You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

America's Most Powerful Black Families

- Thread starter invalid

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?get these nets

Veteran

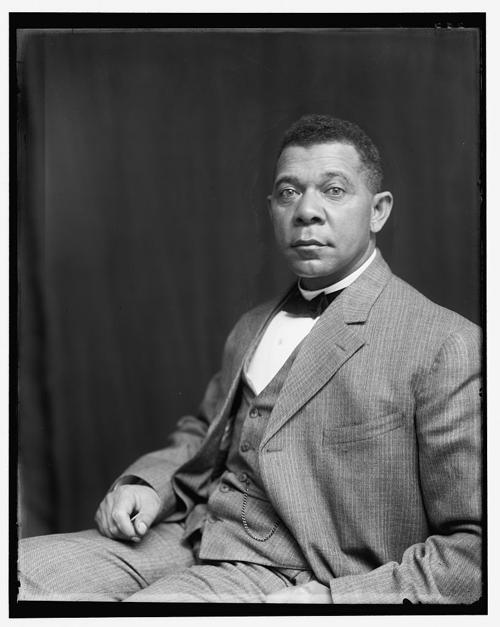

Booker T. Washington papers joining UVA's digital publication program

- Jan 18, 2021

CHARLOTTESVILLE — Booker T. Washington died 105 years ago, but his ideas, thoughts and memories are virtually alive in 14 volumes at the University of Virginia, thanks to a digital offshoot of the University Press.

Rotunda, the press’ digital label, will publish Washington’s papers under an agreement with the University of Illinois Press, which published the printed version during a 19-year span beginning in 1970.

The papers, which span from 1860 to Washington’s death in 1915, will be searchable and can be used in conjunction with other Rotunda publications in its American History Collection to provide greater context, including the papers of Ulysses S. Grant and Woodrow Wilson.

Washington’s papers will be accessible through universities, libraries and other organizations via subscription.

“If you’re in Senegal, San Francisco or Scottsville, you could have access through a library for these papers,” said Suzanne Morse Moomaw, director of the University Press. “This brings the original words of the author to a global audience. ... It’s a primary resource written by [Washington] over time.”

Moomaw said the digital collection is for use in research and, just as important, as a teaching tool. University Press and Rotunda will be working on curriculum guides for the papers during the summer.

Washington was born to an enslaved woman in 1856 in Hale’s Ford, near Roanoke, and was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. He and his mother moved to West Virginia to live with his stepfather. There, he taught himself to read and write, worked in the mines and saved enough money to go school at Hampton Institute, now known as Hampton University.

At the age of 25, he was appointed head of what would become the Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University, in Alabama. Under Washington’s lead, the school grew into a major educational center for African Americans.

As the school rose, so did Washington, becoming a player in American politics both in the Black community and white community for his belief in empowering Blacks in the face of increasing social and political sanctions in the post-Civil War South.

The papers include complete correspondence and several published books, as well as documentary material from his time at Hampton Institute and Tuskegee, said David Sewell, manager of digital initiatives for the Rotunda imprint.

The papers also feature correspondence with other Black scholars and leaders of his time, including civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, who co-founded the NAACP.

Washington’s 1895 Atlanta Exposition speech called for African American investment in industrial education and accumulating wealth as the way to integrate society at large. His position eschewed direct confrontation with whites, even as white-led legislatures passed discriminatory laws.

Washington’s views were criticized by many contemporary Black activists, including Du Bois. Critics believed Washington’s ideas were too slow, too conservative and too accepting of discrimination and segregation.

But Washington’s efforts at education and economic expansion for the African American community won him praise from two presidents. In 1898, President William McKinley declared Washington to be “one of the great leaders of his race.” President Theodore Roosevelt invited Washington to dine at the White House, an event that outraged many white political leaders and won Roosevelt support among Black leaders.

“We’re not the first to put the [Washington] papers online, but our version can be used in conjunction with other papers from the time period to provide a more inclusive look at history through different people,” Sewell said.

