DON’T ASK IF WE WANT TO “SELL OUR HOME.”

DON’T ASK IF OUR NEIGHBOR WANTS TO “SELL THEIR HOME.”

NO WE DON’T KNOW WHO DOES … SO DON’T ASK.

Not everyone spurns the approach, however. When I asked Jerry Joseph how he met McLaurin, he replied, “Through God, man. Through God.” McLaurin told me he looks for people in dire straits by sending out mass mailings to addresses that appear on lists of bank liens and by working a network of “guys in the neighborhood,” offering finder’s fees of $500 or $1,000. Joseph was in a typical bind: With penalties and late fees, his family now owed much more than the mortgage’s original $263,000 balance.

Standing in the backyard of the house on Arlington Avenue, Joseph said that his mother, who had inherited the property, felt helpless and was just going to let foreclosure take its course. “That’s what I’m trying to avoid,” McLaurin said. “Because there’s no compensation when the bank steps in.” He said his investors wanted to arrange a short sale, a transaction in which the bank agrees to allow a property to be sold for less than its mortgage balance. The investors would also offer Joseph’s family money up front: maybe $50,000 to his mother for the deed and $5,000 to him for vacating. “It’s called cash for keys,” McLaurin said. Joseph sounded unsure. His $5,000 wouldn’t go far in the rental market.

When Joseph was out of earshot, smoking on the front stoop, McLaurin said he figured his investors could acquire the house for a total of $200,000. “All they do is flip and rehab,” he said. In this case, the home’s second floor could be enlarged to create a rental duplex. With the J train just a block away, McLaurin estimated each unit could fetch $2,000 a month for the investors. “For them,” he said, “it’s a steal at $200,000.”

Who are all these investors? In Bushwick and Bed-Stuy, there are a few high-profile players, like Dixon Advisory, an Australian retirement fund that has recently been buying up dozens of properties—many of them former SROs—for conversion to high-end rentals. But most investors are locally based and stealthy. Several told me off the record that firms like Dixon are latecomers. “There are not any deals in Bed-Stuy,” said one. “I think suckers are buying at $1.2 million thinking they will get $2 million.”

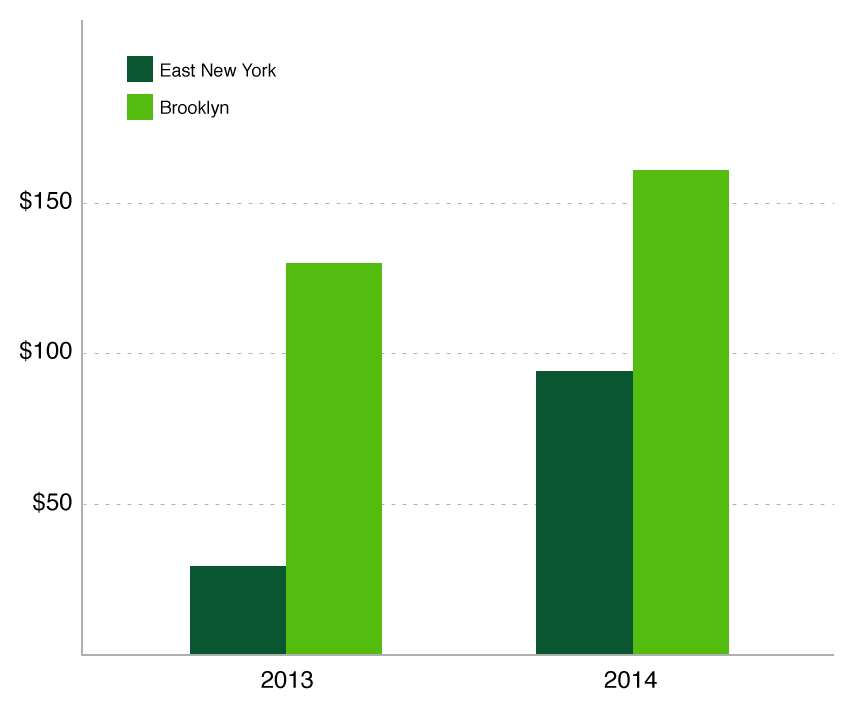

Housing Flips By Neighborhood

House flipping--a speculative phenomenon more commonly associated with Florida or Las Vegas--has recently become commonplace in the inflating market of eastern Brooklyn. The appraiser and housing market analyst Jonathan Miller counts nearly 700 flips in the area over the last two years, with prices more than doubling on average. The gentrifiying neighborhoods of Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant showed the most intense activity, but East New York wasn't far behind.

