My God This is legacy.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Official African American Thread#2

- Thread starter Rhapscallion Démone

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Knew it had to.be Chi.Provident Hospital – the first Black owned and operated medical institution in the United States

Prior to 1891 there was not in this country a single hospital or training school for nurses owned and managed by colored people … there are now twelve! … and not a single failure in the effort!

– Daniel Hale Williams, 19001

Emma Reynolds, a young Chicago woman in the late 1880s, had been denied admission by each of the city’s nursing schools on account of her race. Her brother, pastor of St. Stephen’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, approached Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, a young black surgeon, for help. Dr. Williams himself, despite his degree from Chicago Medical College (now Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine), had been unable to obtain clinical privileges at any Chicago hospital, and was forced to operate in patients’ homes. He also obtained work as surgeon to the City Railway Company and by securing an appointment as a teacher of anatomy at his alma mater.2

With the support of a few prominent white citizens (Philip Armour, George Pullman, and Marshall Field among them) as well as many black individuals and organizations, Williams worked for two years to develop plans for a hospital accessible to black patients and medical practitioners, and incorporating a nursing school. In 1890 the Reverend Jenkins Jones secured a commitment from the Armour Meat Packing Company for the down payment on a three-story brick house at 29th and Dearborn Streets. In 1891 a board of trustees, an executive committee, and a finance committee were named, a community advisory board and a women’s auxiliary board were assembled, and Provident Hospital and Training School Association opened as a twelve-bed facility. Dr. Williams was appointed hospital chief of staff. It was the first black-owned and operated medical institution in the country and the first interracial hospital in Chicago — the staff and patients were both black and white.3, 4

The initial priority had been to secure an adequate hospital building. But the founders also considered community needs and the hospital’s overall mission. When the legal papers were drawn up in 1891, the charter of the “Provident Hospital and Training School Association” stated that “The object for which it is formed is to maintain a hospital and training school for nurses in the City of Chicago, Illinois, for the gratuitous treatment of the medical and surgical diseases of the sick poor.”3 In 1892 seven women, including Emma Reynolds, enrolled in the first nursing class. The first physician in surgical training, Dr. Austin Curtis (later surgeon-in-chief at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC) studied under Dr. Williams from 1891 through 1893. Dr. Williams meanwhile brought renown to himself and to Provident when he performed a thoracotomy to oversew a stab wound to the pericardium and left ventricle of a young man’s heart – thought at the time to be the first operation ever performed directly on the human heart.5

Over the next few years, demand for medical care in the community grew, and despite a national economic depression the Provident board initiated expansion plans. An 1896 funding campaign raised sufficient funds to construct a new building at 36th and Dearborn. The effort was joined by abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who gave a public lecture in Chicago and presented a donation to Dr. Williams at the new hospital site. The hospital moved to its new 65-bed location in 1898.

Although the hospital’s formation was dependent on wealthy donors, and such people stepped in at key moments in Provident’s history, the generosity of community residents was also a critical factor; and community support was not restricted to financial contributions. The strong appeal of a hospital responsive to the black community elicited repeated waves of community volunteerism.

Like any institution that endures for a century, Provident experienced many changes in its medical and administrative leadership. In 1894, President Cleveland appointed Dr. Williams Surgeon-in-Chief at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC. Williams transformed that institution by organizing the medical staff into seven departments and creating an academic affiliation with Howard University. He returned to Chicago and Provident Hospital in 1898. In the interim, however, Dr. George Cleveland Hall, an opponent of Dr. Williams, had been named medical director and his supporters had assumed control of the Provident board of trustees. The resulting tensions led Williams to secure appointment at other Chicago hospitals – his national reputation now able to overcome the prejudice that stood in the way of these same opportunities only a decade earlier – and he gradually distanced himself from Provident, finally resigning in 1912. His last decade of practice was as associate attending staff surgeon at St. Luke’s Hospital. On his retirement, St. Luke’s offered to name a patient ward in his honor but he declined, fearing it would become a segregated ward.2

Following his return from Washington Dr. Williams also began working to facilitate the establishment of other black-owned hospitals around the country. Most notably, he served as visiting professor at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, and guided the development of its hospital. The model he had started at Provident, and now brought to Meharry, was soon recapitulated at Knoxville, Kansas City, St Louis, Birmingham, Louisville, Atlanta, and Dallas.2, 4