“It tells a different story of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and allows us to tell a fuller American story from many different sources,” Moomaw said. “I think it’s a major step forward to make it available. We’re very proud of it.”

get these nets

Veteran

Unlike the Coli, for many, there seems to be no question with respect to Kamala's loyalty to the black community because she has embraced many of the "accoutrements" of "blackness" deemed as "important" among the black establishment.

In addition to choosing to attend Howard University,

she chose to pledge Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority.

That would be enough for many of these folks.

But she was also inducted into the Links, Inc.

And if anyone knows anything about the Links, they would not have inducted her if her blackness and service to the black community was not the top most priority.

So I also think her induction sealed the deal for many people.

When are the most powerful Black families going to lobby and make big moves?

From Vernon Jordan to his wife Ann Dibble Cook Jordan to her cousin Valerie Bowman Jarrett, the family in the OP has been in the halls of power (the White House) for the past 40 years. What bigger moves can you get?

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Binga Dismond's wife - Geraldyn Hodges Dismond Major aka Gerri Major authored Black Society

Black Society was the original Our Kind of People.

It has really great history of the black elites and include pedigrees and very detailed info on, for instance, the family of Absalom Jones - the Abeles and their connection to what was called the "Washingtonian Triumvirate" - the Cook - Wormley - Syphax families.

If you don't have it try to get it.

Difference between Black Society and OKOP is that Black Society spotlighted the Old Antebellum Black Aristocracy whereas OKOP spotlighted the newer elites post-Great Depression/Great Migrations.

All of these folks are my grandmother's father's people.

Her maternal side were Free People of Color from Ohio.

[/SPOILER]

I can really go more into detail but I've given enough information where if you dig a little further you could find out who I am and I would like to stay anonymous on this board, at least, because I wild out.......sometimes-lol.

I didn't realize that the Syphaxs were connected to one of the founders of Sigma Pi Phi

.

.

John McKee (1821 – 6 April 1902)

.

.

funny story on one of his descendants

@IllmaticDelta Bro, we on the same time.

I literally started a post this morning that was going to lead up to John McKee and cover all of them. I was backing up from the Davis Family who are Wormleys. Edith Wormley Minton was the wife of Henry McKee Minton, the founder of the Boule. Her niece is Mavis Wormley Davis who is the aunt of Lizzie Cooper Davis.

I’ve been wanting to back up to Col. John McKee for a reason. He is the closest thing to the evil “house slave” archetype that I have seen from the black elite. That man was a trip.

But yeah, the Wormley, Syphax, Cook clans are the “Washingtonian Triumvirate” that I’m going to touch on in my post. All married each other. The Wormleys connect to the Chicago Davis family and the Cooks connect to the Chicago Dibbles - Ann Dibble Cook Jordan was first married to Mercer Cook of DC before she married Vernon Jordan.

Edit: Also Henry Mckee Minton was cousins with one of the other Boule founders Robert Abele, who was from the Abele-Cook clan that connects to Absalom Jones. All them folks did was intermarry.

I literally started a post this morning that was going to lead up to John McKee and cover all of them. I was backing up from the Davis Family who are Wormleys. Edith Wormley Minton was the wife of Henry McKee Minton, the founder of the Boule. Her niece is Mavis Wormley Davis who is the aunt of Lizzie Cooper Davis.

I’ve been wanting to back up to Col. John McKee for a reason. He is the closest thing to the evil “house slave” archetype that I have seen from the black elite. That man was a trip.

But yeah, the Wormley, Syphax, Cook clans are the “Washingtonian Triumvirate” that I’m going to touch on in my post. All married each other. The Wormleys connect to the Chicago Davis family and the Cooks connect to the Chicago Dibbles - Ann Dibble Cook Jordan was first married to Mercer Cook of DC before she married Vernon Jordan.

Edit: Also Henry Mckee Minton was cousins with one of the other Boule founders Robert Abele, who was from the Abele-Cook clan that connects to Absalom Jones. All them folks did was intermarry.

Last edited:

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

@IllmaticDelta Bro, we on the same time.

I literally started a post this morning that was going to lead up to John McKee and cover all of them. I was backing up from the Davis Family who are Wormleys. Edith Wormley Minton was the wife of Henry McKee Minton, the founder of the Boule. Her niece is Mavis Wormley Davis who is the aunt of Lizzie Cooper Davis.

