You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Official African American Thread#2

- Thread starter Rhapscallion Démone

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Clarence Wesley "Cap" Wigington (1883-1967) was an African-American architect who grew up in Omaha, Nebraska. After winning three first prizes in charcoal, pencil, and pen and ink at an art competition during the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in 1899, Wigington went on to become a renowned architect across the Midwestern United States, at a time when African-American architects were few.[1] Wigington was the nation's first black municipal architect,[2] serving 34 years as senior designer for the City of Saint Paul, Minnesota's architectural office when the city had an ambitious building program.[3] Sixty of his buildings still stand in St. Paul, with several recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. Wigington's architectural legacy is one of the most significant bodies of work by an African-American architect.[4]

Clarence Wesley Wigington was born in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1883, but his family soon moved to Omaha, where he was raised in North Omaha's Walnut Hill neighborhood. After graduating from Omaha High School at the age of 15[citation needed], Wigington left an Omaha art school in 1902 to work for Thomas R. Kimball, then president of the American Institute of Architects. After six years he started his own office. In 1910 Wigington was listed by the U.S. Census as one of only 59 African-American architects, artists and draftsmen in the country.[4] While in Omaha, Wigington designed the Broomfield Rowhouse, Zion Baptist Church, and the second St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church building, along with several other single and multiple family dwellings.[5]

After marrying Viola Williams, Wigington received his first public commission, to design a small brick potato chip factory in Sheridan, Wyoming. He ran the establishment for several years.[6]

It was in Saint Paul, Minnesota where Wigington created a national reputation. He moved there in 1914 and by 1917 was promoted to the position of senior architectural designer for the City of St. Paul. During the 1920s and '30s, Wigington designed most of the Saint Paul Public Schools buildings, as well as golf clubhouses, fire stations, park buildings, airports for the city. Other Wigington structures include the Highland Park Tower, the Holman Field Administration Building and the Harriet Island Pavilion, all now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, as well as the Roy Wilkins Auditorium. Wigington also designed monumental ice palaces for the St. Paul Winter Carnival in the 1930s and '40s.[7]

Wigington was among the 13 founders of the Sterling Club, a social club for railroad porters, bellboys, waiters, drivers and other black men. He founded the Home Guards of Minnesota, an all-black militia established in 1918 when racial segregation prohibited his entry into the Minnesota National Guard during World War I. As the leader of that group, he was given the rank of captain, from which the nickname "Cap" was derived.[8]

After retiring from the City of St. Paul in 1949, Wigington began a private architectural practice in California. Soon after moving to Kansas City, Missouri in 1967, he died on July 7.[9]

Notable designs

As senior architect for the city, Wigington designed schools, fire stations, park structures and municipal buildings. Aside from his work in Omaha, Wigington also designed the building which originally hosted the North Carolina State University at Durham.[10]

Nearly 60 Wigington-designed buildings still stand in St. Paul. They include the notable Highland Park Clubhouse, Cleveland High School, Randolph Heights Elementary School, and the downtown St. Paul Police Station, in addition to the Palm House and the Zoological Building at the Como Park Zoo.[11]

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Black Minnesotans made headlines across the nation even before the state was admitted to the Union in 1858, and any number of black explorers, advocates, teachers and preachers played crucial roles in launching many of the state’s earliest institutions.

Some now have buildings named after them; others are lesser-known.

February is Black History Month, a fitting time to recognize black trailblazers who helped open doors for future generations of Minnesotans.

From the state’s first black millionaire to its first black lawmaker, this list — by no means exhaustive — is meant to highlight a few men and women whose names you probably don’t hear as often as Prince or Gordon Park

16 trailblazing black Minnesotans you should know more about – Twin Cities

.

.

.

Minnesota's African American history begins with pioneers who trapped, traded and developed lasting relationships with the Indian nations. In the 1790s, Pierre Bongo (Bonga or Bungo), a free black fur trader, came to the territory and married an Ojibwe woman. Their son, George Bonga, born in 1802, was Minnesota's first recorded African American birth. George became a fur trader, too, as well as an important interpreter who helped negotiate agreements between the Ojibwe and the U.S.

From these beginnings shaped by economic opportunity and relative freedom, Minnesota's African American history was forged. This tour highlights Saint Paul's history as a point of entry for African Americans who came seeking new beginnings and new paradigms from which to create new lives. Here are just some of the stories of individuals and institutions that helped to shape Minnesota's capital city.

Tour | African American Heritage: Points of Entry | Saint Paul Historical

.

.

.

Morrill Hall takeover Victory Day - January 15, 1969

Early Establishment

The Department of African American & African Studies at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities began in 1969 with the establishment of the Department of Afro-American Studies. As occurred on many other university campuses across the country at that time, politically conscious and activist-oriented Black University of Minnesota students demanded that the study of Black people in the United States and the worldwide African diaspora be taught in a systematic way.

Furthermore, students demanded that these new studies be housed independently. The department's creation, therefore, arose largely from the will of Minnesota students. In turn, the department strives to serve Minnesota students and the larger community in the present generation and in generations to come.

Foundations

Although the department came into existence in a dynamic political and social environment, its intellectual and institutional foundations were laid well over a century earlier by such scholars as W.E.B. DuBois, Anna Julia Cooper, George Washington Williams, Maria Stewart, William Wells Brown, and Carter G. Woodson. Like these pioneering individuals and their works, the Department of African American and African Studies has been strongly interdisciplinary, and committed to studying all peoples of African descent, including their historical and cultural connections.

Global Scope

In this spirit, the department integrated the University's African Studies Council in 1975 and changed its name to the Department of Afro-American and African Studies. The goal of the council was to make African studies visible at Minnesota and to support the research of its members. In 1992, a single major in African American and African studies was created.

With the Africa and the African diaspora track, the department has truly become global in scope, focusing on all peoples of African descent as they have built their lives and communities throughout the world.

History

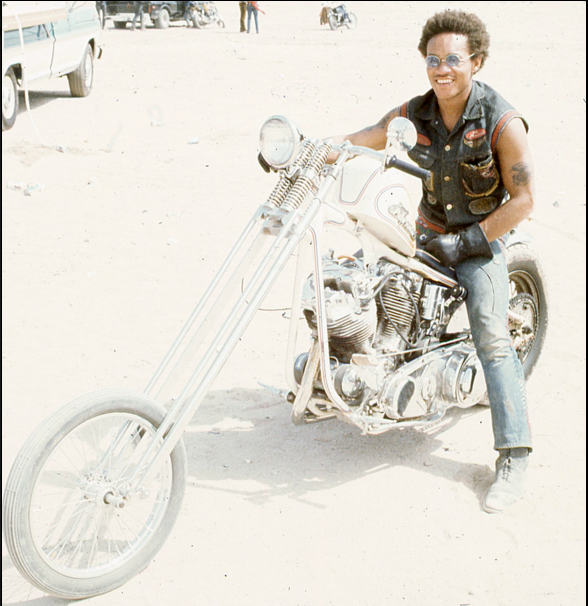

Behind The Motorcycles In 'Easy Rider,' A Long-Obscured Story

On Oct. 18, the Calabasas, Calif.-based auction house Profiles In History will auction off what it says is the last authentic motorcycle used in the filming of 1969's Easy Rider, and what some consider the most famous motorcycle in the world.

Peter Fonda, who played Wyatt in the Dennis Hopper-directed film, rode the so-called "Captain America" bike, named for its distinctive American flag color scheme and known for its sharply-angled long front end.

The bike currently for sale was partially destroyed in the film's finale, the auction house says, and then rebuilt by actor Dan Haggerty. (The three other bikes used in the production were stolen prior to the film's release.)

According to Brian Chanes, acquisitions manager for the auction house, the bike's estimated value is between $1 million and $1.2 million.

But despite the bike's fame, the history of the creation of the bikes used in Easy Rider has for many years been largely unknown. And the man who designed and coordinated the building of the motorcycles, Clifford Vaughs, says he and the other bike builders have not received proper credit for their work.

Choppers: 'Quintessentially American'

The motorcycles used in Easy Rider were not simply rolled out of a showroom and in front of the camera. They were "choppers," crafted by hand.

Choppers are "a type of customized motorcycle usually defined by a stretched out wheel-base, and pulled back handlebars, and a sissy bar, and a wild paint job," says Paul d'Orleans, the author of the upcoming book, The Chopper: The Real Story. "It's a quintessentially American folk art form."