In 1933 Provident established an educational affiliation with the University of Chicago, and as part of the agreement purchased a building on East 51st Street, near the university and previously occupied by the Chicago Lying-in Hospital. The newly refurbished, seven-story facility added considerable space for patient care, education, and administrative functions. A four-story outpatient building was constructed and two apartment buildings at 50th and Vincennes were purchased to house student nurses. As evidence of its support, the University of Chicago established a one million dollar fund for teaching and research at Provident Hospital. This became the most productive period of Provident’s history as an academic medical center, for the rise of specialization in medicine began to make postgraduate training obligatory for physicians, and Provident was one of few places in the country where African-American medical school graduates could train. In 1938 Provident became one of only nine institutions in Illinois approved by the American College of Surgeons for graduate training in surgery, and by the early 1940s the hospital also boasted programs in internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics, pathology, ophthalmology, and otolaryngology.3

During the Great Depression Provident struggled financially. But unlike other institutions who then recovered in the post-war economic expansion, Provident’s challenges only increased as black migration to Chicago swelled the population in the hospital’s Bronzeville neighborhood. The hospital narrowly averted bankruptcy in the late 1940’s, then remained reasonably stable financially over the next two decades. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 enactment of Medicare and Medicaid, however, with their non-discrimination clauses applicable to any institution receiving federal funding, had ironic consequences for institutions like Provident.4 As it became more common for black physicians to be granted privileges at larger hospitals, and for black patients, particularly those newly insured by Medicare or Medicaid, to receive care at other institutions, the financial condition of Provident worsened. Other trends, such as a shift of nursing education from hospitals to colleges of nursing, also led to a diminution of Provident’s role as an educational institution. The Provident nursing school closed in 1966.

In order to compete and continue to serve its community effectively, Provident needed to expand further and upgrade its facilities. Through the efforts of John H. Sengstacke, publisher of the Chicago Defender and longtime advocate for Provident, an alliance with Cook County Hospital, and federal grants through the Departments of Health, Education and Welfare and Housing and Urban Development, the hospital was able to open a new 300-bed pavilion adjacent to the existing 51st Street site in 1982. But the new facilities did not turn around the hospital’s fortunes, and debt only increased through the 1970s and 1980s. After declaring bankruptcy in July 1987, the hospital closed its doors that September.

The community’s devotion to the hospital remained, and various groups attempted to garner funding and political support toward its reopening. These efforts coincided with a plan by the Cook County’s Bureau of Health Services to improve service provision to residents on the south side of Chicago, and the Cook County Board of Commissioners acquired the hospital in 1991. After considerable investment in upgrading the physical plant, the Bureau reopened the facility as Provident Hospital of Cook County in August 1993.

While no longer considered a black-run hospital, Provident continues to serve the health needs of the community under the auspices of the Cook County Bureau of Health Services. Its legacy as America’s first black owned and operated hospital survives through the Provident Foundation,6 established in 1995 by Ed Gardner, a prominent businessman and the chair the hospital board at the time of its transfer to the County, and James W. Myles, a longtime union leader. The Foundation honors the legacy of Provident Hospital and Dr. Daniel Hale Williams by providing scholarship support and mentorship to aspiring doctors, nurses, and other health professionals from Chicago.

A less tangible, but more deeply embedded legacy lives on in the many people the hospital served for nearly a century. There are those whose forbearers first entered professional ranks through training as a nurse or physician at Provident, or did so themselves. There are the many Chicago natives proud to be “Provident Babies.” One, born Michelle LaVaughn Robinson in 1964, has become First Lady of the United States. Most of all there are those whose families benefitted from the care they received; it was, as noted by the venerable Chicago historian Timuel Black, “often the safest – and sometimes the only – place to go

Black Lightning

Superstar

Remembering the First Pair of African-American Sisters to Take Tennis by Storm

As Serena and Venus Williams play out the end of their careers, debates have risen about their place in tennis and American history.

Some call Serena Williams the greatest female tennis player of all time. Journalist Ian Crouch recently wrote a story for the New Yorker proclaiming Serena as America's greatest athlete. Few dispute that the sisters are one of the most dynamic sibling duos in sports history.

Yet perhaps even fewer know that the Williams sisters weren't the first African-American siblings to take tennis by storm.

That distinction belongs to Margaret and Matilda Roumania Peters, sisters from Washington D.C. who wowed crowds with their spectacular doubles play in the 1930s, '40s and '50s.

Nicknamed "Pete" and "Re-Pete," respectively, the Peters sisters played in the American Tennis Association, a league formed to give African-Americans a chance to play competitive tennis at a national level.

Established in 1916 and still alive today, the ATA is the oldest black sports organization in the U.S. Similar to the Negro Leagues in baseball, the ATA offered top black tennis players—who were denied access to all-white professional leagues—a stage to showcase their talents.

