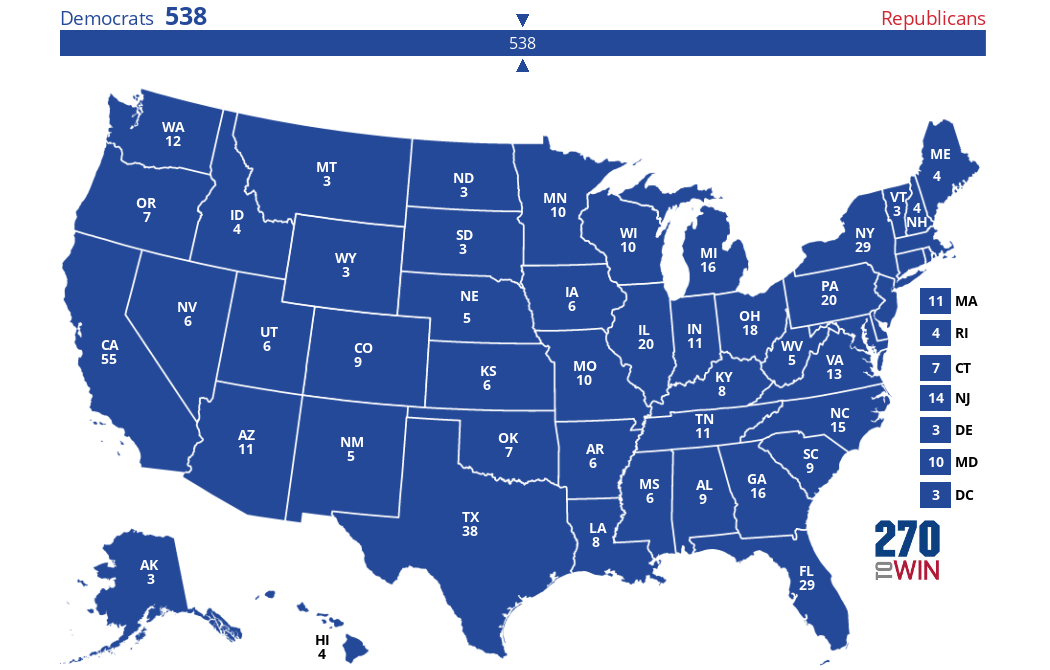

The state of the presidential race

When we

first debuted our 2020 Electoral College ratings way back in February 2019, we had a couple of ratings that we thought might raise eyebrows: We rated Michigan, Donald Trump’s closest victory in 2016, as Leans Democratic, and Florida, a state he won by just 1.2 points, as Leans Republican.

Our reasoning, in a nutshell, was that we thought Trump’s victory in Michigan was flukier than his wins anywhere else, and a better Democratic campaign effort in Michigan could be enough to flip the state. Meanwhile, we had just seen Democrats lose two statewide races, Senate and governor, in Florida in the midst of a 2018 midterm election where they had dominated many other purple states and districts. Trump had also generally polled a bit better in Florida than he had nationally throughout his presidency to that point.

At the time (Feb. 28, 2019), we wrote the following:

“Those who think we are being unfair to Trump by making Michigan Leans Democratic should consider whether we are perhaps being unfair to the Democratic nominee by making Florida Leans Republican. Ultimately, we’re just trying to reduce the number of Toss-ups where we feel that’s warranted. Just as we think Florida going blue would probably mean a Democratic presidential victory, so too do we believe that a Republican win in Michigan probably would mean that the GOP is retaining control of the White House. So if we move either to Toss-up, it may mean that a favorite is emerging in the presidential race overall.”

Because

we’re moving Florida to Toss-up, and not really considering doing the same to Michigan, it’s fair to say that presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden is emerging as a favorite in the presidential race. Not necessarily an overwhelming favorite, but a favorite nonetheless.

Looking at the state of play in the two crucial states of Michigan and Florida help illustrate why.

Biden has

led recent Michigan polling — not always by a lot, although sometimes by double digits. Rep. Justin Amash (I, MI-3) decided not to run for president as a Libertarian, preventing him from playing spoiler as an anti-Trump candidate in his competitive home state. And while primary results cannot be used as a proxy for the fall, Biden beat Bernie Sanders in Michigan by a healthy margin in the March 10 primary (when Sanders was still an active candidate), carrying every county after Hillary Clinton had struggled against Sanders in outstate areas four years prior, indicating that, perhaps, Biden was a better candidate for non-metro Michigan — and other similar kinds of places across the competitive industrial north — than Clinton had been.

Meanwhile, in Florida, Biden actually has not

trailed a poll since mid-March. Biden has shown some surprising strength with senior citizens in many national polls, leading in some surveys with these voters after the 2016 exit polls showed Trump winning the oldest age cohort by seven. If true, this trend naturally would help Biden disproportionately in Florida, a magnet for retirees. Trump may have also jeopardized a small asset in recent days by suggesting in an

interview with

Axios that he is open to meeting with dictatorial Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and has soured on Juan Guaidó, an opposition leader that the United States has recognized as the true leader of the country. Democrats have sometimes struggled in South Florida with a perception that they are soft on despotic Latin American leaders, like the Castros and Maduro. To the extent that these developments matter to voters in South Florida, Trump may have opened himself up to criticism: There are more than 400,000 Hispanics of Venezuelan origin in South Florida, according to a recent

Politico report on Trump’s shifting stances on Venezuela’s leadership (Trump

reaffirmed opposition to Maduro in a tweet on Monday).