The "Captain America" bike is an unmistakable and legendary chopper, and has made an enormous impact on the world of motorcycling.

The bikes in Easy Rider, d'Orleans says, "did more to popularize choppers around the world than any other film or any other motorcycle. I mean, suddenly people were building choppers in Czechoslovakia, or Russia, or China, or Japan."

Whose hands turned the wrenches? Who welded the steel? Most of the time, d'Orleans says, choppers are associated with their builders, "because they are an artistic creation. And curiously, the Easy Rider bikes were never associated with any particular builder."

In fact, two documentaries about the production of Easy Rider — 1995's Born To Be Wild and 1999's Easy Rider: Shaking The Cage — never name the men who designed and built the choppers.

Finding The Builders

In bits and pieces, the story behind the Easy Rider choppers began to emerge publicly, and identified two African-American bike builders: Clifford "Soney" Vaughs, who designed the bikes, and Ben Hardy, a prominent chopper-builder in Los Angeles, who worked on their construction.

Conflicting Tales

More than 45 years after the production of Easy Rider, it's difficult to sort out the exact timeline of the film's creation, and the various responsibilities of the people involved. Several of the key figures involved with the film have died, including director Dennis Hopper and credited screenwriter Terry Southern.

The history of the production has also been particularly messy.

"The whole thing has been like a Rashomon experience," producer Bill Hayward, who died in 2008, told the filmmakers who made Easy Rider: Shaking The Cage. "The whole movie, the whole production ... everyone's got an entirely different story."

Clifford Vaughs, for his part, says he acted as an associate producer early on in the film's production. By his account, he designed the bikes himself, and is responsible for the distinctive look of the "Captain America" bike. He says he also worked with Ben Hardy to purchase engines at a Los Angeles Police Department auction, and coordinated the building of the bikes.

Peter Fonda, meanwhile, has said that he himself played a greater role in the design and construction of the bikes.

"I built the motorcycles that I rode and Dennis rode," Fonda told WHYY's Fresh Air in 2007. "I bought four of them from Los Angeles Police Department. I love the political incorrectness of that ... And five black guys from Watts helped me build these."

A publicist for Fonda said that he was unavailable for comment for this story.

But in 2009, Dennis Hopper recorded an audio commentary track for the Criterion Collection release of the film, in which he says Vaughs "built the bikes, built the chopper."

Larry Marcus is a mechanic who lived with Vaughs at the time, and worked on the choppers and the early film production. "Cliff really came up with the design for both motorcycles," Marcus said in a phone interview.

According to the press release announcing the current auction, the Captain America bike "was designed and built by two African-American chopper builders — Cliff Vaughs and Ben Hardy — following design cues provided by Peter Fonda himself."

Raw Feelings

Vaughs says he and others were fired and replaced early on in the film's production, following the chaotic shoot at Mardi Gras in New Orleans. As a result, his name never appears in the credits. And while the film went on to become one of the top-grossing films of 1969 and a cultural touchstone, the name Clifford Vaughs has remained largely unknown.

Clifford Vaughs, seen here in Colombia circa 2000, says he has never watched Easy Rider, despite the fact that he designed the bikes used in the film.

Courtesy of Clifford Vaughs

"I'm a little miffed about this, but there's nothing I can do," Vaughs says of the story, though he makes sure to note that he only spent about a month working on Easy Rider, out of a "long and illustrious life."

But he says the absence of black characters in the film is troubling. In the 1960s, Vaughs belonged to an integrated motorcycle club known as The Chosen Few. That multi-ethnic reality was not reflected on screen.

"Why is it that we have a film about America and there are no negroes?" he says.

Vaughs says the omission of his own name and that of other African-Americans in the retelling of the Easy Rider story is conspicuous.

"Those bikes, when we talk about iconic, they are definitely iconic," he says. "But yet, the participation of blacks ... completely suppressed, completely suppressed. And I say suppressed, because no one talks about it."

To this day, Vaughs has never watched Easy Rider. When asked why, he responds simply, "What for?"

A Million-Dollar Icon

Brian Chanes, of Profiles In History, says it's common for the men and women who actually build iconic props to go unrecognized. He handles some of the most famous props ever seen on screen, like Wolverine's claws from X-Men or the whip used in theIndiana Jones films.

"The guys that were back there doing the welding, the guys that are doing the set building, that are really masters of their craft," Chanes says, "they don't get the notoriety, unfortunately."

Now, nearly five decades after the release of Easy Rider, Vaughs says he's unconcerned about whether he's mentioned in connection with the auction.

"I'm really not worried about getting any credit for this, because I know what I did," Vaughs says. "People who were close to me were there in the yard when I was building those bikes."

On Oct. 18, the Calabasas, Calif.-based auction house Profiles In History will auction off what it says is the last authentic motorcycle used in the filming of 1969's Easy Rider, and what some consider the most famous motorcycle in the world.

Peter Fonda, who played Wyatt in the Dennis Hopper-directed film, rode the so-called "Captain America" bike, named for its distinctive American flag color scheme and known for its sharply-angled long front end.

The bike currently for sale was partially destroyed in the film's finale, the auction house says, and then rebuilt by actor Dan Haggerty. (The three other bikes used in the production were stolen prior to the film's release.)

According to Brian Chanes, acquisitions manager for the auction house, the bike's estimated value is between $1 million and $1.2 million.

But despite the bike's fame, the history of the creation of the bikes used in Easy Rider has for many years been largely unknown. And the man who designed and coordinated the building of the motorcycles, Clifford Vaughs, says he and the other bike builders have not received proper credit for their work.

Choppers: 'Quintessentially American'

The motorcycles used in Easy Rider were not simply rolled out of a showroom and in front of the camera. They were "choppers," crafted by hand.

Choppers are "a type of customized motorcycle usually defined by a stretched out wheel-base, and pulled back handlebars, and a sissy bar, and a wild paint job," says Paul d'Orleans, the author of the upcoming book, The Chopper: The Real Story. "It's a quintessentially American folk art form."

The "Captain America" bike is an unmistakable and legendary chopper, and has made an enormous impact on the world of motorcycling.

The bikes in Easy Rider, d'Orleans says, "did more to popularize choppers around the world than any other film or any other motorcycle. I mean, suddenly people were building choppers in Czechoslovakia, or Russia, or China, or Japan."

Whose hands turned the wrenches? Who welded the steel? Most of the time, d'Orleans says, choppers are associated with their builders, "because they are an artistic creation. And curiously, the Easy Rider bikes were never associated with any particular builder."

In fact, two documentaries about the production of Easy Rider — 1995's Born To Be Wild and 1999's Easy Rider: Shaking The Cage — never name the men who designed and built the choppers.

Finding The Builders

In bits and pieces, the story behind the Easy Rider choppers began to emerge publicly, and identified two African-American bike builders: Clifford "Soney" Vaughs, who designed the bikes, and Ben Hardy, a prominent chopper-builder in Los Angeles, who worked on their construction.

Conflicting Tales

More than 45 years after the production of Easy Rider, it's difficult to sort out the exact timeline of the film's creation, and the various responsibilities of the people involved. Several of the key figures involved with the film have died, including director Dennis Hopper and credited screenwriter Terry Southern.

The history of the production has also been particularly messy.

"The whole thing has been like a Rashomon experience," producer Bill Hayward, who died in 2008, told the filmmakers who made Easy Rider: Shaking The Cage. "The whole movie, the whole production ... everyone's got an entirely different story."

Clifford Vaughs, for his part, says he acted as an associate producer early on in the film's production. By his account, he designed the bikes himself, and is responsible for the distinctive look of the "Captain America" bike. He says he also worked with Ben Hardy to purchase engines at a Los Angeles Police Department auction, and coordinated the building of the bikes.

Peter Fonda, meanwhile, has said that he himself played a greater role in the design and construction of the bikes.

"I built the motorcycles that I rode and Dennis rode," Fonda told WHYY's Fresh Air in 2007. "I bought four of them from Los Angeles Police Department. I love the political incorrectness of that ... And five black guys from Watts helped me build these."

A publicist for Fonda said that he was unavailable for comment for this story.

But in 2009, Dennis Hopper recorded an audio commentary track for the Criterion Collection release of the film, in which he says Vaughs "built the bikes, built the chopper."

Larry Marcus is a mechanic who lived with Vaughs at the time, and worked on the choppers and the early film production. "Cliff really came up with the design for both motorcycles," Marcus said in a phone interview.

