You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Africa the Media Doesn't Tell You About

- Thread starter TommyHilltrigga

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?The year so far: Here are the 10 Africans who've done impressive things, that you must have dinner with

29 SEP 2015 15:50M&G AFRICA REPORTER

(Photo/Asmelash Zerefu Facebook)

A STORY recently came out about how an Ethiopian man, obsessed with aviation, decided to build himself a plane. Even though the Ethiopian Airlines Aviation Academy rejected Asmelash Zerefu’s bid to enrol (he was too short) he decided to set about on his own and fulfil his dreams, single-handedly constructed Ethiopia’s first ever home-built aircraft from scratch by reading aviation books and watching YouTube tutorials.

The result is a completed “K-570A”, a two-seat, open-tandem parasol light aircraft - he’s yet to fly it successfully though.

All over the continent individuals are dreaming big - and those determined enough have reached some inspiring heights. Here are some more of those African individuals who have, over the past year, strived to achieve some remarkable goals - and who would make fascinating dinner guests:

Macky Sall, President of Senegal

Over the past year this West African president has put many of his African counterparts to shame with his sheer enthusiasm, vision and commitment to projects - all attributes that would make him a particularly engaging dinner companion.

He singled out higher education as an area for investment, putting himself out as a champion for the cause and pushing for more heads of state to follow suit. Earlier this year he began actively lobbying African countries to allocate more than 1% of gross domestic product to research, hosted the African Higher Education Summit in Dakar and announced the construction of two new universities in Senegal, each with a capacity for 30,000 students. Sall was also critical in the push to build Senegal’s reputation as a digital nation with the launch of an ambitious project to create Africa’s version of silicon valley, “Diamniadio Technology Park”, located about 40km from the capital Dakar it will feature data and higher education centres.

At a time when several African leaders are tearing up constitutions to remove presidential term limits, and even, as in Burundi, taking their countries back to war so they can cling to power, in May Sall proposed to reduce his country’spresidential term from seven to five years!

(Photo/EU/European Parliament).

READ: Senegal’s Macky Sall makes African leaders look bad, but with Mandela for a pacesetter, he’s in good company

Samrawit Weldemariam, RIDE founder

Samrawit Weldemariam has taken on Uber in Ethiopia with the launch of RIDE this year, an on-demand SMS taxi service. The service registers blue and white city taxi drivers and connects them automatically to customers who SMS their location. Aimed at making travelling in Addis easier, to date she has registered and activated more than 450 Taxi drivers all over Addis with around 2500 drivers on their waiting list to curb future shortages.

Daniel Teklehaimanot, International cycling champion

Boredom wouldn’t be on the menu if you sat down with the first black African to start the Tour de France! In 2015 at the Critérium du Dauphiné, this Eritrean cyclist, who started cycling at the age of 10, won the first World Tour jersey in MTN-Qhubeka’s history by taking the mountains competition. This year he also became the first black African rider to wear the polka dot jersey after winning it on Stage 6 of the 2015 Tour de France. For the record, she shared the honours with fellow countryman Merhawi Kudus, although he had a quieter race.

(Photo/Doug Pensinger/Getty Images).

Elvis Ogweno, Tactical Combat Paramedic

With the Ebola crisis in West Africa, which claimed over 11,000 lives, this has been an incredibly tough year for health personnel on the front lines. One hero has had a particularly colourful career, having attended to the 1998 bombings in Kenya and protracted conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, South Sudan and Congo. Now Elvis is working to save lives in the 2014-2015 Ebola epidemic. Working with the International Medical Corps, he leads an ambulance team designated for transporting both suspected and confirmed Ebola patients and blood specimen in Liberia. No matter where, no matter what the conditions.

Ugaaso Abakar, Instagram Diva

Sure to be a colourful dinner guest, what started off as a way of making her friends laugh turned this Somali instagrammer into a global sensation. With over 40,000 followers Abakar started working to counter negative stereotypes of Somalia, and Mogadishu in particular. The self-styled comedienne posts videos and photos of daily life, presenting a visual commentary which most would never have imagined came out of Somalia. When war broke out in Somalia in 1991, Abakar had fled to Canada with her grandparents and only returned to Somalia in 2014. When asked by the BBC if her Instagram feed only represented the lives of Mogadishu’s privileged society, she responded in the negative. “I don’t feel privileged at all. A lot of us who came to Somalia are here because we want to be here.”

Rida Essa, Commander of the Coastguard in Misrata, Libya

This year the number of migrants and refugees trying to make their way to Europe has reached epic proportions. More than 2,600 people have died trying to cross the Mediterranean in 2015, many of them from Africa, all in search of a better life. One of the groups trying to prevent migrants from crossing the sea, save them from drowning and bring them back to safety, are the coastguards from Libya’s strategic Mediterranean port city of Misrata. But this coastguard, led by Colonel Rida Edda, faces immense challenges of its own - it has only eight boats to patrol 1,930km of coastline, operates in a country which is barely functioning and is also trying to deal with illegal fishing, terrorists and gunrunners. The coastguard’s commander has had his work cut out for him and would have some truly incredible feats to describe over dinner.

Adnane Remmal, Researcher

One of the greatest African scientific creations of the year came from Moroccan Adnane Remmal. He came up with a revolutionary antibiotic alternative for livestock farmers which reduces health hazards in livestock and prevents the transmission of multi-resistant bacteria and carcinogens to humans through consumption of milk, eggs and meat. His patented solution saw the Moroccan researcher win the 2015 Innovation Prize for Africa.

Denis Mukwege, Gynecologist

Denis Mukwege is a Congolese gynecologist who is credited with saving the lives of at least 40,000 women, raped during conflict. He founded and works in Panzi Hospital in Bukavu, where he specialises in the treatment of women who have been gang-raped, becoming the the world’s leading expert on how to repair the internal physical damage caused by it.

This year has been exciting for the doctor, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws by Harvard University and a movie on his work, “The Man Who Mends Women” was released. Unfortunately the film has been banned from being shown in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Margaret Kenyatta, First Lady of Kenya

Kenya’s First Lady has not taken her position, role or ability to influence lightly this year. An elegant, unassuming First Lady who doesn’t say much, she has been running a campaign to reduce child maternal mortality rates, dubbed the “Beyond Zero Campaign”. On October 24th 2014, she was named UN Person of the Year for her efforts. As part of the campaign, this year she organised a huge half marathon, which she participated in along with 15,000 participants - aimed at raising funds for the Beyond Zero campaign. Even before the event began, the campaign had already managed to buy and deliver 21 fully equipped mobile clinics to 21 counties as part of the campaigns objective to improve maternal and child health.

(Photo/Facebook/BeyondZero).

Aliko Dangote, Entrepreneur

He doesn’t slow down. Nigerian billionaire, Aliko Dangote, has continued to cause waves. This year Forbes have him down as the 67th richest person in the world and name him as the richest man in Africa with a net worth of about $17.7 billion.

Earlier this year he announced that he’s expanding his cement empire to Asia, signed a deal with a Chinese state-owned engineering company (worth $4.3bn) to build seven new factories in Africa and expressed an interest in purchasing the English football team Arsenal. Through all of this ups and downs, he would make for extremely interesting conversation - and you wouldn’t have to listen to him or laugh at his jokes only because he is filthy rich.

The year so far: Here are the 10 Africans who've done impressive things, that you must have dinner with

29 SEP 2015 15:50M&G AFRICA REPORTER

(Photo/Asmelash Zerefu Facebook)

A STORY recently came out about how an Ethiopian man, obsessed with aviation, decided to build himself a plane. Even though the Ethiopian Airlines Aviation Academy rejected Asmelash Zerefu’s bid to enrol (he was too short) he decided to set about on his own and fulfil his dreams, single-handedly constructed Ethiopia’s first ever home-built aircraft from scratch by reading aviation books and watching YouTube tutorials.

The result is a completed “K-570A”, a two-seat, open-tandem parasol light aircraft - he’s yet to fly it successfully though.

All over the continent individuals are dreaming big - and those determined enough have reached some inspiring heights. Here are some more of those African individuals who have, over the past year, strived to achieve some remarkable goals - and who would make fascinating dinner guests:

Macky Sall, President of Senegal

Over the past year this West African president has put many of his African counterparts to shame with his sheer enthusiasm, vision and commitment to projects - all attributes that would make him a particularly engaging dinner companion.

