You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential "The Real Truth Is Wall Street Regulates Congress": The Offical Bernie Sanders CircleJerk Thread

More options

Who Replied?Dusty Bake Activate

Fukk your corny debates

Well I would hope we have a better safety net than 3rd world countries being that we're the richest nation in the world. Having a strong social safety net is a vital component to upward mobility out of poverty and this is proven a thousand times over throughout the industrialized world. I didn't suggest that having better projects and infinite food stamps is a solution. "Government dependency" is a red herring, and only an issue due to lack of opportunities for sustained work and wages. Virtually nobody actually WANTS to let people use their EBT card for cash, do petty dirt hustles, and live off the government if they felt they had a choice of something better. You are erroneously blaming "government dependency" as a causative factor when it's mostly just a rational survival strategy of people who have been marginalized by our socioeconomic model.Its a better safety net than in some third world countries. shyt its a better safety net than some developed countries like in France or Britain..You ever been to a ghetto for black immigrants in Paris or London? They would kill for the projects (which barely exist anymore thanks to section 8 and gentrification), EBT, WIC, schools and emergency room care. Having government build Trump tower level of public housing or providing infinite levels of food stamps for citizens in hood/urban areas isnt going to motivate alot of those people to become less dependent on government. They will just play the system to keep the government assistance rolling in..shyt its already happening now I got plenty folk in my family that sell their monthly EBT funds for cash

Also, Germany starts with a G and not a UGermany has free college because they have a brain drain.

totally different from th US, we can't expect their policies to apply here

In all fairness, USA is in the west and Germany is in the east, their policies are not compatibleLet's all remember that Nap is literally retarded and thinks that the raw number of colleges is more important than the number of students when it comes to providing tuition free education.

Well I would hope we have a better safety net than 3rd world countries being that we're the richest nation in the world. Having a strong social safety net is a vital component to upward mobility out of poverty and this is proven a thousand times over throughout the industrialized world. I didn't suggest that having better projects and infinite food stamps is a solution. "Government dependency" is a red herring, and only an issue due to lack of opportunities for sustained work and wages. Virtually nobody actually WANTS to let people use their EBT card for cash, do petty dirt hustles, and live off the government if they felt they had a choice of something better. You are erroneously blaming "government dependency" as a causative factor when it's mostly just a rational survival strategy of people who have been marginalized by our socioeconomic model.

The U.S. has a strong social net though already. Could it be better? Sure, but it will never be a nanny state type situation where the government is paving all housing and roads out of gold for the proletariat like the B.ernie B.ro C.oalition wants. Government dependency I would argue is not a red herring but a plausible issue, especially as it pertains to black folk as a percent on Snap and subsidized housing because the lack of opportunity is a symptom of our primary education system not catching up to what is demanded for jobs in the 21st century. Its why I hate the #BBC prescription for free college..Black males arent even getting off first base by graduating in four years from high school like other groups. And then the cycle is to revert to crime and degenerateness just to get by daily. These issues cause government dependency for which alot of these politicians cannot and will not address. So many people are brainwashed due to generations of dependency that theres a subculture in the black community that think it is cool to finesse food stamps and Social Security Insurance..Have these people been marginalized by our economic system? Sure..but that doesnt mean a subculture hasnt developed because it has, and government dependency is the driver of that culture.

Against Fortress Liberalism

For forty years, liberals have accepted defeat and called it “incremental progress.” Bernie Sanders offers a different way forward.

by Matt Karp

Bernie Sanders in the South Bronx on March 31, 2016. Michael Vadon / Flickr

The primary campaign between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders has produced the most direct ideological battle the Democratic Party has seen in a generation. It’s not just the policy differences that separate Sanders’s blunt social-democratic platform from Clinton’s neoliberal grab bag. The two candidates embody clashing theories of politics — alternative visions of how to achieve progressive goals within the American political system.

The Bernie Sanders model of change has all the subtlety of an index finger raised high above a debate podium. Lay out a bold, unapologetic vision of reform that speaks directly to people’s basic needs. Connect that vision to existing popular struggles, while mobilizing a broad and passionate coalition to support it (#NotMeUs). Ride this wave of democratic energy to overwhelm right-wing opposition and enact major structural reforms.

The Hillary Clinton model of change, on the other hand, begins not with policy or people but with a politician. Choose an experienced, practical leader who explicitly rejects unrealistic goals. Rally around that leader’s personal qualifications, while defending past achievements and stressing the value of party loyalty (#ImWithHer). Draw on the leader’s expertise to grind away at Congress and accumulate incremental victories that add up to significant reform.

For most of the Left, Clinton-style “incrementalism” is just a code word to disguise what is effectively a right-wing retrenchment. Nevertheless many self-identified progressives have backed Clinton’s “theory of politics” as the most realistic path to achieve Sanders’s objectives.

“As a temperamentally moderate figure,” the liberal Boston Globeargued, Clinton is best positioned to “take concrete steps to get relevant legislation enacted.”

