IV. Early Season 6, Part 2: Tony’s Paternal Rage Intensifies

Soprano Home Movies

The first 5 episodes of season 6, part 2, establish a parabolic crescendo of subplots dealing with violent fathers and sons – real and surrogate -- and the repression of guilt, hatred, and rage between them.

Soprano Home Movies starts things off when Tony asks Bobby if he ever “popped his cherry” (killed anyone). “Nah,” Bobby replies. This puzzles Tony since Bobby got made anyway and had a notorious mob hitman for a father. “I come close. I done other shyt, but no. . . .

My pop never wanted it for me.” (emphasis added) Bobby goes on to observe that modern DNA and other evidence make legal complications for murder much more problematic than in years past.

Tony salutes him for having avoided the act. “It’s a big, fat pain in the balls.” His tone of voice and introspective expression betray that his statement has little to do with the legal complications of murder and everything to do with the psychological complications.

His choice of words also suggests an important association in Tony’s subconscious: murder is a pain literally in the source of his masculinity, a pain resulting from his effort to fulfill his father’s expectations and ideas of manhood. (If this association isn’t clear from

Soprano Home Movies alone, it becomes abundantly clear in

Remember When two episodes later.)

As is typical in the Sopranos, and in life, events rarely have one cause. The monopoly fight in this episode is a good example. Contributory causes included inebriation and a dispute over the free parking rule. But the biggest impetus came when Janice told the story of Johnny Boy shooting a hole through Livia’s hairdo, despite Tony’s vociferous objection. Tony’s vindictiveness immediately kicked in, and things went precipitously downhill afterward.

Similar to the finger chopping incident, the hair story was so shameful to Tony that he never even told Carmela, a fact that shocks her because of the ostensible hilarity of a bullet hole in the middle of a beehive bun. While everyone else laughs, he seems ashamed not only because the act is blatantly violent but because the victim was a spouse, not some loanshark debtor. He growls at Janice, “It makes us look like a fukkin’ dysfunctional family,” then warns Carmela, “Don’t you ever tell the kids that about their grandfather.” He still protects Johnny to the core because his maternal blame/paternal hero worship is his defense mechanism to personal responsibility and regret for his lifestyle.

However losing the fight to Bobby on the heels of the discussion about murder stirred a cauldron of unconscious hatred in Tony towards the father whose example and imparted value system factored indirectly into both the fight and Tony’s severe humiliation at defeat as well as into his envy for a peer whose father loved him enough to shield him from the ultimate crime. I could rarely ever predict what was about to happen on The Sopranos, but as soon as I saw Tony brooding with his black eye and swollen jaw by that lake, I felt he would be shortly ordering Bobby to perform his first hit. It was perfect, hideous retribution for someone who has often sought to sabotage another’s personal growth, stability, happiness, or moral superiority, especially when he’s feeling the narrow limits of his own.

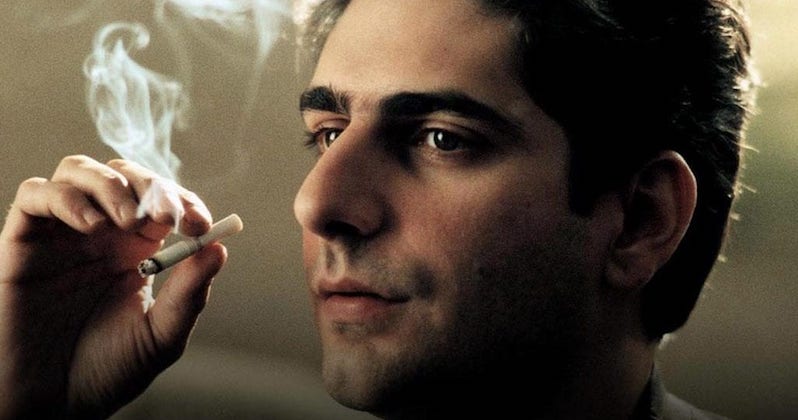

When Bobby returns home to the strains of “This Magic Moment” after committing his first murder, the subtext is clear. He has lost forever what modicum of innocence he could claim as a made guy. He will never be the same again, his psyche irrevocably scarred in a way that Tony understands all too well since, as we soon learn, he committed his first murder at age 22 . . . on orders of his own father.

There are a few other notable scenes in

Soprano Home Movies. The first occurs by the lake when Tony urges Carmela to share the story of the three year-old that was left with severe brain damage after nearly drowning in a swimming pool amid a party full of adults. Tony doesn’t know why but proclaims, “I can’t get that story out of my mind.”

In a scene after the fight, he hones in on the nanny singing the nursery song “Five Little Ducks” with toddler Domenica. The first stanza of that song goes:

Five little ducks

Went out one day

Over the hill and far away

Mother duck said

"Quack, quack, quack, quack."

But only four little ducks came back.

The remaining stanzas build in a pattern on this one, each time with one fewer ducks going out and one fewer returning. The excerpt in the episode is edited so that it abruptly cuts off after the nanny and child sing “Mother duck”, leaving those words most prominent.

These two anecdotes speak in concert to the issue of parental (and especially maternal) neglect, of a mother not properly protecting or keeping account of her children in view of the risks around them. They are especially apposite as Sopranos subtext because Tony’s subconscious, and the show as a whole, have used ducks and pools as symbols for Tony’s own family and sense of homelife throughout. Moreover Tony’s admitted fixation on the toddler drowning story reinforces the vicarious insight Melfi was trying to get Tony to absorb two episodes earlier, that part of his unrelenting grudge against Livia owes to her failure to protect him from his father.

The whole theme is poignantly symbolized near the episode’s close as Tony watches the old 8mm film transfers of him and Janice, around ages 4-6, respectively. They were “two little ducks” playing with a hose on the sidewalk, an inflatable pool nearby. They are strikingly alone in the film. There is no sign of Livia, or any other adult in front of the camera, only the prominence of their father’s black, 1959 Cadillac, symbolically equivalent, as we know, to the gangster lifestyle of Johnny Soprano.

The upshot of these “Soprano home movies” is that the children were left prey to the dangers of a gangster father by a self-absorbed, unloving mother. Yet that’s a source of anger he can’t possibly confront and safely discharge because he still can’t confront the bigger truth that his father was the kind of man from whom he needed protection.