He singled out higher education as an area for investment, putting himself out as a champion for the cause and pushing for more heads of state to follow suit. Earlier this year he began actively lobbying African countries to allocate more than 1% of gross domestic product to research, hosted the African Higher Education Summit in Dakar and announced the construction of two new universities in Senegal, each with a capacity for 30,000 students. Sall was also critical in the push to build Senegal’s reputation as a digital nation with the launch of an ambitious project to create Africa’s version of silicon valley, “Diamniadio Technology Park”, located about 40km from the capital Dakar it will feature data and higher education centres.

At a time when several African leaders are tearing up constitutions to remove presidential term limits, and even, as in Burundi, taking their countries back to war so they can cling to power, in May Sall proposed to reduce his country’spresidential term from seven to five years!

(Photo/EU/European Parliament).

READ: Senegal’s Macky Sall makes African leaders look bad, but with Mandela for a pacesetter, he’s in good company

Samrawit Weldemariam, RIDE founder

Samrawit Weldemariam has taken on Uber in Ethiopia with the launch of RIDE this year, an on-demand SMS taxi service. The service registers blue and white city taxi drivers and connects them automatically to customers who SMS their location. Aimed at making travelling in Addis easier, to date she has registered and activated more than 450 Taxi drivers all over Addis with around 2500 drivers on their waiting list to curb future shortages.

Daniel Teklehaimanot, International cycling champion

Boredom wouldn’t be on the menu if you sat down with the first black African to start the Tour de France! In 2015 at the Critérium du Dauphiné, this Eritrean cyclist, who started cycling at the age of 10, won the first World Tour jersey in MTN-Qhubeka’s history by taking the mountains competition. This year he also became the first black African rider to wear the polka dot jersey after winning it on Stage 6 of the 2015 Tour de France. For the record, she shared the honours with fellow countryman Merhawi Kudus, although he had a quieter race.

(Photo/Doug Pensinger/Getty Images).

Elvis Ogweno, Tactical Combat Paramedic

With the Ebola crisis in West Africa, which claimed over 11,000 lives, this has been an incredibly tough year for health personnel on the front lines. One hero has had a particularly colourful career, having attended to the 1998 bombings in Kenya and protracted conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, South Sudan and Congo. Now Elvis is working to save lives in the 2014-2015 Ebola epidemic. Working with the International Medical Corps, he leads an ambulance team designated for transporting both suspected and confirmed Ebola patients and blood specimen in Liberia. No matter where, no matter what the conditions.

Ugaaso Abakar, Instagram Diva

Sure to be a colourful dinner guest, what started off as a way of making her friends laugh turned this Somali instagrammer into a global sensation. With over 40,000 followers Abakar started working to counter negative stereotypes of Somalia, and Mogadishu in particular. The self-styled comedienne posts videos and photos of daily life, presenting a visual commentary which most would never have imagined came out of Somalia. When war broke out in Somalia in 1991, Abakar had fled to Canada with her grandparents and only returned to Somalia in 2014. When asked by the BBC if her Instagram feed only represented the lives of Mogadishu’s privileged society, she responded in the negative. “I don’t feel privileged at all. A lot of us who came to Somalia are here because we want to be here.”

Rida Essa, Commander of the Coastguard in Misrata, Libya

This year the number of migrants and refugees trying to make their way to Europe has reached epic proportions. More than 2,600 people have died trying to cross the Mediterranean in 2015, many of them from Africa, all in search of a better life. One of the groups trying to prevent migrants from crossing the sea, save them from drowning and bring them back to safety, are the coastguards from Libya’s strategic Mediterranean port city of Misrata. But this coastguard, led by Colonel Rida Edda, faces immense challenges of its own - it has only eight boats to patrol 1,930km of coastline, operates in a country which is barely functioning and is also trying to deal with illegal fishing, terrorists and gunrunners. The coastguard’s commander has had his work cut out for him and would have some truly incredible feats to describe over dinner.

Adnane Remmal, Researcher

One of the greatest African scientific creations of the year came from Moroccan Adnane Remmal. He came up with a revolutionary antibiotic alternative for livestock farmers which reduces health hazards in livestock and prevents the transmission of multi-resistant bacteria and carcinogens to humans through consumption of milk, eggs and meat. His patented solution saw the Moroccan researcher win the 2015 Innovation Prize for Africa.

Denis Mukwege, Gynecologist

Denis Mukwege is a Congolese gynecologist who is credited with saving the lives of at least 40,000 women, raped during conflict. He founded and works in Panzi Hospital in Bukavu, where he specialises in the treatment of women who have been gang-raped, becoming the the world’s leading expert on how to repair the internal physical damage caused by it.

This year has been exciting for the doctor, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws by Harvard University and a movie on his work, “The Man Who Mends Women” was released. Unfortunately the film has been banned from being shown in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Margaret Kenyatta, First Lady of Kenya

Kenya’s First Lady has not taken her position, role or ability to influence lightly this year. An elegant, unassuming First Lady who doesn’t say much, she has been running a campaign to reduce child maternal mortality rates, dubbed the “Beyond Zero Campaign”. On October 24th 2014, she was named UN Person of the Year for her efforts. As part of the campaign, this year she organised a huge half marathon, which she participated in along with 15,000 participants - aimed at raising funds for the Beyond Zero campaign. Even before the event began, the campaign had already managed to buy and deliver 21 fully equipped mobile clinics to 21 counties as part of the campaigns objective to improve maternal and child health.

(Photo/Facebook/BeyondZero).

Aliko Dangote, Entrepreneur

He doesn’t slow down. Nigerian billionaire, Aliko Dangote, has continued to cause waves. This year Forbes have him down as the 67th richest person in the world and name him as the richest man in Africa with a net worth of about $17.7 billion.

Earlier this year he announced that he’s expanding his cement empire to Asia, signed a deal with a Chinese state-owned engineering company (worth $4.3bn) to build seven new factories in Africa and expressed an interest in purchasing the English football team Arsenal. Through all of this ups and downs, he would make for extremely interesting conversation - and you wouldn’t have to listen to him or laugh at his jokes only because he is filthy rich.

The year so far: Here are the 10 Africans who've done impressive things, that you must have dinner with

Africa’s looming debt crises

29 September2015

The 1980s are calling. According to Bloomberg:

Zambia’s kwacha fell the most on record after Moody’s Investors Service cut the credit rating of Africa’s second-biggest copper producer, a move the government rejected and told investors to ignore…..

Zambia’s economy faces “a perfect storm” of plunging prices for the copper it relies on for 70 percent of export earnings at the same time as its worst power shortage, Ronak Gopaldas, a credit risk analyst at Rand Merchant Bank in Johannesburg, said by phone. Growth will slow to 3.4 percent in 2015, missing the government’s revised target of 5 percent, Barclays Plc said in a note last week. That would be the most sluggish pace since 2001.

The looming debt crisis will hit Zambia and other commodity exporters hard. As I noted two years ago, the vast majority of the African countries that have floated dollar-denominated bonds are heavily dependent on commodity exports. Many of them are already experiencing fiscal blues on account of the global commodity slump (see for example Angola, Zambia and Ghana). This will probably get worse. And the double whammy of plummeting currencies and reduced commodity exports will increase the real cost of external debt (on top of fueling domestic inflation). I do not envy African central bankers.

Making sure that the looming debt crises do not result in a disastrous retrenchment of the state in Africa, like happened in the 1980s and 1990s, is perhaps the biggest development challenge of our time. Too bad all the attention within the development community is focused elsewhere.

Africa's looming debt crises

29 September2015

The 1980s are calling. According to Bloomberg:

Zambia’s kwacha fell the most on record after Moody’s Investors Service cut the credit rating of Africa’s second-biggest copper producer, a move the government rejected and told investors to ignore…..

Zambia’s economy faces “a perfect storm” of plunging prices for the copper it relies on for 70 percent of export earnings at the same time as its worst power shortage, Ronak Gopaldas, a credit risk analyst at Rand Merchant Bank in Johannesburg, said by phone. Growth will slow to 3.4 percent in 2015, missing the government’s revised target of 5 percent, Barclays Plc said in a note last week. That would be the most sluggish pace since 2001.

