Clear and Present Danger (Oscar De La Hoya’s 1999 welterweight clash with Ike Quartey)

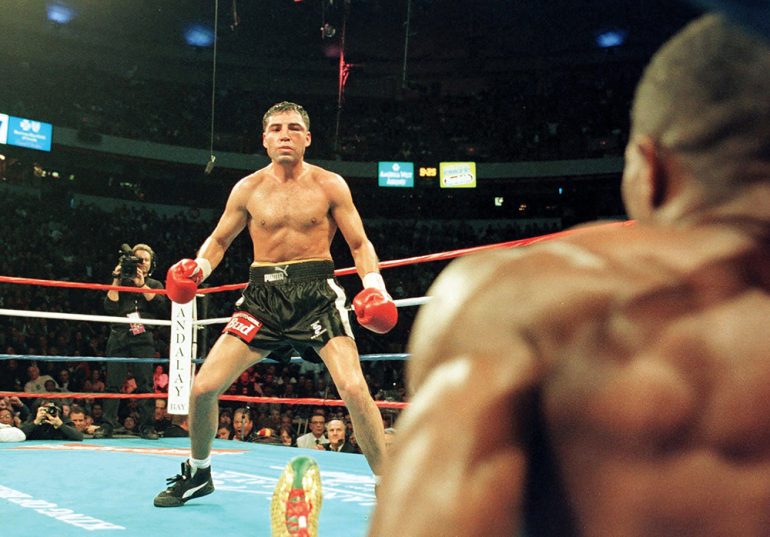

De La Hoya came back strong in the championship rounds vs. then-unbeaten Quartey. Photo by JOHN GURZINSKI/AFP via Getty Images

04

Feb

IKE QUARTEY REPRESENTED THE FIRST REAL PHYSICAL THREAT TO DE LA HOYA’S WELTERWEIGHT TITLE REIGN, AND THE FORMIDABLE GHANAIAN LIVED UP TO IT IN ONE OF THE GOLDEN BOY’S HARDEST-FOUGHT VICTORIES

Oscar De La Hoya understood what the presence of Ike “Bazooka” Quartey across the ring from him meant. It meant, for perhaps the first time in his career, danger was lurking only the length of a long jab away. De La Hoya insisted before the first bell sounded on February 13, 1999, at the Thomas and Mack Center in Las Vegas that he welcomed its arrival.

Sponsored Content

Recommended by

In a gambler’s town where most visitors come away losers, the undefeated Golden Boy of boxing was pushing all his chips into the center of that ring. Golden or tarnished? That was the risk Quartey posed that night.

At the time, the 26-year-old De La Hoya was 29-0 with 24 knockouts, but more importantly he was an Olympic gold medalist, a winner of five world titles in four weight classes and 17 straight title fights and the biggest non-heavyweight drawing card in the sport. He had already taken belts from the likes of Genaro Hernandez, Julio Cesar Chavez, Pernell Whitaker and Miguel Angel Gonzalez, all formidable champions although considered flawed in one way or another, either by a lack of size or the ravages of age. Quartey, the undefeated former WBA welterweight titleholder, had none of those issues dogging him.

Nine months shy of 30, Quartey was a fighter with a piston-like jab, concussion-producing power, a 34-0-1 record that included 29 knockouts and a healthy disrespect for golden boys like De La Hoya. There was only one word to describe what he was at that moment.

“If you can see danger in front of you and feel this guy can beat you, you do everything it takes to win,” De La Hoya said before the fight. “This is a dangerous fight, but I wanted it. I needed this. I was losing my focus. I need dangerous fights now to stay motivated. Sometimes getting ready for [these types of fighters] is easier than getting ready for Joe Schmoe.”

Perhaps so, but the problem with “those types of” fighters is they don’t fight like Joe Schmoe. They come to the arena with supreme confidence and bad intentions, and no one felt the latter more than Isufu “Ike” Quartey, a native of Ghana who had learned to fight in the accepted way. He fought to keep what little he had.

That was long before he wore $250 sunglasses, as he did during fight week. It was when he was a street kid from Bukom, a tough neighborhood in the bowels of Accra, Ghana’s capital city. It was there that Ike Quartey first learned the value of being dangerous.

The youngest of the 27 children of Robert Quartey, a court bailiff with five wives and a hard-earned reputation as a street fighter, Ike grew up hungry, literally and figuratively. As a kid, he once fought savagely to retain ownership of a scuffed soccer ball, one of his few possessions. The kid who tried to take it from him was Alfred Kotey, himself a future world champion whom Quartey would follow into a steamy boxing gym to begin walking their dual roads to fame and fortune. But long before he got to his $3 million moment with De La Hoya, there was the matter of ownership of that scuffed ball to settle.