The ATA sponsored tournaments throughout the country. Although top players didn't make a living from these tournaments, they were indeed stars. The Peters sisters were often asked to pose for publicity shots and sign autographs. Crowds of blacks and whites traveled to watch them play.

Known for their slice serves, powerful backhands and quick chop shots, the Peters sisters became pseudo-celebrities. Margaret (sometimes called "Big Pete") was the oldest by two years and the taller sister. Matilda, (Re-Pete) was the younger, feistier sister.

According to Cecil Harris and Larryette Kyle-DeBose's book Charging the Net: A History of Blacks in Tennis, actor and dancer Gene Kelly, stationed at a Navy Base near Washington D.C. during World War II, dropped in to watch the sisters play in 1944. Kelly would also play tennis with the Peters sisters when he was in town.

In a Jan. 10, 1942 edition of the Afro American newspaper, the "famous Peters sisters" made headlines for winning a fourth-consecutive doubles title.

The sisters began playing tennis as young girls at a park across from their home in Georgetown. They were recruited to play at Tuskegee University. So close were they that Margaret waited for her sister to graduate high school so that they could enroll at Tuskegee together.

Segregation and discrimination forced the ATA to hold most of its tournaments at historically black colleges and universities. These tournaments became social events for affluent blacks. The annual national championships were highly anticipated and included parties, formal dances and fashion shows.

The ATA operated in a parallel existence to the United States Lawn Tennis Association, now the USTA. Before the 1950s, the USTA refused to allow blacks to compete against whites. This included a talented young player named Althea Gibson who was making noise on the ATA Tour.

Gibson, younger than the Peters sisters by nearly a decade, moved quickly up the ranks of the ATA Tour. She won the national championship in 1944 and 1945. She suffered a loss in the finals in 1946 before winning 10 straight titles from 1947 to 1956.

That loss was to Matilda "Re-Pete" Peters, the younger sister. Matilda is the only African-American woman to ever defeat Gibson.

Four years later, pressured by ATA officials and Alice Marble, Gibson was invited to compete in the U.S. National Championships, now the U.S. Open. Already in her mid-20s, Gibson made her debut at Forest Lawn in 1950. Two years later, George Stewart would become the first black man to play at the U.S. Open.

Meanwhile, the Peters sisters, like so many other talented African-American tennis players, remained on the ATA tour. They dominated the ATA, winning 14 doubles championships, a record that still remains. Matilda also won two ATA singles titles.

By the time color lines began to be broken, the sisters were in their 30s, about the age Venus and Serena Williams are now. One's mid-30s are hardly the years to begin a professional tennis career.

In 2003, the USTA, the same organization that denied African-Americans a chance to compete during most of the sisters' careers, honored the Peters duo with an achievement award during the Fed Cup quarterfinals in their hometown.

The Peters sisters were also inducted into the USTA's Mid-Atlantic Section Hall of Fame in November 2003. They were inducted into the Black Tennis Hall of Fame in 2012.

Matilda died of pneumonia in May 2003. Margaret died in November 2004.

It's hard to say how their games would have stacked up against those of Helen Wills Moody and Alice Marble. It would have been nice to see.

However, desegregation doors didn't swing wide open for African-American athletes. As was the case with Jackie Robinson in Major League Baseball and Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton in the NBA, in the 1950s only a hand-picked, select few were given opportunities.

That's why although they reached prominence in tennis decades before the Williams sisters, it seems odd to classify the Peters sisters as pioneers. After all, they played tennis at Tuskegee, a university that had been offering tennis since the 1890s.

Long after the Peters sisters retired from tennis, the ATA continued to attract top black players. Lori McNeil, Chanda Rubin and Zina Garrison all played in the ATA. Garrison, a Wimbledon finalist in 1990, won the ATA singles titles in 1979 and 1980 and the doubles titles in 1980 and 1981.

Instead, consider the Peters sisters forgotten stars. Their stories, buried beneath the weight of segregation, have existed all along. Gibson, the first African-American to win a Grand Slam, is the pioneer. The Peters sisters, like several talented African-American baseball players who made Negro League All-Star teams that left Robinson off, were simply the unlucky uninvited.

They lacked an invitation, not talent. Those who watched them compete witnessed two dynamic and athletic tennis superstars. Even as they accumulate posthumous accolades, their unearthed stories shine a light on misplaced tennis gems.

As Serena and Venus Williams play out the end of their careers, debates have risen about their place in tennis and American history.

Some call Serena Williams the greatest female tennis player of all time. Journalist Ian Crouch recently wrote a story for the New Yorker proclaiming Serena as America's greatest athlete. Few dispute that the sisters are one of the most dynamic sibling duos in sports history.

Yet perhaps even fewer know that the Williams sisters weren't the first African-American siblings to take tennis by storm.