The looming debt crisis will hit Zambia and other commodity exporters hard. As I noted two years ago, the vast majority of the African countries that have floated dollar-denominated bonds are heavily dependent on commodity exports. Many of them are already experiencing fiscal blues on account of the global commodity slump (see for example Angola, Zambia and Ghana). This will probably get worse. And the double whammy of plummeting currencies and reduced commodity exports will increase the real cost of external debt (on top of fueling domestic inflation). I do not envy African central bankers.

Making sure that the looming debt crises do not result in a disastrous retrenchment of the state in Africa, like happened in the 1980s and 1990s, is perhaps the biggest development challenge of our time. Too bad all the attention within the development community is focused elsewhere.

Africa's looming debt crises

Prince Akeem

Its not that deep breh....

Map: China’s Stereotypes of Africa, from ‘Chaotic’ Somalia to ‘Awesome’ Gambia

They don't differ materially from American views of the continent.

China’s ambitions in Africa are well-documented. Its annual trade with the resource-rich continent recently surpassed $200 billion, and Chinese agencies and firms have invested heavily in building badly needed roads, railways, and public buildings. Meanwhile, more than 1 million Chinese have reportedly left home to seek their fortunes in African nations.

Those ties may be drawing China and Africa closer, but that doesn’t mean everyday Chinese understand the continent terribly well. For example: “Why does South Africa have so many white people?” is the leading autocompleted result for queries about that country posed to Baidu, China’s largest search engine. Baidu’s autocomplete feature works similar to Google’s: When someone begins typing into the search box, an algorithm displays a list of suggested ways to finish the query, in part by combing the engine’s archives for previously popular searches. Those automatic suggestions often have the added benefit of sifting through layers of online discourse to uncover the profound and (often amusingly) mundane questions that often lead people to search for answers.

Below, Foreign Policy plots and translates the most common Chinese-language Baidu query associated with each African country onto the map below:

The leading queries for many African countries indicate that Chinese web users’ feelings about the continent mirror those of Westerners — they often associate it with violence, poverty, disease, and exotic dining habits. This is evident in country-by-country results but also is clear in searches about Africa as a whole:

Certain results are uniquely Chinese. Baidu’s top suggestion for Egypt asks why that country is more ancient than China, indicating that the pride with which Chinese people compare their civilization’s long history to that of Europe, and especially to that of the United States, wilts somewhat in the shadow of the pyramids at Giza.

Issues handed down by Africa’s complicated history top the results for other countries as well. Netizens ask how Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana came to be known as Ivory Coast and Gold Coast, respectively. Queries about Algeria and Libya being attacked by French and U.S. forces hint at Western interventions old and new. And then there is the legacy of imperialism, apartheid, and reconciliation that accounts for the prevalence of Caucasians in Africa’s “rainbow nation.”

Perhaps the most puzzling result from either method simply asks why Gambians are so “nb” — an abbreviation of niubi, a Chinese slang term that loosely translates as a sarcastic spin on “awesome” (but which, in fact, means something far more vulgar). This search leads to multiple bulletin boards bearing a list of purported threats by the tiny West African nation to variously invade and occupy the Soviet Union, North America, and most of Europe, as well as help Taiwan complete its reconquista of the Chinese mainland. FP was unable to verify these claims independently, though in fairness they don’t sound out of place given past proclamations by the country’s colorful leader.

Searches about violence sometimes take on a Chinese twist with the word luan — usually translated as “chaos,” a freighted word often used to connote political and social instability. References to luan crop up in results for South Africa, but are most common in those of Somalia. Netizens also ask why what the Economist called“the world’s most utterly failed state,” Somalia, has no government, why it hates America, and why it has pirates.

On a lighter note, searches about soccer are common. The “African Lions” that top Cameroon’s suggested searches refers to that country’s national football team. Baidu also notes that Nigeria’s team is called the “Eagles,” though that search is dwarfed by multiple queries about that country’s brief ban from international competition last year. Recent headlines also inspired a leading result for the Central African Republic, where sectarian strife led to acts of cannibalism.

The methodology involved typing the question prompt “Why is [country X]…,” though limited results for some countries led in a few cases to FP’s casting a wider net by simply typing the country’s name to see what connections Baidu would autocomplete. This approach yields the out-of-left-field results for Madagascar, Burundi (a species of fish native to a local lake), and Sudan (the seeds of a local variety of sorghum), among a handful of others. This more open-ended method succeeded in generating the results for every country, although the map above does not plot countries that only yielded results common to many nations, including references to tourism, travel expenses, business visas, and the cost of freight. Searches to populate this map were conducted from a computer in Shanghai between Aug. 14 and Aug. 17, and results tend to change over time, so readers may not be able to replicate them precisely.

Map: China’s Stereotypes of Africa, from ‘Chaotic’ Somalia to ‘Awesome’ Gambia

They don't differ materially from American views of the continent.

- BY WARNER BROWN

- SEPTEMBER 30, 2015

-

China’s ambitions in Africa are well-documented. Its annual trade with the resource-rich continent recently surpassed $200 billion, and Chinese agencies and firms have invested heavily in building badly needed roads, railways, and public buildings. Meanwhile, more than 1 million Chinese have reportedly left home to seek their fortunes in African nations.

Those ties may be drawing China and Africa closer, but that doesn’t mean everyday Chinese understand the continent terribly well. For example: “Why does South Africa have so many white people?” is the leading autocompleted result for queries about that country posed to Baidu, China’s largest search engine. Baidu’s autocomplete feature works similar to Google’s: When someone begins typing into the search box, an algorithm displays a list of suggested ways to finish the query, in part by combing the engine’s archives for previously popular searches. Those automatic suggestions often have the added benefit of sifting through layers of online discourse to uncover the profound and (often amusingly) mundane questions that often lead people to search for answers.

Below, Foreign Policy plots and translates the most common Chinese-language Baidu query associated with each African country onto the map below:

The leading queries for many African countries indicate that Chinese web users’ feelings about the continent mirror those of Westerners — they often associate it with violence, poverty, disease, and exotic dining habits. This is evident in country-by-country results but also is clear in searches about Africa as a whole:

Certain results are uniquely Chinese. Baidu’s top suggestion for Egypt asks why that country is more ancient than China, indicating that the pride with which Chinese people compare their civilization’s long history to that of Europe, and especially to that of the United States, wilts somewhat in the shadow of the pyramids at Giza.

Issues handed down by Africa’s complicated history top the results for other countries as well. Netizens ask how Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana came to be known as Ivory Coast and Gold Coast, respectively. Queries about Algeria and Libya being attacked by French and U.S. forces hint at Western interventions old and new. And then there is the legacy of imperialism, apartheid, and reconciliation that accounts for the prevalence of Caucasians in Africa’s “rainbow nation.”

Perhaps the most puzzling result from either method simply asks why Gambians are so “nb” — an abbreviation of niubi, a Chinese slang term that loosely translates as a sarcastic spin on “awesome” (but which, in fact, means something far more vulgar). This search leads to multiple bulletin boards bearing a list of purported threats by the tiny West African nation to variously invade and occupy the Soviet Union, North America, and most of Europe, as well as help Taiwan complete its reconquista of the Chinese mainland. FP was unable to verify these claims independently, though in fairness they don’t sound out of place given past proclamations by the country’s colorful leader.

Searches about violence sometimes take on a Chinese twist with the word luan — usually translated as “chaos,” a freighted word often used to connote political and social instability. References to luan crop up in results for South Africa, but are most common in those of Somalia. Netizens also ask why what the Economist called“the world’s most utterly failed state,” Somalia, has no government, why it hates America, and why it has pirates.

On a lighter note, searches about soccer are common. The “African Lions” that top Cameroon’s suggested searches refers to that country’s national football team. Baidu also notes that Nigeria’s team is called the “Eagles,” though that search is dwarfed by multiple queries about that country’s brief ban from international competition last year. Recent headlines also inspired a leading result for the Central African Republic, where sectarian strife led to acts of cannibalism.

