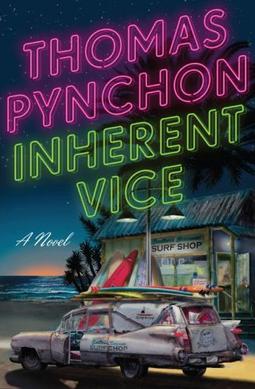

Even in the moment of watching it, Inherent Vice, feels like a half-remembered dream. The dazzling new film from Paul Thomas Anderson, a mostly faithful adaptation of a recent Thomas Pynchon novel, plays out in the dying days of free love, at the precise moment the free-nothing mindset of the Nixon era is taking root.

Anderson’s seventh picture, a strung-out comic thriller, drowning in anxious laughs, pays homage to the classic Los Angeles private-eye yarns of the early Seventies: Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, Arthur Penn’s Night Moves, and most of all Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye.

Those mighty films were made when the shadow of film noir last lingered on the Hollywood landscape, but each one acknowledged that the time for noir was over. Their throwback heroes were perched on history’s knife-edge, working out which way to jump, while the films themselves smirked from a distance.

Anderson’s man, Larry ‘Doc’ Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix), finds himself in the same predicament. With his bushy sideburns and wide straw hat, he looks like a medicated scarecrow, but anyone familiar with The Long Goodbye will recognise in him Elliott Gould’s bedraggled and muttering take on Philip Marlowe, perhaps the most enduring noir hero of them all.

Like Gould’s Marlowe – and, for that matter, Gene Hackman’s Harry Moseby in Night Moves – Phoenix’s Doc is a private investigator adrift in a mystery he can barely comprehend, let alone hope to solve. An old girlfriend, Shasta (Katherine Waterston), stops by his pad in the sleepy enclave of Gordita Beach: she suspects her lover’s wife is plotting to have him sectioned and make off with his fortune, and she asks Doc to uncover whatever plot might be in train. But then Shasta and her lover both go missing, and the trail leads Doc to the Golden Fang, a schooner docked at San Pedro that’s smuggling something or other into the U.S. from the Caribbean.

Except, hang on a second: could the Golden Fang actually be the name of an international drugs syndicate? Or is it a shadowy cabal of property developers, or dentists? Or could it be all four, or more? And why is the hippie-loathing, flat-topped LA cop ‘Bigfoot’ Bjornsen (Josh Brolin) sniffing around? As Doc investigates further, the ground beneath his feet turns to paranoid mush, and the bales of marijuana he smokes can’t be held entirely responsible.

The result is a shaggy dog story so thick and matted, you hardly know what to believe from one scene to the next – although the entire film seems to exist in a glowing, heightened place, somewhere far out beyond belief. Anderson has ditched the brooding composure of There Will Be Blood and The Master for close-up camera angles and hot, grainy colours that breathe Doc’s befuddlement straight into your lungs and brain.

Early on, Doc is knocked out cold during a bizarre visit to a sleazy massage parlour, and as he comes round, the film cuts from a gently tinkling beaded curtain to a line of red bunting flapping noisily against a hot blue sky. Doc’s headspace is ours too, and the sudden burst of colour makes him and us wince in tandem.

Anderson has named the gag-a-minute Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker comedies, such as Airplane! and The Naked Gun, as models for Inherent Vice’s comic rhythm, but while the jokes tumble past at a similar rate – a drug-fuelled car chase sequence involving Martin Short’s unhinged dentist is yelp-out-loud funny – the result isn’t entertainment so much as blissed-out bamboozlement.

Often, the comedy hangs back, too cool to insist on itself. When Brolin’s character eats a chocolate-covered banana in a manner you might describe as affectionate, Phoenix cranes his neck back in stiff disbelief, and it’s this human detail, not the accidental phallic gesture, that makes the moment hilarious.

Many of the better-known cast members, like Reese Witherspoon, Owen Wilson and Benicio Del Toro, fade in and out of the plot unexpectedly, while large chunks of Pynchon narration, delivered by Joanna Newsom’s hippie-dippie flower child Sortilège, thicken the haze of confusion to a fug.

“For weeks she could get by on just a pout,” Sortilège says of Shasta in that opening scene in Doc’s apartment. “Now she was laying some heavy combination of face ingredients on Doc that he couldn’t read at all.”

And that, in a hard nutshell, is the experience of watching Inherent Vice – or of watching it for the first time, at least. Underneath the crackpot humour, there’s something else at work; a deep-seated ache of nostalgia for a time when films were allowed to look, sound and move like this, that will surely come into sharper focus on a second viewing, when you aren’t so preoccupied with wolfing down the spaghetti tangle of the plot.

What’s clear from a bleary initial encounter, though, is that the film is stupendous: as antic as Boogie Nightsand Punch-Drunk Love, but withThe Master and There Will Be Blood’s uncanny feel for the swell and ebb of history.

“Eggs break, chocolate melts, glass shatters,” Del Toro’s character, a laconic lawyer, shrugs at one point, as he explains the meaning of the legal term that gave the film (and book) its title. In other words: everything, even the times in which we live, finally falls apart because of, not in spite of, what it’s made of. Anderson’s films may turn out to be the indestructible exceptions.

Sounds wonderful

. You need dramatic intensity, skillful storytelling, rhythm, and so forth.

. You need dramatic intensity, skillful storytelling, rhythm, and so forth.

at the potential of PTA being the greatest after boogie/magnolia then have been like

at the potential of PTA being the greatest after boogie/magnolia then have been like  since? I mean master is his best work this millennium but its not seeing his late 90s work at all. Maybe his style works better with ensembles I just hope inherent vice is a return to old

since? I mean master is his best work this millennium but its not seeing his late 90s work at all. Maybe his style works better with ensembles I just hope inherent vice is a return to old

how the fuk does someone get Japanese mixed up with spanish

how the fuk does someone get Japanese mixed up with spanish

why use you ears when you have 2 eyes eh?

why use you ears when you have 2 eyes eh?