“You have something someone wants, they take it,” Quartey once said of his boyhood while sitting in a Las Vegas coffee shop. “Back there, you fight in the streets every day. You fight for everything. That is life there.”

Quartey’s fighting life in the ring began when he left his father’s crowded home in Bukom as a young boy to move in with a boxing trainer. If one Googles the word “Bukom,” the second thing that comes up is “Bukom is known for its output of successful boxers to America.” Like Kotey and boxing idol Azumah Nelson, Quartey would become another fighting export of Bukom.

“I left my house at 7 or 8,” Quartey claimed. “My mother did not want me to be a boxer, so I went to live with my trainer.”

Verifying such details of the life of a boy from Ghana is difficult, but one thing was clear by the evening of February 13, 1999: Quartey had learned to fight somewhere. And by the time he faced De La Hoya, he had more than lived up to the reputation of a brother he never knew.

The original Ike Quartey won a silver medal as a light welterweight at the 1960 Olympics in Rome when he was 26, nearly nine years before the younger Ike was born. While Isufu was fighting over a soccer ball, his big brother was off making a living in Mexico. The younger Ike had no recollection of him, but he knew what he had accomplished and so took his name and followed his road through pain to fame, a road that now had led him to face the American Golden Boy whom he’d grown to hate.

There were many boxers who resented the fame and fortune young De La Hoya had amassed since turning pro only six years earlier, but Quartey had another reason for his feelings. He believed the postponement of their original fight date three months earlier had been a ploy by De La Hoya to avoid the fate that now awaited him. De La Hoya withdrew from the original fight date after suffering a cut eyelid in sparring, but the rumor was that he was not in tip-top shape and needed extra time to get ready for the legitimate threat that Quartey presented.

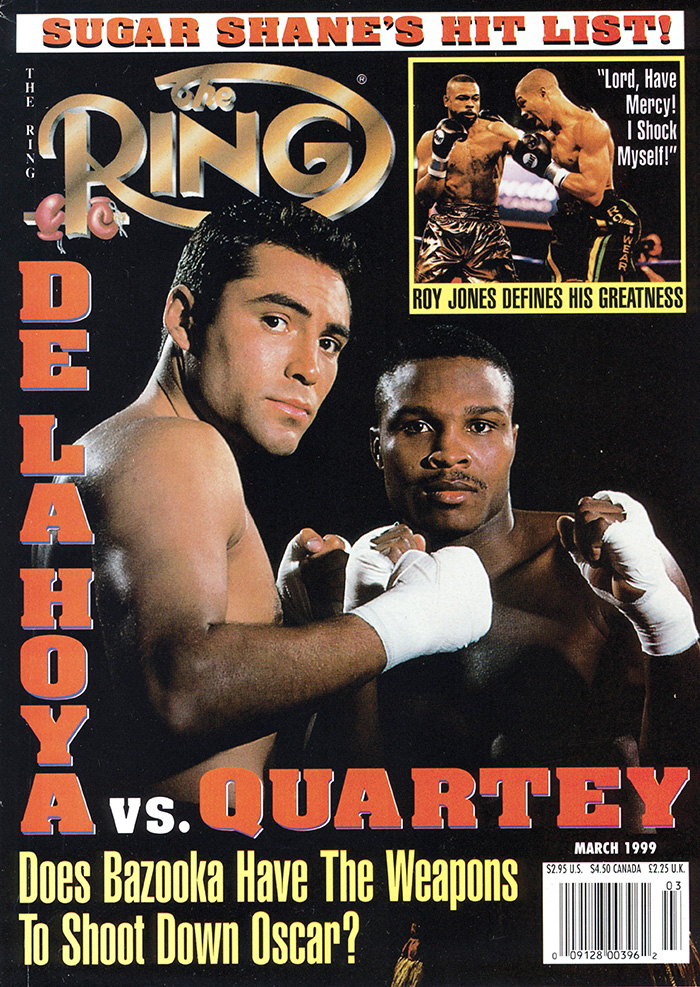

De La Hoya and Quartey finally squared off in 1999. (Photo from The Ring archive)

Quartey’s enmity was exacerbated by what had become a 14-month layoff since fighting to a disappointing draw against Jose Luis Lopez, who had dropped him twice. Quartey’s trainer claimed Quartey had refused to postpone that fight despite suffering with a virus some later claimed was a case of malaria, and he’d later been stripped of his WBA title for choosing to fight De La Hoya for the biggest payday of his career rather than a lesser WBA-sanctioned challenger.

Quartey came to believe that not only had the decision to fight De La Hoya cost him his title, but also that De La Hoya, who now held the WBC welterweight belt, had only agreed to face him after seeing he’d struggled against Lopez. For this, Quartey said, De La Hoya must pay a steep price.

“I want to hurt him because he made me mad,” Quartey said before the fight. “I am going to beat him like he was my son.”