According to the press release announcing the current auction, the Captain America bike "was designed and built by two African-American chopper builders — Cliff Vaughs and Ben Hardy — following design cues provided by Peter Fonda himself."

Raw Feelings

Vaughs says he and others were fired and replaced early on in the film's production, following the chaotic shoot at Mardi Gras in New Orleans. As a result, his name never appears in the credits. And while the film went on to become one of the top-grossing films of 1969 and a cultural touchstone, the name Clifford Vaughs has remained largely unknown.

Clifford Vaughs, seen here in Colombia circa 2000, says he has never watched Easy Rider, despite the fact that he designed the bikes used in the film.

Courtesy of Clifford Vaughs

"I'm a little miffed about this, but there's nothing I can do," Vaughs says of the story, though he makes sure to note that he only spent about a month working on Easy Rider, out of a "long and illustrious life."

But he says the absence of black characters in the film is troubling. In the 1960s, Vaughs belonged to an integrated motorcycle club known as The Chosen Few. That multi-ethnic reality was not reflected on screen.

"Why is it that we have a film about America and there are no negroes?" he says.

Vaughs says the omission of his own name and that of other African-Americans in the retelling of the Easy Rider story is conspicuous.

"Those bikes, when we talk about iconic, they are definitely iconic," he says. "But yet, the participation of blacks ... completely suppressed, completely suppressed. And I say suppressed, because no one talks about it."

To this day, Vaughs has never watched Easy Rider. When asked why, he responds simply, "What for?"

A Million-Dollar Icon

Brian Chanes, of Profiles In History, says it's common for the men and women who actually build iconic props to go unrecognized. He handles some of the most famous props ever seen on screen, like Wolverine's claws from X-Men or the whip used in theIndiana Jones films.

"The guys that were back there doing the welding, the guys that are doing the set building, that are really masters of their craft," Chanes says, "they don't get the notoriety, unfortunately."

Now, nearly five decades after the release of Easy Rider, Vaughs says he's unconcerned about whether he's mentioned in connection with the auction.

"I'm really not worried about getting any credit for this, because I know what I did," Vaughs says. "People who were close to me were there in the yard when I was building those bikes."

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

These Summer Resorts Once Offered African Americans Sun, Jazz, Food, and Relaxation During the Jim Crow Era

http://www.edwardianpromenade.com/african-american/african-american-resorts-during-the-jim-crow-era/

Photo courtesy of Highland Beach Historical Collection.

When the dog days of summer come around, the prospect of relaxing and playing on beautiful beaches is highly anticipated. The laws of “Jim Crow” (the colloquial name for the dizzying array of prohibitions and restrictions placed on black and white interaction from roughly 1896 to 1954/1964) meant that African Americans were often barred from enjoying their summers in the same manner as European Americans. In a slightly ironic twist, before Jim Crow laws hardened race relations and created a permanent color line, according to Andrew W. Kahrl in The Land Was Ours, distinguished African Americans “purchased cottages and established close-knit summer colonies in many of the popular summer destinations in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic states, including, among others, Saratoga, New York; Cape May, New Jersey; and Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.” 1 There was also a significant year-round population of African Americans at popular Gilded Age summer resorts, as evidenced by the Gilded Age Newport in Color website. From the 1890s to the 1960s, the resorts that sprang up along the coastlines of the United States provided a haven against racism and humiliation, created multi-generational memories, and tell a story of how landscapes and leisure can be used to combat oppression!

Highland Beach, Maryland

Twin Oaks, Frederick Douglass summer home [courtesy of Bohl Architects]

It was the sudden hardening of the color line that influenced Charles Douglass, youngest son of Frederick Douglass, to found Highland Beach in 1893. Charles and his wife Fannie were barred from vacationing on a Chesapeake Bay resort and as they walked along a shoreline, they came across a black-owned farm. The owner sold them forty acres and Douglass divided the land into lots, which he sold to friends. “Twin Oaks,” the Queen Anne house Douglass built for his father, who died before its completion, is now The Frederick Douglass Museum and Cultural Center. Other nearby African American enclaves included the villages of Arundel-on-the-Bay and Oyster Harbor.

Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard (Massachusetts)

Shearer Cottage, Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard [courtesy of CBS News]

The African American presence on Martha’s Vineyard stretches back to the mid-18th century, according to Jill Nelson in her family memoir/history book Finding Martha’s Vineyard. The area known as Oak Bluffs was originally a Methodist revival camp; by the turn-of-the-century, African American Yankees were a significant presence in this corner of the island, whether they were business-owners or pleasure-seekers. The official period of African American leisure began in 1903 when Charles Shearer, a teacher born enslaved in 1854, purchased a cottage near the Baptist church where he and his family worshiped. His wife Henrietta started a laundry to supplement the family’s income, which she ran until her death in 1917. The Shearer daughters converted the former laundry into a guest house and inn for African American vacationers–Shearer Cottage–which still operates today.

Sag Harbor, Long Island (New York)

Historic plaque marking entrance into Sag Harbor

As with Martha’s Vineyard, the African American presence on Long Island stretches back to the days of slavery. The Zion A.M.E. Church established in 1840 was even a stop on the Underground Railroad! They heyday of Sag Harbor began in the late 1920s, when prominent African American New Yorkers (re)discovered the comforts of the coast during the hot summer months. 2 The communities of Azurest, Sag Harbor, and Ninevah flourished between 1948 and 1955, when Maud Terry of Queens, NYC purchased property in Azurest and sold lots to friends. Other wealthy African Americans soon followed, and soon this became the hidden secret of the Hamptons!

Idlewild, Michigan

Idlewild Athletic Field, ca 1910s

Beautiful Idlewild. Black Eden. Those were some of the names bestowed upon this incredible summer resort in the wilds of Western Michigan. Founded in 1912 by white investors who sold lots to the black elite in Chicago and Detroit (and later from all parts of the United States), it quickly became the place to be for doctors, lawyers, and the brightest stars of the 20th century, from Cab Calloway to Dinah Washington during its heyday in the 1940s-60s. The average Idlewilders took advantage of the lush beach and the gorgeous forest, taking part in hunting and fishing, as well as athletics.

American Beach, Florida

Group of African American women at American Beach, FL

As stated on the plaque marking American Beach as a registered historic site, this stretch of Florida coastline was established by Florida’s richest African American, Abraham Lincoln Lewis, a co-founder of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company. He intended the beach to be a leisure spot for executives and employees of the life insurance company, and from the 1920s to the 1960s it was yet another hot spot for the 20th century’s famous and renown, from Zora Neale Hurston to Joe Louis. After its near destruction by a hurricane in 1964, Lewis’s great-granddaughter, MaVynee Betsch, returned to fight for recognition of the beach’s importance to Florida history and African American history.

http://www.edwardianpromenade.com/african-american/african-american-resorts-during-the-jim-crow-era/

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Shearer Cottage's History on Martha's Vineyard

Shearer Cottage - Family owned and operated with pride since 1903

.

.

Since opening its doors in 1903, the Shearer Cottage has remained one of Martha's Vineyard's landmark institutions and an integral component of the rich history of African American life, commerce and culture in Oak Bluffs. The Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture is honored to preserve and share the history of Shearer Cottage on the National Mall for generations to come." Kevin Strait, Museum Historian.

Charles Shearer, the son of a white slave master and his enslaved black woman, was born into slavery on a farm in Spanish Oaks, Appomattox County, Virginia, on January 10, 1854. He kept to himself and spent much of the time in the surrounding woods. His days were filled with hunting and fishing, skills he learned from Native Americans who lived nearby.

Near the end of the Civil War, as Union soldiers approached his plantation, Master Shearer, the slave owner, prepared to move his slaves, money, and valuables. Charles openly declared that he was going to join the Union Army. Charles was beaten and chained in the barn, until the master was ready to move his belongings to safety. Hastily packing up to leave the area, the Master either forgot that Charles was chained in the barn or left him on purpose. The union soldiers later found Charles and permitted him to travel with them. Charles' hunting and fishing skills proved very helpful in providing food for the Union Troops.

