You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Official African American Thread#2

- Thread starter Rhapscallion Démone

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Musical Ambassadors: America Exports Jazz

I don't think many realize just how revolutionary and globalized Jazz really was/is. It truly was the default popular musical genre all over world really until Rock N Roll and then Soul came along.

Musical Ambassadors: America Exports Jazz

Beginning in the 1950s, the U.S. Department of State sent dozens of America’s greatest jazz musicians to tour the globe becoming known as “the Jazz Ambassadors.” These American jazz artists were embraced by enthusiastic audiences from Africa to the Middle East, Europe, Asia and Latin America. Many of the Jazz Ambassadors were equally eager to learn about the music and culture of their international hosts and often held impromptu jam sessions with local musicians. This selection of posters from the exhibition Jam Session organized by the Meridian International Center in Washington, D.C. several years ago. Find more on this past exhibition at http://www.meridian.org/jazzambassadors.

Recognizing the cross-cultural appeal of jazz, American Jazz Ambassadors were able to transcend national boundaries, build new cultural bridges, and tell a larger story about freedom in America. Jazz Ambassador Louis Armstrong explained it best as he sang on the album, The Real Ambassadors, produced in collaboration with fellow Jazz Ambassador Dave Brubeck and his wife, Iola: The State Department has discovered jazz; It reaches folks like nothing ever has. Like when they feel that jazzy rhythm, They know we’re really with ’em. That’s what we call cultural exchange.

I don't think many realize just how revolutionary and globalized Jazz really was/is. It truly was the default popular musical genre all over world really until Rock N Roll and then Soul came along.

Black Lightning

Superstar

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Slavery and the American University

Slavery and the American University

According to the surviving records, the first enslaved African in Massachusetts was the property of the schoolmaster of Harvard. Yale funded its first graduate-level courses and its first scholarship with the rents from a small slave plantation it owned in Rhode Island (the estate, in a stroke of historical irony, was named Whitehall). The scholarship’s first recipient went on to found Dartmouth, and a later grantee co-founded the College of New Jersey, known today as Princeton. Georgetown’s founders, prohibited by the rules of their faith from charging students tuition, planned to underwrite school operations in large part with slave sales and plantation profits, to which there was apparently no ecclesiastical objection. Columbia, when it was still King’s College, subsidized slave traders with below-market loans. Before she gained fame as a preacher and abolitionist, Sojourner Truth was owned by the family of Rutgers’s first president.

From their very beginnings, the American university and American slavery have been intertwined, but only recently are we beginning to understand how deeply. In part, this can be attributed to an expansion of political will. Barely two decades ago, questions raised by a group of scholars and activists about Brown University’s historic connection to slavery were met with what its then-president, Ruth Simmons, saw as insufficient answers, and so she appointed the first major university investigation. Not long before that, one of the earliest scholars to independently look into his university’s ties to slavery, a law professor at the University of Alabama, began digging through the archives in part to dispel a local myth, he wrote, that “blacks were not present on the campus” before 1963, when “Vivian Malone and James Hood enrolled with the help of Nicholas Katzenbach and the National Guard.” He found, instead, that they preceded its earliest students, and one of the university’s first acts was the purchase of an enslaved man named Ben. In Virginia, a small consortium founded three years ago to share findings and methods has expanded to include nearly three dozen colleges and universities across North America and two in European port cities. Almost all of these projects trace their origins to protests or undergraduate classes, where a generation of students, faculty, archivists, activists, and librarians created forums for articulating their questions, and for finding one another.

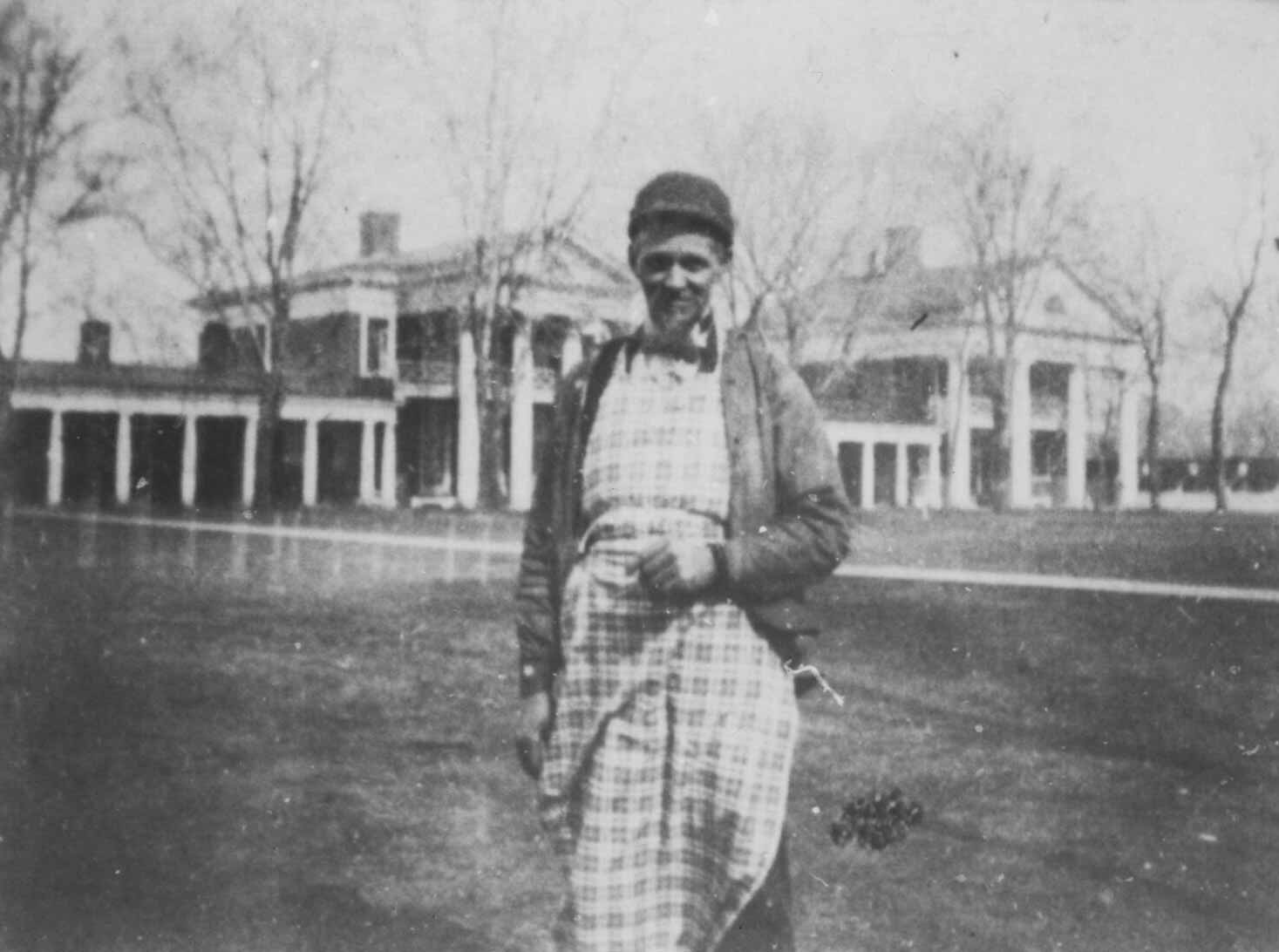

The University of VirginiaHenry Martin, born into slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate, began working at the University of Virginia in 1850 as a waiter and then a janitor; pictured here on the UVA lawn, 1896

But their progress is also due to a leap of historical imagination. When an archivist at St. Mary’s College of Maryland found incomplete records and few leads for his own research among collected letters and decades of minutes from the college’s board meetings, he wondered if he’d arrived at a dead end. He asked Georgetown alumnus Richard Cellini how Cellini had been able not only to identify the 272 men, women, and children that Georgetown University sold in 1838, but also to locate some of their living descendants. Cellini responded that he had looked outside the traditional corridors of history.

Most African Americans didn’t appear by name in the federal census until after the Civil War (though the “slave schedules” of 1850 and 1860 listed enslaved people under the entries for their owners, along with a few descriptive details), and plantation records often listed slaves by first name only. Journals and letters are rare; in many places, it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read or write. “Believe me, for decades and decades people at Georgetown believed that the slaves didn’t have surnames,” Cellini told the St. Mary’s archivist, and others insisted there had been no surviving descendants of the sale. More or less, Cellini concluded:

It’s because they didn’t look hard enough. Basically all they did was look inside the four walls of their own institution. There are actually multiple directions they could have gone: tax documents, sacramental records in churches, mortgage records, the Freedmen’s Bureau or, in our case, a ship manifest, and suddenly everybody’s last name appears.… It’s not that you can’t reach the conclusion that there is no documentation. It just takes a lot of hard work.

Once Cellini had the names, he hired a team of genealogists. Other projects have worked with community groups, oral histories, family stories passed from one generation to the next, clippings that had been tucked away in boxes and attics. And then there are the historians.