While most successful speculators tend to shun attention, I happened to know someone who could explain the game. Craig Stuart Lanza is a friend, a former Brooklyn prosecutor who now represents several investors in distressed properties. They belong to a cohort of businessmen—many of them Hasidic—who have ridden the wave east from Williamsburg. “They’ve become incredibly wealthy,” Lanza says, but they face a supply problem. “They’re running out of slums.”

Brooklyn’s speculators have developed sophisticated systems for securing inventory. The door-knockers and the short-sale brokers concentrate on finding sellers. They feed houses to deed investors, who front the cash necessary to get a property into contract. The contract itself can be flipped before closing. Often it ends up with another speculator who specializes in renovating. (Because of this off-the-books activity, the margin on a $200,000 property that flips for $1 million may be smaller than it appears.) In the background, there are hard-money lenders who finance the kind of risky deals banks won’t touch, charging high interest rates. The hard-money lender may actually be hoping for a default so that he ends up owning the property himself.

It’s a secretive business, but Lanza said he could introduce me to someone in the thick of it. We met up one day at the Brooklyn courthouse, where he first had to attend to a foreclosure auction. “This is going to be a hoot!” Lanza said. He looks like Paul Giamatti and was wearing a long camel-hair coat. The courtroom was crammed with bidders of all ethnicities. Bearded speculators murmuring in Arabic sat by bearded speculators murmuring in Yiddish. Two chatting strangers near me discovered they were both from China. Lanza sat to one side, conferring with a client, a Hasidic man in a black fur hat who specializes in buying distressed mortgages from hedge funds at a discount and foreclosing. He had a property up for auction: a four-story brick tenement on Ralph Avenue, across the street from the Brevoort Houses in Bed-Stuy. After frenzied bidding, the building sold for $1.2 million.

Then Lanza and I walked over to Atlantic Avenue to meet a client who was willing to talk: an investor named Isaac who has been flipping houses for more than a decade. As we hopped into the back of his white BMW, Lanza related the results of the auction and Isaac gave a disbelieving whistle.

“221 Ralph?” he said. “So much money!”

With his business partner, Isaac has bought and renovated about 80 properties, mostly in Bushwick and Bed-Stuy. “I will not buy in that area anymore,” he told me over dinner at a falafel joint. “I am looking outside to buy.” One area where he is investing is East New York. “If you ask me whether East New York is going to be Bed-Stuy, with the coffee shops and cool people, it’s going to be a long time,” Isaac said. But the area is getting incrementally more affluent as the working class supplants the extremely poor.

“Where are those people going to live?” Isaac wondered. “But I cannot be the welfare guy.” He figures he can bide his time, collecting rent, and profit as the city evolves. “If you want to make money,” he says, “you make money when everyone else is asleep.”

Price Per Buildable Square Foot

In 2013, development sites in East New York cost just a quarter of the going price in Brooklyn overall. But since De Blasio announced his redevelopment plan, landowners have increased their prices dramatically. (Data courtesy of Massey Knakal Realty Services.)

Others have awakened to the possibilities. “Everybody always buys land in front of a proposed rezoning,” says Alicia Glen, the deputy mayor who is overseeing the housing plan. A former Goldman Sachs executive, she coolly sized up the economics, saying the development incentives would come with stringent conditions. “Nobody in New York City has bought land in front of a proposed zoning that requires you to build affordable housing. So all these geniuses out there, who knows? I suspect that some of them are going to wind up having overpaid for their land—and by the way, that’s not my problem.”

In the next breath, though, Glen said, “I’m not here to be punitive. We want these guys to build.” Cheap land is the precondition that is supposed to make East New York’s affordable redevelopment possible. As costs rise, developers will have to maintain their profit margins by demanding either higher rents or larger city subsidies. But spending more on each project will make it harder for de Blasio to get to that big round number he has promised: 200,000 units. Thus, the city has an incentive to target households that can contribute decent rent. A million households make below $42,000 a year, and 575,000 of them lack affordable housing, according to city estimates. Yet they stand to receive only 40,000 units, fewer than will go to households earning between $67,000 and $138,000.

