You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Official African American Thread#2

- Thread starter Rhapscallion Démone

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Black Lightning

Superstar

Diane Nash

Civil rights activist Diane Judith Nash was born on May 15, 1938 in Chicago, Illinois to Leon Nash and Dorothy Bolton Nash. Nash grew up a Roman Catholic and attended parochial and public schools in Chicago. In 1956, she graduated from Hyde Park High School in Chicago, Illinois and began her college career at Howard University in Washington, D.C. before transferring to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.

While a student in Nashville Nash witnessed southern racial segregation for the first time in her life. In 1959, she attended nonviolent protest workshops led by Reverend James Lawsonwho was affiliated with the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference. Later that year she protested exclusionary racial policies by participating in impromptu sit-ins at Nashville’s downtown lunch counters. Nash was elected chair of the Student Central Committee because of her nonviolent protest philosophy and her reputation from these sit-ins.

By February 13, 1960, the mass sit-ins that began in Greensboro, North Carolina on February 1 had spread to Nashville. Nash organized and led many of the protests which ultimately involved hundreds of black and white area college students. As a result, by early April Nashville Mayor Ben West publicly called for the desegregation of Nashville’s lunch counters and organized negotiations between Nash and other student leaders and downtown business interests. Because of these negotiations, on May 10, 1960 Nashville, Tennessee became the first southern city to desegregate lunch counters.

Meanwhile Nash and other students from across the South assembled in Raleigh, North Carolina at the urging of NAACP activist Ella Baker. There they founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in April 1960.

After the Nashville sit-ins, Nash helped coordinate and participated in the 1961 Freedom Rides across the Deep South. Later that year Nash dropped out of college to become a full-time organizer, strategist, and instructor for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) headed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Nash married civil rights activist James Bevel in 1961 and moved to Jackson, Mississippiwhere she began organizing voter registration and school desegregation campaigns for SCLC. Arrested dozens of times for their civil rights work in Mississippi and Alabama in the early 1960s, Nash and her husband, James Bevel, received SCLC’s Rosa Parks award from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1965. Dr. King cited especially their contributions to the Selma Right-to-vote movement that eventually led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1966, Nash joined the Vietnam Peace Movement. Through the 1960s she stayed involved in political and social transformation. In the 1980s she fought for women’s rights. Nash now works in real estate in her home town Chicago, Illinois, but continues to speak out for social change.

Civil rights activist Diane Judith Nash was born on May 15, 1938 in Chicago, Illinois to Leon Nash and Dorothy Bolton Nash. Nash grew up a Roman Catholic and attended parochial and public schools in Chicago. In 1956, she graduated from Hyde Park High School in Chicago, Illinois and began her college career at Howard University in Washington, D.C. before transferring to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.

While a student in Nashville Nash witnessed southern racial segregation for the first time in her life. In 1959, she attended nonviolent protest workshops led by Reverend James Lawsonwho was affiliated with the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference. Later that year she protested exclusionary racial policies by participating in impromptu sit-ins at Nashville’s downtown lunch counters. Nash was elected chair of the Student Central Committee because of her nonviolent protest philosophy and her reputation from these sit-ins.

By February 13, 1960, the mass sit-ins that began in Greensboro, North Carolina on February 1 had spread to Nashville. Nash organized and led many of the protests which ultimately involved hundreds of black and white area college students. As a result, by early April Nashville Mayor Ben West publicly called for the desegregation of Nashville’s lunch counters and organized negotiations between Nash and other student leaders and downtown business interests. Because of these negotiations, on May 10, 1960 Nashville, Tennessee became the first southern city to desegregate lunch counters.

Meanwhile Nash and other students from across the South assembled in Raleigh, North Carolina at the urging of NAACP activist Ella Baker. There they founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in April 1960.

