cole phelps

Superstar

Press coverage

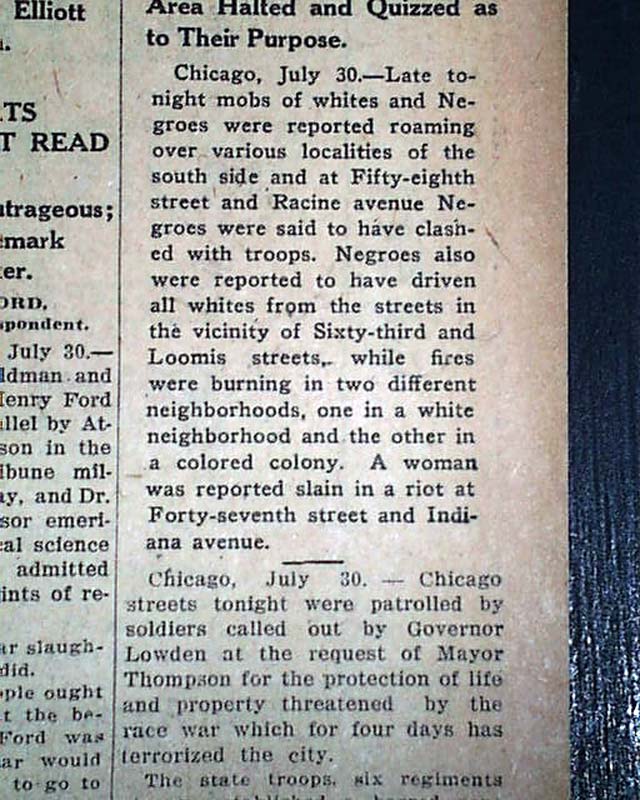

In mid-summer, in the middle of the Chicago riots, a federal official told the New York Times that the violence resulted from "an agitation, which involves the I.W.W., Bolshevism and the worst features of other extreme radical movements."[28] He supported that claim with copies of negro publications that called for alliances with leftist groups, praised the Soviet regime, and contrasted the courage of jailed Socialist Eugene V. Debs with the "school boy rhetoric" of traditional black leaders. The Times characterized the publications as "vicious and apparently well financed," mentioned "certain factions of the radical Socialist elements," and reported it all under the headline: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt."[28]

In response, some black leaders such as Bishop Charles Henry Phillips of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church asked blacks to shun violence in favor of "patience" and "moral suasion." Phillips opposed propaganda favoring violence, and he noted the grounds of injustice to the blacks:

"I cannot believe that the negro was influenced by Bolshevist agents in the part he took in the rioting. It is not like him to be a traitor or a revolutionist who would destroy the Government. But then the reign of mob law to which he has so long lived in terror and the injustices to which he has had to submit have made him sensitive and impatient."[29]

The connection between blacks and bolshevism was widely repeated. In August 1919, the Wall Street Journal wrote: "Race riots seem to have for their genesis a Bolshevist, a Negro, and a gun." The National Security League repeated that reading of events.[30] In presenting the Haynes report in early October, The New York Times provided a context which his report did not mention. Haynes documented violence and inaction on the state level.

The Times saw "bloodshed on a scale amounting to local insurrection" as evidence of "a new negro problem" because of "influences that are now working to drive a wedge of bitterness and hatred between the two races."[1] Until recently, the Times said, black leaders showed "a sense of appreciation" for what whites had suffered on their behalf in fighting a civil war that "bestowed on the black man opportunities far in advance of those he had in any other part of the white man's world."[1] Now militants were supplanting Booker T. Washington, who had "steadily argued conciliatory methods." The Times continued:[1]

Every week the militant leaders gain more headway. They may be divided into general classes. One consists of radicals and revolutionaries. They are spreading Bolshevist propaganda. It is reported that they are winning many recruits among the colored race. When the ignorance that exists among negroes in many sections of the country is taken into consideration the danger of inflaming them by revolutionary doctrine may [be] apprehended.... The other class of militant leaders confine their agitation to a fight against all forms of color discrimination. They are for a program on uncompromising protest, 'to fight and continue to fight for citizenship rights and full democratic privileges.'

As evidence of militancy and Bolshevism, the Times named W.E.B. Du Bois and quoted his editorial in The Crisis, which he edited: "Today we raise the terrible weapon of self-defense....When the armed lynchers gather, we too must gather armed." When the Times endorsed Haynes' call for a bi-racial conference to establish "some plan to guarantee greater protection, justice, and opportunity to negroes that will gain the support of law-abiding citizens of both races," it endorsed discussion with "those negro leaders who are opposed to militant methods."[1]

In mid-October government sources provided the Times with evidence of Bolshevist propaganda appealing to America's black communities. This account set Red propaganda in the black community into a broader context, since it was "paralleling the agitation that is being carried on in industrial centres of the North and West, where there are many alien laborers."[31] The Times described newspapers, magazines, and "so-called 'negro betterment' organizations" as the way propaganda about the "doctrines of Lenin and Trotzky" was distributed to blacks.[31] It cited quotes from such publications, which contrasted the recent violence in Chicago and Washington, D.C. with