“There is always going to be a tension between production and other extremely important goals,” Glen conceded. “It’s just math.”

People in East New York can also add up the numbers, and that explains why some local activists are now organizing to fight City Hall. “I think people have a right to be skeptical,” says Michelle Neugebauer, executive director of the Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation. She led a December meeting for a group called the Coalition for Community Advancement, whose members are vowing to oppose the rezoning plan if it doesn’t require the new developments to be priced for local incomes. Pastor Preston Harrington, a jovial community leader, closed the meeting with a prayer. “God, where you have joined us together,” he said, “let no man—no city planner—put us asunder.”

When we met soon afterward, Glen couldn’t quite seem to fathom the opposition. “They don’t want their children or neighbors to be displaced,” she said. “But I don’t think people think it’s terrible to have cops and teachers moving into their neighborhood.” The city’s plan for East New York includes more than new buildings: transit improvements, pedestrian-friendly streets, better shopping, and, most important, programs that will fund renovations in privately owned buildings in return for rent controls. Glen’s aim is to channel Brooklyn’s wave for public benefit. “We can’t be naïve and think we can stop development in its tracks,” she said. “We see what’s coming around the corner.”

Of course, so do the profiteers. One afternoon, Neugebauer’s colleague at the Cypress Hill LDC Lisa Maldonado showed me a site the city’s rezoning study singled out as primed for redevelopment: Arlington Village, a woebegone barrackslike complex on Atlantic Avenue originally built for returning World War II veterans. “The owner has been holding out forever,” she said. We also looked at several houses that recently flipped in the half-million-dollar range, ending up at a vinyl-sided home on Autumn Avenue, purchased for $160,000 in 2013 by an LLC, renovated, and sold to a family for $610,000 last June.

“The secret is out,” Maldonado had said when we returned to her office, where we were joined by Neugebauer.

“Please don’t put that in the article!” Neugebauer interjected. “We don’t want to sell this as the place the hipsters should come to.”

Percentage of Income for Median Home by County

The firm RealtyTrac's affordability index measures the media home price in an area against its median household income. The index surpassed 50 percent in only 19 markets, mainly in New York and California. In Brooklyn, the affordability index stands at 98 percent--meaning a typical household would have to spend nearly all its monthly income to pay the mortgage on a typical home. That makes it America's least affordable home market.

It’s a disorienting political dynamic. After years of praying for housing, prosperity, and attention, local leaders are now resisting the idea of a revival imposed from above. But their wariness becomes more understandable once you realize that the bars, bikes, and bohemians are really lagging indicators of a more brutal market phenomenon. As the rich push the middle class out of brownstone Brooklyn, the middle class has been left with an unenviable choice: leave or compete with the truly poor.

The speculators may have to wait to buy Jerry Joseph’s house, though. I asked Craig Lanza to look at his foreclosure case. He called me back, bellowing, “That mortgage cannot be foreclosed!” He surmised that somewhere along the line, as the loan was sold from one bank to another, someone made a paperwork mistake. This happens frequently. Sometimes a mortgage can even be completely wiped off the books because a six-year statute of limitations has expired. “The system is fukked,” Lanza said.

Joseph’s foreclosure case has been discontinued for the time being, though he sounded surprised to hear it. His mortgage servicer certainly isn’t letting on when it sends threatening collection notices. McLaurin still hopes to arrange a short sale, since the foreclosure could be revived. For now, though, one poor household is still living, shivering, in an extremely affordable house on Arlington Avenue.

*This article appears in the January 26, 2015 issue of New York

Magazine.

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2015/01/east-new-york-gentrification.html

and dont address the people who have lived there for years and have no desire to join their organization. What was even more interesting is the fact that these same people who come and go from their apartment buildings would be quick to join a 'Co-op Board' or a 'Tenants Association' if you know... the area was all whi... I mean right

and dont address the people who have lived there for years and have no desire to join their organization. What was even more interesting is the fact that these same people who come and go from their apartment buildings would be quick to join a 'Co-op Board' or a 'Tenants Association' if you know... the area was all whi... I mean right