After the Nashville sit-ins, Nash helped coordinate and participated in the 1961 Freedom Rides across the Deep South. Later that year Nash dropped out of college to become a full-time organizer, strategist, and instructor for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) headed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Nash married civil rights activist James Bevel in 1961 and moved to Jackson, Mississippiwhere she began organizing voter registration and school desegregation campaigns for SCLC. Arrested dozens of times for their civil rights work in Mississippi and Alabama in the early 1960s, Nash and her husband, James Bevel, received SCLC’s Rosa Parks award from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1965. Dr. King cited especially their contributions to the Selma Right-to-vote movement that eventually led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1966, Nash joined the Vietnam Peace Movement. Through the 1960s she stayed involved in political and social transformation. In the 1980s she fought for women’s rights. Nash now works in real estate in her home town Chicago, Illinois, but continues to speak out for social change.

Black Lightning

Superstar

Daisy Bates

Daisy Bates was a mentor to the Little Rock Nine, the African-American students who integrated Central High School in Little Rock in 1957. She and the Little Rock Nine gained national and international recognition for their courage and persistence during the desegregation of Central High when Governor Orval Faubus ordered members of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the entry of black students. She and her husband, L. C. Bates, published the Arkansas State Press, a newspaper dealing primarily with civil rights and other issues in the black community.

Daisy Lee Gatson on November 11, 1914, in Huttig, Arkansas. Her childhood was marked by racial violence. Her mother was sexually assaulted and murdered by three white men and her father left shortly after that, forcing Daisy to be raised by friends of the family.

At the age of 15, Daisy became the object of an older man’s attention, Lucious Christopher “L. C.” Bates, an insurance salesman who had also worked on newspapers in the South and West. L.C. dated her for several years, and they married in 1942, living in Little Rock. The Bates decided to act on a dream of theirs, to run their own newspaper, leasing a printing plant that belonged to a church publication and inaugurating the Arkansas State Press. The first issue appeared on May 9, 1941. The paper became an avid voice for civil rights even before a nationally recognized movement had emerged.

In 1942, the paper reported on a local case where a black soldier, on leave from Camp Robinson, was shot by a local policeman. An advertising boycott nearly broke the paper, but a statewide circulation campaign increased the readership, and restored its financial viability. Continuing to write about civil liberties Daisy Bates was an active member of the NAACP and in 1952, she was elected president of the Arkansas State Conference of NAACP branches.

Daisy Bates became a key figure in the Little Rock Nine, one of the most important events in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. On May 17, 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court issued it's historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The decision declared all laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional, and it called for the desegregation of all schools throughout the nation. Following this landmark decision the NAACP worked to register black students in previously all-white schools in cities throughout the South.

The Little Rock School Board agreed to follow the court's ruling and approved a plan of gradual integration that would begin in the fall of 1957 at the beginning of the following school year. The NAACP went on to register nine students to attend the previously all-white Little Rock Central High. The students, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Beals, were chosen on the criteria of excellent grades and attendance.

Several segregationist councils threatened to hold protests at Central High and physically block the black students from entering the school. Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to support the segregationists on September 4, 1957, vowing "blood will run in the streets" if black students tried to enter Central High. The sight of a line of soldiers blocking nine black students from attending high school made national headlines and polarized the city. Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Arkansas Nine, recalled "They moved closer and closer. Somebody started yelling, I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the crowd, someone who maybe could help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me."

Although Wiley Branton of Jefferson County was the local attorney for the NAACP and handled much of the litigation, Dasisy Bates, in her capacity as president of the Arkansas Conference of Branches, was recognized as the principal spokesperson and leader for the forces behind the school desegregation. She had also been instrumental in selecting the nine students and had personally approached each of the families, asking them to step forward and participate. Daisy Bates was in constant contact with NAACP leaders and in constant conflict with segregationists using intimidation in Arkansas.