Harry T. Burleigh with guests

at Shearer circa 1920

Over the years things went well for Charles. After the Civil War, Charles lived in Lynchburg, Virginia and worked as a laborer, before attending Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Hampton, Virginia. He graduated from Hampton Institute in 1880. Charles married Henrietta Merchant, a woman of African, white and Native American heritage from Lynchburg. Henrietta was born free to free parents, Madison and Elizabeth George Merchant, who were married in 1843 and had ten children. Henrietta also attended Hampton Institute and later served as one of Hampton's matrons. Charles taught at Hampton Institute and public schools in areas around Lynchburg, Virginia. Henrietta was also a school teacher in Lynchburg, Virginia area.

In the late 1800's, Charles and Henrietta moved North in search of a better, freer life for themselves and their children. They purchased a home and raised their family in Everett, Massachusetts, near Boston. Charles pursued a career in the hospitality industry, serving as headwaiter at two of Boston's famous hotels, Young's Hotel and the Parker House. Charles prospered. In 1893, Charles joined Boston's historic Tremont Temple Baptist Church, the first integrated church in America, from which he was later buried in 1934.

Charles Shearer with family

and guests at Shearer in 1918

Charles was a profoundly religious man who deeply appreciated the education he received at Hampton. He credited his success in life to his education and his religious conviction. A staunch Baptist, Charles often visited Oak Bluffs, then called Cottage City, on Martha's Vineyard to attend religious revivals. Charles and Henrietta grew to love the Island and purchased their first Island property in the late 1800's. Charles and Henrietta eventually sold this property. On August 28, 1903, they purchased their home overlooking the Baptist Temple Park, where Shearer Cottage now stands. Every year, Charles and Henrietta would close their winter home in Everett from the middle of June until the middle of September and move their family to their Cottage City home on Martha's Vineyard.

Sandridge Family

Guests at Shearer Cottage circa 1909

In order to help support her family's summers on Martha's Vineyard, Henrietta built a one-story, open structure known as the "Long House" beside their home and started a laundry business. She hired several Island women and specialized in the fancywork of fluting the elaborate petticoats worn in that era. An entrepreneur, Henrietta provided pick-up and delivery service for the laundry with her horse and wagon.

In 1912, Charles and Henrietta built a twelve-room home on their property overlooking the Baptist Temple Park. It was at this time that they opened a summer inn, Shearer Cottage, which was operated in conjunction with the laundry. Shearer Cottage catered to African Americans who, at that time, were not welcome as guests at other Island establishments. Henrietta's horse and wagon were now used to transport guests.

Sadie Shearer Ashburn

Innkeeper

After Henrietta's death in 1917, the laundry was closed. Charles and his two daughters, Sadie and Lily, converted the Long House into several additional rooms for their inn. When Lily died prematurely, Sadie, under Charles' guidance, continued to pursue their dream and worked passionately to build Shearer Cottage's reputation for fine food and warm hospitality.

Shearer Cottage thrived. On any given day, the dining room was filled with fifty or more guests, all enjoying delicious breakfasts and dinners cooked by Aunt Sadie (Shearer Ashburn), Uncle Robby (Merchant) and Uncle Benny (Ashburn). Nearby, black-owned homes were often called upon to supply rooms forShearer's overflow of guests. Indeed, many of the black homeowners on the Island have said that their presence here today is due to their family's earlier association with Shearer Cottage.

Adam Clayton Powell with Shearer Family and guests at Shearer Cottage

circa 1931

Shearer Cottage had a roster of black guests, many of whom are nationally known. These guests included the talented singer and actress, Ethel Waters; Paul Robeson, performer and activist; Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., one day to become US Congressman, in his mid-teens through adulthood, with his father, the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., pastor of Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church; Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, acknowledged as the firstAfrican-American psychiatrist and his wife, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, well-known sculptor; singer, Roland B. Hayes; William H. Lewis, a Bostonian, who was the first African American appointed to the post of Assistant Attorney General in the Justice Department by President Taft; Henry Robbins, the Boston court stenographer who recorded the testimony at the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti; composer and arranger, Harry T. Burleigh, who preserved the oral spirituals by putting them into print; Madam CJ Walker, hair care entrepreneur and first female to become a millionaire by her own achievements (black or white); and Lillian Evanti, acclaimed as the first African American female professional opera singer.

Shearer Cottage guests

Oak Bluffs Beach circa 1920

Commodores

1972 Walker-Araujo Wedding

More recently, Lionel Richie and the Commodores, who were managed by Benny Ashburn, Jr. (a third generation Shearer), stayed here during several summers, developing their act and playing at local clubs. The Commodores provided lively entertainment at a family wedding held here for a fourth generation Shearer, JoAnn Walker.

Shearer Family

Walker-Araujo wedding

Over the years, Shearer's charter was not only to provide comfort and good times for our guests, but also to make a significant contribution to the social and economic growth of the Island's African American community. We have provided employment for many black youth who needed work to support their education. The Cottagers, Inc., a philanthropic organization of African American women who owned homes in Oak Bluffs, and the Martha's Vineyard Chapter of the NAACP held their initial meetings at Shearer Cottage. Many fund-raisers and social events have also been held here.

Over the years, several of our family members have met their spouses on Martha's Vineyard, some actually at Shearer Cottage. Lily was the first Shearer to both meet and marry her husband, Lincoln G. Pope, Sr., on Martha's Vineyard. Lincoln was a frequent guest at Shearer Cottage with his father, Atty. James W. Pope of Boston. James W. Pope married Mary Bigelow in Danville, Virginia, where they were both born. Atty. Pope came North and graduated from Boston Universty Law School. He practiced law in Boston and lived in the Beacon Hill section of Boston, when it flourished as an African American community. Atty. Pope was the second African American to serve on the Boston City Council, appointed by Mayor Prince in the 1880's. These early relationships of our family have resulted in six generations of the Shearer family enjoying the good life on Martha's Vineyard.

Van Allen Family at Shearer Cottage

4th, 5th and 6th Generation Shearers on Martha's Vineyard

Liz, Doris and Miriam

3rd generation Shearers

at Shearer Cottage

We believe that Charles and Henrietta Shearer exhibited keen wisdom and foresight when they bought their property overlooking the Baptist Temple Park in 1903, and later established Shearer Cottage as a guesthouse. In appreciation and honor of their contribution to our family, we've worked tirelessly to preserve their legacy and maintain the Shearer property which was renovated in recent years, combining the twelve original guestrooms into six studios.

In 1997, Shearer Cottage was dedicated as the first landmark on the African American Heritage Trail of Martha's Vineyard. A plaque embedded in a rock near our cottage's front walk marks this honor.

Shearer Cottage - Family owned and operated with pride since 1903

.

.

African Americans of Martha's Vineyard have an epic history. From the days when slaves toiled away in the fresh New England air, through abolition and Reconstruction and continuing into recent years, African Americans have fought arduously to preserve a vibrant culture here. Discover how the Vineyard became a sanctuary for slaves during the Civil War and how many blacks first came to the island as indentured servants. Read tales of the Shearer Cottage, a popular vacation destination for prominent blacks from Harry T. Burleigh to Scott Joplin, and how Martin Luther King Jr. vacationed here as well. Venture through the Vineyard with local tour guide Thomas Dresser and learn about people such as Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates and President Barack Obama, who return to the Vineyard for respite from a demanding world.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

People of African heritage have lived in Rhode Island since the 17th century. The first Africans were brought to Rhode Island as part of the transatlantic maritime trade known as the Triangle Trade. Traders made rum in Rhode Island using sugar cane harvested in the Caribbean; the rum was then used to purchase African men, women, and children who were sold into slavery. Between 1700-1800, Rhode Island merchants sponsored approximately 1,000 slaving voyages, bringing over 100,000 Africans to America. While many were sold to plantation owners in the southern colonies, some were kept in Rhode Island as indentured servants or slaves. By the 1770s Rhode Island had the greatest population of slaves per capita in New England.

The history of the African American experience in Rhode Island goes well beyond slavery, however. Rhode Island was the first state to create an explicitly non-white military regiment during the American Revolution. The 1st Rhode Island Regiment, also known as “The Black Regiment,” was comprised of African American and Native American men. It served in several battles including the decisive Battle of Yorktown in 1781. During the Civil War, Rhode Island was one of the first states to propose a voluntary regiment comprised entirely of African American soldiers. Rhode Island’s African American residents were also civically engaged, actively petitioning the General Assembly in their pursuit of equal rights in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Preserving Our History, Ensuring Our Future

As one of the oldest African Heritage organizations in the country, the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society has recorded, retained and interpreted these historical facts and preserved the documents and artifacts of African-American and African descendant’s history and accomplishments in Rhode Island.

