The

Elaine Race Riot, also called the

Elaine Massacre, occurred September 30, 1919 in the town of

Elaine in

Phillips County, Arkansas, in the

Arkansas Delta, where

sharecropping by

African American farmers was prevalent on

plantations of white landowners. Approximately 100

African-American farmers, led by

Robert L. Hill, the founder of the

Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America, met at a church in

Hoop Spur in

Phillips County, nearby Elaine. The purpose was "to obtain better payments for their cotton crops from the

white plantation owners who dominated the area during the

Jim Crow era. Black

sharecroppers were often exploited in their efforts to collect payment for their cotton crops."

[1]

Background

About 100 black

sharecroppers had gathered at the Hoop Spur Church in Elaine, Arkansas, before dawn on October 1, 1919. They wanted to be able to obtain better prices for their products from the white planters who controlled the land. They considered joining the

Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. They also were discussing filing a

class action lawsuit against their landlords. Union members advocating for the union brought armed guards to protect the meeting.

O.A. Rogers, Jr. was President of the

Arkansas Baptist College in

Little Rock. In the summer 1960 issue of the

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, he wrote:

“Sharecropping The African Americans had been having trouble in getting settlements for the

cotton they raised on land owned by whites. Both the Negroes and the white owners were to share the profits when the crop was sold for the year. Between the time of planting and selling, the sharecroppers took up food, clothing, and necessities at excessive prices from the plantation store owned by the planter.”

It was not a practice of the landowners and the sharecroppers to go together to a market to dispose of the cotton when it was ready. Rather, the landowner sold the crop whenever and however he saw fit. At the time of settlement, neither an itemized statement of accounts owed nor an accounting of the money received for cotton and seed, was, in most cases, given or shown the Negroes. It was an unwritten law of the cotton country that they could not quit and leave a plantation until their debts were paid. Many Negroes in Phillips County whose cotton was sold in October, 1918, did not get a settlement before July of the following year.

According to the Historical Text Archive on

Revolution in the Land: Southern Agriculture in the 20th Century in a section called

[2] "The Changing Face of Sharecropping and Tenancy":

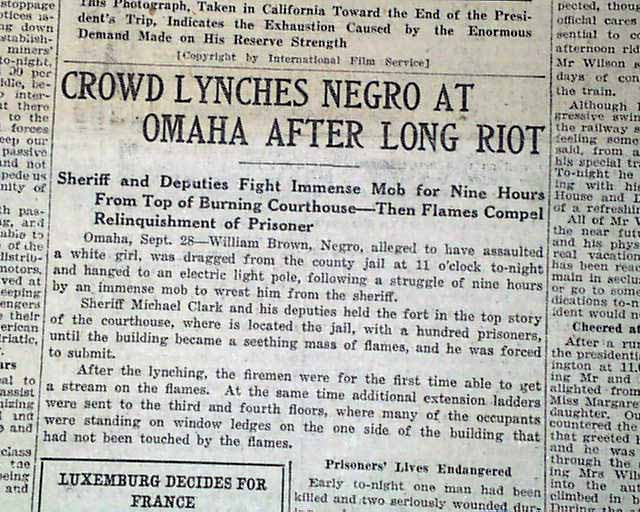

“Late in the evening of September 30, 1919, black sharecroppers were holding a union meeting in a church in Hoop Spur outside of Elaine, Arkansas. Tensions were high and they had posted guards at the door. When two deputized white men and a black trustee pulled into view, shots rang out. Who fired first is still debated, likely unknowable, and perhaps not that important. What is important is what transpired afterwards. One of the white men was killed, the other wounded. The black trustee raced back to Helena, the county seat of Phillips County, and alerted officials. A posse was dispatched and within a few hours hundreds of white men, many of them the "low down" variety, began to comb the area for blacks they believed were launching an insurrection. In the end, five white men and over a hundred African Americans were killed. Some estimates of the black death toll range in the hundreds. Allegations surfaced that the white posse and even U.S. soldiers who were brought in to put down the so called "rebellion" had massacred defenseless black men, women and children. Nearly a hundred blacks were arrested, and in sham trials that lasted no more than a few minutes each, sixty-something black men were sentenced to prison, and twelve were slated for execution. A massive effort on the part of the NAACP and others, including a prominent black attorney in Little Rock, ensued, and by 1925 all the men were free. But planters had established that blacks had best not organize, even within the law, for racism would bring whites of different classes together to put them down.”