Library of Congress/Mason County Museum Maysville, Kentucky/Monticello FoundationLucy Cottrell, who was enslaved at Monticello, was purchased at Thomas Jefferson’s estate sale by UVA professor George Blaettermann; pictured here holding Blaettermann’s daughter, circa 1835

Archives have gaps, and methods of interpreting them can be flawed. Other evidence is sometimes hiding in plain sight. In 2012, at the University of Virginia, which had rented enslaved laborers both to construct the first buildings and to make their bricks, archeologists found—or, more precisely, refound—what is most likely a slave cemetery on campus, beneath what had been a plant nursery and two feet of topsoil. They left the graves undisturbed, put up protective fencing, and marked the grounds with explanatory panels. Other universities have tried to run from the past: when the University of Georgia made a similar discovery three years later, it tested and initially reburied the remains behind locked gates without announcement. The sole local witness, a retired alumnus named Fred O. Smith Sr., thought he might be watching the reinterment of his ancestors. The university’s treatment of the site had already become the source of a local controversy, and Smith arrived to watch the reburial after hearing from a local tipster that a new hole had been dug. He later told a reporter that when he was spotted, one of the workers moved a truck to block his view. “We may never arrive at the truth,” James Campbell, the chair of the Brown University investigation, noted at a conference shortly after the publication of its findings. “But we can at least ‘narrow the range of permissible lies.’”

The Brown report, published in 2006, found extensive connections between that university and the slave trade. According to historian Craig Steven Wilder’s Ebony and Ivy (2013)—a book, Wilder writes, that he had considered giving up on before reading the Brown study—“the high point of the African slave trade also marked, not coincidentally, the period in which higher education in the colonies expanded most rapidly.” In the middle decades of the eighteenth century, the number of colleges in Britain’s mainland colonies tripled as owners and captains of slave ships converted their profits into patronage and positions as trustees. A college’s survival could depend on its access to the economy of slavery and ability to attract what has been politely called “merchant wealth.” Before the colonies’ independence, it was this wealth that allowed the establishment and development of early colleges free from British meddling; after, northern schools’ efforts to fill their classes with the sons of Southern plantation owners allowed large swaths of the region to put off establishing new local universities.

University of VirginiaA ceremony at the Cemetery for the Enslaved, which was rediscovered in 2012, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, 2014

Universities are hardly the only American institutions to have grown from ties to slavery, but with this research they are among the first to acknowledge that their involvement was rarely recognized and poorly understood, and to mobilize the expertise and resources to change that. (The writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, speaking to Harvard’s president as the university publicized its own research about slavery last year, said that universities “have a knowledge that maybe the Chicago Police Department does not have yet.”) “What is the point of these kinds of enterprises?” Campbell, the Brown committee chair, now teaching at Stanford, has said to other historians hoping to expand this work. “I think none of us here is naive enough to believe that somehow with the act of a few universities uncovering the ways in which their histories are profoundly entangled with the institution of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade… the scales are going to fall from the eyes of our nation, and racism as we know it will come to an end.” He continued: “But what we can do is we can transform the way people talk about and understand the past, what they see when they look out on the landscape in which they live.” The gaps in our knowledge about the experience of American slavery are volumes and volumes wide. These projects have narrowed them, and will continue to do so, but they’ve also revealed how much has been lost, suppressed, or considered unworthy of preservation in the official record. Beyond the institutional histories they uncover, these projects reveal a kind of segregation of our national memory or, at the very least, a willful amnesia.

*

Last fall, after more than four years of research, Princeton became the latest university to present its results. Princeton was the site of a George Washington victory over British forces and housed the Continental Congress. All of the university’s founding trustees, and its first nine presidents, owned slaves. Slaves owned by the university’s fifth president—two women, a man, and three children—were auctioned off under the so-called “liberty trees” outside his house, two sycamores planted around the time of the repeal of the Stamp Act and pointed out on campus tours through this year only as evidence of the college’s devotion to the American Revolution. (Princeton is one of the rare American institutions older than its country. The university was on its sixth president by the time the ink dried on the US Constitution.) According to Martha Sandweiss, the historian who led the project, Princeton epitomizes “the paradox at the heart of American history: from the very start, liberty and slavery were intimately intertwined.”

The Library of CongressAn advertisement announcing the estate sale of Samuel Finley, then president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), including “Two negro women, a negro man, and three Negro children,” 1766

Slavery was not uncommon in New Jersey, and even once abolition began, it took generations to complete. An 1804 law granted emancipation only to New Jersey slaves born after July 4 of that year, and only after they had served what one historian has called a “term” of slavery that could last for as many as twenty-five years. One result of this gradual abolition was that many New Jersey slaveholders sold enslaved children born after that deadline to plantations out of state, which reduced the number of enslaved people in New Jersey without emancipating anyone. Another was the transition to institutions that closely resembled slavery: towns throughout the state established “poorhouse farms,” where the vagrant or indigent would be confined to work or were sometimes rented out. Businessmen traveling from New Brunswick to New York at the turn of the nineteenth century—a trip that could take the better part of three days, generally by carriage and boat—would come across “stray negroes” who could be jailed, then sold to pay jail expenses, if they failed to explain themselves sufficiently. The last child registered for gradual emancipation—a girl named Hannah, born in 1844, before legislators replaced the category with something called “apprentices for life”—remained enslaved until barely two weeks before the Confederacy’s 1865 surrender. Princeton’s entanglement with slavery, Sandweiss said when describing the project’s findings last fall, is “typical of other eighteenth-century institutions. And it makes us quintessentially and deeply American.”

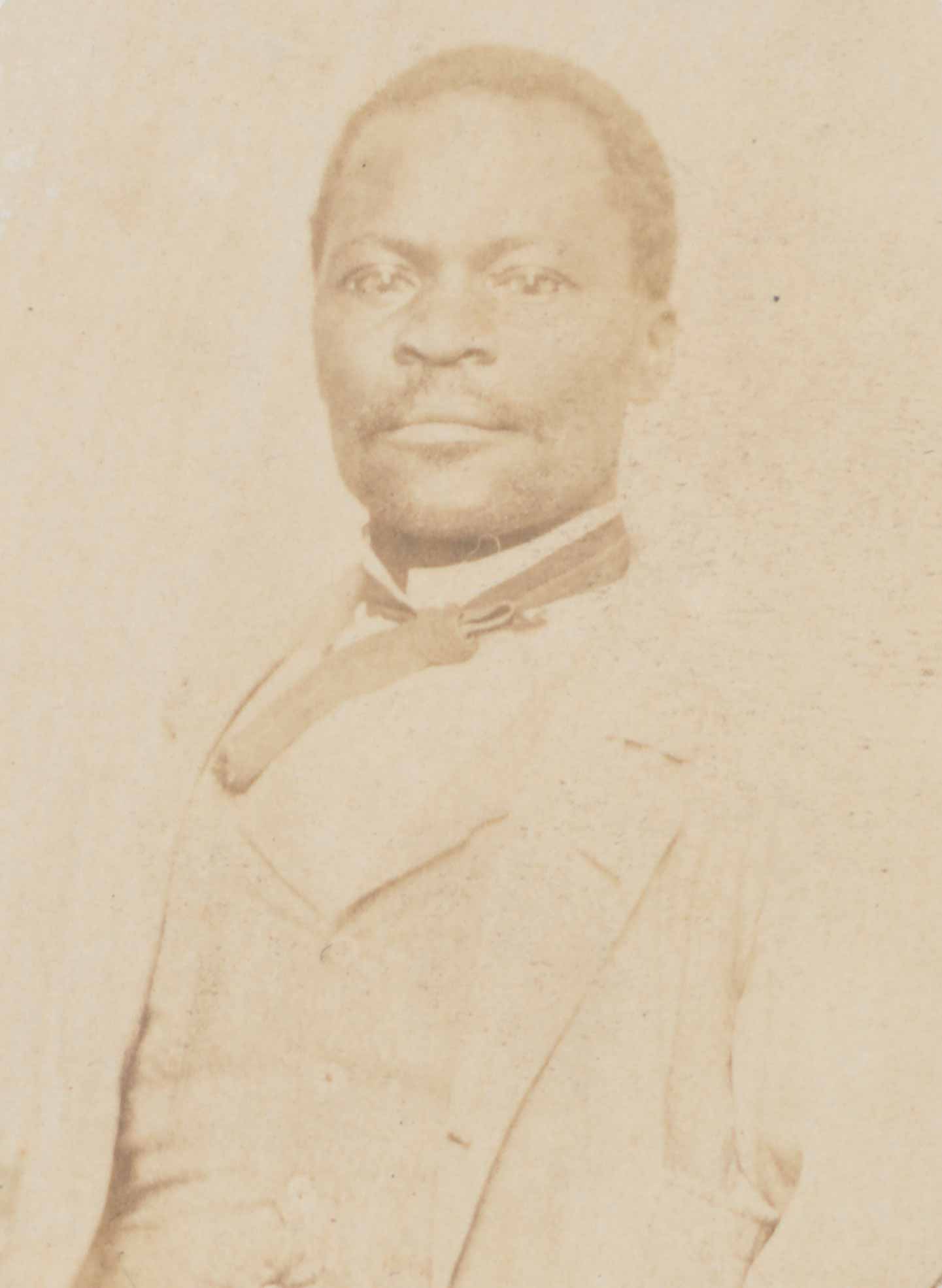

Class of 1860: Charles E. Green, box 23, Historical Photograph Collection, Princeton University LibraryJames Collins Johnson, a former fugitive slave, circa 1860; click to enlarge

Slavery and the American University

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

cont....

