Republicans once again rely on a misleading Obamacare factoid

“If you look at those families that have employer-based insurance, their premiums have increased by more than $4,300.”

— House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), remarks to the media, Jan. 4, 2017

With the election of Donald Trump, Republican lawmakers finally have the opportunity to repeal the Affordable Care Act, a.k.a. Obamacare. As a result, we’re hearing some talking points that were debunked long ago.

We’re not sure why these old chestnuts keep coming back. There are plenty of legitimate complaints one could make about the law, particularly the functioning of the Obamacare exchanges and premium-rate increases in certain states.

But Republicans seems to love this one, no matter how misguided it is. Vice President-elect Mike Pence, during a news conference on Capitol Hill, also offered a version of it: “American families have seen an increase in premiums of $5,000.”

Let’s explain, yet again, why this is wrong.

The Facts

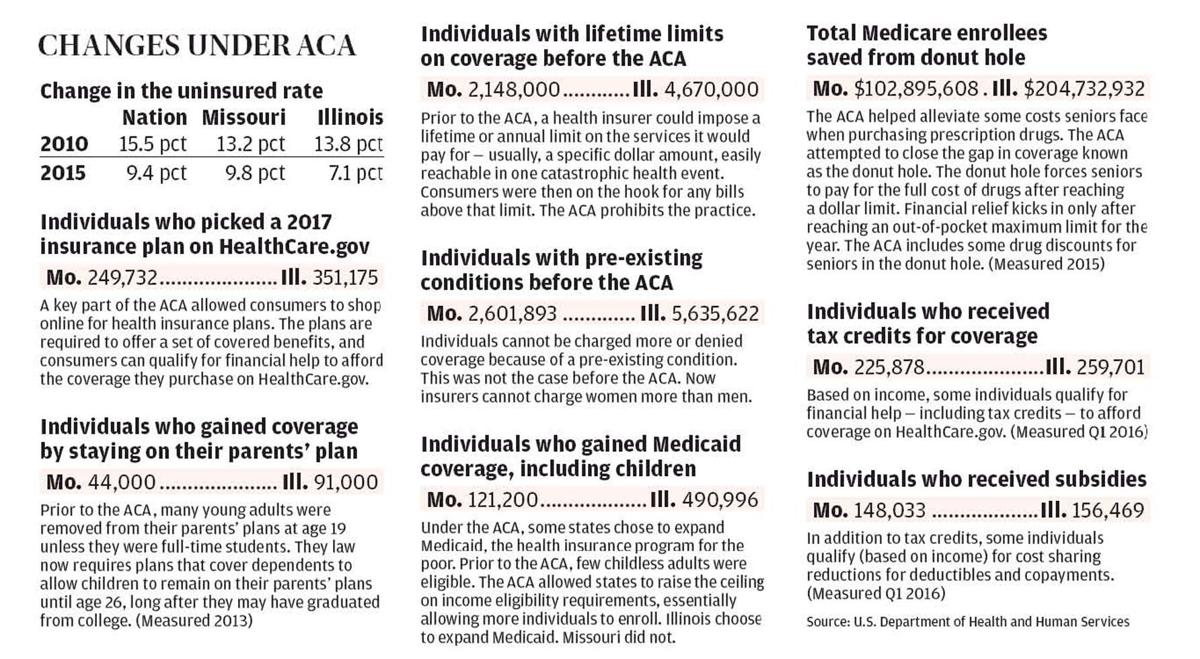

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 made important changes to the health-care market, but it was primarily aimed at people who do not get insurance through an employer and instead need to buy it themselves. When you hear about premium increases and trouble on the exchanges,

that has to do with the individual market. Most workers get their insurance through their employer, so the law’s effect has been much more muted. While the law did require an essential benefits package, large group plans were not required to do so — because most already covered such benefits.

With the use of this number, Republicans are trying to muddy these distinctions.

Then, the ad claimed that “the average cost of a family policy is up $1,300” as a result of the Affordable Care Act. The source was the

2011 Kaiser Family Foundation annual survey of employer health benefits, and the RNC simply took the difference between average family premium for 2011 ($15,073) and 2010 ($13,770).

At the time, few of the Affordable Care Act provisions had taken effect, so it was simply rather silly to blame the health-care law for the increase in premiums. The Kaiser report, in fact, noted that “many of the most significant provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) will take effect in 2014.”

Moreover, the survey is taken between January and May, meaning some of the data referred to the period before the law was even approved by Congress. The RNC

earned Three Pinocchios for that ad.

McCarthy’s number of $4,300 is simply an updated version of that old attack. The difference between the 2016 average annual premium ($18,141) and the 2010 premium is $4,371. (Note: Because these are employer-based health plans, most of the premiums are paid by employers. The average cost to workers increased just $1,386 over six years.)