The methodology involved typing the question prompt “Why is [country X]…,” though limited results for some countries led in a few cases to FP’s casting a wider net by simply typing the country’s name to see what connections Baidu would autocomplete. This approach yields the out-of-left-field results for Madagascar, Burundi (a species of fish native to a local lake), and Sudan (the seeds of a local variety of sorghum), among a handful of others. This more open-ended method succeeded in generating the results for every country, although the map above does not plot countries that only yielded results common to many nations, including references to tourism, travel expenses, business visas, and the cost of freight. Searches to populate this map were conducted from a computer in Shanghai between Aug. 14 and Aug. 17, and results tend to change over time, so readers may not be able to replicate them precisely.

Map: China’s Stereotypes of Africa, from ‘Chaotic’ Somalia to ‘Awesome’ Gambia

Labadi_Mantse

All Star

Map: China’s Stereotypes of Africa, from ‘Chaotic’ Somalia to ‘Awesome’ Gambia

They don't differ materially from American views of the continent.

- BY WARNER BROWN

- SEPTEMBER 30, 2015

China’s ambitions in Africa are well-documented. Its annual trade with the resource-rich continent recently surpassed $200 billion, and Chinese agencies and firms have invested heavily in building badly needed roads, railways, and public buildings. Meanwhile, more than 1 million Chinese have reportedly left home to seek their fortunes in African nations.

Those ties may be drawing China and Africa closer, but that doesn’t mean everyday Chinese understand the continent terribly well. For example: “Why does South Africa have so many white people?” is the leading autocompleted result for queries about that country posed to Baidu, China’s largest search engine. Baidu’s autocomplete feature works similar to Google’s: When someone begins typing into the search box, an algorithm displays a list of suggested ways to finish the query, in part by combing the engine’s archives for previously popular searches. Those automatic suggestions often have the added benefit of sifting through layers of online discourse to uncover the profound and (often amusingly) mundane questions that often lead people to search for answers.

Below, Foreign Policy plots and translates the most common Chinese-language Baidu query associated with each African country onto the map below:

The leading queries for many African countries indicate that Chinese web users’ feelings about the continent mirror those of Westerners — they often associate it with violence, poverty, disease, and exotic dining habits. This is evident in country-by-country results but also is clear in searches about Africa as a whole:

Certain results are uniquely Chinese. Baidu’s top suggestion for Egypt asks why that country is more ancient than China, indicating that the pride with which Chinese people compare their civilization’s long history to that of Europe, and especially to that of the United States, wilts somewhat in the shadow of the pyramids at Giza.

Issues handed down by Africa’s complicated history top the results for other countries as well. Netizens ask how Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana came to be known as Ivory Coast and Gold Coast, respectively. Queries about Algeria and Libya being attacked by French and U.S. forces hint at Western interventions old and new. And then there is the legacy of imperialism, apartheid, and reconciliation that accounts for the prevalence of Caucasians in Africa’s “rainbow nation.”

Perhaps the most puzzling result from either method simply asks why Gambians are so “nb” — an abbreviation of niubi, a Chinese slang term that loosely translates as a sarcastic spin on “awesome” (but which, in fact, means something far more vulgar). This search leads to multiple bulletin boards bearing a list of purported threats by the tiny West African nation to variously invade and occupy the Soviet Union, North America, and most of Europe, as well as help Taiwan complete its reconquista of the Chinese mainland. FP was unable to verify these claims independently, though in fairness they don’t sound out of place given past proclamations by the country’s colorful leader.

Searches about violence sometimes take on a Chinese twist with the word luan — usually translated as “chaos,” a freighted word often used to connote political and social instability. References to luan crop up in results for South Africa, but are most common in those of Somalia. Netizens also ask why what the Economist called“the world’s most utterly failed state,” Somalia, has no government, why it hates America, and why it has pirates.

On a lighter note, searches about soccer are common. The “African Lions” that top Cameroon’s suggested searches refers to that country’s national football team. Baidu also notes that Nigeria’s team is called the “Eagles,” though that search is dwarfed by multiple queries about that country’s brief ban from international competition last year. Recent headlines also inspired a leading result for the Central African Republic, where sectarian strife led to acts of cannibalism.

The methodology involved typing the question prompt “Why is [country X]…,” though limited results for some countries led in a few cases to FP’s casting a wider net by simply typing the country’s name to see what connections Baidu would autocomplete. This approach yields the out-of-left-field results for Madagascar, Burundi (a species of fish native to a local lake), and Sudan (the seeds of a local variety of sorghum), among a handful of others. This more open-ended method succeeded in generating the results for every country, although the map above does not plot countries that only yielded results common to many nations, including references to tourism, travel expenses, business visas, and the cost of freight. Searches to populate this map were conducted from a computer in Shanghai between Aug. 14 and Aug. 17, and results tend to change over time, so readers may not be able to replicate them precisely.

Map: China’s Stereotypes of Africa, from ‘Chaotic’ Somalia to ‘Awesome’ Gambia

Interesting

The Odum of Ala Igbo

Hail Biafra!

Agriculture in Africa

Wake up and sell more coffee

Small farmers in Africa need to produce more. Happily that is easier than it sounds

ON A hillside about an hour’s drive north of Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, is a visible demonstration of the difference between the miserable reality of smallholder farming in Africa and what it could be. On one side of the steep terraces stand verdant bushes, their stems heavy with plump coffee beans. A few feet away are sickly ones, their sparse leaves spotted with disease and streaked with yellow because of a lack of fertiliser.

Millicent Wanjiku Kuria, a middle-aged widow, beams under an orange headcloth. Cash from coffee has already allowed her to buy more land and a cutting machine that prepares fodder for a dairy cow that lows softly in its thatched shed. Her bumper crops are largely a result of better farming techniques such as applying the right amount of fertiliser (two bags, not one) and pruning back old stems on her trees. Simple changes such as these can increase output by 50% per tree. Her income has increased by even more than this, because bigger berries from healthy trees sell at twice the price of their scrawnier brethren, says Arthur Nganga of TechnoServe, a non-profit group that is training Mrs Kuria and thousands of other smallholders in Kenya, Ethiopia and South Sudan. This year’s crop will pay for a pickup, she says, so she no longer has to hitch rides on a motorcycle.

Mrs Kuria’s success invites a question. If it is so easy to raise a small farmer’s output, why haven’t all the small farmers managed it? To say that the answer matters is a wild understatement. Africa’s poorest and hungriest people are nearly all farmers. To lift themselves out of poverty, they must either move to a city or learn to farm better.

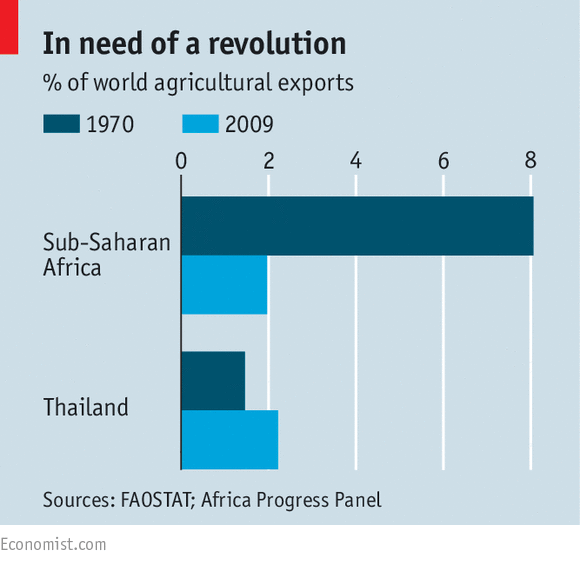

It should be possible to grow much more in Africa. The continent has about half of the world’s uncultivated arable land and plenty of people to work it. It is true that erratic rainfall adds to the risks of farming on large parts of the savannah, but switching to drought-tolerant varieties of plants or even to entirely different ones—cassava or sorghum instead of maize, for instance—can mitigate much of this problem. Indeed Africa has in the past given glimpses of its vast potential. Five decades ago it was one of the world’s great crop-exporters. Ghana grew most of the world’s cocoa, Nigeria was the biggest exporter of palm oil and peanuts, and Africa grew a quarter of all the coffee people slurped.

