Dude Google is free, but try Google Scholar for empirical articles. Pew and Brooking Institute are also great sources. They publish reports on Black progress in several areas every fukking year. Don't break your brain trying to read big words though, I know you guys don't like to really read. But here are

some highlights:

- In 1964, just one in four blacks above age 25 had graduated from high school. Today, the number is 85 percent. The percentage of blacks with a college degree has risen from 4 percent to more than 21 percent

- In 1963, Black Americans had a stunningly high poverty rate of 51 percent, compared to 15 percent for white Americans. By 2021, poverty rates had declined, with white poverty at 8 percent and Black poverty at 20 percent.

- The rate of Black high school attainment has sharply increased over the past 60 years, from 24.8 percent in 1962 to 90.1 percent in 2022.

- Since the 1991 peak, the teen birth rate for Black adolescents has decreased by 67%. This is a more dramatic decrease than the overall teen birth rate, which fell 57% during the same time period.

- Unemployment has been historically low for African Americans over the last few years. Between 1974 and 1994, Black unemployment consistently remained in the double digits, with rates twice as high as those for white Americans. From 1994 to 2017, Black unemployment rates varied between 7 percent and 10 percent, occasionally spiking to nearly 17 percent during recessions. However, since 2018, Black unemployment has reached record lows of 5 percent and 6 percent, except during the 18-month recession caused by COVID-19.

@Pazzy watch how easily it is to debunk this dudes talking points.

I’m working on my own post now but let me breakdown your uninformed points really quick

I said black people are “worse off economically today than during segregation.” You said it’s not true and these are your points:

In 1964, just one in four blacks above age 25 had graduated from high school. Today, the number is 85 percent. The percentage of blacks with a college degree has risen from 4 percent to more than 21 percent

1.

You didn’t make any connection to how more education translates to economic progress. Black people are more educated but we also go into more debt to obtain that education. We have lower credit scores and higher student loan debt payments as well. Which in turn reduces our take home pay. Black women who are the most educated also reported that 51% have unmanageable student loan debt. Black college graduates are also paid less than their white counterparts.

In 1963, Black Americans had a stunningly high poverty rate of 51 percent, compared to 15 percent for white Americans. By 2021, poverty rates had declined, with white poverty at 8 percent and Black poverty at 20 percent.

Poverty rates declined for all races. This isn’t an example of black economic progress. In fact, using your own data white people had a

greater decline in poverty after integration than blacks:

White poverty rate before: 15%

White poverty rate after: 8%

Percent decline in white poverty:

53%

Black poverty rate before: 51%

Black poverty rate after: 20%

Percent decline in black poverty:

39%

That’s a 14% greater decline in poverty for the community that already has 10 times the wealth of black Americans.

The rate of Black high school attainment has sharply increased over the past 60 years, from 24.8 percent in 1962 to 90.1 percent in 2022.

Again, how does this translate into economic improvement of the black community. You’re just copying and pasting “black facts” but you lack the ability to interpret the data and translate it into the context of your argument.

Since the 1991 peak, the teen birth rate for Black adolescents has decreased by 67%. This is a more dramatic decrease than the overall teen birth rate, which fell 57% during the same time period.

Again, another black fact with no economic implications. What does birth rates have to do with economic progress?

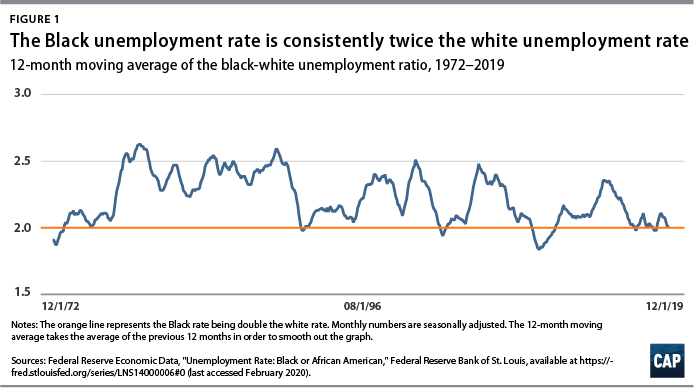

Unemployment has been historically low for African Americans over the last few years. Between 1974 and 1994, Black unemployment consistently remained in the double digits, with rates twice as high as those for white Americans. From 1994 to 2017, Black unemployment rates varied between 7 percent and 10 percent, occasionally spiking to nearly 17 percent during recessions. However, since 2018, Black unemployment has reached record lows of 5 percent and 6 percent, except during the 18-month recession caused by COVID-19.

You just admitted black unemployment rates haven’t budged for the last 50 years post integration but we made “progress?”

Employment rates doesn’t mean black people are making process. A fast food worker is employed. You could have posted statistical facts about more black doctors, scientists, etc but you clearly don’t even know what you’re arguing at this point as I have pointed out several time. Black unemployment is still double that of white unemployed and has been the same day since after segregation.

The United States needs policies that challenge structural racism in order to close the persistent unemployment gap between African Americans and whites.

www.americanprogress.org

Due to restrictions within the U.S. labor market, African Americans have long been excluded from opportunities for upward mobility, stuck instead in low-wage occupations that do not offer the protections of labor laws, such as those focused on collective bargaining, overtime, and the minimum wage.1 Unsurprisingly, this history of structural racism has created gaps in labor market outcomes between African Americans and whites.

Between strides in civil rights legislation, desegregation of government, and increases in educational attainment, employment gaps should have narrowed by now, if not completely closed.2Yet as Figure 1 shows, this has not been the case.

However, focusing on unemployment rates as a measure of economic progress has its pitfalls. For instance, the unemployment rate does not measure the strength of the labor market; strength is better illustrated through the share of workers employed in the population, or the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP). This issue brief’s analysis shows that the racial gap in EPOP is narrowing, which means that the labor market is tightening and, therefore, that the racial gap in unemployment should narrow as well, since there will be a larger pool of African American workers available for existing job openings. Yet given that the racial gap in unemployment has not narrowed—but rather persists—an alternative framework is needed to explain why.

I’m not going to post the whole article but they complete decimate your “unemployment” argument. It’s a great read.