On September 9, "The Council of Church Women" issued a statement condemning the governor's deployment of soldiers to the high school and called for a citywide prayer service on September 12. President Dwight Eisenhower attempted to de-escalate the situation and summoned Governor Faubus to meet him. The President warned the governor not to interfere with the Supreme Court's ruling. With all the threats of violence Woodrow Mann, the Mayor of Little Rock, asked President Eisenhower to send federal troops to enforce integration and protect the nine students.

In recognition of her leadership, the national Associated Press chose her as the Woman of the Year in Education in 1957, along with being one of the top ten newsmakers in the world. Sadly, in 1959, as a result of intimidation by news distributors and a boycott by white business owners who withheld advertising, the Bates were forced to close the Arkansas State Press.

Daisy Bates published her autobiography and account of the Little Rock Nine in 1962, and continued her struggle for Civil Rights, working for the Democratic National Committee until she was forced to stop when she suffered a stroke in 1965.

In 1984, the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville awarded Daisy Bates an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Carrying the Olympic torch in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics was one of Daisy Bates last honors before she passed away in 1999.

Daisy Bates was a mentor to the Little Rock Nine, the African-American students who integrated Central High School in Little Rock in 1957. She and the Little Rock Nine gained national and international recognition for their courage and persistence during the desegregation of Central High when Governor Orval Faubus ordered members of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the entry of black students. She and her husband, L. C. Bates, published the Arkansas State Press, a newspaper dealing primarily with civil rights and other issues in the black community.

Daisy Lee Gatson on November 11, 1914, in Huttig, Arkansas. Her childhood was marked by racial violence. Her mother was sexually assaulted and murdered by three white men and her father left shortly after that, forcing Daisy to be raised by friends of the family.

At the age of 15, Daisy became the object of an older man’s attention, Lucious Christopher “L. C.” Bates, an insurance salesman who had also worked on newspapers in the South and West. L.C. dated her for several years, and they married in 1942, living in Little Rock. The Bates decided to act on a dream of theirs, to run their own newspaper, leasing a printing plant that belonged to a church publication and inaugurating the Arkansas State Press. The first issue appeared on May 9, 1941. The paper became an avid voice for civil rights even before a nationally recognized movement had emerged.

In 1942, the paper reported on a local case where a black soldier, on leave from Camp Robinson, was shot by a local policeman. An advertising boycott nearly broke the paper, but a statewide circulation campaign increased the readership, and restored its financial viability. Continuing to write about civil liberties Daisy Bates was an active member of the NAACP and in 1952, she was elected president of the Arkansas State Conference of NAACP branches.

Daisy Bates became a key figure in the Little Rock Nine, one of the most important events in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. On May 17, 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court issued it's historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The decision declared all laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional, and it called for the desegregation of all schools throughout the nation. Following this landmark decision the NAACP worked to register black students in previously all-white schools in cities throughout the South.

The Little Rock School Board agreed to follow the court's ruling and approved a plan of gradual integration that would begin in the fall of 1957 at the beginning of the following school year. The NAACP went on to register nine students to attend the previously all-white Little Rock Central High. The students, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Beals, were chosen on the criteria of excellent grades and attendance.

Several segregationist councils threatened to hold protests at Central High and physically block the black students from entering the school. Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to support the segregationists on September 4, 1957, vowing "blood will run in the streets" if black students tried to enter Central High. The sight of a line of soldiers blocking nine black students from attending high school made national headlines and polarized the city. Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Arkansas Nine, recalled "They moved closer and closer. Somebody started yelling, I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the crowd, someone who maybe could help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me."

Although Wiley Branton of Jefferson County was the local attorney for the NAACP and handled much of the litigation, Dasisy Bates, in her capacity as president of the Arkansas Conference of Branches, was recognized as the principal spokesperson and leader for the forces behind the school desegregation. She had also been instrumental in selecting the nine students and had personally approached each of the families, asking them to step forward and participate. Daisy Bates was in constant contact with NAACP leaders and in constant conflict with segregationists using intimidation in Arkansas.