To be clear, we remain skeptical of the Democrats’ ability to win Florida. Republicans run circles around Democrats in organizing. Even the executive director of the Florida Democratic Party recently

told the

Washington Post, “In Florida we have a history of fumbling at the two-yard line.” No kidding. To be fair, he then said, “I don’t think we’re going to do that this year,” citing improvements to the Democrats’ organizational efforts and a growing Democratic edge in

voters registering to vote by mail. We shall see.

We have one other change this week:

We’re moving Pennsylvania from Toss-up to Leans Democratic.

The dynamic in the Keystone State is somewhat similar to that of the Wolverine State: Trump was able to squeak by in each state in large part because of great performances in outstate areas.

Clinton did perfectly well enough in metro Philadelphia and Pittsburgh to win, but she got clobbered so badly outside the big urban areas that she narrowly lost the state to Trump.

The recent changes in Pennsylvania illustrate the larger trends that animate the industrial north — places like Michigan and elsewhere. Trump is hemorrhaging votes among white voters who have a four-year college degree, and who are heavily represented in suburban counties around big cities. That’s why Clinton ran ahead of Obama in much of suburban Philadelphia. However, Trump added votes among white voters who do not hold a four-year degree, who are disproportionately represented in more rural/small city areas. A caveat that we’ll make now that we have made before: possessing or not possessing a four-year degree doesn’t say anything about someone’s intelligence, nor does it necessarily say anything definitive about a person’s income (one can be doing well economically without a degree, or be doing poorly with one). But whether one holds a four-year degree has become a highly salient distinction among white voters.

Based on a 2017 analysis of the 2016 presidential voting by Rob Griffin, John Halpin, and Ruy Teixeira for the liberal Center for American Progress — an

analysis we consider superior to the more commonly-cited national exit poll — Trump won white voters without a four-year degree by 31 points, while Clinton won white voters with a four-year degree by seven.

Something that should be concerning to the president is that recent national polling has shown him falling further behind with college whites, not matching his 2016 share with non-college whites, or both.

Quinnipiac University, in a

poll released last week showing Biden up eight nationally, had Biden up 22 points with college whites, while Trump was up 26 with non-college whites; Fox News, also released last week,

showed Biden up five with college whites, but Trump only up 16 with non-college whites; NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist College,

released a few weeks ago, had Biden up 20 with college whites and Trump up 25 with non-college whites; and

New York Times/Siena College,

released Wednesday, had Biden up 28 with college whites and Trump up 19 with non-college whites.

Margins of error for these polling subgroups are higher than the polls overall, and there are differences among the findings, but the overall takeaway, to us, is that Trump is losing ground among white voters in aggregate, when he probably needs to be gaining with at least one of the two different groups (non-college versus college).

We can see this dynamic at play in the most recent, high-quality

polls of six key swing states, including Pennsylvania, released by the

New York Times/Siena College this morning. Biden was up by 10 points in Pennsylvania, and leading in the others (Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin) by margins ranging from six to 11 points. Across the six states, Biden was leading white college voters by 21 while he was down 16 with white non-college voters, significant improvements from what polling showed in these states in fall 2016, the

New York Times‘ Nate Cohn reported.

Even in non-presidential races across the country, including Pennsylvania, there have been considerable electoral shifts along educational lines. In his 2018 reelection, Gov. Tom Wolf (D-PA) lost ground in much of Appalachian Pennsylvania, but he more than made it up by improving in the metro areas throughout the state. Despite expanding his margin by seven percentage points from 2014, the only county he picked up was Cumberland. Situated across the Susquehanna River from the capital, Harrisburg, it houses the U.S. Army War College — according to the U. S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, an above-average number of Cumberland County’s residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher. By contrast, eight counties, scattered throughout the state, supported Wolf in 2014 but not 2018 — most of these counties, such as Cambria and Carbon, have historically strong ties with the declining coal mining industry and had a once-robust union presence, which buoyed Democratic margins. In all eight counties, a lower-than-average number of residents hold four-year degrees.

Map 2 shows the differences between Wolf’s 10-point victory in 2014 compared to his 17-point win in 2018. Note the dark blue improvement for Wolf in places like Greater Pittsburgh (southwest Pennsylvania), south-central Pennsylvania (Harrisburg/York), and southeast Pennsylvania (Greater Philadelphia).

Map 2: Gov. Tom Wolf (D-PA) results, 2014 vs. 2018

You can see some signals of these Democratic regional trends through other sources. A couple of recent Democratic internal polls of PA-1, a suburban swing House seat covering Bucks County in the Philadelphia suburbs held by Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R, PA-1) that Clinton won by two points, have shown Biden up double-digits. Partisan polls, particularly those that are released publicly, usually paint a rosy picture for the side that releases them. However, we’ve seen and heard about enough polling in similar kinds of places across the nation that these surveys may not be that far from the mark. Democrats also appear to have room to grow in the Harrisburg/York area, where another Democratic internal poll of Rep. Scott Perry’s (R, PA-10) district had Biden up one point after Trump won by nine points four years ago. PA-17, a suburban Pittsburgh district won by Rep. Conor Lamb (D) in 2018, is also a prime candidate to switch from Trump to Biden: Trump carried it by just three points in 2016.

At this point, we think there’s enough room for Biden to gain in suburban/exurban Pennsylvania to offset Trump’s big leads in outstate Pennsylvania, and not much reason to think — at this point — that Trump’s level of support outside the big metro areas will be significantly better than 2016. That’s enough for us to push Pennsylvania toward Biden for now.