I’ve been wanting to back up to Col. John McKee for a reason. He is the closest thing to the evil “house slave” archetype that I have seen from the black elite. That man was a trip.

But yeah, the Wormley, Syphax, Cook clans are the “Washingtonian Triumvirate” that I’m going to touch on in my post. All married each other. The Wormleys connect to the Chicago Davis family and the Cooks connect to the Chicago Dibbles - Ann Dibble Cook Jordan was first married to Mercer Cook of DC before she married Vernon Jordan.

Edit: Also Henry Mckee Minton was cousins with one of the other Boule founders Robert Abele, who was from the Abele-Cook clan that connects to Absalom Jones. All them folks did was intermarry.

make that post

@IllmaticDelta Read about John McKee’s descendant years ago that was passing for white, then came out as negro so he could claim that inheritance.

Too good to be negro until it was time to claim negro money.

I believe he also was a Phillips Exeter Academy classmate of Roscoe Conkling Bruce, the son of the first black Senator Blanche K. Bruce. Roscoe would be one of the early invitees to join Sigma Pi Phi.

Too good to be negro until it was time to claim negro money.

I believe he also was a Phillips Exeter Academy classmate of Roscoe Conkling Bruce, the son of the first black Senator Blanche K. Bruce. Roscoe would be one of the early invitees to join Sigma Pi Phi.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

@IllmaticDelta Read about John McKee’s descendant years ago that was passing for white, then came out as negro so he could claim that inheritance.

Too good to be negro until it was time to claim negro money.

I believe he also was a Phillips Exeter Academy classmate of Roscoe Conkling Bruce, the son of the first black Senator Blanche K. Bruce. Roscoe would be one of the early invitees to join Sigma Pi Phi.

yup, I think I read that he told Roscoe he was going to "crossover" to the other side

Called INBRRED BOULE SOCIETThey all have a certain look about them....I can't quite put my finger on what it is....

Opulence decadence tuxes next to the president ,

From Vernon Jordan to his wife Ann Dibble Cook Jordan to her cousin Valerie Bowman Jarrett, the family in the OP has been in the halls of power (the White House) for the past 40 years. What bigger moves can you get?

We have seen gentrification at places that could have been saved with Black investments, where the Black dollar could have been circulated. Now that’s bigger. Of course that faces challenges that can be overcome.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

...somewhat related to my last post but kinda off topic

Her Japanese grandparents got reparations; her African American ancestors did not. Was that fair?

The Washington Post

Her Japanese grandparents got reparations; her African American ancestors did not. Was that fair?

Her father’s ancestors were enslaved at Mount Vernon. Unlike the vast majority of enslaved African Americans, the Syphaxes became landowners, though it took an act of Congress to gain full recognition of their property rights.

The impacts of government-sanctioned racism course through both branches of Robyn Syphax’s family tree. That uncommon lineage shows how even token compensation for historical wrongs can reverberate through generations, affording a chance to heal.

Japanese Americans received reparations — a presidential apology and a $20,000 check — more than four decades after their captivity. African Americans have not.

The Washington Post

Last edited:

...somewhat related to my last post but kinda off topic

Her Japanese grandparents got reparations; her African American ancestors did not. Was that fair?

The Washington Post

Interesting.

What are your thoughts? And maybe you can explain to me why #ADOS are in a tizzy in the comments?

I keep seeing them say that the author is undermining the ADOS fight for reparations.

But it seems like the article is doing the exact opposite?

The Syphaxes certainly did leverage the land given to them by George Washington Parke Custis. It was only 17 acres though. 17 valuable acres that they leveraged, and certainly made them wealthy, but not enough recompense in my opinion.

As an aside, I'm a descendant of Samuel Washington, George Washington's brother.

Actually, that line connects to my Ontario -> Detroit, Hughes/Binga/Morris clans.

We have seen gentrification at places that could have been saved with Black investments, where the Black dollar could have been circulated. Now that’s bigger. Of course that faces challenges that can be overcome.

I've asked this question a lot on here and don't really get sufficient answers.

What would you like to see the black elite do to help the black community?

I Really Mean It

Veteran

Powerful black family.