That distinction belongs to Margaret and Matilda Roumania Peters, sisters from Washington D.C. who wowed crowds with their spectacular doubles play in the 1930s, '40s and '50s.

Nicknamed "Pete" and "Re-Pete," respectively, the Peters sisters played in the American Tennis Association, a league formed to give African-Americans a chance to play competitive tennis at a national level.

Established in 1916 and still alive today, the ATA is the oldest black sports organization in the U.S. Similar to the Negro Leagues in baseball, the ATA offered top black tennis players—who were denied access to all-white professional leagues—a stage to showcase their talents.

The ATA sponsored tournaments throughout the country. Although top players didn't make a living from these tournaments, they were indeed stars. The Peters sisters were often asked to pose for publicity shots and sign autographs. Crowds of blacks and whites traveled to watch them play.

Known for their slice serves, powerful backhands and quick chop shots, the Peters sisters became pseudo-celebrities. Margaret (sometimes called "Big Pete") was the oldest by two years and the taller sister. Matilda, (Re-Pete) was the younger, feistier sister.

According to Cecil Harris and Larryette Kyle-DeBose's book Charging the Net: A History of Blacks in Tennis, actor and dancer Gene Kelly, stationed at a Navy Base near Washington D.C. during World War II, dropped in to watch the sisters play in 1944. Kelly would also play tennis with the Peters sisters when he was in town.

In a Jan. 10, 1942 edition of the Afro American newspaper, the "famous Peters sisters" made headlines for winning a fourth-consecutive doubles title.

The sisters began playing tennis as young girls at a park across from their home in Georgetown. They were recruited to play at Tuskegee University. So close were they that Margaret waited for her sister to graduate high school so that they could enroll at Tuskegee together.

Segregation and discrimination forced the ATA to hold most of its tournaments at historically black colleges and universities. These tournaments became social events for affluent blacks. The annual national championships were highly anticipated and included parties, formal dances and fashion shows.

The ATA operated in a parallel existence to the United States Lawn Tennis Association, now the USTA. Before the 1950s, the USTA refused to allow blacks to compete against whites. This included a talented young player named Althea Gibson who was making noise on the ATA Tour.

Gibson, younger than the Peters sisters by nearly a decade, moved quickly up the ranks of the ATA Tour. She won the national championship in 1944 and 1945. She suffered a loss in the finals in 1946 before winning 10 straight titles from 1947 to 1956.

That loss was to Matilda "Re-Pete" Peters, the younger sister. Matilda is the only African-American woman to ever defeat Gibson.

Four years later, pressured by ATA officials and Alice Marble, Gibson was invited to compete in the U.S. National Championships, now the U.S. Open. Already in her mid-20s, Gibson made her debut at Forest Lawn in 1950. Two years later, George Stewart would become the first black man to play at the U.S. Open.

Meanwhile, the Peters sisters, like so many other talented African-American tennis players, remained on the ATA tour. They dominated the ATA, winning 14 doubles championships, a record that still remains. Matilda also won two ATA singles titles.

By the time color lines began to be broken, the sisters were in their 30s, about the age Venus and Serena Williams are now. One's mid-30s are hardly the years to begin a professional tennis career.

In 2003, the USTA, the same organization that denied African-Americans a chance to compete during most of the sisters' careers, honored the Peters duo with an achievement award during the Fed Cup quarterfinals in their hometown.

The Peters sisters were also inducted into the USTA's Mid-Atlantic Section Hall of Fame in November 2003. They were inducted into the Black Tennis Hall of Fame in 2012.

Matilda died of pneumonia in May 2003. Margaret died in November 2004.

It's hard to say how their games would have stacked up against those of Helen Wills Moody and Alice Marble. It would have been nice to see.

However, desegregation doors didn't swing wide open for African-American athletes. As was the case with Jackie Robinson in Major League Baseball and Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton in the NBA, in the 1950s only a hand-picked, select few were given opportunities.

That's why although they reached prominence in tennis decades before the Williams sisters, it seems odd to classify the Peters sisters as pioneers. After all, they played tennis at Tuskegee, a university that had been offering tennis since the 1890s.

Long after the Peters sisters retired from tennis, the ATA continued to attract top black players. Lori McNeil, Chanda Rubin and Zina Garrison all played in the ATA. Garrison, a Wimbledon finalist in 1990, won the ATA singles titles in 1979 and 1980 and the doubles titles in 1980 and 1981.

Instead, consider the Peters sisters forgotten stars. Their stories, buried beneath the weight of segregation, have existed all along. Gibson, the first African-American to win a Grand Slam, is the pioneer. The Peters sisters, like several talented African-American baseball players who made Negro League All-Star teams that left Robinson off, were simply the unlucky uninvited.