Other editorial boards, corporate legal bloggers, and billionaires in the back seats of limousines have likewise endorsed the Clinton model as the only serious form of politics in a polarized republic. But they struggle to identify a major progressive victory that Clinton-style incrementalism has won in the past half-century.

Clinton’s eight-year term in the Senate produced bills to regulate video game violence and flag burning, both of which died in committee.

Bill Clinton’s eight-year term in the White House gave us an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit and a small children’s health insurance program — but also NAFTA, the 1994 crime bill, welfare reform, the Defense of Marriage Act, financial deregulation, and a grand bargain to gut Social Security that was only thwarted by a timely sex scandal.

The pragmatic, piecemeal, and irreproachably moderateachievements of Jimmy Carter are still more dispiriting. Even judged by the charitable standards of American liberalism, the forty-year balance sheet of “incremental progress” is decidedly negative.

Beltway pundits scoff at Sanders’s model of change, meanwhile, as if the Vermont senator thinks he can defeat a Republican Congress by getting a few hundred protestors to yell slogans outside Capitol Hill.

They naturally fail to mention that as a matter of historical record, the Sanders model happened to produce Social Security, the National Labor Relations Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, and Medicaid.

The simple truth is that virtually every significant and lasting progressive achievement of the past hundred years was achieved not by patient, responsible gradualism, but through brief flurries of bold action. The Second New Deal in 1935–36 and Civil Rights and the Great Society in 1964–65 are the outstanding examples, but the more ambiguous victories of the Obama era fit the pattern, too.

These reforms came in a larger political environment characterized by intense popular mobilization — the more intense the mobilization, the more meaningful the reform. And each of them was overseen by an unapologetically liberal president who hawked a sweeping agenda and rode it all the way to a landslide victory against a weakened right-wing opposition.

All three bursts of reform, of course, were shaped by the need to deal with opponents in Congress — including conservative Democrats — who imposed their own conditions. And even the New Deal and the Great Society, of course, were profoundly compromised in ways that no one on the Left is likely to forget.

Nevertheless these were real victories. None of them was won in the name of moderation, incrementalism, or the sober-minded rejection of ambitious goals.

At the 1936 Democratic convention, Franklin Roosevelt famously called for a “rendezvous with destiny,” not a rendezvous with tax credits for small businesses. Roosevelt took it as his duty to push against the boundaries of the politically possible, not surrender to them: “Today we stand committed to the proposition that freedom is no half-and-half affair. If the average citizen is guaranteed equal opportunity in the polling place, he must have equal opportunity in the market place.”

“There are those timid souls who say this battle cannot be won; that we are condemned to a soulless wealth,” declared Lyndon Johnson in 1964. “I do not agree. We have the power to shape the civilization that we want.”

Compare that to our current Democratic front-runner, whose most impassioned moment on the 2016 campaign trail came when she denounced single-payer health care as an idea “that will never, ever come to pass.”

With New York’s closed primary around the corner, Hillary Clinton has made a special virtue of her career-long party registration. But if anybody is looking for the Democratic tradition of Roosevelt and Johnson, surely Bernie Sanders is its heir.

Fortress Liberalism

Of course, liberal incrementalists rule out this kind of talk at once: don’t you know the Republicans control Congress? 1936 and 1964 are irrelevant precedents, because the central fact of our political lives is the dominance of the Republican Party.

In this view right-wing opposition is not to be dislodged, let alone defeated. At best, it is to be resisted from within the walls of the Democratic Party fortress known as the White House. “The next Democratic presidential term will be mostly defensive,” writesJonathan Chait — no more or less than a “bulwark” against Republican extremism in Congress.

This kind of “fortress liberalism,” to adapt a phrase of Rich Yeselson’s, is the dominant mentality within today’s Democratic establishment. In some ways, it’s a welcome retreat from the 1990s, when the Clintons and their allies worked actively to drive the party to the right. With the significant exceptions of education and trade policy, the post-2010 Obama era has been much more ideologically quiescent.

But fortress liberalism has been pernicious in its own way, especially for the millions of struggling Americans stranded outside the fortress.

Seldom do establishment Democrats stop to consider whether this negative mentality — both disturbingly complacent and profoundly uninspiring — has contributed to the steady evisceration of the party at the state level.

According to pollsters, political scientists, and their own tribunes, Democrats are now the dominant national party in the United States. (They have, after all, won the popular vote in five of the last six presidential elections.) Yet since 2009 Democrats have lost a record nine-hundred state legislative seats, thirty state chambers, and twelve governorships.

Not since George McClellan took command of the Army of the Potomac has American history witnessed such a wonderful capacity for dealing from strength but still getting crushed every time.

For many older liberals, moderate incrementalism is a response to the political disappointments of the last forty years. Unquestionably, for laborers, leftists and liberals alike, the post-1970s period has been an era of profound defeat.

And as Arthur Goldhammer observes in one of the wisest of the many jaded-elders-for-Hillary think pieces, it’s wrong to think the Democratic Party turned rightward chiefly because of the personal malice of the Clinton family.