Since then it has shifted from being a net exporter of food to an importer. Sub-Saharan Africa’s share of agricultural exports has slipped to a quarter of its previous level; indeed, the entire region has been overtaken by a single country: Thailand (see chart). This is largely because Africa’s crop yields have improved at only half the pace of those elsewhere and are now, on average, a third to a half of those in the rich world. Farmers in Malawi harvest just 1.3 tonnes of maize per hectare compared with 10 tonnes in Iowa.

There are several reasons for the stagnation in African agricultural productivity but poor policies have played a large role. In many countries state-owned monopolies for the main export crops were established either before independence or soon after. The prices paid to farmers were generally squeezed to create profits that were meant to be invested in other, sexier, industries. Such policies failed to spark an industrial revolution but succeeded in making farmers poorer. In Ghana, for instance, the colonial administration and first independent government taxed cocoa exports so heavily that farmers stopped planting new trees. By the 1980s cocoa production had collapsed by two-thirds.

In the 1990s many of these policy mistakes were compounded when, urged on by Western donors and aid experts, many African countries dismantled their agricultural monopolies without giving time for markets to develop or putting in place institutions to link farmers to them. This was good for commercial farmers in places such as South Africa, where output soared, but cut off remote smallholders. Farmers in Zambia, for instance, now pay twice as much for fertiliser as those in America.

Yet this Cinderella sector is now being seen as an opportunity rather than a “development problem”, says Mamadou Biteye, who heads the African operations of the Rockefeller Foundation, a charity. Money from organisations such as Rockefeller, the Gates Foundation and do-gooding companies such as Nestlé is pouring into supporting small farmers.

The first benefit is improved productivity. Farmers have been shown how to increase crop yields sharply simply by changing their techniques or switching to better plant varieties. A second is in improving farmers’ access to markets. Progress here is being speeded along by technology. In Nigeria the government has stopped distributing subsidised fertiliser and seeds through middlemen who generally pocketed the subsidies: it reckons that only 11% of farmers actually got the handouts that were earmarked for them. Instead it now directly issues more than 14m farmers with electronic vouchers via mobile phones.

Or take Kenya Nut, a privately owned nut processor. It is using technology from the Connected Farmer Alliance to send text messages to farmers giving them the market price of their produce, so they are not ripped off by the first buyer to show up with a lorry.

After years of underperforming, Africa’s smallholders have a lot of catching up to do. The World Bank estimates that food production and processing in Africa could generate $1 trillion a year by 2030, up from some $300 billion today. Yet many remain sceptical that Africa’s small farmers will achieve their potential. To some, the rewards on offer seem too good to be true, like the $50 on the pavement that the economist in the joke walks past because “If it were real, someone would already have picked it up.”

Yet the success of projects such as those run by TechnoServe and Olam (a commodity trader that helps farmers grow more cashews, sesame seeds and cocoa in Nigeria) suggest that there may well be $700 billion on the pavement—or rather, in Africa’s fields. Instead of subsidising steel and other big industries, African nations should wake up and sell more coffee—not to mention cocoa, nuts and maize.

From the print edition: Middle East and Africa

http://www.economist.com/news/middl...?fsrc=scn/tw/te/pe/ed/wakeupandsellmorecoffee

Let's face the facts. While Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia came to support their farmers - African leaders like Nkrumah just thought farmers were in the way of industrial progres in Africa. So, they squeezed African farmers a little like how Stalin squeezed peasants in the Soviet Union. When their parastatal industrialization failed, the invisible hands of the IMF/World Bank crushed any gov't run structures that could've helped farmers such as cocoa marketing boards. It's not too late but the damage has been done.

The Odum of Ala Igbo

Hail Biafra!

Dangote is trying to corner Africa's cement market. It's a very admirable endeavour. I wish him luck. Meanwhile, in the Horn of Africa...

Bullish Ethiopia and Djibouti agree on $1.55Bn pipeline; Kenya’s LAPSSET has reason to worry

Bullish Ethiopia and Djibouti agree on $1.55Bn pipeline; Kenya’s LAPSSET has reason to worry

Bullish Ethiopia and Djibouti agree on $1.55Bn pipeline; Kenya’s LAPSSET has reason to worry

30 Sep 2015 20:15Bloomberg, AFP, M&G Africa

LinkedIn4Twitter55Google+Facebook193Email

Ethiopia and Djibouti are looking to create an African infrastructure hegemony that reaches into West Africa.

THE MEN IN NAVY BLUE: Ethiopian Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn with Djibouti President, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh. If they had their way they would own oil the railway and oil pipelines from East Africa to the Gulf of Guinea. (Photo/AFP).

ETHIOPIA and neighbour Djibouti signed an agreement for a $1.55 billion fuel pipeline with developers Mining, Oil & Gas Services and Blackstone Group LP-backed Black Rhino Group.

The two countries in the Horn of Africa signed framework agreements on Tuesday for construction of the 550-kilometer (340-mile) line to transport diesel, gasoline and jet fuel from port access in Djibouti to central Ethiopia, the companies said. Financial close is expected in 2016, with construction scheduled for completion two years later.

Growth in landlocked Ethiopia has surpassed every other sub-Saharan country over the past decade, and the government has boosted spending to expand infrastructure. Fuel is typically delivered by tanker truck.

“The pipeline will increase energy security, aid economic development and reduce harmful emissions,” Black Rhino Chief Executive Officer Brian Herlihy said in the statement. The 50-50 joint venture with MOGS, a unit of Johannesburg-based Royal Bafokeng Holdings, will seek to raise at least $1 billion of senior debt financing.

The project, known as the Horn of Africa Pipeline, includes an import facility and 950,000 barrels of storage capacity in Damerjog, Djibouti, linked to a storage terminal in Awash, Ethiopia.

The 20-inch (51-centimetre) line is capable of transporting 240,000 barrels a day of fuel. The concession period after commercial operations start is for as many as 30 years.

Looking to conquer

Ethiopia and Djibouti have invested heavily in joint infrastructure, in a bid to make the make the Ethiopia-Djibouti belt the logistics hub of the continent in the long-term, but more immediately for the wider East and Central Africa.

In the meantime, both countries benefit from economic integration, with Ethiopia gaining access to the sea and Djibouti gaining

Nearly 99% of imports from fast-growing Ethiopia pass through its neighbour, in June the two countries oversaw the completion of a railway linking their two capitals Addis Ababa and Djibouti.

(READ: Hurray! Gamechanger Djibouti-Ethiopia railway ready, will cut goods travel time from two days to 10 hours).

The ambition is that the link might eventually extend across the continent to West Africa.

Djibouti’s President Ismail Omar Guelleh and Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn attended the ceremonial laying of the last track in the 752-kilometre (481-mile) railway, financed and built by China.

The first scheduled train is expected to use the desert line in October, reducing transport time between the capitals to less than 10 hours, rather than the two days it currently takes for heavy goods vehicles using a congested mountain road.

Another new line linking Djibouti and the northern Ethiopian town of Mekele is also due to be built, but this is not the extent of the project’s ambition.

Djibouti, the smallest state in the Horn of Africa, is embarking on large infrastructure projects, building six new ports and two airports in the hope of becoming the commercial hub of East Africa.

The Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway will be completed in a few days: Its architects see it is a step towards a trans-continental line reaching all the way to West Africa. (Photo/AFP).

Indicative of the strategic thinking of Djibouti, Abubaker Hadi, chairman of Djibouti Port Authority, said in June that therailway is a step towards a trans-continental line reaching all the way to the Gulf of Guinea, in West Africa.

“We are already the gateway to Ethiopia. We intend to continue this railway line to South Sudan, the Central African Republic (CAR) and Cameroon to connect the Red Sea to the Atlantic Ocean,” said Hadi.

Djibouti, the smallest state in the Horn of Africa, is embarking on large infrastructure projects, building six new ports and two airports in the hope of becoming the commercial hub of East Africa.

“Infrastructure is coming very late to Africa. It is impossible for a truck to cross the continent. To transport goods from the east coast to the west coast of Africa, it is necessary to circle the continent by boat,” Hadi said of a sea voyage that can take more than three weeks. A trans-Africa railway is feasible “in seven or eight years,” he said, as long as conflicts in South Sudan and CAR come to an end.

“Infrastructure is coming very late to Africa. It is impossible for a truck to cross the continent. To transport goods from the east coast to the west coast of Africa, it is necessary to circle the continent by boat,” Hadi said of a sea voyage that can take more than three weeks.