They lacked an invitation, not talent. Those who watched them compete witnessed two dynamic and athletic tennis superstars. Even as they accumulate posthumous accolades, their unearthed stories shine a light on misplaced tennis gems.

Black Lightning

Superstar

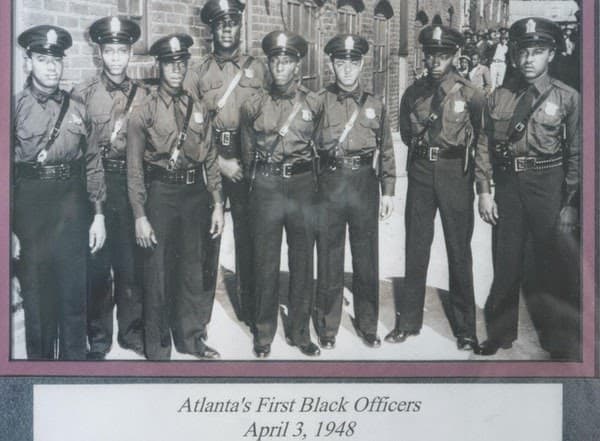

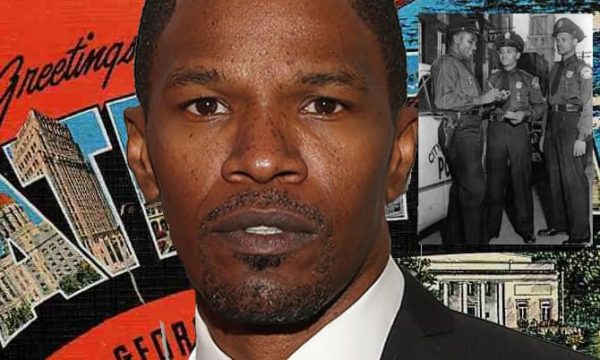

9 Startling Facts About the First Black Police Officers in Atlanta

Token Origins

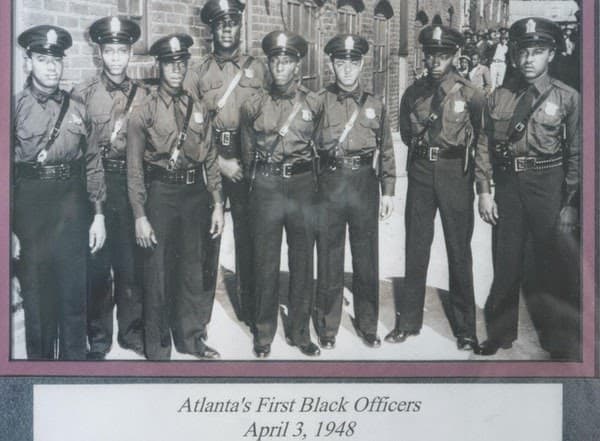

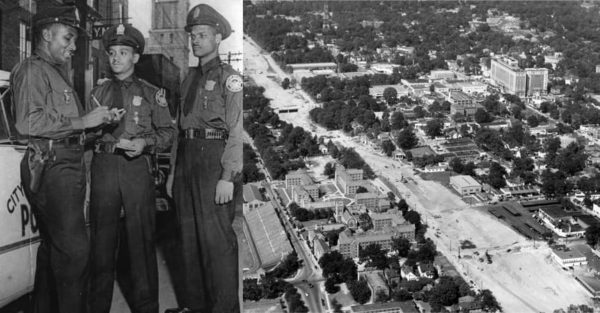

Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield pushed for the integration of the city’s police force for political reasons, not ethical ones. By the 1940s, the African-American vote in the city became a major factor in winning or losing an election. And Black leaders in prominent communities like Auburn Avenue knew this. They demanded that Black officers be part of the police force. Hartsfield hired eight Black police officers in 1948 and in return he got the Black vote.

With Great Power Comes No Respect or Authority

In 1948, the first Black officers were: Claude Dixon, Henry Hooks, Johnnie Jones, Ernest Lyons, Robert McKibbens, John Sanders, Willard Strickland and Willie Elkins. These men were proud to be on the force but they had no power, respect or real authority in their new roles. This new opportunity brought discrimination from within the department and from the community itself.