On September 9, "The Council of Church Women" issued a statement condemning the governor's deployment of soldiers to the high school and called for a citywide prayer service on September 12. President Dwight Eisenhower attempted to de-escalate the situation and summoned Governor Faubus to meet him. The President warned the governor not to interfere with the Supreme Court's ruling. With all the threats of violence Woodrow Mann, the Mayor of Little Rock, asked President Eisenhower to send federal troops to enforce integration and protect the nine students.

In recognition of her leadership, the national Associated Press chose her as the Woman of the Year in Education in 1957, along with being one of the top ten newsmakers in the world. Sadly, in 1959, as a result of intimidation by news distributors and a boycott by white business owners who withheld advertising, the Bates were forced to close the Arkansas State Press.

Daisy Bates published her autobiography and account of the Little Rock Nine in 1962, and continued her struggle for Civil Rights, working for the Democratic National Committee until she was forced to stop when she suffered a stroke in 1965.

In 1984, the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville awarded Daisy Bates an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Carrying the Olympic torch in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics was one of Daisy Bates last honors before she passed away in 1999.

Black Lightning

Superstar

Audley “Queen Mother” Moore

Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, prominent Harlem civil rights activist, was born in 1898, in New Iberia, Louisiana to Ella and St. Cry Moore. Moore’s parents passed away before she completed primary school. Following their deaths, she dropped out of school to earn a living as a hairdresser to support her two younger sisters. She educated herself by reading the writings of Frederick Douglass and listening to the speeches of Marcus Garvey.

Moved by the Black Nationalist message in a speech Marcus Garvey gave in New Orleans, Moore migrated to Harlem, New York in 1922 during the early years of the Harlem Renaissance. While in Harlem, she became a member and then leader within Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). A proud shareholder in the Black Star Line, she helped organize UNIA conventions in New York. Moore married Frank Warner in 1922. They had one son, Thomas.

After the demise of the UNIA, Moore founded several organizations. With her base in Harlem, Moore founded and served as president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women in 1950. In 1963 she founded the Committee for Reparations for Descendants of U. S. Slaves, and The Republic of New Africa, which demanded self-determination, land, and reparations for African Americans. During the height of the Cold War, Moore presented a petition to the United Nations in 1957 which demanded land and billions in reparations for people of African descent and it requested direct support for African Americans who sought to immigrate to Africa.

Moore also focused on local issues. In 1966 she participated a sit-in at a Board of Education meeting in Brooklyn in 1966. Moore and the other protesters said board members failed to adequately fund schools in African-American communities. She also served as the bishop of the Apostolic Orthodox Church of Judea and she co-founded the Commission to Eliminate Racism, Council of Churches of Greater New York.

While attending the funeral of former Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah in 1972, the Ashanti ethnic group bestowed upon her honorary title “Queen Mother.” In 1989, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C. honored Moore and 40 other famous black women in Brian Lanker’s photo exhibit, “I Dream a World.”

Moore’s activism continued through the mid-1990s, where she made her final public appearance at the Million Man March in 1995. On May 2, 1997 Queen Mother Moore passed away at the age of 98 from natural causes in a Brooklyn nursing home. At the time of her death she was survived by a son, five grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, prominent Harlem civil rights activist, was born in 1898, in New Iberia, Louisiana to Ella and St. Cry Moore. Moore’s parents passed away before she completed primary school. Following their deaths, she dropped out of school to earn a living as a hairdresser to support her two younger sisters. She educated herself by reading the writings of Frederick Douglass and listening to the speeches of Marcus Garvey.

Moved by the Black Nationalist message in a speech Marcus Garvey gave in New Orleans, Moore migrated to Harlem, New York in 1922 during the early years of the Harlem Renaissance. While in Harlem, she became a member and then leader within Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). A proud shareholder in the Black Star Line, she helped organize UNIA conventions in New York. Moore married Frank Warner in 1922. They had one son, Thomas.