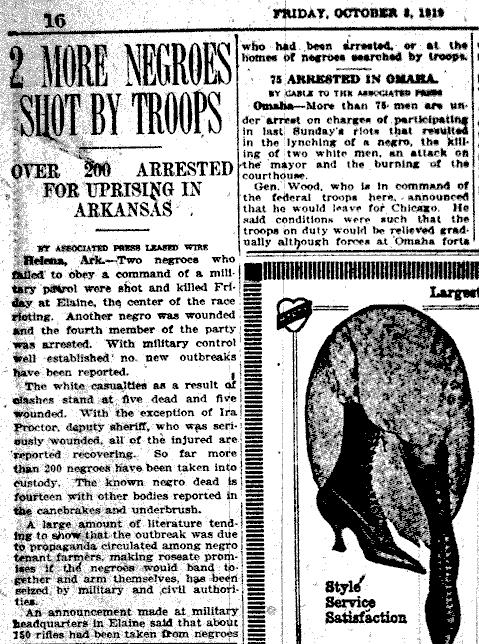

Many more blacks than whites died as a result of the violence. Five whites and between 100 and 200 blacks were killed.

[3][4]

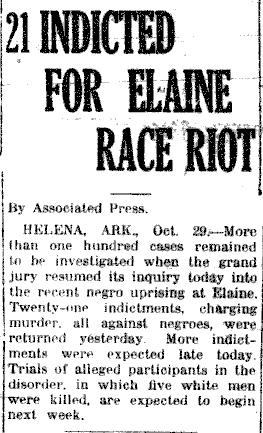

Seventy-nine African Americans were charged with crimes and tried and convicted, with 12 sentenced to death, and the remainder accepting terms of up to 21 years. Appeals of the death penalty cases went to the

U.S. Supreme Court where the high court ruled in favor of an expansion of federal oversight of state treatment of defendants' rights.

[3]

The summer of 1919 had been marked by

deadly race riots in numerous major cities across the country, including

Chicago,

Knoxville, and

Washington, DC. In addition, postwar tensions were high because of labor unrest across the country. Added to labor tensions were racial ones — in

Phillips County, a plantation area of the

Mississippi Delta since before the Civil War, blacks outnumbered whites by ten to one. Whites feared resistance to their domination. They also wanted blacks out of the country or dead.

Events

When a white deputy sheriff and a

railroad detective, arrived at the church, a fight broke out between them and the guards. In the ensuing gunfire, the railroad detective was killed and the deputy sheriff was wounded.

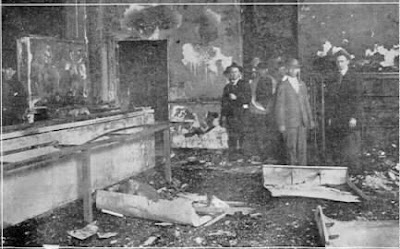

The parish sheriff called for a posse to investigate and capture those who were responsible for the killing. Violence expanded beyond the meeting place. Additional armed white men came into the county from outside to support the white citizens until a mob of 500 to 1,000 armed men had formed. Fighting in the area lasted for three days. Sensational newspaper articles reported that an "insurrection" was occurring. After arriving in Elaine, white men roamed the area randomly attacking and killing black men.

Area whites also requested help from Arkansas Governor

Charles Hillman Brough, citing a "Negro uprising". As the mob was gathering, Brough contacted the

War Department and requested Federal troops. After considerable delay, approximately 500 U.S. troops arrived and found the area in chaos. The troops made their way to the area of the Hoop Spur Church, where they exchanged gunfire with black farmers in the woods. Over the next few days, the troops disarmed both parties and arrested 285 black residents, putting them in stockades for investigation and protection.

Several African American and white citizens were killed and more wounded. At least two and possibly more were killed by Federal troops. The exact number of blacks killed is unknown because of the wide area of attacks, but estimates ranged from 100 to 200.

[3][4]