A trans-Africa railway is feasible “in seven or eight years,” he said, as long as conflicts in South Sudan and the Central African Republic Republic (CAR) come to an end.

Hurry up for Kenya

The reference to the conflict in South Sudan is significant, because it is seen as one of the reasons for a similar project in which Ethiopia signed up to; the Lamu Port Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor.

LAPSSET is the Kenyan government’s biggest infrastructure project. It envisages the construction of a port, power plant, railway and other facilities from the Lamu port, through to South Sudan and Ethiopia.

A desalination plant will also be built in Lamu to address water shortages in the area.

Kenya’s Treasury has estimated the Lapsset project will cost $26 billion. East Africa’s largest economy envisages also building resort cities, an international airport and an inter-regional highway, according to the government’s website.

However, LAPSSET has been hit by delay and security problems. Lamu borders Somalia, where the al-Qaeda-linked militants have waged an insurgency since 2006.

They’ve also carried out raids along Kenya’s coast, including one in Mpeketoni, near Lamu, in June 2014 in which at least 60 people died.

The national government has taken measures to improve security in the area, including starting construction of a border fence.

The deadly new war in South Sudan, the world’s youngest nation, that broke out in December 2013 following a political fall-out between President Salva Kiir and his former deputy Riek Machar, took another layer of shine over the project.

It is not clear if the Djibouti-Ethiopia pipeline will affect Addis Ababa’s interest in LAPSSET. In all likelihood, it will be completed as it’s not affected by Somalia and South Sudan instability.

Perhaps aware that not everyone would wait, Kenya is frantically trying to jumpstart the project.

(READ: Kenya, U.S. firms in talks on mega $26 billion Lamu Port Southern Sudan-Ethiopia deal).

In July, it was reported that Kenyan and U.S. companies were negotiating a potential multibillion-dollar agreement with the Kenyan government to help develop LAPSSET.

Discussions were led by Aeolus Kenya Ltd., a closely held power and infrastructure developer known as AKL, he said in a phone interview on July 21.

The group of U.S. companies interested in the project, includes Bechtel Group Inc.

Discussions about the deal coincided with U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit to Kenya.

Ikhide Ikheloa: Corruption is not stealing in Nigeria

Posted By TheScoop on October 1, 2015

0 Pa Ikhide

By Ikhide Ikheloa

Corruption is not stealing in Nigeria. That is what the great visionary, Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, former president of Nigeria once said in a moment of inebriated inspiration.

He is right. Our people say it is what is in your mind when you are sober that comes trotting out when you are drunk on Orijin. Nigeria is not yet officially a rogue state but corruption is our way of life. It is the truth: If the punishment for corruption in Nigeria was the death penalty, we would all lose all our friends, our relatives – and our lives. Steal a banana in the market place and Nigerians will light you up and burn you to death. Get a job with the government and you refuse to be corrupt and Nigerians will light you up and burn you to death. Corruption is in Nigerians’ cultural and social genes, it’s the currency of all transactions. Stop it, yes but replace it with new currency.

Corruption is Nigeria’s primary infrastructure for getting anything done. The cellphone is right behind it in its ubiquity and utility. Corruption is Nigeria’s official currency, followed by the almighty dollar. Without corruption, modern Nigeria would grind to a fast shrieking halt. Corruption, official graft is Nigeria’s truly functioning mechanism for revenue allocation and business generation, the only taxation system that works.

Corruption is how we sustain ancient dysfunctions like the extended family system. The extended family system in the 21st century is an expensive and ultimately unsustainable enterprise – and like American capitalism can only be sustained by throwing loot at it.

Kill graft and if you don’t replace it with sustainable processes you have killed Nigeria. Go to any funeral or wedding and you will see that our politicians are the least of our problems. We are the problem. No one in Nigeria can and should survive on honesty and a paycheck, it is a structural problem. We all know many civil servants who don’t know how much they are paid. They survive almost exclusively from the proceeds of corruption. And they get away with it. Indeed, the only Nigerian that ever went to jail on account of Corruption was Obi Okonkwo in Chinua Achebe’s epic book No Longer at Ease. And that was fiction.

Soon, Nigeria will make honesty a crime punishable by death through hunger. Wait, it is already a crime. I do not know of any Nigerian alive that has not benefitted from corruption, not one.

Seriously, we have a problem, outside of America, no nation has been known to survive bearing corruption on its back. Our rulers are corrupt, government is a sick, corrupt hyena that keeps taking and taking and giving back nothing but grief. How do we get rid of our problem? What is the alternative? I have a brilliant idea. Walmart! Walmart! Walmart? Yes, we should outsource government to Walmart, the big American store, that ode to mindless consumerism! Yes. I love Walmart; it is a soulless place where you can pretend that the crap you are buying is a bargain. Walmart is capitalism baring its mean fangs at the dispossessed. But the sale of the soul is cheap. Walmart is the faux equalizer. Everything there is fake. Just like the originals they mimic.

I don’t know of any Nigerian that has the moral authority to lecture against Walmart coming to Nigeria. Those that go to Dubai daily to prop up the mother of all capitalistic excess wish to deny my mother access to Walmart. Those that steal Nigeria blind every day wish to lecture us on the new invasion. Those that refuse to teach our children, those who “teach” our children while their own children go to $60,000 a year universities abroad, wish to lecture us about the dangers of importation of all kinds of alien cultures and influences into Nigeria. It sounds patronizing; our people may be poor but they are perfectly sane and smart enough to choose between a Chinese calabash and an American calabash.

Walmart will bring water, roads and light to Nigeria. I say to Walmart, make my prophecy real; bring your big stores and sell us what the government du jour refuses to give us after stripping us of our money – roads, hospitals, schools, safety and security. Walmart, build a road for us, from my village to the big cities, a road that can take your big 18-wheerlers, a real road. And bring light that will last 24/7. And bring water to my village. Why, the rusty pumps in my village last worked in 1956 when the oil pumps started working in Oloibiri. You can do it. Ignore my thieving brothers and sisters. Did they not steal every penny that was budgeted for the roads? Did they not steal every penny that was budgeted for water, for light? Why do you think pot-bellied generals are fleeing Boko Haram? They stole the money meant for weapons. Walmart, come to Nigeria, to sell us good governance. On aisle 419. Just like the cell phones saved us from NITEL. I cannot wait for the second colonialism.

Obi Okonkwo? You don’t know him? You mean you have never read Achebe’s No Longer at Ease? Well, shame on you. Things did not end well for Obi Okonkwo in that lovely book. He left the shores of Nigeria as a black man, went to school in England and was raised in the ways of the white man and came back as a black white man. His clan, the members of the extended family that raised him and sent him to England did not understand this new person that hugged himself close and was reticent about doing whatever it took to take care of the clan. Eventually he succumbed to the call of the land, to help those who had scraped pennies together to train him. It was an expensive undertaking as a civil servant; he could not support his extended family on his income. He succumbed to the lure of corruption to satisfy his clan. And the white man sent him to jail. That was before Independence. The white man came with his accountability measures and left with them. Yup, Obi Okonkwo was the first and the last civil servant to go to jail in Nigeria. And that was fiction. Yup. Welcome to Nigeria.

Posted By TheScoop on October 1, 2015

0 Pa Ikhide

By Ikhide Ikheloa

Corruption is not stealing in Nigeria. That is what the great visionary, Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, former president of Nigeria once said in a moment of inebriated inspiration.

He is right. Our people say it is what is in your mind when you are sober that comes trotting out when you are drunk on Orijin. Nigeria is not yet officially a rogue state but corruption is our way of life. It is the truth: If the punishment for corruption in Nigeria was the death penalty, we would all lose all our friends, our relatives – and our lives. Steal a banana in the market place and Nigerians will light you up and burn you to death. Get a job with the government and you refuse to be corrupt and Nigerians will light you up and burn you to death. Corruption is in Nigerians’ cultural and social genes, it’s the currency of all transactions. Stop it, yes but replace it with new currency.

Corruption is Nigeria’s primary infrastructure for getting anything done. The cellphone is right behind it in its ubiquity and utility. Corruption is Nigeria’s official currency, followed by the almighty dollar. Without corruption, modern Nigeria would grind to a fast shrieking halt. Corruption, official graft is Nigeria’s truly functioning mechanism for revenue allocation and business generation, the only taxation system that works.