At its best, this wave of research demonstrates the ways in which slavery and its legacies have built the world we live in: how the ideas and institutions born in one era do not entirely cast off the forces that shaped them as they move through time. There is no evidence that Princeton University itself owned slaves, but by the early nineteenth century its main building, Nassau Hall, was adjacent to a private farm where enslaved people tended to cattle and worked in a cherry orchard; on the other side of the building, slaves worked in the taverns and other businesses on Nassau Street. Before they could enroll in courses, prospective students had to pass exams in Latin and Greek administered personally by the president; Sandweiss speculates that students arriving for their exams early on their first morning would be greeted at the president’s doorstep by “an enslaved person—the first person on campus a prospective student might meet.” As the college began to chase planter wealth, its antebellum student body grew disproportionately Southern and repeatedly clashed with Princeton’s community of free African Americans. The school’s Civil War memorial is one of the very few in the country to list the names of the war dead without noting on which side they fought—Sandweiss knew of only one other, at a boarding school—and the university began to grow to its modern size through gifts from a family fortune made by providing financial and shipping services to Cuban slave plantations until at least 1866, the year after slavery’s abolition in the United States.

The Works of John Witherspoon, D.D., Vol. VIIIPages from an address by John Witherspoon, then president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), to slaveholders in the Caribbean on behalf of the college, 1772

Yet one of the most powerful things about Princeton’s project is its recognition of where history can fall short. Sandweiss, like her colleagues at a handful of other schools, has called on other methods and genres in the service of a broader aim. Princeton reached out to the community’s schools and libraries (“Students in Princeton’s high schools will learn that there was slavery in New Jersey,” Sandweiss says), and commissioned works from artists and filmmakers. The painter and sculptor Titus Kaphar installed a piece at the site of the slave sale, facing the sycamores in the middle of Princeton’s campus, with a brief explanation of the auction for whoever walks by—an intervention in the stories Princeton tells about itself. McCarter Theatre in Princeton commissioned seven playwrights to write short plays based on documents and findings from the archives, working with archivists and historians to extrapolate details of enslaved people’s lives from what records do exist. “Historians can exercise a certain kind of imagination, but there are leaps we cannot make and be responsible to the rules of our profession,” Sandweiss says. “We cannot imagine what a nine-year-old boy thinks as he and his family are going to be put up for sale. But artists might.”

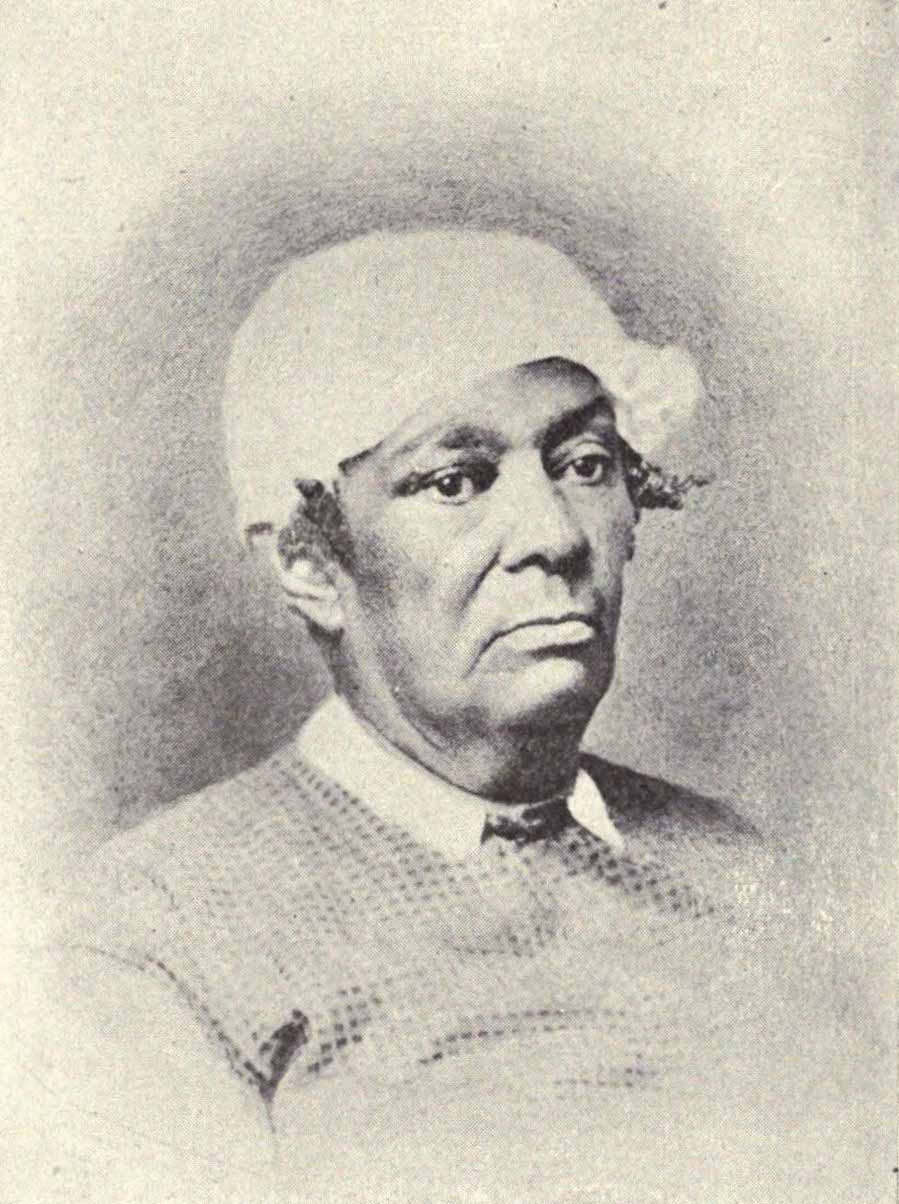

Hawaiian Mission Children's SocietyBetsey Stockton, a former slave in Princeton who worked as a missionary and teacher in Hawaii, circa 1865; click to enlarge

Emily Mann’s “Under the Liberty Trees” dramatizes the slave sale directly. Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s “Travel” draws on the lives of Betsey Stockton, a woman once owned by a Princeton president who became a missionary in Hawaii and then a teacher in Princeton’s sole public school for black children, and Cezar Trent, a free black Princeton slaveowner. The play imagines a fictional meeting between Stockton, Trent, and a lightly fictionalized Jacobs-Jenkins, who also lived in Princeton, as an undergraduate. Two other plays, by Regina Taylor and Jackie Sibblies Drury, examine the life of James Johnson, a former fugitive slave who, after a Princeton student recognized him on campus and alerted his former owners in Maryland, worked as a street vendor and campus handyman in part to repay the local woman who had purchased his freedom.

The tools of history may also be ill-suited to express the emotional force of what they uncover. More than one historian working on these projects spoke of moments when some aspect of their work unexpectedly moved them to tears. For James Campbell, it was an eighteenth-century campus abolitionist’s plea for future generations to look more closely at “this barbarous traffic,” and at the racial subjugation underpinning it, pulled off an archive shelf on a night when Campbell was trying to answer his own questions about how best to do just that. “Somebody had left a message in a bottle,” he said, sent across a sea of two hundred years. For Adam Rothman, a historian at Georgetown and a member of that university’s working group on slavery, memory, and reconciliation, it came not during his research, but when he began to push the group’s findings out into the world. In a library special collections room last spring, Rothman presented some of the baptismal records, letters, and bills of sale from the papers of the Jesuit priests who established Georgetown and its plantations. “I gave a pretty conventional academic talk to a fairly conventional academic crowd,” Rothman recounted at a conference this year. “There was a gentleman standing in the back of the room who didn’t quite fit in the mold.” He went on:

He was wearing a kind of track suit, tattoos all over his body—arms and neck. He raised his hand, and he just started talking. And he started to say that the names that he was reading on the bill of sale were names that he recognized. Names from his ancestors. And he was just breaking down, crying, talking about how—he was Catholic—how those priests, who were supposed to be shepherds of their flock, could sell those people. How they could send them to the wolves. He was having a crisis of faith, right there. He asked me, How could this happen? And what are we going to do about it? I had no answer for him.

The man’s name is Joe Brown. He had been traveling to historical societies and churches for nine years, after a difficult time sent him looking for what he calls “some strength from my ancestors.” He had visited Georgetown that day to look through one of the library’s archives and happened to pass by the special collections room after Rothman began his presentation. “I asked an attendant that was there if I was allowed to go in,” Brown says. Once he entered the room and began to listen, “I realized that Adam was talking about my family.” After a DNA test, Brown found a group of relatives living in Louisiana, where Georgetown infamously sold 272 slaves in 1838.