Our primary mission is the preservation of African Diaspora descendant’s historical artifacts – books, art, papers and images, as well as facilitating the interpretation efforts by those seeking to enlighten others about our heritage.

The origins of the American Civil Rights Movement began right here in Rhode Island...

Among the many "Firsts"

- Enslaved and Free Africans enlisted in the Revolutionary forces and served in the Rhode Island 1st Regiment; participating in several major battles, including the Battle of Rhode Island and Yorktown.

- In 1780, free Africans established their own self-help organization, the Free African Union Society in Newport, Rhode Island.

- Africans in Rhode Island would establish one of the nation’s earliest free African schools in 1808 and later after the Civil War would promote the integration of all public schools in Rhode Island.

https://riblackheritagesociety.wildapricot.org/

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

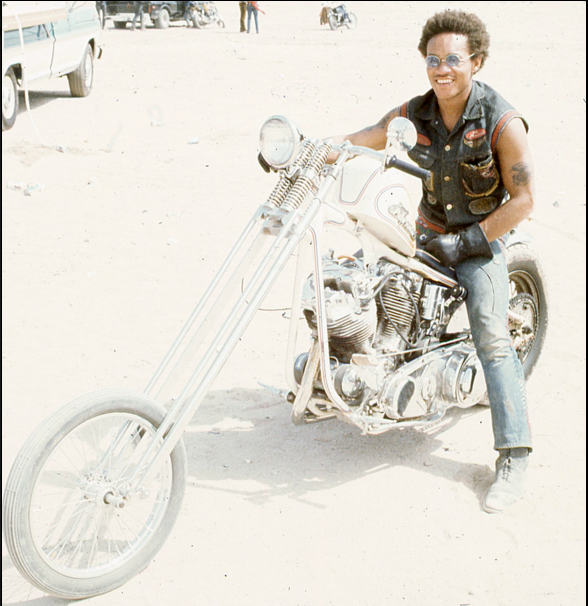

Thomas Downing

Downing's Oyster House

Before New York was called the Big Apple, it could have been called the Big Oyster. New York was famous for its oysters. And Thomas Downing, a free black man, owned the most famous oyster house of all. Bankers, politicians, stockbrokers, lawyers, businessmen, and socialites flocked to Downing’s Oyster House to eat raw, fried, or stewed oysters, oyster pie, fish with oyster sauce, or poached turkey stuffed with oysters. As the crowd of power brokers ate and made deals under the chandeliers, Thomas’s son George lead escaping slaves to the basement. There they were safe from the “blackbirders,” or bounty hunters, who were roaming the streets in search of runaways.

From 1825 to 1860, Thomas, and his son George T. Downing were part of the Underground Railroad to Canada and freedom. They were also leaders in the growing abolitionist movement. In 1836, Thomas helped found the all-black United Anti-Slavery Society of the City of New York. The next year he began petitioning New York State for equal suffrage for black men. He took one petition after another to Albany. "If one petition failed, another would be presented," he said. When not a single high school in the city would accept African American students, he helped found the first schools that would accept them. According to his son, Thomas Downing was an "extremely active" man who "knew not tire."

When Thomas Downing died on April 10, 1866, the New York Chamber of Commerce closed for the day out of respect.

Born into slavery in Virginia, Thomas Downing escaped north with his family and settled in New York City. He was a prominent leader in the black community, an early member of the African Society for Mutual Relief, a vestryman at St. Philip's, a promoter of education for black youth, and a fighter for black civil rights in the city.

In addition, Downing ran an oyster house on Broad Street. Because of its proximity to the Customs House, the port, banks, the Merchant exchange, and other important businesses, Downing counted some of New York’s most powerful men among his customers. It was said that he often passed messages back and forth between customers at different tables and that people then assumed that he wielded influence at the highest level of city government. As a result, scores of office seekers flocked to his restaurant.

When Downing died in 1866, hundreds of people—both black and white—attended his funeral.

.

.

.

How Thomas Downing became the black Oyster King of New York

http://play.publicradio.org/website...ents/2018/03/16/20180316_thomasdowning_64.mp3

click^

Oysters are often seen as a luxury food now, but throughout much of early American history they were so abundant that people from all classes regularly ate them. In coastal cities, you could have them on the street or in dingy bars for practically nothing. In late 1800s New York, a man named Thomas Downing built an empire out of an oyster bar. But here's the thing: he was a black man doing this during the era of slavery. Joanne Hyppolite, curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, shared Downing's story with Francis Lam. If their discussion makes you hungry for oysters, satisfy your craving with our recipe for Classic Creamy Oyster Stew.

= = = = = = = =

Francis Lam: Can you tell us about Thomas Downing, who he was and how he made his fortune in oysters?

Joanne Hyppolite: Thomas Downing was a restaurateur, a caterer, and an abolitionist. He was many things, but he’s most well-known for his oyster restaurant called Thomas Downing’s Oyster House in New York City that was established during the 19th century.

FL: Where did Downing come from? How did he become an oysterman?

JH: Thomas Downing was an African-American man. His parents were enslaved people who were set free by their Virginia slave masters. He grew up a free man on Chincoteague Island, which is on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. His family owned property on the island, and their lifestyle revolved around clamming, digging, raking oysters, and fishing. That was his family’s everyday livelihood.

FL: How did he come to New York?

JH: He followed the troops north out of Virginia after the War of 1812 and spent about seven years in Philadelphia where he ran an oyster bar. So, he moved from raking oysters to working in an oyster bar. And then in 1819, he shows up in the New York City census listed as an oysterman. This was an occupation that many African-American men held in New York. He would have gone out on a boat or a schooner and helped harvest some of the oysters from the many beds in New York City’s waters and brought them back, and either sold them to the various marketplaces that then sold them to restaurants or would peddle them on the streets. We’re not exactly sure, but he was definitely harvesting them at that period of time.

Joanne Hyppolite

Photo provided by Smithsonian Institution

FL: Do we know how he goes from there to having an extraordinarily successful restaurant?

JH: By the mid-1820s, we know he’s opened an oyster refractory – that’s what they’re called at that time – or an oyster cellar; they’re called cellars because you actually go down the stairs to enter these spaces. This is another occupation that a number of African-Americans had. He wasn’t the only African man who owned an oyster cellar, but he quickly distinguished himself for having a cellar like no other. He operated two properties that were adjoined to each other on Broad Street, and that gave him an expansive footprint. These other cellars were known as rough and tumble places with dim lights and a crowd. You were never sure if you were safe with your goods in these establishments. But Thomas Downing had a large dining area with curtains and fine carpet. He was known for having a chandelier in his space – this was considered fine dining. And his clientele were largely white men, men of means, merchants, bankers, Wall Street officials and newspapermen.

FL: His place became the watering hole for the elite, right? That was their spot.

JH: Yes, that’s where he really distinguished himself. He owned perhaps the best-known oyster restaurant in New York City – compared to any white or black person at that time – and it was the place to be for visiting dignitaries, travelers from different countries, merchants, and where men of means would bring their wives to eat.

FL: Is that unusual at that time?

JH: It is unusual because the place had to be respectable. That is what distinguished his establishment from all the other oyster cellars. You want to bring them to a place where a lady’s sensibilities are not going to be disturbed, right?

FL: This is interesting because we have to put ourselves in the mindset of the 1800s. Today if we think of an oyster restaurant, we automatically assume it to be nice. Oysters are expensive, they’re an elite food, but back then, oysters were an everyday food. They were an everyman food. And for him to lavish this kind of care, attention and luxury onto it was unique.

JH: Oysters were incredibly inexpensive back then. They were eaten by all classes. They were so plentiful that for about six cents, you could get a dozen. And when Thomas Downing enters this market, he finds a way to distinguish himself by making it a place where – as the upper class are looking for a sense of refinement and class in places where they dine – he finds his niche.

FL: And he was incredibly successful. He owned the place that the elite came to, and I heard that when he passed away, the New York City Chamber of Commerce came to his funeral. Is that true?

JH: Yes. They closed for the day for his funeral. He certainly gained a lot of social and political capital because of the clientele that he served. These men of means had connections throughout New York City. They seemed to have quite a bit of respect for him, and when Thomas Downing occasionally got into trouble, he could pull these connections that he had to back him up and support him.