The erosion of labor unions, the retreat of social democracy, and the rise of an aggressive right are products of both contingent political struggles and larger historical transformations that extend beyond American borders.

Yet as Zach Goldhammer writes in a powerful rejoinder to his father, the bittersweet melancholia of defeated liberals is also a strategic blindness. Neither the structural conditions nor the political configurations of 1980 or 1992 apply to 2016.

Across the industrialized world, forty years of flattened wages and concentrated wealth have created deep resentments among voters left behind. Many of them have turned toward the ethnic-nationalist right. But in both Europe and in the United States there are signs that the Left is gaining strength for the first time in decades.

Last year Gallup found that more Americans identify as “working class” than at any time in this century. According the General Social Survey, Americans under thirty-five are by far the most likely to adopt this class identity — by 2014, over 56 percent considered themselves members of the “working class.”

These young Americans have grown up outside the shadows of theCold War, but deep within the gloom of a triumphant global capitalism. They are Bernie Sanders’s base, and they have begun to shift the entire spectrum of American politics to the Left.

The energy of Black Lives Matter and Fight For 15 — activist movements whose scope and ambition did not exist a generation ago — is one sure marker of change.

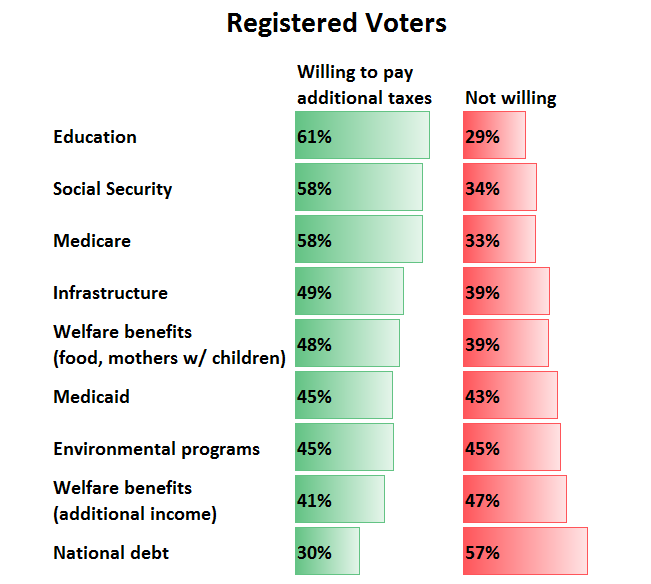

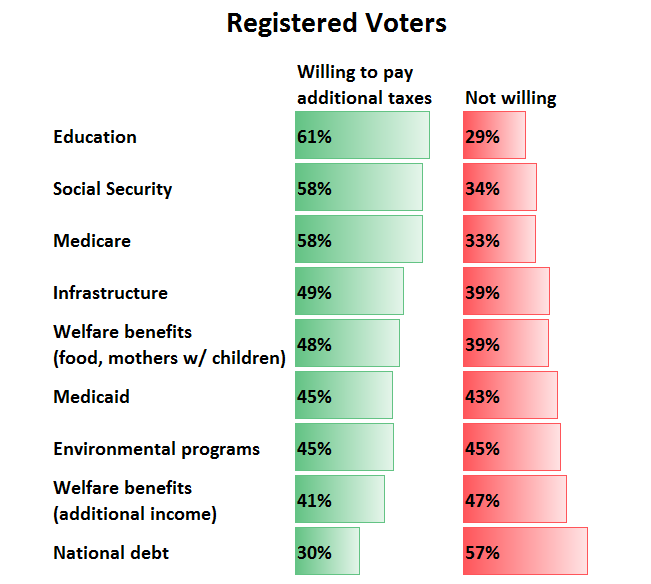

A less dramatic but equally significant development is the startling willingness of American voters to accept new taxes.

Last week Vox and Morning Consult polled registered voters about whether they were “willing to pay additional taxes” to fund certain programs.

For forty years, liberals have accepted defeat and called it “incremental progress.” Bernie Sanders offers a different way forward.

by Matt Karp

Bernie Sanders in the South Bronx on March 31, 2016. Michael Vadon / Flickr

- 3.33k

The primary campaign between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders has produced the most direct ideological battle the Democratic Party has seen in a generation. It’s not just the policy differences that separate Sanders’s blunt social-democratic platform from Clinton’s neoliberal grab bag. The two candidates embody clashing theories of politics — alternative visions of how to achieve progressive goals within the American political system.

The Bernie Sanders model of change has all the subtlety of an index finger raised high above a debate podium. Lay out a bold, unapologetic vision of reform that speaks directly to people’s basic needs. Connect that vision to existing popular struggles, while mobilizing a broad and passionate coalition to support it (#NotMeUs). Ride this wave of democratic energy to overwhelm right-wing opposition and enact major structural reforms.

The Hillary Clinton model of change, on the other hand, begins not with policy or people but with a politician. Choose an experienced, practical leader who explicitly rejects unrealistic goals. Rally around that leader’s personal qualifications, while defending past achievements and stressing the value of party loyalty (#ImWithHer). Draw on the leader’s expertise to grind away at Congress and accumulate incremental victories that add up to significant reform.