Encounters like this might be the most powerful result of this work—as well as the lasting networks of scholars, activists, artists, students, neighbors, descendants, and community members coalescing around them, as projects first begun in isolation have built upon one another. Their strength lies not just in a profound sense of connection with the past but, through the past, a collective grappling with the present. None of the investigations into universities’ complicity with slavery set out exactly to resolve the moral issues their discoveries would raise, but as they find their audiences, they create what one historian described as “the constituencies for different kinds of conversations.” The work of history does not always overlap cleanly with the work of politics, and the archives alone may not yield what seem like the most urgent answers. But they help sharpen the questions.

Titus Kaphar/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York/Princeton University Art MuseumTitus Kaphar’s art installation, Impressions of Liberty, which addresses the 1766 sale of six enslaved people belonging to Princeton president Samuel Finley, outside the Maclean House where the sale took place, Princeton, 2017; click to enlarge

Black Lightning

Superstar

E.D. Nixon

Edgar Daniel Nixon, an African American civil rights leader and union organizer, is remembered primarily for helping lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama from 1955 to 1956. E.D. Nixon was born to Wesley M. Nixon, a Baptist minister, and Sue Ann Chappell Nixon, a maid-cook, in Lowndes County, Alabama on July 12, 1899. Due to his mother’s death as a young boy, Nixon lived with various family members during his childhood and received little formal education.

In the early 1920s, he found a job as a Pullman sleeping car porter and was exposed to Jim Crow policies throughout his travels on the trains. In 1928 he met A. Phillip Randolph, the recently elected leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union. The union called for higher wages and better working conditions for black porters and Randolph persuaded Nixon to become a union organizer.

Nixon married his first wife Alease in 1926. They had their first and only son, E.D. Nixon, Jr. who was born in 1928. He married Arlette Nixon after Alease died in 1934.

In the early 1940s, Nixon organized the Alabama Voters League. He was responsible for leading a 750-person march on Montgomery County Municipal Court House in 1944 to challenge racist policies regarding black voting. This was the first major protest march in Montgomery since the Reconstruction era. In 1945, Nixon was elected president of the Montgomery Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and two years later, in 1947, he became the state president of the NAACP.

In the early 1950s, Nixon played a crucial role in convincing the Montgomery Police Department to hire the first African American policemen.

It was the Montgomery Bus Boycott, however, that gave Nixon national fame. On December 1, 1955, Nixon posted bail for Rosa Parks after she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white male passenger. That arrest initiated a series of events that led to the boycott. Nixon arranged for Clifford Durr, a white attorney, to represent Parks in court and then he and other Montgomery blacks organized the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). Nixon persuaded Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., a relative newcomer to the city, to become the MIA's first president.

The leaders of MIA, including Nixon, organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott in which Montgomery’s black citizens refused to ride public transportation for 381 days to protest racial discrimination. Nixon's activism prompted bus boycott opponents to bomb his home on February 1, 1956. Nixon was not there at the time.

On June 3, 1957, Nixon left the MIA to protest what he saw as the domination of the organization by middle class leaders who refused to share power with low income black men and women. Despite his prominence in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, he played no role in the Alabama civil rights struggles of the 1960s. Instead he worked as recreation director for the city's public housing projects. E.D. Nixon was given the NAACP's Walter White Award for public service in 1985.

Edgar Daniel Nixon died on February 25, 1987 in Montgomery. In 2001, to honor his work as a civil rights leader the Montgomery County Public School System named an elementary school after him.

Edgar Daniel Nixon, an African American civil rights leader and union organizer, is remembered primarily for helping lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama from 1955 to 1956. E.D. Nixon was born to Wesley M. Nixon, a Baptist minister, and Sue Ann Chappell Nixon, a maid-cook, in Lowndes County, Alabama on July 12, 1899. Due to his mother’s death as a young boy, Nixon lived with various family members during his childhood and received little formal education.

In the early 1920s, he found a job as a Pullman sleeping car porter and was exposed to Jim Crow policies throughout his travels on the trains. In 1928 he met A. Phillip Randolph, the recently elected leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union. The union called for higher wages and better working conditions for black porters and Randolph persuaded Nixon to become a union organizer.

Nixon married his first wife Alease in 1926. They had their first and only son, E.D. Nixon, Jr. who was born in 1928. He married Arlette Nixon after Alease died in 1934.

In the early 1940s, Nixon organized the Alabama Voters League. He was responsible for leading a 750-person march on Montgomery County Municipal Court House in 1944 to challenge racist policies regarding black voting. This was the first major protest march in Montgomery since the Reconstruction era. In 1945, Nixon was elected president of the Montgomery Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and two years later, in 1947, he became the state president of the NAACP.

In the early 1950s, Nixon played a crucial role in convincing the Montgomery Police Department to hire the first African American policemen.

It was the Montgomery Bus Boycott, however, that gave Nixon national fame. On December 1, 1955, Nixon posted bail for Rosa Parks after she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white male passenger. That arrest initiated a series of events that led to the boycott. Nixon arranged for Clifford Durr, a white attorney, to represent Parks in court and then he and other Montgomery blacks organized the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). Nixon persuaded Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., a relative newcomer to the city, to become the MIA's first president.

The leaders of MIA, including Nixon, organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott in which Montgomery’s black citizens refused to ride public transportation for 381 days to protest racial discrimination. Nixon's activism prompted bus boycott opponents to bomb his home on February 1, 1956. Nixon was not there at the time.

On June 3, 1957, Nixon left the MIA to protest what he saw as the domination of the organization by middle class leaders who refused to share power with low income black men and women. Despite his prominence in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, he played no role in the Alabama civil rights struggles of the 1960s. Instead he worked as recreation director for the city's public housing projects. E.D. Nixon was given the NAACP's Walter White Award for public service in 1985.

Edgar Daniel Nixon died on February 25, 1987 in Montgomery. In 2001, to honor his work as a civil rights leader the Montgomery County Public School System named an elementary school after him.

Last edited:

Black Lightning

Superstar

John Gloucester

John Gloucester, founder of the first African American Presbyterian Church in the United States, was born enslaved in Blount County, Tennessee, in 1776. Before gaining his freedom, his name was Jack, and as a believer he began converting slaves to Christianity at an early age.

Rev. Gideon Blackburn, the new Pastor at New Providence Presbyterian Church in Blount County, Tennessee, recognized the potential in Jack and after personally teaching him theology and other subjects, he purchased Jack for the sole purpose of helping him gain his freedom. Although Blackburn's 1806 petition for freedom to the Tennessee legislature was denied, Blackburn received a certificate of manumission for Jack through the local courts the same year. Upon freedom, 30 year-old Jack changed his name to John Gloucester.

Sources:

John Gloucester, founder of the first African American Presbyterian Church in the United States, was born enslaved in Blount County, Tennessee, in 1776. Before gaining his freedom, his name was Jack, and as a believer he began converting slaves to Christianity at an early age.

Rev. Gideon Blackburn, the new Pastor at New Providence Presbyterian Church in Blount County, Tennessee, recognized the potential in Jack and after personally teaching him theology and other subjects, he purchased Jack for the sole purpose of helping him gain his freedom. Although Blackburn's 1806 petition for freedom to the Tennessee legislature was denied, Blackburn received a certificate of manumission for Jack through the local courts the same year. Upon freedom, 30 year-old Jack changed his name to John Gloucester.

Sources:

Black Lightning

Superstar

Peter Salem

Peter Salem was a Patriot of the American Revolutionary War, who spent two months fighting alongside his former owners at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. Salem is credited with killing British Major John Pitcairn during the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Peter Salem was born enslaved in Framingham, Massachusetts, on October 1, 1750. He was owned by Army Captain Jeremiah Belknap and spent most of his early life working on his owner’s farm. Early in 1775, Salem was sold to a Patriot soldier, Major Lawson Buckminster, who emancipated Salem so he could enlist in his regiment of Massachusetts Minutemen.

Peter Salem was a Patriot of the American Revolutionary War, who spent two months fighting alongside his former owners at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. Salem is credited with killing British Major John Pitcairn during the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Peter Salem was born enslaved in Framingham, Massachusetts, on October 1, 1750. He was owned by Army Captain Jeremiah Belknap and spent most of his early life working on his owner’s farm. Early in 1775, Salem was sold to a Patriot soldier, Major Lawson Buckminster, who emancipated Salem so he could enlist in his regiment of Massachusetts Minutemen.

Black Lightning

Superstar

Early life

York was born in Caroline County near Ladysmith, Virginia. He, his father, his mother (Rose) and younger sister and brother (Nancy and Juba), were enslaved by the Clark family. York was William Clark's servant from boyhood, and was left to William in his father's will. He had a fiance whom he rarely saw, and likely lost contact with her after 1811 when she was sold/sent to Mississippi. It is not known if York fathered any children

Lewis and Clark Expedition

Historian Robert Betts says that the freedom York had during the Lewis and Clark expedition made resuming enslavement unbearable. After the expedition returned to the United States, every other member received money and land for their services. York asked Clark for his freedom based upon his good services during the expedition. According to one account discussed below, Clark eventually gave him his freedom.