Corruption is how we sustain ancient dysfunctions like the extended family system. The extended family system in the 21st century is an expensive and ultimately unsustainable enterprise – and like American capitalism can only be sustained by throwing loot at it.

Kill graft and if you don’t replace it with sustainable processes you have killed Nigeria. Go to any funeral or wedding and you will see that our politicians are the least of our problems. We are the problem. No one in Nigeria can and should survive on honesty and a paycheck, it is a structural problem. We all know many civil servants who don’t know how much they are paid. They survive almost exclusively from the proceeds of corruption. And they get away with it. Indeed, the only Nigerian that ever went to jail on account of Corruption was Obi Okonkwo in Chinua Achebe’s epic book No Longer at Ease. And that was fiction.

Soon, Nigeria will make honesty a crime punishable by death through hunger. Wait, it is already a crime. I do not know of any Nigerian alive that has not benefitted from corruption, not one.

Seriously, we have a problem, outside of America, no nation has been known to survive bearing corruption on its back. Our rulers are corrupt, government is a sick, corrupt hyena that keeps taking and taking and giving back nothing but grief. How do we get rid of our problem? What is the alternative? I have a brilliant idea. Walmart! Walmart! Walmart? Yes, we should outsource government to Walmart, the big American store, that ode to mindless consumerism! Yes. I love Walmart; it is a soulless place where you can pretend that the crap you are buying is a bargain. Walmart is capitalism baring its mean fangs at the dispossessed. But the sale of the soul is cheap. Walmart is the faux equalizer. Everything there is fake. Just like the originals they mimic.

I don’t know of any Nigerian that has the moral authority to lecture against Walmart coming to Nigeria. Those that go to Dubai daily to prop up the mother of all capitalistic excess wish to deny my mother access to Walmart. Those that steal Nigeria blind every day wish to lecture us on the new invasion. Those that refuse to teach our children, those who “teach” our children while their own children go to $60,000 a year universities abroad, wish to lecture us about the dangers of importation of all kinds of alien cultures and influences into Nigeria. It sounds patronizing; our people may be poor but they are perfectly sane and smart enough to choose between a Chinese calabash and an American calabash.

Walmart will bring water, roads and light to Nigeria. I say to Walmart, make my prophecy real; bring your big stores and sell us what the government du jour refuses to give us after stripping us of our money – roads, hospitals, schools, safety and security. Walmart, build a road for us, from my village to the big cities, a road that can take your big 18-wheerlers, a real road. And bring light that will last 24/7. And bring water to my village. Why, the rusty pumps in my village last worked in 1956 when the oil pumps started working in Oloibiri. You can do it. Ignore my thieving brothers and sisters. Did they not steal every penny that was budgeted for the roads? Did they not steal every penny that was budgeted for water, for light? Why do you think pot-bellied generals are fleeing Boko Haram? They stole the money meant for weapons. Walmart, come to Nigeria, to sell us good governance. On aisle 419. Just like the cell phones saved us from NITEL. I cannot wait for the second colonialism.

Obi Okonkwo? You don’t know him? You mean you have never read Achebe’s No Longer at Ease? Well, shame on you. Things did not end well for Obi Okonkwo in that lovely book. He left the shores of Nigeria as a black man, went to school in England and was raised in the ways of the white man and came back as a black white man. His clan, the members of the extended family that raised him and sent him to England did not understand this new person that hugged himself close and was reticent about doing whatever it took to take care of the clan. Eventually he succumbed to the call of the land, to help those who had scraped pennies together to train him. It was an expensive undertaking as a civil servant; he could not support his extended family on his income. He succumbed to the lure of corruption to satisfy his clan. And the white man sent him to jail. That was before Independence. The white man came with his accountability measures and left with them. Yup, Obi Okonkwo was the first and the last civil servant to go to jail in Nigeria. And that was fiction. Yup. Welcome to Nigeria.

mbewane

Knicks: 93 til infinity

I need to consult this thread more often

Malawi, Zambia Seek Trade Waterway to Mozambique

News / Africa

Malawi, Zambia Seek Trade Waterway to Mozambique

Lameck Masina

October 01, 2015 12:50 PM

BLANTYRE, MALAWI—Mozambique continues to resist work to reopen a waterway that would give Zambia and Malawi, both landlocked countries, access to its Chinde port on the Indian Ocean. The route hasn't been in use since the 1970s when civil war erupted in Mozambique. Reopening it could be a major boom to Malawi and Zambia's economies.

The Malawian government spends $300 million annually to import and export goods. Much of that trade moves through the ports of Beira and Nacala in neighboring Mozambique.

That means goods must travel by rail, as far as 1,200 kilometers.

Traders are loading bags of cement at Wenela railway station in Blantyre heading to the southern district of Balaka. The cement arrived via Mozambique.

Mayamiko Majawa, one of the traders, said erratic train schedules affect his business.

“We are supposed to transport the goods four times a week but the train only comes once a week. That is a very big problem in business because at least we could be selling more if we transported a lot of goods in a week,” said Majawa.

Shire-Zambezi waterway

Malawi and its neighbor, Zambia, want to reopen the Shire-Zambezi waterway with access to the Mozambican port of Chinde.

Proposing the move back in 2005, then Malawian president Bingu wa Mutharika said it would slash costs of doing business for Malawi by 60 percent.

But recent talks between the three countries in Malawi ended in deadlock.

Reopening the waterway would cost the governments and donors an estimated $6 billion.

Mozambique's Minister of Transport Carlos Mesquitta said it will be too expensive.

"Within 10 to 15 years, the cost of maintenance dredging per year will be doubled. So, double, means $60 million. So how come it says we will have some advantage and then we will be paralyzed by all sorts of these things?” he asked.

Chinde waterway

Mesquitta said the annual cargo load for Chinde – about 250,000 tons – is far less than the 15 million tons Mozambique loads through its three other ports.

But Zambia’s deputy minister of transport Mutaba Mwali said the waterway is worth it.

“We are in a position like Malawi. We are a land locked country. And we know that water transport offers the cheapest means of transport for our goods. So we are eager to see the fruits of this project," said Mwali.

Malawi said compromise is possible. Another round of talks on the waterway is planned for November in Zambia.

News / Africa

Malawi, Zambia Seek Trade Waterway to Mozambique

Lameck Masina

October 01, 2015 12:50 PM

BLANTYRE, MALAWI—Mozambique continues to resist work to reopen a waterway that would give Zambia and Malawi, both landlocked countries, access to its Chinde port on the Indian Ocean. The route hasn't been in use since the 1970s when civil war erupted in Mozambique. Reopening it could be a major boom to Malawi and Zambia's economies.

The Malawian government spends $300 million annually to import and export goods. Much of that trade moves through the ports of Beira and Nacala in neighboring Mozambique.

That means goods must travel by rail, as far as 1,200 kilometers.

Traders are loading bags of cement at Wenela railway station in Blantyre heading to the southern district of Balaka. The cement arrived via Mozambique.

Mayamiko Majawa, one of the traders, said erratic train schedules affect his business.

“We are supposed to transport the goods four times a week but the train only comes once a week. That is a very big problem in business because at least we could be selling more if we transported a lot of goods in a week,” said Majawa.

Shire-Zambezi waterway

Malawi and its neighbor, Zambia, want to reopen the Shire-Zambezi waterway with access to the Mozambican port of Chinde.

Proposing the move back in 2005, then Malawian president Bingu wa Mutharika said it would slash costs of doing business for Malawi by 60 percent.

But recent talks between the three countries in Malawi ended in deadlock.

Reopening the waterway would cost the governments and donors an estimated $6 billion.

Mozambique's Minister of Transport Carlos Mesquitta said it will be too expensive.

"Within 10 to 15 years, the cost of maintenance dredging per year will be doubled. So, double, means $60 million. So how come it says we will have some advantage and then we will be paralyzed by all sorts of these things?” he asked.

Chinde waterway

Mesquitta said the annual cargo load for Chinde – about 250,000 tons – is far less than the 15 million tons Mozambique loads through its three other ports.