For most of the Left, Clinton-style “incrementalism” is just a code word to disguise what is effectively a right-wing retrenchment. Nevertheless many self-identified progressives have backed Clinton’s “theory of politics” as the most realistic path to achieve Sanders’s objectives.

“As a temperamentally moderate figure,” the liberal Boston Globeargued, Clinton is best positioned to “take concrete steps to get relevant legislation enacted.”

Other editorial boards, corporate legal bloggers, and billionaires in the back seats of limousines have likewise endorsed the Clinton model as the only serious form of politics in a polarized republic. But they struggle to identify a major progressive victory that Clinton-style incrementalism has won in the past half-century.

Clinton’s eight-year term in the Senate produced bills to regulate video game violence and flag burning, both of which died in committee.

Bill Clinton’s eight-year term in the White House gave us an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit and a small children’s health insurance program — but also NAFTA, the 1994 crime bill, welfare reform, the Defense of Marriage Act, financial deregulation, and a grand bargain to gut Social Security that was only thwarted by a timely sex scandal.

The pragmatic, piecemeal, and irreproachably moderateachievements of Jimmy Carter are still more dispiriting. Even judged by the charitable standards of American liberalism, the forty-year balance sheet of “incremental progress” is decidedly negative.

Beltway pundits scoff at Sanders’s model of change, meanwhile, as if the Vermont senator thinks he can defeat a Republican Congress by getting a few hundred protestors to yell slogans outside Capitol Hill.

They naturally fail to mention that as a matter of historical record, the Sanders model happened to produce Social Security, the National Labor Relations Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, and Medicaid.

The simple truth is that virtually every significant and lasting progressive achievement of the past hundred years was achieved not by patient, responsible gradualism, but through brief flurries of bold action. The Second New Deal in 1935–36 and Civil Rights and the Great Society in 1964–65 are the outstanding examples, but the more ambiguous victories of the Obama era fit the pattern, too.

These reforms came in a larger political environment characterized by intense popular mobilization — the more intense the mobilization, the more meaningful the reform. And each of them was overseen by an unapologetically liberal president who hawked a sweeping agenda and rode it all the way to a landslide victory against a weakened right-wing opposition.

All three bursts of reform, of course, were shaped by the need to deal with opponents in Congress — including conservative Democrats — who imposed their own conditions. And even the New Deal and the Great Society, of course, were profoundly compromised in ways that no one on the Left is likely to forget.

Nevertheless these were real victories. None of them was won in the name of moderation, incrementalism, or the sober-minded rejection of ambitious goals.

At the 1936 Democratic convention, Franklin Roosevelt famously called for a “rendezvous with destiny,” not a rendezvous with tax credits for small businesses. Roosevelt took it as his duty to push against the boundaries of the politically possible, not surrender to them: “Today we stand committed to the proposition that freedom is no half-and-half affair. If the average citizen is guaranteed equal opportunity in the polling place, he must have equal opportunity in the market place.”

“There are those timid souls who say this battle cannot be won; that we are condemned to a soulless wealth,” declared Lyndon Johnson in 1964. “I do not agree. We have the power to shape the civilization that we want.”

Compare that to our current Democratic front-runner, whose most impassioned moment on the 2016 campaign trail came when she denounced single-payer health care as an idea “that will never, ever come to pass.”

With New York’s closed primary around the corner, Hillary Clinton has made a special virtue of her career-long party registration. But if anybody is looking for the Democratic tradition of Roosevelt and Johnson, surely Bernie Sanders is its heir.

Fortress Liberalism

Of course, liberal incrementalists rule out this kind of talk at once: don’t you know the Republicans control Congress? 1936 and 1964 are irrelevant precedents, because the central fact of our political lives is the dominance of the Republican Party.

In this view right-wing opposition is not to be dislodged, let alone defeated. At best, it is to be resisted from within the walls of the Democratic Party fortress known as the White House. “The next Democratic presidential term will be mostly defensive,” writesJonathan Chait — no more or less than a “bulwark” against Republican extremism in Congress.

This kind of “fortress liberalism,” to adapt a phrase of Rich Yeselson’s, is the dominant mentality within today’s Democratic establishment. In some ways, it’s a welcome retreat from the 1990s, when the Clintons and their allies worked actively to drive the party to the right. With the significant exceptions of education and trade policy, the post-2010 Obama era has been much more ideologically quiescent.

But fortress liberalism has been pernicious in its own way, especially for the millions of struggling Americans stranded outside the fortress.

Seldom do establishment Democrats stop to consider whether this negative mentality — both disturbingly complacent and profoundly uninspiring — has contributed to the steady evisceration of the party at the state level.

According to pollsters, political scientists, and their own tribunes, Democrats are now the dominant national party in the United States. (They have, after all, won the popular vote in five of the last six presidential elections.) Yet since 2009 Democrats have lost a record nine-hundred state legislative seats, thirty state chambers, and twelve governorships.