It is shown that York had gained a little freedom while on the expedition with Lewis and Clark. It is mentioned in journals that York went on scouting trips and going to trade with villages so he saw what freedom was like while doing that. He might have also been shown respect by Clark because Clark named two geographic discoveries after him; York's Eight Islands and York's Dry Creek. Also they took a poll of where they should stay over one winter and York's opinion was recorded even though it was last. This shows that York had a taste of freedom and possibly gained some respect by the fellow travelers on the expedition. Also he was able to swim unlike some of the men that were with them on their expedition.

Honors

A statue of York, by sculptor Ed Hamilton, with plaques commemorating the Lewis and Clark Expedition and his participation in it, stands at Louisville's Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere, next to the wharf on the Ohio River. Another statue of York stands on the campus of Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Oregon. Dedicated on May 8, 2010, it does not focus on York's face, since no images of York are known to exist. Instead, it features fragments of William Clark's maps "scarred" on the statue's back.[15] Yorks Islands are an archipelago of islands in the Missouri River near Broadwater County, Montana, which were named for York by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The islands were originally named "York's 8 Islands," but have since become known as "Yorks Islands" or simply "York Island". The naming of "Yorks 8 Islands" is not found in the narrative journals of Lewis and Clark. Instead it is found in Clark's tabulations of "Creeks and Rivers," by the entry, "Yorks 8 Islands."[19] The Lewis and Clark Expedition also named another geographical feature for York, "York's Dry Creek", a tributary of the Yellowstone River, in Custer County, Montana.] This name was later abandoned, and the creek was renamed "Custer Creek".

In 2001, President Bill Clinton posthumously granted York the rank of honorary sergeant in the United States Army.

Black Lightning

Superstar

Colonel Tye

Early life and slavery

Titus Cornelius was born into slavery in Colt's Neck, Monmouth County, Province of New Jersey and originally owned by John Corlies, a Quaker. Situated along the Navesink River, near the town of Shrewsbury, Titus worked on Corlies's farm in his early life. At the onset of the American Revolution, there were about 8,200 slaves in the Province of New Jersey, second only to the Province of New York among the northern American colonies, in both the number and percentage of African-Americans. Corlies, Titus's owner, held slaves despite his denomination's increasing opposition to slavery. By the 1760s, it was Quaker practice to teach slaves how to read and write, and to free them at age 21. Yet, Corlies afforded his slaves "no learning [and was] not inclined to give them any".[attribution needed][4] Known to be hard on his slaves, Corlies severely whipped them for minor causes. Corlies kept his slaves past the age of 21, and he was one of the last slaveholders in the region. In late 1775, a delegation from the Shrewsbury Meeting of the Society of Friends approached Corlies about his treatment of his slaves. The group of Quakers disapproved of Corlies's refusal to provide his slaves an education and his lack of adherence to the 1758 Quaker edict to end slavery. Corlies responded by stating that "he has not seen it his duty to give [the slaves] their freedom".[attribution needed] Titus still managed to learn about property, wealth, commodities, and the political leanings of the families in the area. Later, in 1778, the Society of Friends revoked Corlies's membership for his unyielding refusal to emancipate his slaves.

Prelude to Revolution

In November 1775, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation offering freedom to all slaves and indentured servants who would leave American masters and join the British. Lord Dunmore's act successfully prompted conspiracy among slaves in the Atlantic region, as many African-Americans finally received incentive to display rebellious behavior.[5] The proclamation and the disruption of the war contributed to an estimated nearly 100,000 slaves to escape during the Revolution, some to join the British. Planters considered Dunmore's offer a "diabolical scheme"; it contributed to their support for the Patriot cause.

Titus Cornelius coincidentally escaped from Corlies's property the day after Dunmore's proclamation and he joined British forces. Titus observed the Quakers' unsuccessful attempts to persuade Corlies to free his slaves. His recent twenty-first birthday also compelled Titus to escape, as it marked the age that most Quakers freed their slaves.[5] Carrying only a small amount of clothing "drawn up at one end with string",[attribution needed] Titus left Corlies's property and walked towards Williamsburg, Virginia.[4] Corlies promptly placed advertisements in Pennsylvania newspapers, promising a reward of "three pounds of proclamation money" for capturing Titus

American Revolutionary War

Ethiopian Regiment service

Assuming the adopted name of "Tye", Titus enlisted in the Ethiopian Regiment. In his first experience seeing action at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778, Tye captured Captain Elisha Shepard of the Monmouth militia and brought him to his imprisonment at the Sugar House in British-occupied New York City. Fought near Freehold, New Jersey, the Battle of Monmouth proved to be indecisive militarily, but it introduced British and Patriot forces to Tye's formidability as a soldier.

Leadership of Black Brigade

Colonel Tye's knowledge of the topography of Monmouth County and his bold leadership soon made him a well-known and feared Loyalist guerrilla commander. The British paid him and his group, consisting of blacks and whites, to destabilize the region. Orchestrated by Royal Governor William Franklin, the Loyalist son of Benjamin Franklin, this plan was an act of retaliation, in response to the confiscation, of Tory property, by Patriots. When Monmouth Patriots began to swiftly hang captured Tories under the vigilante law that governed Monmouth County at the time, Franklin and other British officials felt compelled to launch their plans to raid Patriot towns. On July 15, 1779, accompanied by a Tory named, John Moody and fifty African-Americans, Tye executed a daring raid on Shrewsbury, New Jersey, during which they captured eighty cattle, twenty horses, and William Brindley and Elisha Cook, two well-known inhabitants. British officers paid Tye and his men five gold guineas for their successful raids. Tye and his fellow guerrilla fighters operated out of a forested base called Refugeetown in Sandy Hook. They often targeted wealthy, slaveholding Patriots during their assaults, which often took place at night.[4] Tye led several successful raids during the summer of 1779, seizing food and fuel, taking prisoners, and freeing many slaves.

By the winter of 1779, Colonel Tye served with the "Black Brigade", a group of twenty four, black Loyalists. Tye's group worked in tandem, with a white, Loyalist unit, known as the "Queen's Rangers", to defend British-occupied New York City. Navigating undetected into the towns of Monmouth County, Tye and his men seized cattle, forage, and plate, and returned the resources to the weakened British forces. The Black Brigade also helped to usher escaping slaves to their freedom inside British lines, and even assisted their transportation to Nova Scotia. They also raided patriot sympathizers in New Jersey, captured them, and brought them to the British in return for rewards. Due to their unjust treatment as slaves, the Black Brigade often aimed their raids at former masters and their friends.[5] Further, because the members of the Black Brigade knew the homes of Patriots from their time as slaves, the Patriots feared the Black Brigade more than the regular British army

Henry Muhlenberg, a German Lutheran pastor sent to the colonies as a missionary, commented on the formidability of the Black Brigade: "The worst is to be feared from the irregular troops whom the so-called Tories have assembled from various nationalities– for example, a regiment of Catholics, a regiment of Negroes, who are fitted for and inclined towards barbarities, are lack in human feeling and are familiar with every corner of the country." Reports that African-Americans planned massacres of whites in Elizabeth and in Somerset County inflamed the local population's fear of Tye and his men. Led by David Forman, the brigadier general of the New Jersey militia, the Monmouth County Whigs organized the Association for Retaliation to protect themselves against Tye and other Loyalist raids. Panicked white Patriots pleaded with Governor William Livingston to send assistance. For example, David Forman wrote a letter to Governor Livingston detailing the extent of Tye's attacks. Livingston responded by invoking martial law, a maneuver that only served to convince more African-Americans to flee to British-held New York. For example, twenty-nine male and female African-Americans deserted from Bergen County during this time. In response, Livingston and his officials encouraged slaveholders to remove their slaves to more remote parts of New Jersey.

On March 30, 1780, Tye and the Black Brigade captured Captain James Green and Ensign John Morris. In the same raid, Tye and his men looted and burned the home of John Russell, a Patriot known for his raids on Staten Island. Shortly thereafter, Tye and his men killed Russell and wounded his young son. Beginning in June 1780, Tye led more attacks in Monmouth County. His forces attacked and killed Joseph Murray in his home in retaliation for Murray's executions of loyalists as a vigilante. He also raided Barnes Smock, a leader of Patriot militia in Monmouth County. Tye captured twelve of Smock's supporters and destroyed his artillery. In one noteworthy raid on June 22, 1780, Tye and his men captured James Mott, the second major in the Monmouth's militia regiment, James Johnson, a captain in the Hunterdon militia, and 6 other militia men. On September 1, 1780, Tye led a small group of African-Americans and Queen's Rangers to Toms River, New Jersey, with the aim of raiding the home of Captain Joshua Huddy. Known for his swift execution of captured Loyalists, Huddy was an important target for Tye and his band. Tye briefly captured Huddy, but in surprise attack, a party of Patriots helped Huddy to escape. Huddy and a female servant had managed to resist Tye's band for two hours before the Loyalists set fire to the house. The Patriots injured Tye in the fight, firing a musketball through his wrist.