For instance, there are stories of other African-American oystermen who owned more ordinary cellars. And currency during that period of time wasn’t always stable. There were fake levels of currencies, fake money, that people would use to pay for their food, and you could spot them right away. None of that seemed to happen at Thomas Downing’s oyster house. He knew that he could get the backup of his own clientele to support him if he was calling a particular currency of a customer into question, whereas other African-American men didn’t have that kind of support and often had to deal with the fact that they were being swindled.

FL: He seemed to be very important to different communities. Not only the elite community, but also to people fleeing enslavement. Is it correct that his place was a stop on the Underground Railroad?

JH: It was. On the one hand, here’s Thomas dining with this exclusive white clientele at his restaurant; it’s only for white diners. And on the other hand, he is this significant community figure and activist in the African-American community. He harbored refugees, slaves, and slaves on-the-run in the cellars.

After New York had abolished slavery in 1837, he was also well-known for helping found the Committee of Thirteen – an organization that was working to protect free people from being kidnapped and being sold back into the South, which we now know from the story of Solomon Northup in 12 Years a Slave.

FL: Let me pull this back a little bit. You’re a curator in the Cultural Expressions gallery of the museum, and Thomas Downing’s story isn’t the only place in your galleries where oysters appear. Why does that food hold prominence in the story of the African-American experience?

JH: Oysters help us interpret identity and historical circumstances. There are several circumstances where oysters show up throughout our 13 permanent exhibitions at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. One of the most poignant is in the Slavery and Freedom Exhibition. There are displays of oyster shells that were used by enslaved children to eat on Edisto Island, South Carolina – a waterside African-American community.

There’s a moment when encountering these oyster shells that you realize the visual disparity between enslaved people and free people – the fact that they would have to use discarded remnants of things as utensils, as opposed to knives and forks that people of better means would have access to.

https://www.splendidtable.org/story/how-thomas-downing-became-black-oyster-king-new-york

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

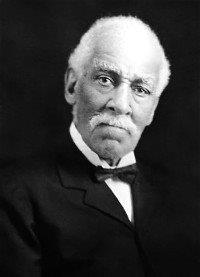

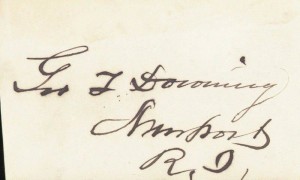

George Thomas Downing (seated front and center)

George T. Downing (December 30, 1819 – July 21, 1903) was an abolitionist and activist for African-American civil rights while building a successful career as a restaurateur in New York city; Newport, Rhode Island; and Washington, DC. His father had been an oyster seller and caterer in Philadelphia and New York City, building a business that attracted wealthy white clients. From the 1830s until the end of slavery, Downing was active in the Underground Railroad, using his restaurant as a rest station for refugees on the move. He built a summer season business in Newport, and made it his home. For more than 10 years, he worked to integrate Rhode Island public schools. During the American Civil War (1861-1865), Downing helped recruit African-American soldiers.

After the war Downing moved to Washington, DC, where for a dozen years he ran the Refectory for the House of Representatives. He was a prominent member in the Colored Conventions Movement and worked to join the efforts of women's rights and black rights. He became close to senator Charles Sumner and was with the legislator when he died. Late in his life he returned to Rhode Island, where he continued as a community leader and civil rights activist.

followed his father into the restaurant business. The elder Downing owned the fabled "Downing's Oyster House" in New York City. George T. Downing first opened a restaurant in New York in 1842, then a branch of his father's restaurant in Newport, Rhode Island in 1846, and later a catering business in Providence in 1850. With his father's support, George T. Downing opened the Sea-Girt House in Newport in 1855. Frederick Douglass described its opulent furnishings, "The entire front of the house is capable of being thrown into one spacious saloon, unfolding the connecting doors, and is beautifully furnished with rich Brussels carpeting. The chairs are of rosewood, covered with heavy satin brocade. Expensive lace curtains descend from the ceiling and window cornices." The Sea-Girt House was valued at $30,000. When arson destroyed the restaurant in 1860, Downing built a commercial real estate block on the site. After the Civil War ended, Downing operated a restaurant in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. for twelve years and continued to invest in real estate into the late 1880s.

George T. Downing was born in New York City to Thomas and Rebecca Downing. He attended schools on Orange and Mulberry streets, was home-schooled in his teens, and attended Hamilton College in upstate New York. In 1841, he married Serena Leanora DeGrasse, sister of Dr. John Van Surly DeGrasse (John Van Surly DeGrasse was a commissioned physician with the Union Army during the American Civil War and was the first black to be admitted to a United states medical society). The younger Downings made their home in Newport.

.

.

.

George T. Downing: Rhode Island’s Most Prominent African American Leader

In Rhode Island, slavery was placed on the road to extinction on March 1, 1784, when the General Assembly passed a gradual manumission act making any black born to a slave mother after that date free. Those who were slaves at that time had to be manumitted by their masters. Five such slaves were listed in the federal census of 1840, and not until the implementation of the state constitution of 1843 was slavery banned outright in Rhode Island. Free blacks with real estate could vote until 1822, when they were deprived of suffrage by statute. This restriction was erased by the constitution of 1843, in part to reward blacks for their support of the prevailing Law and Order government.

With blacks politically impotent, socially ostracized, educationally segregated during the nineteenth century, and many enslaved during the eighteenth century, it is understandable that very few black leaders emerged in Rhode Island up to the antebellum era. George Thomas Downing was one notable exception.

George T. Downing (Rhode Island Black Heritage Society Collection)

Downing was born in New York City on December 30, 1819. His father, Thomas, was a native of coastal Virginia, and his mother, Rebecca West, came from Philadelphia. George, the eldest child, had three brothers and a sister. He was fortunate in that his father established a very upscale and successful New York City restaurant, whose patrons included many of the prominent businessmen and politicians of the metropolis. This success allowed George to attend private school, as well as the Mulberry Street School, where he met several young boys who would soon become vocal abolitionists, like George himself. When he was only fourteen, George and his black schoolmates—James McCune Smith, Henry Garnet, Alexander Crummel and Charles and Patrick Benson—formed a literary society and also discussed racial issues in America. At one of their meetings, they agreed not to celebrate the Fourth of July because it was “a perfect mockery” for African Americans.

George displayed such intellectual and leadership potential that his father sent him to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, where he met and married Serena Leanora de Grasse, the daughter of a German mother and a father from India. Upon his return from Clinton, he joined with his father not only in the food business but alsoin the business of promoting racial justice. Both became active in the Underground Railroad, personally helping several fugitive slaves escape to freedom, and they lobbied the New York legislature to grant equal suffrage to blacks. Then, George struck out on his own.

In 1846, he came to Newport, a town that had a sizable black community, to replicate his father’s oyster-house restaurant. This enterprise proved successful in a town that had begun to emerge as a fashionable summer resort and which was attracting some of his father’s New York patrons. Downing wasted little time expanding his operations. In 1850, he moved temporarily to Providence, where he established a catering business for that city’s polite society. Then he turned his attention again to Newport, and in 1854–55, with some financing from his father, he built his impressive Sea Girt House on South Touro Street (now part of Bellevue Avenue), nearly opposite the Newport Tower. The multistory Sea Girt House included his residence, a restaurant, his catering business and “accommodations for gentlemen boarders.” A suspicious fire destroyed the elegant building in 1860, but Downing was able to recover $40,000 of insurance proceeds to rebuild a larger structure on the site, which came to be called the Downing Block. During the Civil War, he rented its upper floor to the temporarily relocated U.S. Naval Academy as an infirmary.

Autograph of George T. Downing of Newport (Private Collector)

Downing’s business success, remarkable as it was, would not confer on him the status as the state’s greatest African American leader in its history, but his successful campaigns against slavery and school desegregation in Rhode Island do earn him that distinction. He vigorously opposed the African colonization plan supported by Thomas Hazard, but he assisted the efforts of local abolitionists, such as Arnold and Elizabeth Buffum, and national leaders of this movement, including U.S. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and ex-slave and famed orator Frederick Douglass. Although somewhat of a black elitist, Downing regarded himself as evidence of a black person’s ability to succeed and prosper if afforded education and the equal opportunity to do so.