McCarthy spokesman Matt Sparks justified the claim by noting — as the RNC ad did — that Obama had foolishly claimed in 2008 that his health-care plan would reduce health-care costs by $2,500 a year.

As we have noted before, Obama’s pledge came with a very large asterisk: He was not saying premiums would fall by $2,500, but that health-care costs per family would be that much lower than anticipated. In other words, if overall costs — not just premiums — were expected to rise by $5,000 by 2012, they would only rise by $2,500. Moreover, when Obama made this claim in 2008, he was quickly called out by fact checkers. The Fact Checker at the time

awarded Obama two Pinocchios for the pledge, saying it was based on shaky assumptions.

(In 2012,

we also gave Obama Three Pinocchios for claiming, as the law was about to go into effect, that health-insurance premiums would go down for small businesses and individuals. We noted that the law’s provisions, especially the requirement for insurance plans to cover essential benefits, would almost certainly increase premiums, though tax subsidies would help mitigate the impact for a little over half of the people in the exchanges.)

But here’s the funny thing: Health costs for employer-provided plans have grown much slower than expected since the Affordable Care Act was implemented.

“This is the fifth straight year of relatively low premium growth (family coverage growing between 3 and 4 percentage points each year),” Kaiser reported. The report noted that “the continuing implementation of the ACA does not appear to be causing major disruptions in employer market,” in part because existing plans were grandfathered in and did not need to meet Obamacare requirements, such as covering preventive benefits without cost. Twenty-three percent of covered workers are enrolled in a grandfathered plan.

“Relatively few employers made changes to working hours or hiring as a result of the [employer responsibility] provision, with more taking actions that increased coverage offers than reducing them, similar to the results last year,” Kaiser said.

Indeed, when the Kaiser report was released in September, the White House

trumpeted that the average family premium is now almost $3,600 lower than if premium growth had kept pace with the rate in the decade before the law was passed. We once

gave Obama Pinocchios for calling this reduction a “tax cut” — it is not — but certainly it is a good-news story that Republicans are trying to spin as bad news.

Now we should note that, among health-policy experts, the jury is still out on whether the ACA can be credited with the slowdown in health-care costs. The Great Recession led to slower growth in health-care costs in most of the 34 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (

See page 165.) Some experts say that the administration is rigging the figures by comparing the post-recession period to the high rates of the early 2000s, because it’s clear that the recession led to a sharp reduction in the growth of national health expenditures.

The White House has argued that, increasingly, some credit for the shift can be given to the ACA. “While there is evidence that the Great Recession placed downward pressure on health care cost growth in the early years of the recovery, it has now been more than six years since private-sector payrolls began to grow,”

wrote White House economists Jason Furman and Matt Fiedler. “Yet, as today’s data show, health care cost growth remains low. It is therefore increasingly likely that structural changes in the health care system — including changes in public policy and other factors that would have a persistent effect on health care spending over the long run — are the primary reasons health care cost growth remains low today.”

Kaiser

estimated that cumulative premium increases were 63 percent for 2001-2006, 31 percent for 2006-2011 and 20 percent for 2011-2016.

Premiums also may not tell the whole story, as employers in recent years have shifted costs to employees through higher deductibles and co-pays. (Kaiser says average deductibles have risen 63 percent from 2011 to 2016, though the White House says that is lower than the 2006-2010 trend line.)

So we also turned to another set of data, the

Milliman Medical Index, which attempts to calculate all out-of-pocket costs, not just premiums, for a typical U.S. family. But that exercise actually confirmed that the reduction is real for American health-care consumers — costs would have been nearly $5,000 higher if they had continued on the previous inflationary path.

“The Kaiser survey says premiums in the employer market have increased $4,300. That is a fact,” Sparks said. “President Obama said the law would reduce premiums by $2,500. That has not happened — not in the employer markets and not in the individual markets.”

He added that “the ACA did affect the employer market. The essential health benefits and many other changes apply to the employer market.”

The Pinocchio Test

This is an excellent example of a raw number that is offered with no context. Health-care premiums, like the costs of most goods, go up year after year. What matters is the rate of increase — and right now, health-care inflation is at its lowest rate in decades. On top of that, the number cited by Republicans has to do with employer-provided health-care premiums — and the employer market, thus far, has not been greatly affected by the law. Obamacare’s difficulties are in the individual market, so this is a case of mixing up apples and oranges.

This talking point deserves to be thrown on the ash heap of history. Republicans certainly need to come up with something better in making their case against the Affordable Care Act.

Republicans once again rely on a misleading Obamacare factoid