Death

Colonel Tye developed tetanus and gangrene from the wound suffered in the raid against Huddy. Tye died two days later from the infection.

Legacy

Often considered one of the most effective and respected African American soldiers of the Revolution, Tye made significant contributions to the British cause. Although never commissioned an officer by the British Army, Colonel Tye earned his honorary title as a sign of respect for his tactical and leadership skills. The British often granted such titles to other noteworthy black officers in Jamaica and other West Indian islands. The British army did not formally appoint anyone of African descent to such positions, however the Royal Navy commissioned black officers. Tye's knowledge of the swamps, rivers, and inlets in Monmouth County was integral to the British efforts in New Jersey during the war. As the commander of the Black Brigade, he led raids against the American patriots, seized supplies, and assassinated American leaders during the war.

Colonel Tye served as an example of the role of African-Americans during the Revolutionary War. Lord Dunmore's proclamation involved the African-American population in the war in a manner not yet seen. The promise of freedom compelled African-American men like Tye to join the Loyalist cause. Tye and his men captured important Patriot militiamen, launched numerous raids, and seized scarce resources from the local population. Their actions captured the attention of Governor William Livingston, who felt compelled to invoke martial law in New Jersey as a result. The actions of Tye and other former slaves provoked fear that wartime abolition would cause further dislocation and disorder in the region.Further, Tye's exploits intensified white anxieties of revolt and served to reinforce anti-abolition sentimen.

Early life and slavery

Titus Cornelius was born into slavery in Colt's Neck, Monmouth County, Province of New Jersey and originally owned by John Corlies, a Quaker. Situated along the Navesink River, near the town of Shrewsbury, Titus worked on Corlies's farm in his early life. At the onset of the American Revolution, there were about 8,200 slaves in the Province of New Jersey, second only to the Province of New York among the northern American colonies, in both the number and percentage of African-Americans. Corlies, Titus's owner, held slaves despite his denomination's increasing opposition to slavery. By the 1760s, it was Quaker practice to teach slaves how to read and write, and to free them at age 21. Yet, Corlies afforded his slaves "no learning [and was] not inclined to give them any".[attribution needed][4] Known to be hard on his slaves, Corlies severely whipped them for minor causes. Corlies kept his slaves past the age of 21, and he was one of the last slaveholders in the region. In late 1775, a delegation from the Shrewsbury Meeting of the Society of Friends approached Corlies about his treatment of his slaves. The group of Quakers disapproved of Corlies's refusal to provide his slaves an education and his lack of adherence to the 1758 Quaker edict to end slavery. Corlies responded by stating that "he has not seen it his duty to give [the slaves] their freedom".[attribution needed] Titus still managed to learn about property, wealth, commodities, and the political leanings of the families in the area. Later, in 1778, the Society of Friends revoked Corlies's membership for his unyielding refusal to emancipate his slaves.

Prelude to Revolution

In November 1775, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation offering freedom to all slaves and indentured servants who would leave American masters and join the British. Lord Dunmore's act successfully prompted conspiracy among slaves in the Atlantic region, as many African-Americans finally received incentive to display rebellious behavior.[5] The proclamation and the disruption of the war contributed to an estimated nearly 100,000 slaves to escape during the Revolution, some to join the British. Planters considered Dunmore's offer a "diabolical scheme"; it contributed to their support for the Patriot cause.

Titus Cornelius coincidentally escaped from Corlies's property the day after Dunmore's proclamation and he joined British forces. Titus observed the Quakers' unsuccessful attempts to persuade Corlies to free his slaves. His recent twenty-first birthday also compelled Titus to escape, as it marked the age that most Quakers freed their slaves.[5] Carrying only a small amount of clothing "drawn up at one end with string",[attribution needed] Titus left Corlies's property and walked towards Williamsburg, Virginia.[4] Corlies promptly placed advertisements in Pennsylvania newspapers, promising a reward of "three pounds of proclamation money" for capturing Titus

American Revolutionary War

Ethiopian Regiment service

Assuming the adopted name of "Tye", Titus enlisted in the Ethiopian Regiment. In his first experience seeing action at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778, Tye captured Captain Elisha Shepard of the Monmouth militia and brought him to his imprisonment at the Sugar House in British-occupied New York City. Fought near Freehold, New Jersey, the Battle of Monmouth proved to be indecisive militarily, but it introduced British and Patriot forces to Tye's formidability as a soldier.

Leadership of Black Brigade

Colonel Tye's knowledge of the topography of Monmouth County and his bold leadership soon made him a well-known and feared Loyalist guerrilla commander. The British paid him and his group, consisting of blacks and whites, to destabilize the region. Orchestrated by Royal Governor William Franklin, the Loyalist son of Benjamin Franklin, this plan was an act of retaliation, in response to the confiscation, of Tory property, by Patriots. When Monmouth Patriots began to swiftly hang captured Tories under the vigilante law that governed Monmouth County at the time, Franklin and other British officials felt compelled to launch their plans to raid Patriot towns. On July 15, 1779, accompanied by a Tory named, John Moody and fifty African-Americans, Tye executed a daring raid on Shrewsbury, New Jersey, during which they captured eighty cattle, twenty horses, and William Brindley and Elisha Cook, two well-known inhabitants. British officers paid Tye and his men five gold guineas for their successful raids. Tye and his fellow guerrilla fighters operated out of a forested base called Refugeetown in Sandy Hook. They often targeted wealthy, slaveholding Patriots during their assaults, which often took place at night.[4] Tye led several successful raids during the summer of 1779, seizing food and fuel, taking prisoners, and freeing many slaves.

By the winter of 1779, Colonel Tye served with the "Black Brigade", a group of twenty four, black Loyalists. Tye's group worked in tandem, with a white, Loyalist unit, known as the "Queen's Rangers", to defend British-occupied New York City. Navigating undetected into the towns of Monmouth County, Tye and his men seized cattle, forage, and plate, and returned the resources to the weakened British forces. The Black Brigade also helped to usher escaping slaves to their freedom inside British lines, and even assisted their transportation to Nova Scotia. They also raided patriot sympathizers in New Jersey, captured them, and brought them to the British in return for rewards. Due to their unjust treatment as slaves, the Black Brigade often aimed their raids at former masters and their friends.[5] Further, because the members of the Black Brigade knew the homes of Patriots from their time as slaves, the Patriots feared the Black Brigade more than the regular British army

Henry Muhlenberg, a German Lutheran pastor sent to the colonies as a missionary, commented on the formidability of the Black Brigade: "The worst is to be feared from the irregular troops whom the so-called Tories have assembled from various nationalities– for example, a regiment of Catholics, a regiment of Negroes, who are fitted for and inclined towards barbarities, are lack in human feeling and are familiar with every corner of the country." Reports that African-Americans planned massacres of whites in Elizabeth and in Somerset County inflamed the local population's fear of Tye and his men. Led by David Forman, the brigadier general of the New Jersey militia, the Monmouth County Whigs organized the Association for Retaliation to protect themselves against Tye and other Loyalist raids. Panicked white Patriots pleaded with Governor William Livingston to send assistance. For example, David Forman wrote a letter to Governor Livingston detailing the extent of Tye's attacks. Livingston responded by invoking martial law, a maneuver that only served to convince more African-Americans to flee to British-held New York. For example, twenty-nine male and female African-Americans deserted from Bergen County during this time. In response, Livingston and his officials encouraged slaveholders to remove their slaves to more remote parts of New Jersey.

On March 30, 1780, Tye and the Black Brigade captured Captain James Green and Ensign John Morris. In the same raid, Tye and his men looted and burned the home of John Russell, a Patriot known for his raids on Staten Island. Shortly thereafter, Tye and his men killed Russell and wounded his young son. Beginning in June 1780, Tye led more attacks in Monmouth County. His forces attacked and killed Joseph Murray in his home in retaliation for Murray's executions of loyalists as a vigilante. He also raided Barnes Smock, a leader of Patriot militia in Monmouth County. Tye captured twelve of Smock's supporters and destroyed his artillery. In one noteworthy raid on June 22, 1780, Tye and his men captured James Mott, the second major in the Monmouth's militia regiment, James Johnson, a captain in the Hunterdon militia, and 6 other militia men. On September 1, 1780, Tye led a small group of African-Americans and Queen's Rangers to Toms River, New Jersey, with the aim of raiding the home of Captain Joshua Huddy. Known for his swift execution of captured Loyalists, Huddy was an important target for Tye and his band. Tye briefly captured Huddy, but in surprise attack, a party of Patriots helped Huddy to escape. Huddy and a female servant had managed to resist Tye's band for two hours before the Loyalists set fire to the house. The Patriots injured Tye in the fight, firing a musketball through his wrist.

Death

Colonel Tye developed tetanus and gangrene from the wound suffered in the raid against Huddy. Tye died two days later from the infection.