In his quest for human rights, Downing was most uniquely associated with the desegregation of Rhode Island’s public schools, a campaign he commenced in 1855 with the support of Senator Sumner. By 1857, he had begun to take bold public action, launching a lobbying campaign, which he personally financed, against segregated education. Among other arguments, Downing appealed to the white leadership of the state by reminding them not only of the heroics of Rhode Island’s black regiment during the Revolutionary War but also of the assistance that blacks had rendered to the victorious Law and Order Party during the Dorr Rebellion. Such rhetoric did not sit well with Rhode Island’s Irish Catholics, but constitutional restrictions on their suffrage kept those residents of the state politically impotent. During the Civil War, Downing served as a recruiter for the black Massachusetts Fifth Cavalry.

Downing’s desegregation campaign had some near misses, but it took the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 to overcome the resistance of such communities as Providence, Bristol and Downing’s own Newport. Downing’s oft-repeated argument was that all race distinctions stemmed from slavery, and thus they must die with slavery. In 1866, eleven years after Downing first strategized with Sumner, the General Assembly, with little debate, overwhelmingly voted to outlaw separate schools and ended the era of legal educational segregation in Rhode Island.

Downing continued his racial-equality crusade in the decades following the Civil War. In 1866 he was selected, along with Frederick Douglass, by a convention of black leaders to meet with President Andrew Johnson at the White House to press him for legislation to enforce voting by blacks nationwide, including in the South. Downing read a short address to Johnson at the February 7 meeting, but the racist president rejected the request. Downing’s effort attracted national attention, including a Memphis, Tennessee newspaper editor who charged that black Americans and their white allies intended “to raise ten thousand dollars” to finance the Washington lobbying efforts “of Geo[rge] Downing (******).” In 1869, he helped to form the Colored National Labor Union because of the refusal of the all-white National Labor Union to admit blacks. By the late 1870s, he had become disenchanted with the Republican Party for abandoning Reconstruction and criticized what he called “the blind adhesion of the colored people to one party.” He failed, however, in three attempts to secure election as a Newport Democrat to the Rhode Island General Assembly, leaving the honor of becoming the state’s first African American legislator to the Reverend Mahlon Van Horne, a Newport Republican, who was elected to the House for three consecutive one-year terms, beginning in 1885.

Downing’s most visible job mixed his two passions: food and politics. For twelve years, from 1865 to 1877, the outspoken Downing was in charge of the café dining room of the U.S. House of Representatives in Washington, D.C., giving him the opportunity to influence and lobby policymakers. One salutary project on which he worked was the passage in 1873 of an equal-opportunity public accommodations law for the District of Columbia. Two years after leaving his post in Washington, he retired from his Newport business.

George Downing died at his Newport home on July 21, 1903, surrounded by his several children, one of whom, Serena, wrote his brief biography in 1910. At his passing, the Boston Globe called him “the foremost colored man in the country” and praised his efforts on behalf of liberty and equality for all Americans. He was elected to the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 2003.

[Banner Image: Interior view of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1866. George T. Downing was in charge of the café dining room for House members from 1865 to 1877 (Library of Congress)]

http://smallstatebighistory.com/geo...lands-most-prominent-african-american-leader/

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Free African Union Society

.

.

.

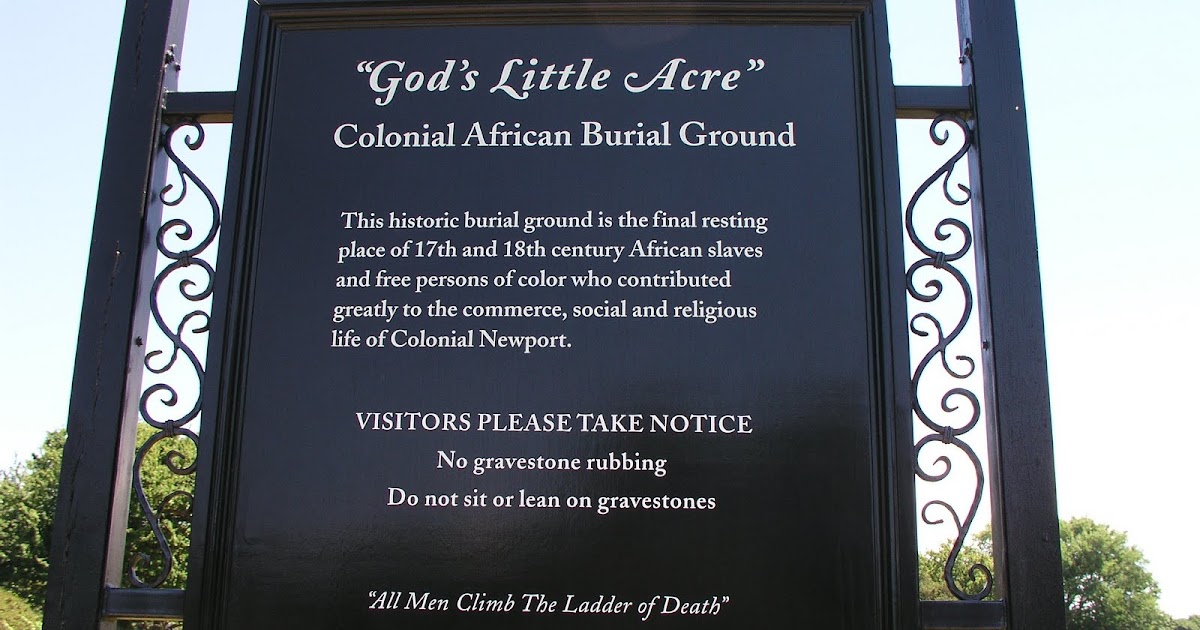

Most people when they hear the word slave think of a plantation in the south but slavery was a lot closer to home. This film tells short narratives of enslaved and free Africans in colonial Rhode Island using 18thc carved burial markers from 'God's Little Acre' in the Common Burying Ground in Newport. The camera follows Keith Stokes as he tells the stories of the contributions these early Newporters made, including Dutchess Quamino the Pastry Queen of Rhode Island and Pompe Stevens the first African-American artist. The film score is "Crooked Shanks", period music attributed to Newport Gardner, a free African who composed and taught music.

The Free African Union Society, founded in 1780 in Newport, Rhode Island, was America’s first African benevolent society. Founders and early members included Prince Amy, Lincoln Elliot, Bristol Yamma, Zingo Stevens and Newport Gardner.[1]

Background

Although Rhode Island had abolished African slavery in 1652, this law was not enforced;[2][3] By 1750,[3] Rhode Island had more slaves per capita than any other New England state.[4][2] Enslaved blacks worked as seamen, farm laborers, and domestic servants.[4] It was not until the Rhode Island General Assembly passed the Gradual Emancipation Act in March 1784 that slavery in Rhode Island was gradually outlawed.[2] Still, even after this time, Newport, as a busy port city, remained a center of the U.S. slave trade until at least 1807.[4]

Since many sources of welfare were controlled by whites, free blacks across the early United States created their own mutual aid societies. These societies offered cultural centers, spiritual assistance, and financial resources to their members.[5] The Free African Union Society was the first mutual aid society for blacks in the United States,[1] and similar societies formed throughout the Northeast during the next thirty years,[5] including Philadelphia's Free African Society in 1787.

History

The Free African Union Society of Newport was established on November 10, 1780 by Newport Gardner and Pompe (Zingo) Stevens.[6] The purpose was to assist the poor and sick, and to show mainstream white society that blacks could be responsible citizens.[6] They provided members with proper burials, cared for widows and orphans, and promoted the cause of abolition.[6] They also kept basic records of blacks in the community, and hired young enslaved black apprentices in hopes of helping them purchase their freedom.[5]

At least 85 members of the Free African Union Society between 1787 and 1810 have been identified by name.[7]

In 1824, the society changed its name to Colored Union Church and Society. [5]

Legacy

Newport today is home to a large African-American burying ground called "God's Little Acre."[6] It may be home to the largest and oldest surviving collection of burial markers of enslaved and free Africans from the time period.[6]

Background: Mutual aid societies were created by free blacks in the early period of the United States as a way of mitigating difficult times since avenues of welfare were often segregated and controlled by whites. The societies also acted as cultural centers of local communities in conjunction with churches. Membership had spiritual, moral, and philosophical components which complimented the practical benefits of financial assistance when illness and death struck the family. Most mutual aid societies at this time were short-lived and not always well-documented, but the evidence is clear that such groups existed and contributed positively to the free black and slave community.