Not since George McClellan took command of the Army of the Potomac has American history witnessed such a wonderful capacity for dealing from strength but still getting crushed every time.

For many older liberals, moderate incrementalism is a response to the political disappointments of the last forty years. Unquestionably, for laborers, leftists and liberals alike, the post-1970s period has been an era of profound defeat.

And as Arthur Goldhammer observes in one of the wisest of the many jaded-elders-for-Hillary think pieces, it’s wrong to think the Democratic Party turned rightward chiefly because of the personal malice of the Clinton family.

The erosion of labor unions, the retreat of social democracy, and the rise of an aggressive right are products of both contingent political struggles and larger historical transformations that extend beyond American borders.

Yet as Zach Goldhammer writes in a powerful rejoinder to his father, the bittersweet melancholia of defeated liberals is also a strategic blindness. Neither the structural conditions nor the political configurations of 1980 or 1992 apply to 2016.

Across the industrialized world, forty years of flattened wages and concentrated wealth have created deep resentments among voters left behind. Many of them have turned toward the ethnic-nationalist right. But in both Europe and in the United States there are signs that the Left is gaining strength for the first time in decades.

Last year Gallup found that more Americans identify as “working class” than at any time in this century. According the General Social Survey, Americans under thirty-five are by far the most likely to adopt this class identity — by 2014, over 56 percent considered themselves members of the “working class.”

These young Americans have grown up outside the shadows of theCold War, but deep within the gloom of a triumphant global capitalism. They are Bernie Sanders’s base, and they have begun to shift the entire spectrum of American politics to the Left.

The energy of Black Lives Matter and Fight For 15 — activist movements whose scope and ambition did not exist a generation ago — is one sure marker of change.

A less dramatic but equally significant development is the startling willingness of American voters to accept new taxes.

Last week Vox and Morning Consult polled registered voters about whether they were “willing to pay additional taxes” to fund certain programs.

Naturally Vox reported the results as a repudiation of the Sanders agenda, even though few of Sanders’s programs would be paid for by individual tax hikes, and none of them would be pitched in such a politically clueless fashion. (Sanders’s single-payer health plan, even skeptics at PolitiFact admit, would help the average American family save hundreds if not thousands of dollars a year.)

But since the Right and the elite media do adopt this reactionary way of framing tax questions, it’s useful to see how Americans respond when confronted with it. Especially since the results showed that most American voters are willing to pay higher taxes in order to provide universal, progressive goods — Social Security, Medicare, education, and infrastructure improvements.

Remember, this poll asked voters not just if they support new taxes in a general sense — never mind taxes on the wealthy! — but if they are willing, individually, to pay more out of their own pockets. They are. And voters under forty-five appear eager to pay additional taxes for almost everything:

This is not the American electorate of 1992. In that year, the populist outsider in the Democratic primary, a former governor of California, made the centerpiece of his progressive agenda a flat tax.

In 2016, the populist outsider in the Democratic primary, a socialist from Vermont, just forced the overwhelming party favorite to endorse, against her own record and personal belief, a doubling of the minimum wage. Times have changed, and the balance of forces has changed with them.

Trumpocalypse Now

So 2016 isn’t 1992: does that mean it really could be 1964? Maybe not. But it’s frustrating to see fortress liberals so consistently assume rather than investigate the electoral power of the Right.

In February, they dismissed polls showing Bernie Sanders defeating all GOP contenders as too early to be meaningful. (Never mind that February polls have closely predicted five consecutive elections.) Now it’s mid-April, when political science scholarship shows that trial heat polls are very predictive, but somehow Sanders’s even larger leads remain meaningless.

“Just wait until voters learn more about him!” (Sanders is already by far the third-best-known candidate in the race, and his favorabilitydwarfs the other contenders.) “Just wait until the Republicans start calling him a communist!” (Donald Trump, Fox News, multiple GOPsenators, and many others have been doing that for months.) “But just wait until they put Sanders on the cover of National Review! That’ll stop him!” Wait a minute.

There is no value in underestimating the Right, but even less value in offering McClellan-like overestimates of its strength.

The Republican surge of 2014 was generated by just 36 percent of the eligible voting population. Right-wing tax rebels, flush withKochtopus money and running against tepid, defensive Democrats, are capable of winning a low-turnout midterm election. But modern Republicans are weak opponents in presidential elections, where the electorate is almost 50 percent larger.

Even if the GOP were cruising toward a coronation of a unifying, twenty-first century conservative leader, Republicans would be underdogs in a national presidential race. But at least under those circumstances there might be reason to forgive fortress liberals for bustling about with their beloved siege defenses.

Instead, the 2016 Republican Party is tearing itself apart in a way that hasn’t happened in generations, and probably won’t happen again for generations to come.

Either of the two men almost assured to get the Republican nomination, Donald Trump or Ted Cruz, would represent the least popular nominee a major party has ever produced. (They’re even less well-liked than Hillary Clinton, which is saying something.)