Legacy

Often considered one of the most effective and respected African American soldiers of the Revolution, Tye made significant contributions to the British cause. Although never commissioned an officer by the British Army, Colonel Tye earned his honorary title as a sign of respect for his tactical and leadership skills. The British often granted such titles to other noteworthy black officers in Jamaica and other West Indian islands. The British army did not formally appoint anyone of African descent to such positions, however the Royal Navy commissioned black officers. Tye's knowledge of the swamps, rivers, and inlets in Monmouth County was integral to the British efforts in New Jersey during the war. As the commander of the Black Brigade, he led raids against the American patriots, seized supplies, and assassinated American leaders during the war.

Colonel Tye served as an example of the role of African-Americans during the Revolutionary War. Lord Dunmore's proclamation involved the African-American population in the war in a manner not yet seen. The promise of freedom compelled African-American men like Tye to join the Loyalist cause. Tye and his men captured important Patriot militiamen, launched numerous raids, and seized scarce resources from the local population. Their actions captured the attention of Governor William Livingston, who felt compelled to invoke martial law in New Jersey as a result. The actions of Tye and other former slaves provoked fear that wartime abolition would cause further dislocation and disorder in the region.Further, Tye's exploits intensified white anxieties of revolt and served to reinforce anti-abolition sentimen.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

The most commonly used phrase describing the growth of the American economy in the 1830s and 1840s was “Cotton Is King.” We think of this slogan today as describing the plantation economy of the slavery states in the Deep South, which led to the creation of “the second Middle Passage.” But it is important to understand that this was not simply a Southern phenomenon. Cotton was one of the world’s first luxury commodities, after sugar and tobacco, and was also the commodity whose production most dramatically turned millions of black human beings in the United States themselves into commodities. Cotton became the first mass consumer commodity.

Understanding both how extraordinarily profitable cotton was and how interconnected and overlapping were the economies of the cotton plantation, the Northern banking industry, New England textile factories and a huge proportion of the economy of Great Britain helps us to understand why it was something of a miracle that slavery was finally abolished in this country at all.

Let me try to break this down quickly, since it is so fascinating:

Let’s start with the value of the slave population. Steven Deyle shows that in 1860, the value of the slaves was “roughly three times greater than the total amount invested in banks,” and it was “equal to about seven times the total value of all currency in circulation in the country, three times the value of the entire livestock population, twelve times the value of the entire U.S. cotton crop and forty-eight times the total expenditure of the federal government that year.” As mentioned here in a previous column, the invention of the cotton gin greatly increased the productivity of cotton harvesting by slaves. This resulted in dramatically higher profits for planters, which in turn led to a seemingly insatiable increase in the demand for more slaves, in a savage, brutal and vicious cycle.

Now, the value of cotton: Slave-produced cotton “brought commercial ascendancy to New York City, was the driving force for territorial expansion in the Old Southwest and fostered trade between Europe and the United States,” according to Gene Dattel. In fact, cotton productivity, no doubt due to the sharecropping system that replaced slavery, remained central to the American economy for a very long time: “Cotton was the leading American export from 1803 to 1937.”

What did cotton production and slavery have to do with Great Britain? The figures are astonishing. As Dattel explains: “Britain, the most powerful nation in the world, relied on slave-produced American cotton for over 80 per cent of its essential industrial raw material. English textile mills accounted for 40 percent of Britain’s exports. One-fifth of Britain’s twenty-two million people were directly or indirectly involved with cotton textiles.”

“First cotton gin” from Harpers Weekly. 1869 illustration depicting event of some 70 years earlier by William L. Sheppard. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs division)

And, finally, New England? As Ronald Bailey shows, cotton fed the textile revolution in the United States. “In 1860, for example, New England had 52 percent of the manufacturing establishments and 75 percent of the 5.14 million spindles in operation,” he explains. The same goes for looms. In fact, Massachusetts “alone had 30 percent of all spindles, and Rhode Island another 18 percent.” Most impressively of all, “New England mills consumed 283.7 million pounds of cotton, or 67 percent of the 422.6 million pounds of cotton used by U.S. mills in 1860.” In other words, on the eve of the Civil War, New England’s economy, so fundamentally dependent upon the textile industry, was inextricably intertwined, as Bailey puts it, “to the labor of black people working as slaves in the U.S. South.”

The Role Cotton Played in the 1800s Economy | African American History Blog | The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

John Edward Bruce, also known as Bruce Grit or J. E. Bruce-Grit (February 22, 1856 – August 7, 1924)

was an American journalist, historian, writer, orator, civil rights activist and Pan-African nationalist. He was born a slave in Maryland, United States, but later during his adult life, he founded numerous newspapers along the East Coast, as well as co-founding (with Arthur Alfonso Schomburg) the Negro Society for Historical Research in New York.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Ryan Kyle Coogler

(born May 23, 1986) is an American film director and screenwriter. His first feature film, Fruitvale Station (2013), won the top audience and grand jury awards in the U.S. dramatic competition at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival.[2] He has since co-written and directed the seventh film in the Rocky film saga, Creed (2015), and the Marvel Cinematic Universe superhero film Black Panther (2018). His work has received critical acclaim and commercial success.[3] In 2013, Time named Coogler to their list of the 30 people under 30 who are changing the world.[4] He frequently collaborates with actor Michael B. Jordan, who has appeared in all of his feature films.[5]

Ryan Coogler is the New Steven Spielberg: ‘Black Panther’ Cements the Rise of Hollywood’s Commercial Auteur

From Sundance breakout to Hollywood A-lister in five years, Coogler's rapid rise speaks to a major industry shift.

Five years before he made the world’s most culturally significant blockbuster with “Black Panther,” Ryan Coogler was at the Sundance Institute’s Screenwriters Lab, workshopping his first feature “Fruitvale Station.” The five-day gathering overlapped with Martin Luther King Jr. Day; on that morning, lab coordinator Michelle Satter invited fellows to share thoughts about its significance over breakfast. Until that point, Coogler struck many other participants as a quiet, soft-spoken young man. Then he stood up.

“He gave this beautiful, deeply felt, and completely extemporaneous speech about how Dr. King’s legacy inspired him as a storyteller,” recalled David Lowery, who was then developing “Ain’t Them Bodies Saints” at the lab. (Like “Fruitvale,” it would premiere at Sundance a year later.) “It was an incredibly moving testament, both personal and all-encompassing in its scope, and we all heard the voice that has since been resonating so powerfully in Ryan’s work.”

Now Coogler has delivered Marvel and Disney the most revered Hollywood achievement of the 21st century to date, a black superhero story with an almost all-black cast — and the movie’s very existence has galvanized an oft-neglected demographic of moviegoers who at long last are getting their due. On track to grossing a record-breaking $180 million on its opening weekend, “Black Panther” speaks to a turning point in the industry’s bumpy path to diversification. Coogler’s trajectory sits at the center of this celebratory moment, but his capacity to deliver fine-tuned crowdpleasers for black audiences — along with everyone else — didn’t materialize overnight.

See More:‘Black Panther’ Review: Ryan Coogler Delivers the Best Marvel Movie So Far

By any standard, this 31-year-old Bay Area native catapulted from breakout indie talent to A-list Hollywood director on a compact timeline. Each of his movies, as well as his short films, has provided a keen window into African-American identity. By the time the profound tearjerker “Fruitvale” nabbed the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, Coogler was already developing the screenplay for “Creed,” his surprising and thoughtful reinvention of the “Rocky” franchise with Michael B. Jordan as the offspring of Apollo Creed. While shooting that project with Sylvester Stallone, Coogler got the call from Marvel about “Black Panther,” after talks with Ava DuVernay fell apart. A year later, he was tackling the dazzling saga of the regal T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) in a globe-trotting adventure that stretched from the mystical African nation of Wakanda to inner-city Oakland.

“Black Panther”

Marvel

“It’s been a weird journey for me, man,” Coogler said, sitting down in a midtown hotel as he worked through a dense promotional schedule. In person, Coogler tends to speak in slow, considered sentences interspersed with lengthy pauses for contemplation. “What’s funny is, I get that independent film was my roots, but I don’t really have roots, you know what I’m saying? Each film was its own thing, so I never calcified in terms of a certain way of making movies.”

With “Fruitvale,” he said, “my friends were producers, and we were shooting in the Bay without a lot of money. It felt like an extension of what we did in film school. ‘Creed’ felt exponentially more complex, but when I got into it, it felt the same. I guess it’d be different if I’d made three movies like ‘Fruitvale,’ then I would’ve had a way I’d be used to making movies. I never planned to make them in a certain way.”

Still, Coogler has cemented a process, one described by friends and peers as intensely collaborative with an eye for detail. His movies radiate intention; collectively, his three features form a body of work that upends expectations. “Fruitvale” is the ultimate emotional package, exploring the final day in the life of Oscar Grant and culminating with his unjust death at the hands of a police officer, but it never sags into obvious sentimentality — the movie’s loose, naturalistic style brings viewers inside the world of its protagonist, and his murder resonates with unexpected power. “Creed” achieves a similar effect with the legacy of Apollo, exhuming a character many viewers discarded as a campy sidekick years ago to reclaim his cultural significance.