After the demise of the UNIA, Moore founded several organizations. With her base in Harlem, Moore founded and served as president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women in 1950. In 1963 she founded the Committee for Reparations for Descendants of U. S. Slaves, and The Republic of New Africa, which demanded self-determination, land, and reparations for African Americans. During the height of the Cold War, Moore presented a petition to the United Nations in 1957 which demanded land and billions in reparations for people of African descent and it requested direct support for African Americans who sought to immigrate to Africa.

Moore also focused on local issues. In 1966 she participated a sit-in at a Board of Education meeting in Brooklyn in 1966. Moore and the other protesters said board members failed to adequately fund schools in African-American communities. She also served as the bishop of the Apostolic Orthodox Church of Judea and she co-founded the Commission to Eliminate Racism, Council of Churches of Greater New York.

While attending the funeral of former Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah in 1972, the Ashanti ethnic group bestowed upon her honorary title “Queen Mother.” In 1989, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C. honored Moore and 40 other famous black women in Brian Lanker’s photo exhibit, “I Dream a World.”

Moore’s activism continued through the mid-1990s, where she made her final public appearance at the Million Man March in 1995. On May 2, 1997 Queen Mother Moore passed away at the age of 98 from natural causes in a Brooklyn nursing home. At the time of her death she was survived by a son, five grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Black Lightning

Superstar

This 14-year-old Georgia girl will be youngest student to attend Spelman College

STONECREST, Ga. — A 14-year-old Georgia girl will be the youngest student to attend Spelman College after excelling academically from a young age.

Sydney Wilson was solving algebraic equations in the first grade and began taking high-school level classes at The Wilson Academy when she was ten.

The Wilson Academy is a year-round private school located in Stonecrest, Georgia. The school was founded by Sydney’s father, Akron, Ohio native and Ohio State University graduate Byron F. Wilson, in 2002. The school is one of Dekalb County’s best private schools and offers a unique curriculum and innovative approach to education.

Sydney, who was a straight-A student, worked hard to get into Spelman College, which had reportedly been her top and only choice school since she was 8 years old.

While taking on college-prep and advanced placement coursework, Sydney also served as the lead programmer for her school’s robotics team, was president of the rotary club, ran track and played soccer for a nationally ranked club team.

Sydney finished top of her class as co-valedictorian and graduated with honors May 18.

Her father told WJW Sydney was actually accepted into Spelman when she was just 13 years old. She turned 14 on May 15.

In fact, the Wilson family had attended a college exposition last year where Sydney had been offered scholarships and acceptances to other colleges based on her transcripts, but she reportedly wasn’t ready to head off to college at age 13.

“[Sydney] is thrilled to be attending such a storied HBCU (Historically Black College and University), and that it is one of the top colleges in the country,” her father said.

Sydney, a member of the incoming class of 2023, plans to major in biology. She also hopes to gain “real world experience” by living in a dorm and partaking in a hands-on biology program made possible by partnership with the Morehouse School of Medicine.

The Wilson Academy is a year-round private school located in Stonecrest, Georgia. The school was founded by Sydney’s father, Akron, Ohio native and Ohio State University graduate Byron F. Wilson, in 2002. The school is one of Dekalb County’s best private schools and offers a unique curriculum and innovative approach to education.

STONECREST, Ga. — A 14-year-old Georgia girl will be the youngest student to attend Spelman College after excelling academically from a young age.

Sydney Wilson was solving algebraic equations in the first grade and began taking high-school level classes at The Wilson Academy when she was ten.

The Wilson Academy is a year-round private school located in Stonecrest, Georgia. The school was founded by Sydney’s father, Akron, Ohio native and Ohio State University graduate Byron F. Wilson, in 2002. The school is one of Dekalb County’s best private schools and offers a unique curriculum and innovative approach to education.

