bad loans happen and you get 08 in America or Japan in the 1980 -1990s.

There is no grand conspiracy to steal money from people. The masses have never had money or wealth to steal from period! To be honest no other time in history has capital been so cheap and plentiful.

3) The purpose of the federal reserve is to be the lender of last resort! You dont want to be around a place that has bank runs. Banks dont have to keep all deposits on hand and since they dont have to do that there needs to be a lender of the last resorts. The exact reason why the gold standard has failed and will fail again. Bank runs! To save the economy when instability arises.

4) To answer the other silliest being typed in this thread. The federal has destroyed the dollar yes and no!

The American dollar is the reserve currency. Just like anything else in the world the more of something there is the less value it holds. America has to print dollars for other countries to use as a medium of exchange.

The dollar is the world's medium of exchange.

The only thing the fed is guilty of is incompetence and it's not entirely their fault they are using an outdated framework to analyze and solve problems.

Picture capitalism like an iPhone, the phone is the hardware which is like banks, businesses etc. but new businesses arise and create different problems so a software update is needed another OS to solve the problem. The Fed is using an old iPhone and old OS it doesn't work in this climate. All countries with central banks are facing this problem. So it's not their fault entirely. This is why we removed older standards, ie the gold standard or why we have new problems like zero-interest bonds.

5) if you're looking for a conspiracy-lite, it would be the BIS.( Bank of International Settlements) The central banks of all central banks. Can't recall ever seeing a direct list of all its 60 bank members and showing how they interact and the deals they arrange. But those are sovereign nations so some level of secrets needs to happen.

6) Dont take anyone's word here as information do your research! These explanations are as laymen as I can get without writing essays.

Last edited:

“28 March 2011: Obama addressed the American people on the rational for U.S. military intervention with NATO forces in Libya at the National Defense University.“No, America didn't "literally get involved", it was a NATO intervention. Just the same as when we sent into Serbia and got Milosevic out of the cut. It was initiated by Sarkozy in France first, not America.

I'm not saying I support that shyt, but it's not unusual. It's right in line with hundreds of shytty foreign policy moves we've made over time.

Yes, we were there in support of NATO. You made it sound like we independently intervened in Libya's Civil War. How was it different than when we went after Milosevic as part of NATO in Serbia?“28 March 2011: Obama addressed the American people on the rational for U.S. military intervention with NATO forces in Libya at the National Defense University.“

I'm referring to the theory that secret shadowy people are running the Fed or that they're knocking off US Presidents to maintain their power.What conspiracy theory are you referring to? And that’s the whole point of my post, you don’t have to believe in any conspiracy theory when you have verifiable data such as the rate of inflation or the loss of purchasing power of the dollar or the increasing cost of bailouts. The book does a great job of breaking down our financial system with or without conspiracy theories.

Rich people use capitalism to hoard wealth. If you got rid of the Fed they'd have a million other ways to do it, they were already doing it long before the Fed existed. The issue is our reliance on interest-bearing loans to create money. I think we need to replace that, but none of the presidents who got killed (or anyone else in power) has ever proposed doing that in a manner that would actually diminish the wealthy's power. Invariably someone goes back to "Gold Standard!" the ridiculous right-wing glory days plea that would only fukk us up worse without improving anything.

I'm still confused where you're getting "less than 1 billion on direct cash payments". It was over $400 billion.That was a typo you should be able to see the context i meant to say we spent less than 1 billion on direct cash payments but spent trillions meaning the rest is money printed out of thin air via loans

And all money is printed out of thin air, that's always been the case.

I never said we independently intervened I simply said we intervened due to the context of what I was saying.Yes, we were there in support of NATO. You made it sound like we independently intervened in Libya's Civil War. How was it different than when we went after Milosevic as part of NATO in Serbia?

The context was I don’t get into conspiracy theories but the manner in which we intervened in Libya and paraded his dead body around i have never seen before which made me think otherwise. Take your example for instance, most Americans don’t even know who milosevic was or even that we intervened in Serbia. And once again when dealing with Serbia youre getting involved with US-Russia relations and communism vs capitalism etc which is why China and Russia opposed intervention in Serbia but with Libya there’s is none of that.

I saw ghadaffi’s dead body with a bullet hole in his head being dragged through the street on live tv. Osama bin laden was public enemy #1 and was synonymous with 9/11 yet they won’t even his dead body.

The Chinese and Russians didn't oppose NATO intervention in Serbia because of Communism, they opposed it because they feared it setting precedents with foreign intervention in their own separatist movements. And in 1999 when the USA went up against Milosevic in Kosovo, communism wasn't even a thing in Russia anymore.I never said we independently intervened I simply said we intervened due to the context of what I was saying.

The context was I don’t get into conspiracy theories but the manner in which we intervened in Libya and paraded his dead body around i have never seen before which made me think otherwise. Take your example for instance, most Americans don’t even know who milosevic was or even that we intervened in Serbia. And once again when dealing with Serbia youre getting involved with US-Russia relations and communism vs capitalism etc which is why China and Russia opposed intervention in Serbia but with Libya there’s is none of that.

Because Americans killed bin Laden. Americans didn't kill Ghadaffi, Libyans did, ones who had been personally involved in fighting him. There were wild videos of Saddam's death too.I saw ghadaffi’s dead body with a bullet hole in his head being dragged through the street on live tv. Osama bin laden was public enemy #1 and was synonymous with 9/11 yet they won’t even his dead body.

Ozymandeas

Veteran

Nah man, the people making up this shyt don't know more about how the Fed works than the fukking Kennedys do. They're not even using hard facts to underlie their research, most of it is conjecture and online rumors more than anything else.