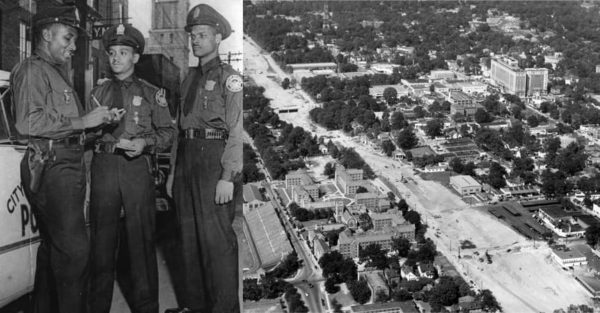

They could not arrest whites, ride in patrol cars, or use police headquarters. They first began duty on April 3, 1948 by patrolling Auburn Avenue. The eight carried out their police operations at a nearby Y.M.C.A.

A Little Progress But Not Much

In the first seven years of the experiment, Black officers had to wait their turn to have actual power. According to Atlantapd.org, 1955 saw a steep decline in crime. In fact, major crimes — including murder — fell to 7 percent. This year was monumental for Black officers because Howard Baugh and Ernest Lyons become the first African-American police detectives in the APD. However, in this 7-year span there were only 15 Black officers on the force.

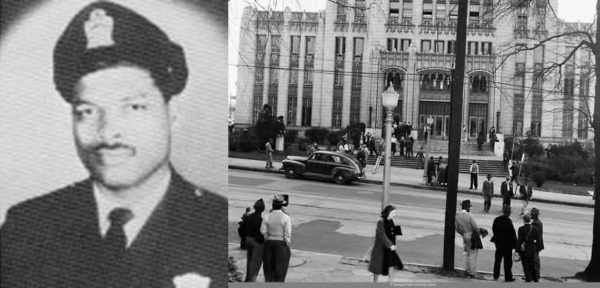

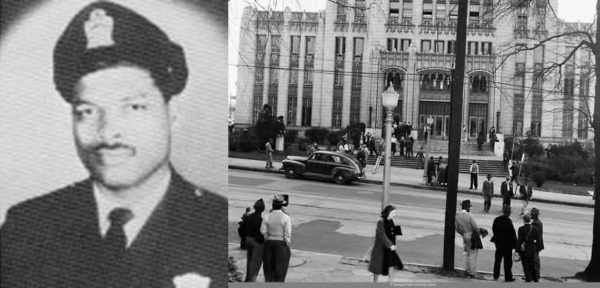

Howard Baugh

It would take six more years until a Black officer had a leadership role. In 1961, detective Howard Baugh became the first African-American superior officer on March 31. Baugh lived next to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and was also a civil rights activist while on the force.

Claude Everett Mundy, Jr.

In 1961, the first Black officer was killed in the line of duty. According to Odmp.org, Mundy went into a two-story building trying to track down a burglary suspect. He knocked on the door of an apartment and asked the resident to open the door. The door opened and a barrage of gunfire came at him. His partner came back for him, but Mundy died from his wounds on Jan. 5 before EMTs could arrive.

A Step Closer to Equality

In 1962, Black officers were now allowed to arrest all whites, no matter their social status. If they were engaged in criminal activities, they could be apprehended. At this time, the use of one-person patrol cars was expanded.