But Zambia’s deputy minister of transport Mutaba Mwali said the waterway is worth it.

“We are in a position like Malawi. We are a land locked country. And we know that water transport offers the cheapest means of transport for our goods. So we are eager to see the fruits of this project," said Mwali.

Malawi said compromise is possible. Another round of talks on the waterway is planned for November in Zambia.

Nigeria's ex-oil minister Alison-Madueke arrested in London - sources

By By Julia Payne and Felix Onuah | Reuters – 11 hours ago

By By Julia Payne and Felix Onuah | Reuters – 11 hours ago

By Julia Payne and Felix Onuah

LAGOS/ABUJA (Reuters) - Nigeria's former oil minister Diezani Alison-Madueke was arrested in London on Friday, a source from Nigeria's presidency circle and another with links to her family said.

Alison-Madueke was minister from 2010 until May 2015 under former president Goodluck Jonathan, who was defeated by Muhammadu Buhari at the polls in March.

Buhari took office in May promising to root out corruption in Africa's most populous country, where few benefit from the OPEC member's enormous energy resources.

A police spokesman in London said he had no record of such an arrest. The National Crime Agency did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

But in a short statement on its website, the NCA said its International Corruption Unit had arrested five people across London on suspicion of bribery and corruption offences on Friday, without naming the suspects.

Nigerian media outlets, including Channels TV, said that Alison-Madueke had been granted bail after several hours in custody.

Reuters was unable to reach Alison-Madueke's personal assistant or a lawyer representing her. She has previously denied to Reuters any wrongdoing when questioned about missing public funds and graft allegations.

In a sign that the arrest had been coordinated with Nigerian authorities, the financial crimes unit sealed one of Alison-Madueke's houses in the upmarket Asokoro district in the capital Abuja, two security officials said.

During her time in office, former central bank governor Lamido Sanusi was sacked after he raised concern that tens of billions of dollars in oil revenues had not been remitted to state coffers by the government-run oil company NNPC between January 2012 and July 2013.

Ordinary Nigerians, tired of seeing no narrowing of the West African country's wealth gap, have been eagerly waiting to see the results of probes into the oil sector.

Buhari said on Sunday that the prosecution of those suspected of misappropriating the NNPC's revenue under past administrations would begin soon.

Getting tough on corruption would deflect criticism of Buhari for failing to appoint a cabinet or an economic team four months after taking office as Nigeria's economy is going through a severe crisis due to the plunge in global oil prices.

(Reporting by Felix Onuah and Julia Payne, additional reporting by UK newsroom; writing by Julia Payne and Ulf Laessing; editing by Janet Lawrence and G Crosse)

By By Julia Payne and Felix Onuah | Reuters – 11 hours ago

By By Julia Payne and Felix Onuah | Reuters – 11 hours ago-

View Photo

Reuters/Reuters - Nigeria's Petroleum Minister and OPEC's alternate president Diezani Alison-Madueke speaks at the annual IHS CERAWeek conference in Houston, Texas March 4, 2014. REUTERS/Rick Wilki …more

By Julia Payne and Felix Onuah

LAGOS/ABUJA (Reuters) - Nigeria's former oil minister Diezani Alison-Madueke was arrested in London on Friday, a source from Nigeria's presidency circle and another with links to her family said.

Alison-Madueke was minister from 2010 until May 2015 under former president Goodluck Jonathan, who was defeated by Muhammadu Buhari at the polls in March.

Buhari took office in May promising to root out corruption in Africa's most populous country, where few benefit from the OPEC member's enormous energy resources.

A police spokesman in London said he had no record of such an arrest. The National Crime Agency did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

But in a short statement on its website, the NCA said its International Corruption Unit had arrested five people across London on suspicion of bribery and corruption offences on Friday, without naming the suspects.

Nigerian media outlets, including Channels TV, said that Alison-Madueke had been granted bail after several hours in custody.

Reuters was unable to reach Alison-Madueke's personal assistant or a lawyer representing her. She has previously denied to Reuters any wrongdoing when questioned about missing public funds and graft allegations.

In a sign that the arrest had been coordinated with Nigerian authorities, the financial crimes unit sealed one of Alison-Madueke's houses in the upmarket Asokoro district in the capital Abuja, two security officials said.

During her time in office, former central bank governor Lamido Sanusi was sacked after he raised concern that tens of billions of dollars in oil revenues had not been remitted to state coffers by the government-run oil company NNPC between January 2012 and July 2013.

Ordinary Nigerians, tired of seeing no narrowing of the West African country's wealth gap, have been eagerly waiting to see the results of probes into the oil sector.

Buhari said on Sunday that the prosecution of those suspected of misappropriating the NNPC's revenue under past administrations would begin soon.

Getting tough on corruption would deflect criticism of Buhari for failing to appoint a cabinet or an economic team four months after taking office as Nigeria's economy is going through a severe crisis due to the plunge in global oil prices.

(Reporting by Felix Onuah and Julia Payne, additional reporting by UK newsroom; writing by Julia Payne and Ulf Laessing; editing by Janet Lawrence and G Crosse)

Married women and drugs, ‘a time bomb waiting to explode’

Married women and drugs, ‘a time bomb waiting to explode’

By Ruby Leo | Publish Date: Oct 1 2015 9:01PM | Updated Date: Oct 1 2015 10:07PM

Recently, there were reports that more number of married women are getting hooked on drugs at an alarming rate, a trend that will not augur well for their homes and families.

Mothers are supposed to be pillars of the home. They spend a lot of time with the children, shape and train them to be able to face the challenges of life. Now, imagine when such an important person is not in the right frame of mind to tackle her responsibilities and chores.

Ali Baba Mustapha, Assistant Superintendent in charge of exhibits at the Sokoto State Command of NDLEA, made this shocking revelation about the Nigerian married women’s growing addiction to codeine, recently, during the Jigawa Day celebration organised by indigenes of the state at the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto State.

He said that the ugly situation has caused a systematic breakdown of the African cultural heritage and traditions, leading to many forms of crimes being perpetrated by the youth.

Zainab Baba, a civil servant in Katsina, said that at her tender age, she used to see her mother smoke cigarette at night and some times in the day time when her father was not around.

She recalled that her mother, who would be somewhat agitated before the act, used to look calm after smoking a stick of cigarette and would then resume her chores.

According to her, it took her a while to realise that the act of smoking was not good for one’s health, saying: “Immediately I got married, I started smoking the same brand of cigarette my mother used to smoke whenever I was agitated or frustrated, to help calm my nerves.”

But using drugs or cigarettes to calm one’s nerves when under pressure is not the only reason why married women engage in the use of drugs, said Mustapha.

He claimed that these group of married women use codeine and other substance to enhance their sexual drive.

But Dr Vincent Udenze, a United Kingdom-based consultant psychiatrist and the Medical Director Synapse Services, revealed that most persons addicted to substances do so to forget some ordeal they suffered in their past or younger years, or their reality.

He added that most of the patients he has received in his facility, including married women, youths and adolescents started abusing drugs to cope with their friends.

He said: “What is most disturbing is the prevalence of married women who use substance, I mean drugs, both the subtle and the hard ones, and this is determined by their status. The kind of drugs they buy will be determined by how much they can afford at that time.

“Codeine is accessible and available and can be brought off the counter by anyone since these are not regulated. Some use heroin, cocaine, cannabis and, in most cases, they have agents who supply them the products for a fee, or they patronise joints where they buy them from touts.”

One of his clients, Mrs Gladys Ume (not real name), who is presently receiving treatment, said that she found succour in drinks, especially as things were not going quite well between her and her husband.

“Things are too hard, my kids and my husband don’t understand I need some time. Once I had a few minutes to myself, I took alcohol. Now, I can’t function without it, that’s why I am seeking help.”

Dr. Vincent Udenze also attributed the increasing rate of married women using drugs to the daily pressures they face at home, saying: “Some of these women have to cope with the travails of other wives, especially those married into polygamous homes and we know dealing with the demands of such homes can be quite an ordeal.

“Others are trying to just forget a past experience that has really scared them and made them not to enjoy their matrimonial home to the fullest, some who were sexually molested when they were young find it hard to allow intercourse with their spouse because it’s a constant reminder of the ordeal they went through.”