Now is not the time to bar the doors of the fortress; it’s time to take the ideological struggle to the enemy. How many chances will American liberals have to do battle against a foe whose chief representative is a red-faced billionaire charlatan, secure in the loathing of half his own party and two-thirds of the United States?

The Trumpocalypse will probably only come once in our lifetimes. A landslide on the scale of 1964 may be out of reach, but with a large and passionate electorate mobilized in opposition to a terminally unpopular opponent, a major Democratic wave is certainly possible.

On both an ideological and a tactical level, 2016 represents a historical moment rife with opportunity for the Bernie Sanders model of politics. Who knows when we will see another like it?

Mass Times Acceleration

The liberal refusal even to acknowledge this opportunity speaks to an even more profound shift within the Democratic Party. The Sanders model, above all, is a vision of mass politics. For over two hundred years, it was more or less obvious that this is the only way democratic progress can occur in an unequal society — by summoning the power of the people against entrenched interests.

Only in the last few decades has the Democratic Party become confused on this point. Vox even had to run an “explainer” (not a bad one!) on the Sanders model of change, which after all was summarized pretty well by Percy Shelley back in 1819: “ye are many — they are few.”

The confusion comes because Democrats have not only distanced themselves from working-class voters and redistributive economics, as Tom Frank argues in his new polemic, Listen, Liberal. Scarred by the rise of a populist Republican Party, elite liberals have gone beyond skepticism about popular insurgency and arrived at an active hostility toward mass politics itself.

Mass politics just does not compute with the professional-class worldview that suffuses today’s Democratic Party. For liberal elites, effective political struggle is something that happens inside committee rooms, not at strikes, rallies, or protests. (The Clinton campaign itself embodies this vision of the world, where politics means deal-making and democracy means voting — nothing less and nothing more.)

To the extent that outdoor struggle counts at all, liberal professionals tend to see it as a raw expression of emotion or identity — a phenomenon that is sometimes to be praised and other times to be admonished. Seldom does it figure as a popular mobilization that can actually shape political outcomes.

Here is another reason why Hillary Clinton’s appeal to incremental progress strikes such a powerful chord with the party, the media, and the affluent Democrats who are among her most reliable bases of support.

Clinton’s presentation of herself as a painstaking, detail-oriented manager matches a recognizable professional-class model of achievement.

Like Barack Obama’s seminar-room equanimity, or Justin Trudeau’s unrugged good looks — straight from the computer science lecture hall of your dreams — Clinton’s industrious incrementalism suits the self-image of a well-graduated expert class, for whom university educations are such critical markers of status and identity.

Compared to these familiar meritocratic types, the Sanders campaign appears curious if not simply illegible. Hence the confused attemptsto relate a social democrat with nearly half his party’s support to pallid “progressives” like Howard Dean, who couldn’t manage even a fifth of the primary vote in liberal Wisconsin. If Bill Bradley won a majority of young black and Latino Democrats, or Jerry Brown turned out eighteen thousand people to a rally in the Bronx, history must have missed it.

Ironically it is university students themselves — less certain of their own class position than generations past — who have responded most warmly to his call for a revival of mass politics.

Unlike fortress liberals or professional elites, Sanders and his young backers recognize that the vital element in any progressive struggle is the ability to generate energy from the bottom up.

Indoor expertise without outdoor protest; shrewd deal-making without mass mobilization; mastery of details without popular momentum — these are the proper tools of conservative politics, and have been since at least the era of Metternich.

Democratic struggle requires something else. In this election season, Max Weber’s dictum that politics is “a strong and slow boring of hard boards” has frequently been dragooned into duty as a grave defense of Clintonian incrementalism.

But the most famous carpentry analogy in the history of politics does not offer complex instructions on how to assemble an IKEA wall cabinet. Instead it insists on the vigorous application of force through a simple machine. It is Bernie Sanders, not Hillary Clinton, who seems to understand that the only way to produce force is by multiplying mass and acceleration.

But since the Right and the elite media do adopt this reactionary way of framing tax questions, it’s useful to see how Americans respond when confronted with it. Especially since the results showed that most American voters are willing to pay higher taxes in order to provide universal, progressive goods — Social Security, Medicare, education, and infrastructure improvements.

Remember, this poll asked voters not just if they support new taxes in a general sense — never mind taxes on the wealthy! — but if they are willing, individually, to pay more out of their own pockets. They are. And voters under forty-five appear eager to pay additional taxes for almost everything:

This is not the American electorate of 1992. In that year, the populist outsider in the Democratic primary, a former governor of California, made the centerpiece of his progressive agenda a flat tax.

In 2016, the populist outsider in the Democratic primary, a socialist from Vermont, just forced the overwhelming party favorite to endorse, against her own record and personal belief, a doubling of the minimum wage. Times have changed, and the balance of forces has changed with them.

Trumpocalypse Now

So 2016 isn’t 1992: does that mean it really could be 1964? Maybe not. But it’s frustrating to see fortress liberals so consistently assume rather than investigate the electoral power of the Right.