Introduction: In 1780, The African Union Society (AUS) was created in Newport, Rhode Island. While most blacks from Rhode Island were free by 1807, strong prejudice and oppression were present before and after that date. The AUS developed partly in response to these difficulties, as well as a forum for black cultural discussion. The society is considered one of the first formal organizations founded by free blacks in the United States, although similar societies would form over the next thirty years throughout the Northeast.

Development and Activities: Some of the difficulties faced by free blacks of Rhode Island at this time included recording births, deaths, and marriages of their community, and on this premise the AUS was created. It is not surprising that this marginalized group could depend only on themselves to document family and communal life in these basic ways; blacks were segregated in churches, kept out of public schools, denied employment, and even separated from whites in cemeteries. The society provided this documentation service to free blacks and slaves.

Newport Gardner’s original name was Occramar Mirycoo before being taken from Africa. In addition to his work with the AUS, he taught Western music, developed the ability to speak English, French, and African languages, and helped organize early religious meetings in homes like that of Peter Bours shown here

Former slaves, including Newport Gardner and Pompe (Zingo) Stevens, were two of the leaders in creating the African Union Society. By providing the basic record-keeping services previously mentioned, the society hoped to encourage a strong family structure for all blacks in Newport. Additionally, the AUS took on young black apprentices in hopes of creating a pathway to freedom for them. One of the ways Gardner was able to purchase his freedom was through trade work, and he naturally believed in its value to lift up others.

For its members, the African Union Society provided the typical benefits of a mutual aid society, a buffer from the effects of illness and death in the family. Beyond the local welfare of blacks, the organization made contact with free blacks in a number of surrounding communities, hoping that expanded membership would lead to greater advancement of the race overall. They also pooled financial resources to provide loans and facilitated black purchase of property.

Some of its members were born in Africa and felt a strong connection to their home continent, and the African Union Society were early leaders in the efforts for emigration to the home continent. Reportedly, Gardner and seventy others were interested in making a new home free of Euro-American economic and political control.1 This idea would come to fruition only decades later in 1825 when Gardner arrived in Africa with a small group. He died shortly after completing the trip.

The greatest difficulty of seeking emigration or colonization in Africa is demonstrated by a letter from Anthony Taylor, the AUS president in 1787, to the federal government. Taylor explains that they write for want of money and to make sure they can claim the African land for us and our heirs.2 Interestingly enough, American ideals were present in the discussion of what a new homeland would be like. In a letter to Philadelphians, it was suggested that each emigrated settler might have a share of private property, elect their officials, have freedom of religion, and the right to bear arms. Many African societies had a shared concept of property and did not elect leaders.

One example of the society’s role in black cultural matters was its strict dress codes for member funerals developed from 1790-1794. On a basic level, this ties into the goal of the society to preserve the dignity of black family life. Some historians have speculated that the public nature of funerals, marked by a high level of formality, could have also acted as a demonstration to whites in the community of blacks’ equality. Unfortunately, free blacks may have used white funeral styles instead of African rituals, showing the pervasive nature of cultural oppression.

Even in death the race line was often maintained throughout the country. As the place where Newport’s people of color went after they died, God’s Little Acre has become an important resource for scholars interested in race in the colonies

In 1809, a female counterpart to the AUS, the African Female Benevolent Society, was created. The group focused on needs of the black Newport community in a less conditional way in clothing and educating many underprivileged children. While it is unlikely women were given a voting role in mutual aid efforts previously, there is no documentation that the new society was created in protest. Many in the new society were related to African Union Society members.

The constraints of segregation at that time are a likely cause for the diminishing of the group’s prominence near the turn of the century. Another key development was the shift in focus from mutual benefits to the organizing of a group more religious in nature. Within three years of the society’s founding, Gardner and membership had already made some adjustments to become more religious in nature, and the moral standards established for the group were based on Christian principles.

By 1824, the African Union Society completed its evolution and took up the new name Colored Union Church and Society. It became the first separate black church in Newport, and it followed the example of similar groups like the Free African Society. In fact, the creation of an independent church may have been made earlier if it was not for Samuel Hopkins, a theologian who rejected slavery. Hopkins created the First Congregational Church of which slaveholders were banned and some blacks were given full membership in Newport. He preached until his death in 1803 and was well known by AUS members, many who attended his church.

Conclusion: The Colored Union Church was one of the first churches with a solely black administration and congregation. It hoped to even unite blacks who had different denominational backgrounds. In 1859, it became the United Congregational Church and has continued as a part of the Newport community to the present day. The African Union Society, living up to its name, was a significant effort by free blacks to disassociate from the oppressive nature of the early Northeastern United States while maintaining their love of God, family, and community.

.

.

.

Most people when they hear the word slave think of a plantation in the south but slavery was a lot closer to home. This film tells short narratives of enslaved and free Africans in colonial Rhode Island using 18thc carved burial markers from 'God's Little Acre' in the Common Burying Ground in Newport. The camera follows Keith Stokes as he tells the stories of the contributions these early Newporters made, including Dutchess Quamino the Pastry Queen of Rhode Island and Pompe Stevens the first African-American artist. The film score is "Crooked Shanks", period music attributed to Newport Gardner, a free African who composed and taught music.

Last edited:

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Henry Ossawa Tanner was an American painter who frequently depicted biblical scenes and is best known for the paintings "Nicodemus Visiting Jesus," "The Banjo Lesson" and "The Thankful Poor." He was the first African-American painter to gain international fame.

Synopsis

Henry Ossawa Tanner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on June 21, 1859. As a young man, he studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1891, Tanner moved to Paris, and after several exhibits, gained international acclaim—becoming the first African-American painter to receive such attention. "Nicodemus Visiting Jesus" is one of his most famous works. He's also known for the paintings "The Banjo Lesson" and "The Thankful Poor." Tanner died in 1937 in Paris, France.

Early Life

A pioneering African-America artist, Henry Ossawa Tanner was born on June 21, 1859, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The oldest of nine children, Tanner was the son of an Episcopal minister and a schoolteacher.

When he was just a few years old, Tanner moved with his family to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he would spend most of his childhood. Tanner was the beneficiary of two education-minded parents; his father, Benjamin Tanner, had earned a college degree and become a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopalian Church. In Philadelphia, Tanner attended the Robert Vaux School, an all-black institution and of only a few African-American schools to offer a liberal arts curriculum.

Despite his father's initial objections, Tanner fell in love with the arts. He was 13 when he decided he wanted to become a painter, and throughout his teens, he painted and drew as much as he could. His attention to the creative side was furthered by his poor health: After falling significantly ill as a result of a taxing apprenticeship at a flourmill, the weak Tanner recuperated by staying home and painting.

Finally, in 1880, a healthy Tanner resumed a regular life and enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. There, he studied under Thomas Eakins, an influential teacher who had a profound impact on Tanner's life and work.

Tanner ended up leaving the school early, however, and moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he would teach art and run his own gallery for the next two years.

In 1891, Tanner's life took a dramatic turn with a visit to Europe. In Paris, France, in particular, Tanner discovered a culture that seemed to be light years ahead of America in race relations. Free from the prejudicial confines that defined his life in his native country, Tanner made Paris his home, living out the rest of his life there.

Artistic Success

Tanner's greatest early work depicted tender African-American scenes. Undoubtedly his most famous painting, "The Banjo Lesson," which features an older gentleman teaching a young boy how to play the banjo, was created while visiting his family in Philadelphia in 1893. The following year, he produced another masterpiece: "The Thankful Poor."

By the mid-1890s, Tanner was a success, critically admired both in the United States and Europe. In 1899, he created one of his most famous works, "Nicodemus Visiting Jesus," an oil painting on canvas depicting the biblical figure Nicodemus's meeting with Jesus Christ. For the work, he won the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts' Lippincott Prize in 1900.

Also in 1899, Tanner married a white American singer, Jessie Olssen. The couple's only child, Jesse, was born in 1903.

Throughout much of the rest of his life, even as he shifted his focus to religious scenes, Tanner continued to receive praise and honors for his work, including being named honorary chevalier of the Order of the Legion Honor—France's most distinguished award—in 1923. Four years later, Tanner was made a full academician of the National Academy of Design—becoming the first African-American to ever receive the distinction.

Death and Legacy

Henry Ossawa Tanner died at his Paris home on May 25, 1937.

In the ensuing years, his name recognition dipped. However, in the late 1960s, beginning with a solo exhibition of his work at the Smithsonian, Tanner's stature began to rise. In 1991, the Philadelphia Museum of Art assembled a touring retrospe

IllmaticDelta

Veteran