Now comes “Black Panther,” which celebrates blackness as a global identity while exploring its uneasy relationship to other facets of modern culture. Notably, its villain is an Oakland-born man (Jordan) of Wakandan heritage convinced that the African nation should rule the world, while T’Challa believes in a more balanced approach to helping his people thrive.

That ideological divide harkens back to the contradictory quotes from King and Malcolm X at the end of “Do the Right Thing,” even as it percolates alongside sprawling CGI-spiced showdowns, fast cars, and spear-wielding warrior princesses. “This film is very much about identity,” Coogler said during a Q&A following a BAM screening later that week, where the movie showed as a part of a series focused on black superheroes. “I had a lot of pain inside me, due to not being able to know my ancestors, to access that wound.”

Coogler’s personalized approach to mainstream cinema, calmly juggling substance and spectacle, positions him as a next-generation Spielberg. The comparison has been applied with less accuracy before, most notoriously with M. Night Shyamalan, but in this case isn’t much of a stretch: Spielberg was on his third feature when he upended the blockbuster model with “Jaws,” establishing a new Hollywood royalty charged with satisfying massive audiences and channeling classic tropes in new ways. While DuVernay has been hailed for her role in raising the dialogue about African-American filmmaking, and her “A Wrinkle in Time” marks the first time a black woman has directed a $100-million movie, it’s Coogler who embodies what commercially viable cinema can look like in a progressive business.

“It’s a game changer for our industry,” said Charles D. King, the former WME partner whose company MACRO supports film and TV projects from people of color. King, who first connected Coogler with Stallone for “Creed” when he was still at WME, added that Coogler’s easygoing demeanor made him a natural fit for the potential chaos of a major studio production.

“Ryan’s not only being a great storyteller, he’s a leader, a coalition builder,” King said. “When you’re putting together a movie on a scope like this, with dozens of department heads and pieces you have to bring together, he’s the type of person who would know how to communicate and inspire groups of people. I’ve known him for six years and have never seen him lose his temper.”

Coogler acknowledged the potential dangers of bringing his precise style of filmmaking into the studio arena — and shrugged them off. “People did say I should be wary about working with a studio,” he said. “But I felt like I was making personal movies every time. Contractually, I didn’t have final cut — but I really did, you know what I’m saying?”

As much as he had to juggle the tricky dynamics of fast-paced action scenes, Coogler projected a confidence on set that informed his relationship to the cast, endowing the project with a sense of purpose that extended beyond the payoffs of another Marvel sensation. He spent time in Africa researching the project and used it to inform his approach to the performances.

“He spoke so clearly about accessibility and authenticity,” said Danai Gurira, the actress and playwright who plays Okaye, the head of Wakanda’s armed forces. “He was going to use the authenticity of what he’d experienced … he was going to let that pour into the film. He wanted to hit on that, and the conversations this film was going to hit on are so insanely timely.”

“Black Panther”

rest here

Ryan Coogler is the New Steven Spielberg: ‘Black Panther’ Cements the Rise of Hollywood’s Commercial Auteur

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Levi Watkins Jr.

Dr. Levi Watkins, Jr. was a cardiac surgeon who, in 1980, performed the first implantation of an automatic defibrillator into a human heart. He was also a professor of cardiac surgery and associate dean at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Watkins was born in Parsons, Kansas, but grew up in Montgomery, Alabama. He attended the First Baptist Church, and became close friends with the Pastor, Dr. Ralph David Abernathy. He later attended the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where he met Dr. Martin Luther King, who had recently begun preaching there. Inspired by King, and dismayed at the prejudices of Jim Crow Alabama, Watkins became involved in the civil rights movement. He joined the King-supervised Crusaders youth group and drove parishioners to the church in a station wagon so they could boycott the city’s segregated bus system in 1956.

Watkins entered Tennessee State University in 1962. He eventually became president of the student body, majored in biology, and graduated with honors in 1966. That May, he became the first African American admitted to the Vanderbilt School of Medicine in Nashville. Studying at Vanderbilt was a lonely, isolating experience, and when King was murdered in 1968, Watkins was still the only black student at the school. Despite the prejudice he encountered there, he in 1970 became the first African American to graduate from Vanderbilt.

Later that year Watkins moved to Baltimore, where he became the first black intern at Johns Hopkins University Medical School. Between 1973 and 1975, he studied at Harvard Medical School’s Department of Physiology, performing breakthrough research into the role of the renin angiotensin system in congestive heart failure. When he returned to Johns Hopkins in 1975, he became the first black chief resident in heart surgery at the university.

Watkins performed the first implantation of an automatic defibrillator in February 1980. Joining a team working on the device that included Michel Mirowksi, Morton Mower, and William Staewen, and assisted by Dr. Vincent Gott, the chief of cardiac surgery, Watkins performed the operation on a 57-year-old woman from California at Johns Hopkins Hospital. The defibrillator is a small, battery-powered device that detects arrhythmia in the heart and emits an electric shock to correct it. Since that operation, it has saved more than one million lives.

Watkins had also been selected to join the medical school’s admissions committee, where he focused on correcting racial inequality in the student body. He was so successful that by 1983, black students in the Hopkins Medical School had increased fivefold to 40 compared to the eight students there in 1978.

Watkins was promoted to full professor of cardiac surgery in 1990. He was awarded a medal of honor as an outstanding alumnus by the Vanderbilt school, and has been given honorary doctorates by Sojourner-Douglass College, Meharry Medical College, Spelman College, and Morgan State University. In April 2010, he was awarded the Thurgood Marshall College Fund award for excellence in medicine.

Dr. Levi Watkins, Jr. died in Baltimore, Maryland on April 18, 2015. He was 70.

Dr. Levi Watkins Jr., the first surgeon to successfully implant an automatic defibrillator in a human and a civil rights activist who helped open the doors of John Hopkins University School of Medicine to minority students, has died at the age of 70.

Watkins died April 11 from a massive heart attack and stroke, his relatives said.

"Levi was a son of the South who was birthed in the middle of segregationist America and the middle of a civil rights movement and became somebody who defied the limits of the expectations of him," said former Rep. Kweisi Mfume, who met Dr. Watkins in the 1980s on a picket line calling for better treatment of African Americans in the criminal justice system.

Watkins won acclaim in 1980, when he implanted a defibrillator in a 57-year-old female patient, a procedure that now is performed tens of thousands of times a year for patients with life-threatening episodes of ventricular fibrillation.

He became the first black chief resident of cardiac surgery at John Hopkins.

"His contributions to cardiac surgery will be legendary," said Dr. Ben Carson, a retired John Hopkins neurosurgeon.

Watkins was born in Kansas, the third of six children, but grew up in Alabama, where he got a firsthand look at the civil rights movement.

There, at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, he met the church's pastor — the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. When he grew older, Watkins became King's driver, shuttling the pastor around town.

Disheartened by the injustices he saw, Watkins threw himself into the civil rights movement,

Watkins became the first African American to graduate from Vanderbilt University in Nashville with a medical degree. It was an experience he described over the years as isolating and lonely.

After graduating from Vanderbilt, Watkins started a general surgery residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1971, where he became the first black chief resident of cardiac surgery. He left Baltimore for two years to conduct cardiac research at Harvard Medical School before returning to Johns Hopkins.

Watkins was considered a pioneer in open-heart surgical techniques and made many improvements in the defibrillator over the years, according to the university. In 1991, he became a professor of cardiac surgery and associate dean of Hopkins' medical school. He retired in 2013.

"Levi was known far and wide for his pioneering surgical work, his mentorship to so many young people, his advocacy for minorities and his service as a role model," Dr. Duke Cameron, cardiac surgeon-in-charge at Johns Hopkins hospital and professor of surgery at the school of medicine, said in a statement.

"He probably spoke at as many churches as he did at medical meetings," Cameron said.

His contributions to the medical school reached far beyond his medical work. He was a member of the admissions committee and his recruiting efforts significantly increased minority enrollment — a 400% upswing in one four-year period. He also served as a mentor and advocate once the students arrived on campus.

At Johns Hopkins, Watkins quickly noticed that there were not a lot of other African Americans on campus, aside those who worked in the cafeteria or other service jobs, his oldest sister Annie Marie Garraway said.

"He said from Day One he would do what he could to change that. Especially because so many of their patients were from the African American community," she said.

"He never forgot the humble roots where our grandparents started and was very aware of the sacrifices to get where he was," Garraway said. "He never felt he was above speaking to the person who might have been thought to have the lowest-level job."

Watkins became a personal cardiac specialist to poet Maya Angelou, whom he hosted when she came to town for checkups or speaking engagements. They had met in the mid-1970s in Alabama when both were visiting Coretta Scott King.

Mfume said Watkins was a quiet political figure who would support those officials who were committed to the idea of justice.

"He stood up, and no one could sit him down," Mfume said.

The Rev. A.C.D. Vaughn, senior pastor at Sharon Baptist Church in Baltimore, said Watkins was "symbolic of real hope" for African Americans.

"His life shows if you are willing to do the work, you could achieve what you wanted."

Dr. Levi Watkins Jr. dies at 70; cardiac surgery innovator, activist