In February, they dismissed polls showing Bernie Sanders defeating all GOP contenders as too early to be meaningful. (Never mind that February polls have closely predicted five consecutive elections.) Now it’s mid-April, when political science scholarship shows that trial heat polls are very predictive, but somehow Sanders’s even larger leads remain meaningless.

“Just wait until voters learn more about him!” (Sanders is already by far the third-best-known candidate in the race, and his favorabilitydwarfs the other contenders.) “Just wait until the Republicans start calling him a communist!” (Donald Trump, Fox News, multiple GOPsenators, and many others have been doing that for months.) “But just wait until they put Sanders on the cover of National Review! That’ll stop him!” Wait a minute.

There is no value in underestimating the Right, but even less value in offering McClellan-like overestimates of its strength.

The Republican surge of 2014 was generated by just 36 percent of the eligible voting population. Right-wing tax rebels, flush withKochtopus money and running against tepid, defensive Democrats, are capable of winning a low-turnout midterm election. But modern Republicans are weak opponents in presidential elections, where the electorate is almost 50 percent larger.

Even if the GOP were cruising toward a coronation of a unifying, twenty-first century conservative leader, Republicans would be underdogs in a national presidential race. But at least under those circumstances there might be reason to forgive fortress liberals for bustling about with their beloved siege defenses.

Instead, the 2016 Republican Party is tearing itself apart in a way that hasn’t happened in generations, and probably won’t happen again for generations to come.

Either of the two men almost assured to get the Republican nomination, Donald Trump or Ted Cruz, would represent the least popular nominee a major party has ever produced. (They’re even less well-liked than Hillary Clinton, which is saying something.)

Now is not the time to bar the doors of the fortress; it’s time to take the ideological struggle to the enemy. How many chances will American liberals have to do battle against a foe whose chief representative is a red-faced billionaire charlatan, secure in the loathing of half his own party and two-thirds of the United States?

The Trumpocalypse will probably only come once in our lifetimes. A landslide on the scale of 1964 may be out of reach, but with a large and passionate electorate mobilized in opposition to a terminally unpopular opponent, a major Democratic wave is certainly possible.

On both an ideological and a tactical level, 2016 represents a historical moment rife with opportunity for the Bernie Sanders model of politics. Who knows when we will see another like it?

Mass Times Acceleration

The liberal refusal even to acknowledge this opportunity speaks to an even more profound shift within the Democratic Party. The Sanders model, above all, is a vision of mass politics. For over two hundred years, it was more or less obvious that this is the only way democratic progress can occur in an unequal society — by summoning the power of the people against entrenched interests.

Only in the last few decades has the Democratic Party become confused on this point. Vox even had to run an “explainer” (not a bad one!) on the Sanders model of change, which after all was summarized pretty well by Percy Shelley back in 1819: “ye are many — they are few.”

The confusion comes because Democrats have not only distanced themselves from working-class voters and redistributive economics, as Tom Frank argues in his new polemic, Listen, Liberal. Scarred by the rise of a populist Republican Party, elite liberals have gone beyond skepticism about popular insurgency and arrived at an active hostility toward mass politics itself.

Mass politics just does not compute with the professional-class worldview that suffuses today’s Democratic Party. For liberal elites, effective political struggle is something that happens inside committee rooms, not at strikes, rallies, or protests. (The Clinton campaign itself embodies this vision of the world, where politics means deal-making and democracy means voting — nothing less and nothing more.)

To the extent that outdoor struggle counts at all, liberal professionals tend to see it as a raw expression of emotion or identity — a phenomenon that is sometimes to be praised and other times to be admonished. Seldom does it figure as a popular mobilization that can actually shape political outcomes.

Here is another reason why Hillary Clinton’s appeal to incremental progress strikes such a powerful chord with the party, the media, and the affluent Democrats who are among her most reliable bases of support.

Clinton’s presentation of herself as a painstaking, detail-oriented manager matches a recognizable professional-class model of achievement.

Like Barack Obama’s seminar-room equanimity, or Justin Trudeau’s unrugged good looks — straight from the computer science lecture hall of your dreams — Clinton’s industrious incrementalism suits the self-image of a well-graduated expert class, for whom university educations are such critical markers of status and identity.

Compared to these familiar meritocratic types, the Sanders campaign appears curious if not simply illegible. Hence the confused attemptsto relate a social democrat with nearly half his party’s support to pallid “progressives” like Howard Dean, who couldn’t manage even a fifth of the primary vote in liberal Wisconsin. If Bill Bradley won a majority of young black and Latino Democrats, or Jerry Brown turned out eighteen thousand people to a rally in the Bronx, history must have missed it.

Ironically it is university students themselves — less certain of their own class position than generations past — who have responded most warmly to his call for a revival of mass politics.

Unlike fortress liberals or professional elites, Sanders and his young backers recognize that the vital element in any progressive struggle is the ability to generate energy from the bottom up.

Indoor expertise without outdoor protest; shrewd deal-making without mass mobilization; mastery of details without popular momentum — these are the proper tools of conservative politics, and have been since at least the era of Metternich.

