IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Octavius Valentine Catto

Philadelphia Unveils Statue Of Black Union Army Hero

While confederate monuments are being protested across the nation, Philadelphia erects its own monument to Black Civil War hero Octavius Catto

If your Social Studies textbooks were authored in Texas, you may not have heard of Octavius Catto, a 19th century Philadelphian activist who Mayor Jim Kenney wants the nation to know. After years of lobbying that began when Kenney was a city councilman, Philadelphia finally unveiled Catto’s statue, “The Quest for Parity”, Tuesday, 6ABC News reports. This is the first African-American statue at City Hall.

“Octavius Catto was a true American hero. Like many unheralded black American heroes, he should be revered and recognized. Their lives and accomplishments should be part of the curriculum of our schools, not just during the shortest month of the year,” Mayor Kenney told the crowd gathered for the unveiling. Catto spent a relatively short life fighting for equal rights for African Americans. The Civil War veteran was known for his contributions to education, sports, and civil rights.

Catto was a freeman born in South Carolina, but his family moved to Philadelphia when he was a child. He was the valedictorian at Cheyney University (the nation’s first HBCU that was then called the Institute for Colored Youth) in 1858 and began working there as an English and math teacher. During the Civil War, he served in the Pennsylvania National Guard and recruited more Black soldiers for the Union Army. A talented athlete, he “establish[ed] Philadelphia as a major hub of the Negro Leagues” and fought to integrate the sport in the late nineteenth century. America still hasn’t caught up to Catto’s vision of universal equality, which included voting rights for African Americans. It was the latter vision that cost Catto his life. He was shot dead by “Irish-American ward bosses” on the day he saw the fruits of his activism– the first Election Day after the ratification of the 15th Amendment allowed Black men to vote. He was only 32 years old.

Monumental Man: Martyred Activist Catto at Last Memorialized by Statue in Philadelphia

At a time when historically tone-deaf monuments to Confederate leaders, slave owners, genocidal explorers and other beacons of white supremacy occupy public attention, the city of Philadelphia has erected its first monument to a Black leader in a public space. A martyred civil rights activist, educator and baseball player, Octavius Valentine Catto is one of those unsung heroes who was left out of the history books and is a perfect example of the type of figures society should honor and canonize.

The statue of Octavius Catto was unveiled on Tuesday in front of Philadelphia City Hall, nearly 146 years after his death. He was a part of history at a pivotal time for African-Americans, and yet his story resonates with the issues, challenges and struggles facing Black people today.

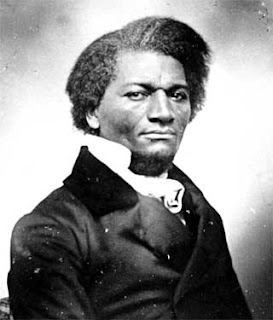

Catto was born free in 1839 in Charleston, South Carolina, and was raised in Philadelphia, attending the Institute for Colored Youth, later known as Cheyney University, where he would later become a teacher and principal. He worked with Frederick Douglass to recruit hundreds of Black soldiers to fight for the Union Army in the Civil War.

Octavius V. Catto

A leader in civil rights activism and politics, Catto fought via civil disobedience for equal access for Black people on Philadelphia’s trolley car system and played a crucial role in the passage of a Pennsylvania state law prohibiting segregation in the transit systems. He became an influential Republican Party insider and joined the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League to help secure the right to vote for Black people. Through his efforts, Pennsylvania ratified the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In addition, Catto attended the National Convention of Colored Men in Syracuse, New York, which created the National Equal Rights League.

The NERL, which selected Frederick Douglas as its president, worked toward full citizenship rights for African-Americans. Catto also held leadership positions in the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League and the State Convention of Colored People, which took place in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1865. He became a member of the Franklin Institute, a center for science education and research which had been closed to Blacks, and served in the Pennsylvania National Guard.

An athlete who played cricket and baseball, Catto founded the Philadelphia Pythians professional baseball club.

Just one year following the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870, Philadelphia had its first election in which Black people had a right to vote, on October 10, 1871. At that time, Black voters, who were Republican, faced violence and intimidation from Irish-Americans who controlled the city’s Democratic machine. On Election Day Catto was harassed by a group of Irish-Catholic men and shot to death by a man named Frank Kelly. Thousands attended the funeral of the slain leader, and because he was killed while on duty as a national Guardsman, the viewing of his body was held at the City Armory. Catto was buried in the Black-owned Lebanon Cemetery. Kelly, who eluded the authorities for over six years, stood trial and was acquitted by an all-white jury in 1877. Philadelphia’s current mayor, Jim Kenney, championed the cause of bringing the Catto statue to City Hall.

Depiction of the murder of Octavius V. Catto. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

His is the first statue built at City Hall since the memorial to merchant and department store pioneer John Wanamaker in 1923. Although the city had to wait until 2017 to have its first Black hero sculpted, other white figures of questionable merit and ill repute have stood. The Catto memorial is only yards away from the statue of the late police commissioner and mayor Frank Rizzo, known for his “law and order and “tough on crime” stance, who left a legacy of police brutality, terrorizing of the Black community and racial violence against the Black Panthers, MOVE and other political activists.

Standing at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the statue of boxer Rocky Balboa, the star of the “Rocky” movie franchise as portrayed by Sylvester Stallone. A fictional character, the Rocky statue is a popular tourist site and came years before a bronze statue to boxing legend Smokin’ Joe Frazier was unveiled in 2015.

“We shall never rest at ease, but will agitate and work, by our means and by our influence, in court and out of court, asking aid of the press, calling upon Christians to vindicate their Christianity, and the members of the law to assert the principles of the profession by granting us justice and right, until these invidious and unjust usages shall have ceased,” Catto once said. Now, Black Philadelphia honors Octavius Catto–a prominent scholar, activist and athlete, and a man who stood up for racial injustice–at a time when the community needs to draw inspiration from those forgotten heroes who helped paved the way, and paid the ultimate price for doing so.