In mid-summer, in the middle of the Chicago riots, a federal official told the New York Times that the violence resulted from "an agitation, which involves the I.W.W., Bolshevism and the worst features of other extreme radical movements."[28] He supported that claim with copies of negro publications that called for alliances with leftist groups, praised the Soviet regime, and contrasted the courage of jailed Socialist Eugene V. Debs with the "school boy rhetoric" of traditional black leaders. The Times characterized the publications as "vicious and apparently well financed," mentioned "certain factions of the radical Socialist elements," and reported it all under the headline: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt."[28]

In response, some black leaders such as Bishop Charles Henry Phillips of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church asked blacks to shun violence in favor of "patience" and "moral suasion." Phillips opposed propaganda favoring violence, and he noted the grounds of injustice to the blacks:

"I cannot believe that the negro was influenced by Bolshevist agents in the part he took in the rioting. It is not like him to be a traitor or a revolutionist who would destroy the Government. But then the reign of mob law to which he has so long lived in terror and the injustices to which he has had to submit have made him sensitive and impatient."[29]

The connection between blacks and bolshevism was widely repeated. In August 1919, the Wall Street Journal wrote: "Race riots seem to have for their genesis a Bolshevist, a Negro, and a gun." The National Security League repeated that reading of events.[30] In presenting the Haynes report in early October, The New York Times provided a context which his report did not mention. Haynes documented violence and inaction on the state level.

The Times saw "bloodshed on a scale amounting to local insurrection" as evidence of "a new negro problem" because of "influences that are now working to drive a wedge of bitterness and hatred between the two races."[1] Until recently, the Times said, black leaders showed "a sense of appreciation" for what whites had suffered on their behalf in fighting a civil war that "bestowed on the black man opportunities far in advance of those he had in any other part of the white man's world."[1] Now militants were supplanting Booker T. Washington, who had "steadily argued conciliatory methods." The Times continued:[1]

Every week the militant leaders gain more headway. They may be divided into general classes. One consists of radicals and revolutionaries. They are spreading Bolshevist propaganda. It is reported that they are winning many recruits among the colored race. When the ignorance that exists among negroes in many sections of the country is taken into consideration the danger of inflaming them by revolutionary doctrine may [be] apprehended.... The other class of militant leaders confine their agitation to a fight against all forms of color discrimination. They are for a program on uncompromising protest, 'to fight and continue to fight for citizenship rights and full democratic privileges.'

As evidence of militancy and Bolshevism, the Times named W.E.B. Du Bois and quoted his editorial in The Crisis, which he edited: "Today we raise the terrible weapon of self-defense....When the armed lynchers gather, we too must gather armed." When the Times endorsed Haynes' call for a bi-racial conference to establish "some plan to guarantee greater protection, justice, and opportunity to negroes that will gain the support of law-abiding citizens of both races," it endorsed discussion with "those negro leaders who are opposed to militant methods."[1]

In mid-October government sources provided the Times with evidence of Bolshevist propaganda appealing to America's black communities. This account set Red propaganda in the black community into a broader context, since it was "paralleling the agitation that is being carried on in industrial centres of the North and West, where there are many alien laborers."[31] The Times described newspapers, magazines, and "so-called 'negro betterment' organizations" as the way propaganda about the "doctrines of Lenin and Trotzky" was distributed to blacks.[31] It cited quotes from such publications, which contrasted the recent violence in Chicago and Washington, D.C. with

"Soviet Russia, a country in which dozens of racial and lingual types have settled their many differences and found a common meeting ground, a country which no longer oppresses colonies, a country from which the lynch rope is banished and in which racial tolerance and peace now exist."[31]

The Times noted a call for unionization: "Negroes must form cotton workers' unions. Southern white capitalists know that the negroes can bring the white bourbon South to its knees. So go to it."[31]

Coverage of the root causes of the riot in Elaine, Arkansas evolved as the violence stretched over several days. A dispatch from Helena, Arkansas to the New York Times datelined October 1 said: "Returning members of the [white] posse brought numerous stories and rumors, through all of which ran the belief that the rioting was due to propaganda distributed among the negroes by white men."[32] The next day's report added detail: "Additional evidence has been obtained of the activities of propagandists among the negroes, and it is thought that a plot existed for a general uprising against the whites." A white man had been arrested and was "alleged to have been preaching social equality among the negroes." Part of the headline was: "Trouble Traced to Socialist Agitators."[33] A few days later a Western Newspaper Union dispatch captioned a photo using the words "Captive Negro Insurrectionists."[34]

The Times noted a call for unionization: "Negroes must form cotton workers' unions. Southern white capitalists know that the negroes can bring the white bourbon South to its knees. So go to it."[31]

Coverage of the root causes of the riot in Elaine, Arkansas evolved as the violence stretched over several days. A dispatch from Helena, Arkansas to the New York Times datelined October 1 said: "Returning members of the [white] posse brought numerous stories and rumors, through all of which ran the belief that the rioting was due to propaganda distributed among the negroes by white men."[32] The next day's report added detail: "Additional evidence has been obtained of the activities of propagandists among the negroes, and it is thought that a plot existed for a general uprising against the whites." A white man had been arrested and was "alleged to have been preaching social equality among the negroes." Part of the headline was: "Trouble Traced to Socialist Agitators."[33] A few days later a Western Newspaper Union dispatch captioned a photo using the words "Captive Negro Insurrectionists."[34]

i feel you

i feel you