They can't keep saying that the Kennedys are all deeply connected to power, that the elite know far all sorts of deep shyt about how the world really runs that they're not telling the rest of us, and yet that JFK didn't know who ran the Fed and didn't know what the consequences were for going at them. The suspension of disbelief required is too much.

Im hesitant to say anything because I have no clue. What I do know is you can find out 90% of what you want to know about someone or some group on the Internet in a ten minute search. People back in the 60s didn't have all that information. What would take hours pouring through books, reports and newspapers (and that's if the shyt was published) is condensed into minutes. JFK obviously knew who ran the Fed, knew the Rothschilds, etc. but, I'd wager that he knew the deep, dark and ugly secrets, things that would never be revealed to the public whereas today we have a surface level understanding but, that understanding is more broad as we can search almost everything there is to know. Either way, he obviously didn't think he would get killed. But like I said, I don't really want to speculate on that because I don't know. What I can say, is that shadow banking groups and dark money entities would certainly prefer to live in a world without internet or in the 60s as compared to now.

Im tired I keep making that typo but I meant to say less than 1 trillion of the 2 trillion stimulus was actually cash payments. Money hasn’t always been printed out of thin air that’s the whole point of thread. The money a bank could loan out for instance at one point was directly proportional to its cash or gold reserves. There were limits to how much a bank could loan or it would risk going bankrupt. With the federal reserve that’s no longer a problem because they’ll just get bailed out. All reward with no risk. We pay the price twice. First through our tax dollars and then through inflation.I'm referring to the theory that secret shadowy people are running the Fed or that they're knocking off US Presidents to maintain their power.

Rich people use capitalism to hoard wealth. If you got rid of the Fed they'd have a million other ways to do it, they were already doing it long before the Fed existed. The issue is our reliance on interest-bearing loans to create money. I think we need to replace that, but none of the presidents who got killed (or anyone else in power) has ever proposed doing that in a manner that would actually diminish the wealthy's power. Invariably someone goes back to "Gold Standard!" the ridiculous right-wing glory days plea that would only fukk us up worse without improving anything.

I'm still confused where you're getting "less than 1 billion on direct cash payments". It was over $400 billion.

And all money is printed out of thin air, that's always been the case.

The fed printed 1.5 TRILLION dollars to help just Wall Street before the 2 TRILLION dollars cares act. Now we have a new 2 TRILLION dollars stimulus on the way. This is money out of thin air.

It’s the same thing you’re just playing semantics...The Chinese and Russians didn't oppose NATO intervention in Serbia because of Communism, they opposed it because they feared it setting precedents with foreign intervention in their own separatist movements. And in 1999 when the USA went up against Milosevic in Kosovo, communism wasn't even a thing in Russia anymore.

Because Americans killed bin Laden. Americans didn't kill Ghadaffi, Libyans did, ones who had been personally involved in fighting him. There were wild videos of Saddam's death too.

That doesn’t explain why would ghadffis dead body being dragged through streets on the other side of the globe is acceptable to be shown on daytime tv but osama who is public enemy #1 not even a single photo of his body can be found anywhere. I’m talking about my personal view of the optics. You can’t be right or wrong here.

Nah they celebrate that every year in Spain with blackface.Don’t we celebrate thanksgiving because it comes from Spain driving the moors out

"Festival of Moors and Christians"

This. He wanted to get rid of American dollars as the reserve currency and replace it with a gold standard currently like we had before the federal reserve.

I don’t usually get into conspiracy theories but when I saw how they handled ghadaffi and Libya i knew 100% what it was about. He went from a person relatively unknown to most Americans to public enemy #1 almost overnight and soon as they had him killed you didnt hear a word about Libya. I never seen anything like that. When has America directly intervened in any country like that ever before? They showed his dead body being dragged through the streets with a bullet hole in his head on major news platforms like it he was an example and a lesson.

"We came, we saw, he died" - - Hillarry Clinton, US Secretary of State

Killing 500,000 Iraqi children was worth it-Madeline Albright US Secretary of State

This is the satanic filth you're dealing with

Okay, I get you on the trillion now.Im tired I keep making that typo but I meant to say less than 1 trillion of the 2 trillion stimulus was actually cash payments. Money hasn’t always been printed out of thin air that’s the whole point of thread. The money a bank could loan out for instance at one point was directly proportional to its cash or gold reserves. There were limits to how much a bank could loan or it would risk going bankrupt. With the federal reserve that’s no longer a problem because they’ll just get bailed out. All reward with no risk. We pay the price twice. First through our tax dollars and then through inflation.

The fed printed 1.5 TRILLION dollars to help just Wall Street before the 2 TRILLION dollars cares act. Now we have a new 2 TRILLION dollars stimulus on the way. This is money out of thin air.

But yes, money has always been printed out of thin air. The fact that it was proportional to gold reserves is meaningless because the money supply was still far greater than the actual gold reserves. The proportion used was completely artificial. Not to mention that the amount of gold increasing in bank reserves has no logical connection to an increase in money supply.

Anything we pay out of tax dollars isn't paid out of inflation. Tax dollars are removed from the money supply, so we always pay one or the other, not both.We pay the price twice. First through our tax dollars and then through inflation.

And there was out of control inflation long before the fed ever existed. I'm confused why y'all think global finances were gravy before the fed. Poor people's lives sucked back then as bad or worse than they suck now. Like I said, Silvio Gesell predicted the issues that loans-on-interest money causes long before the fed existed, he explained the rise-and-crash cycle from the 1880s. Whether the money is backed by gold or not doesn't change that.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 2K