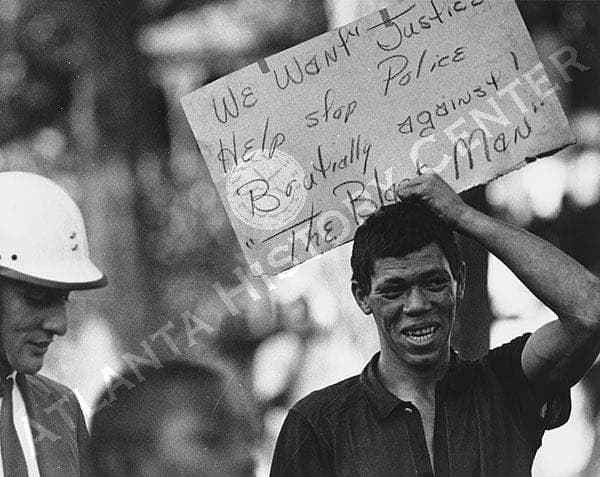

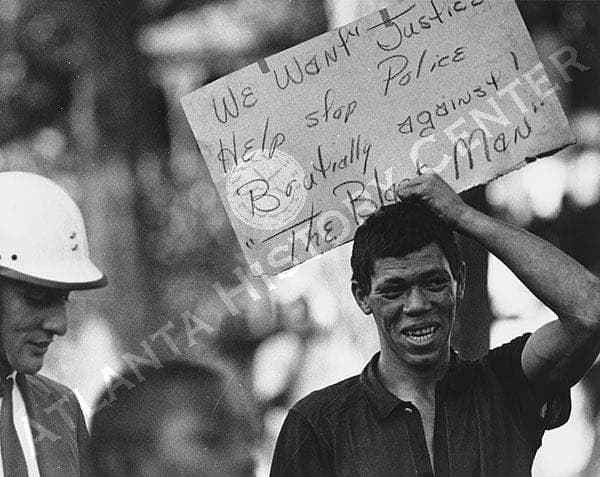

The Summerhill Riot

By 1966, Black officers were assigned to regular patrol, and a crime prevention bureau was established. This progress occurred as the Civil Rights Movement and riots were taking place around the country. In fact, Atlanta had its own riot and accusations of police brutality to deal with. On September 6, the Summerhill Riot took place in the historic Black and Jewish neighborhood. The four-day riot ended with one person dead and 20 injured. Many of the protesters were young and inspired by Stokely Carmichael and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

The Black Female Officers

In 1971, the Atlanta police also began to push for gender equality. So the first African-American woman, Linnie Hollowman, was hired to patrol the Atlanta streets. Like the first eight black officers, she faced an uphill battle to be considered an equal. The first two women to gain rank were Thetus Knox and Blanche Nichols two decades later. Knox served as field patrol sergeant, section commander of the criminal investigations division and zone commander in her career. These two women paved the way for Beverly J. Harvard to become the first African-American woman to hold the rank of chief of police in any major U.S. city in 1994.

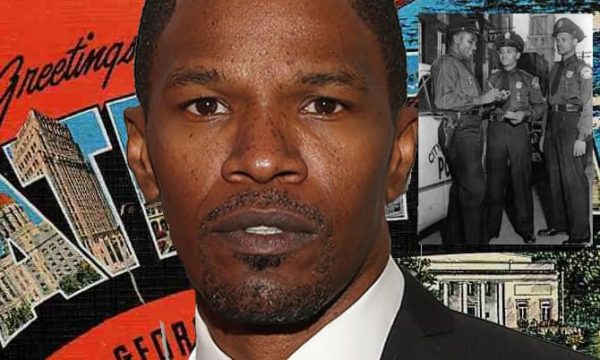

From Relative Obscurity to Television

Back in January, Shadow and Act reported that Amy Pascal and Sony Pictures Television will team up with Jamie Foxx to executive produce a Black cop TV series. There isn’t a network, cast or release date as of yet. However, the show is based on Thomas Mullen’s Darktown. The recent novel documents the racial controversy surrounding the first eight Black officers in 1948.

The fictitious crime novel tells the story of two officers searching for a Black woman who was last seen in a car driven by a white man. Officers Boggs and Smith will risk everything to find the woman. If the show is tied to the book, it will have a similar feel to 2014’s True Detective season 1.

Token Origins

Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield pushed for the integration of the city’s police force for political reasons, not ethical ones. By the 1940s, the African-American vote in the city became a major factor in winning or losing an election. And Black leaders in prominent communities like Auburn Avenue knew this. They demanded that Black officers be part of the police force. Hartsfield hired eight Black police officers in 1948 and in return he got the Black vote.

With Great Power Comes No Respect or Authority

In 1948, the first Black officers were: Claude Dixon, Henry Hooks, Johnnie Jones, Ernest Lyons, Robert McKibbens, John Sanders, Willard Strickland and Willie Elkins. These men were proud to be on the force but they had no power, respect or real authority in their new roles. This new opportunity brought discrimination from within the department and from the community itself.

They could not arrest whites, ride in patrol cars, or use police headquarters. They first began duty on April 3, 1948 by patrolling Auburn Avenue. The eight carried out their police operations at a nearby Y.M.C.A.

A Little Progress But Not Much

In the first seven years of the experiment, Black officers had to wait their turn to have actual power. According to Atlantapd.org, 1955 saw a steep decline in crime. In fact, major crimes — including murder — fell to 7 percent. This year was monumental for Black officers because Howard Baugh and Ernest Lyons become the first African-American police detectives in the APD. However, in this 7-year span there were only 15 Black officers on the force.

Howard Baugh

It would take six more years until a Black officer had a leadership role. In 1961, detective Howard Baugh became the first African-American superior officer on March 31. Baugh lived next to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and was also a civil rights activist while on the force.

Claude Everett Mundy, Jr.

In 1961, the first Black officer was killed in the line of duty. According to Odmp.org, Mundy went into a two-story building trying to track down a burglary suspect. He knocked on the door of an apartment and asked the resident to open the door. The door opened and a barrage of gunfire came at him. His partner came back for him, but Mundy died from his wounds on Jan. 5 before EMTs could arrive.

A Step Closer to Equality

In 1962, Black officers were now allowed to arrest all whites, no matter their social status. If they were engaged in criminal activities, they could be apprehended. At this time, the use of one-person patrol cars was expanded.