Democratic struggle requires something else. In this election season, Max Weber’s dictum that politics is “a strong and slow boring of hard boards” has frequently been dragooned into duty as a grave defense of Clintonian incrementalism.

But the most famous carpentry analogy in the history of politics does not offer complex instructions on how to assemble an IKEA wall cabinet. Instead it insists on the vigorous application of force through a simple machine. It is Bernie Sanders, not Hillary Clinton, who seems to understand that the only way to produce force is by multiplying mass and acceleration.

Bernie Sanders’ Team Just Accused Hillary Clinton of Violating Campaign Finance Rules | VICE News

That Clooney dinner lines up with just the right limit to donate to the Victory Fund, but instead of using it for the down ticket like she says it goes right into her campaign.

But she's gonna fix money in politics

That Clooney dinner lines up with just the right limit to donate to the Victory Fund, but instead of using it for the down ticket like she says it goes right into her campaign.

But she's gonna fix money in politics

MrSinnister

Delete account when possible.

You see all the fukkers that used to dap me before I talked about Black empowerment. They actually think government is SUPPOSED to take care of their singular issues, like they're wards of the state and shytThe U.S. has a strong social net though already. Could it be better? Sure, but it will never be a nanny state type situation where the government is paving all housing and roads out of gold for the proletariat like the B.ernie B.ro C.oalition wants. Government dependency I would argue is not a red herring but a plausible issue, especially as it pertains to black folk as a percent on Snap and subsidized housing because the lack of opportunity is a symptom of our primary education system not catching up to what is demanded for jobs in the 21st century. Its why I hate the #BBC prescription for free college..Black males arent even getting off first base by graduating in four years from high school like other groups. And then the cycle is to revert to crime and degenerateness just to get by daily. These issues cause government dependency for which alot of these politicians cannot and will not address. So many people are brainwashed due to generations of dependency that theres a subculture in the black community that think it is cool to finesse food stamps and Social Security Insurance..Have these people been marginalized by our economic system? Sure..but that doesnt mean a subculture hasnt developed because it has, and government dependency is the driver of that culture.

.

.Bernie needed to offer free college, but I hope this is a process that we leg into, instead of jumping in, because it's going to be crazy expensive and hard to pass. It is a good move, because students are piling up tons of debt, for less job prospects, but these dudes these days are permanent children if you ask me. Obama didn't even go close to giving them what they wanted, but they expect Bernie to.

I'm for giving everyone fishing hooks, lines, and poles. Sometimes, I'd even give them bait. But these fukkers here want to own fish markets when someone else has done all the work. fukk em.

MrSinnister

Delete account when possible.

Nah, call it what is is, and stop dressing it up. You tell people to make better choices in life, at least procreation ones (the most expensive of all, especially emotionally), and you're suddenly the enemy. I've seen it over and over. There is a dependancy culture. Until that culture grows the fukk up, the GOP will always be in play. You can't have it where you drop out of school and then start immediately making babies when you have no savings, yet this is the norm in many neighborhoods, because subsistence is expected.Well I would hope we have a better safety net than 3rd world countries being that we're the richest nation in the world. Having a strong social safety net is a vital component to upward mobility out of poverty and this is proven a thousand times over throughout the industrialized world. I didn't suggest that having better projects and infinite food stamps is a solution. "Government dependency" is a red herring, and only an issue due to lack of opportunities for sustained work and wages. Virtually nobody actually WANTS to let people use their EBT card for cash, do petty dirt hustles, and live off the government if they felt they had a choice of something better. You are erroneously blaming "government dependency" as a causative factor when it's mostly just a rational survival strategy of people who have been marginalized by our socioeconomic model.

You really think if they knew America would force people to starve from many decisions they make, people would continue making them?

If the parent was raised off Welfare, it's likely they won't parent the child away from it, unless they're one of the rare driven people, which is why benefits MUST be more incentivized, not cut. If you do X (which is a pathway off), you received Y, and then Z for a certain number of months. Like bank crimes having zero disincentives, Welfare has no incentives to leave it either, except in places like New York, that require you to check in with someone daily.

If the parent was raised off Welfare, it's likely they won't parent the child away from it, unless they're one of the rare driven people, which is why benefits MUST be more incentivized, not cut. If you do X (which is a pathway off), you received Y, and then Z for a certain number of months. Like bank crimes having zero disincentives, Welfare has no incentives to leave it either, except in places like New York, that require you to check in with someone daily.

Last edited:

I_Got_Da_Burna

Superstar

See...I'm not entirely clueless

I'm just saying...i'm not even against "free college"...but all this hand-waving and obfuscation of facts isn't helping the discussion.

public universities and colleges were free in the 70's...it was either the tail end of the Carter Adminsitration or the beginning of Reagan that they got rid of it, I believe. Anyway, it didn't crash anything, or create braindead people. It provided an educated workforce that was upwardly mobile and unhindered by large debt.

Again, not buying what you posted.