The Summerhill Riot

By 1966, Black officers were assigned to regular patrol, and a crime prevention bureau was established. This progress occurred as the Civil Rights Movement and riots were taking place around the country. In fact, Atlanta had its own riot and accusations of police brutality to deal with. On September 6, the Summerhill Riot took place in the historic Black and Jewish neighborhood. The four-day riot ended with one person dead and 20 injured. Many of the protesters were young and inspired by Stokely Carmichael and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

The Black Female Officers

In 1971, the Atlanta police also began to push for gender equality. So the first African-American woman, Linnie Hollowman, was hired to patrol the Atlanta streets. Like the first eight black officers, she faced an uphill battle to be considered an equal. The first two women to gain rank were Thetus Knox and Blanche Nichols two decades later. Knox served as field patrol sergeant, section commander of the criminal investigations division and zone commander in her career. These two women paved the way for Beverly J. Harvard to become the first African-American woman to hold the rank of chief of police in any major U.S. city in 1994.

From Relative Obscurity to Television

Back in January, Shadow and Act reported that Amy Pascal and Sony Pictures Television will team up with Jamie Foxx to executive produce a Black cop TV series. There isn’t a network, cast or release date as of yet. However, the show is based on Thomas Mullen’s Darktown. The recent novel documents the racial controversy surrounding the first eight Black officers in 1948.

The fictitious crime novel tells the story of two officers searching for a Black woman who was last seen in a car driven by a white man. Officers Boggs and Smith will risk everything to find the woman. If the show is tied to the book, it will have a similar feel to 2014’s True Detective season 1.

Black Lightning

Superstar

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Thurgood Thurston III

#LLNB #LLLB #E4R x 2 🖤🖤🖤🆚🌀🌀

Learning so much things that I never knew.

Black Lightning

Superstar

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

On this day in Black history, we honor Dr. Ebony Jade Hilton. Dr. Hilton was born in the rural town of Little Africa, South Carolina and at the age of 8 years old, decided she wanted to be a doctor. From that day forward her mother called her, Dr. Hilton. She attributes her entire career and the success that followed to that small gesture. She graduated from Spartanburg High School in 2000 and in 2004, graduated Magna Cum Laude from The College of Charleston as a triple major with degrees in Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Inorganic Chemistry. She then began her medical studies at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and following graduation in 2008, continued at MUSC to complete of her Anesthesiology residency and Critical Care fellowship. On July 1, 2013, Dr. Hilton became the first African-American female anesthesiologist to be hired at MUSC since its opening in 1824. Throughout her studies health disparities and bridging the gap between physicians and patients has been her primary focus. Dr. Hilton is also an activist for social change and a mentor in her community.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Thomas V. Gibbs (1855–1898)

served in the Florida House of Representatives for Duval County in 1885 and 1887. In 1885 he participated in the Florida Constitutional Convention. Gibbs was a cofounder of the State Normal College for Colored Students. Today, the school, now Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), is one of the nation's most prominent historically black schools.

History of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU)

Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University was founded as the State Normal College for Colored Students, and on October 3, 1887, it began classes with fifteen students and two instructors. Today, FAMU, as it has become affectionately known, is the premiere school among historically black colleges and universities. Prominently located on the highest hill in Florida’s capital city of Tallahassee, Florida A&M University remains the only historically black university in the eleven member State University System of Florida.

In 1884, Thomas Van Renssaler Gibbs, a Duval County educator, was elected to the Florida legislature. Although his political career ended abruptly because of the resurgence of segregation, Representative Gibbs was successful in orchestrating the passage of House Bill 133, in 1884, which established a white normal school in Gainesville, FL, and a colored school in Jacksonville. The bill passed, creating both institutions; however, the stated decided to relocate the colored school to Tallahassee.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Kevin Stonewall

Keven Stonewall has made the science community proud with his groundbreaking research

At 19, Stonewall conducted research on a colon cancer vaccine thru a treatment called immunotherapy, revealing the vaccine's effectiveness hinged on the age group it was given to. An age specific vaccine, Stonewall found this out running an experiment on a set of older and young mice, injecting a mitoxantrone type vaccine into each. He then shot both groups with aggressive colon cancer cells, and monitored them. After a few days, Stonewall found that the aggressive cells inside the young mice were completely gone while the older mice were still affected.

“He should be heralded for helping to develop more effective colon cancer treatments,” Carl Ruby, Rush University Professor who ran the lab where Stonewall conducted research. "Stonewall's path to becoming a cancer researcher began in 5th grade."

Meet Keven Stonewall The 22 Year Old Ending Colon Cancer