Sydney, who was a straight-A student, worked hard to get into Spelman College, which had reportedly been her top and only choice school since she was 8 years old.

While taking on college-prep and advanced placement coursework, Sydney also served as the lead programmer for her school’s robotics team, was president of the rotary club, ran track and played soccer for a nationally ranked club team.

Sydney finished top of her class as co-valedictorian and graduated with honors May 18.

Her father told WJW Sydney was actually accepted into Spelman when she was just 13 years old. She turned 14 on May 15.

In fact, the Wilson family had attended a college exposition last year where Sydney had been offered scholarships and acceptances to other colleges based on her transcripts, but she reportedly wasn’t ready to head off to college at age 13.

“[Sydney] is thrilled to be attending such a storied HBCU (Historically Black College and University), and that it is one of the top colleges in the country,” her father said.

Sydney, a member of the incoming class of 2023, plans to major in biology. She also hopes to gain “real world experience” by living in a dorm and partaking in a hands-on biology program made possible by partnership with the Morehouse School of Medicine.

The Wilson Academy is a year-round private school located in Stonecrest, Georgia. The school was founded by Sydney’s father, Akron, Ohio native and Ohio State University graduate Byron F. Wilson, in 2002. The school is one of Dekalb County’s best private schools and offers a unique curriculum and innovative approach to education.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Horace King (1807-1885)

was an American architect, engineer, and bridge builder.[1] King is considered the most respected bridge builder of the 19th century Deep South, constructing dozens of bridges in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.[2] "In 1807, King was born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation. A slave trader sold him to a man who saw something special in Horace King. His owner, John Godwin taught King to read and write as well as how to build at a time when it was illegal to teach slaves. King worked hard and despite bondage, racial prejudice and a multitude of obstacles, King focused his life on working hard and being a genuinely good man. King built bridges, warehouses, homes, churches, and most importantly, he bridged the depths of racism. Ultimately, dignity, respect and freedom were his rewards, as he transcended the color lines inherent in the Old South of the nineteenth century. Horace King became a highly accomplished Master Builder and he emerged from the Civil War as a legislator in the State of Alabama. Affectionately known as Horace “The Bridge Builder” King and the "Prince of Bridge Builders," he also served his community in many important civic capacities." [3].

Final years

King in his later years.

King left the Alabama Legislature in 1872 and moved with his family to LaGrange, Georgia. While in LaGrange, King continued building bridges, but also expanded to include other construction projects, specifically businesses and schools. By the mid-1870s, King had begun to pass on his bridge construction activities to his five children, who formed the King Brothers Bridge Company. King's health began failing in the 1880s, and he died on May 28, 1885 in LaGrange.[23]

King received laudatory obituaries in each of Georgia's major newspapers, a rarity for African Americans in the 1880s South. He was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Engineers Hall of Fame at the University of Alabama. The award was accepted on his behalf by his great-grandson, Horace H. King, Jr.[24] He was remembered both for his engineering skill and for his character.[25]

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Dana Albert "D. A." Dorsey (1872–1940)

Dana A. Dorsey, better known as D.A. Dorsey, was a Georgia man who arrived in Miami to work as a carpenter on Flagler’s railroad. He saw a need among fellow workers for housing, so he got into real estate. He purchased land in Overtown and redeveloped it into affordable housing.

Through years of development, reinvestment and entrepreneurship, Dorsey became Miami’s first black millionaire. He owned property in Dade and Broward counties, Cuba and the Bahamas. He later built the Dorsey Hotel, the first black-owned hotel in the city, and founded the first black bank. Dorsey even bought and sold present-day Fisher Island.

Dorsey sold land to establish Miami’s first park for blacks, and donated land for the city’s first library for blacks and the site of Dorsey High School, which is now D.A. Dorsey Technical College. Today, the D. A. Dorsey house at 250 NW 9th Street is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, and is owned by The Black Archives History and Research Foundation of South Florida. Dorsey also left a philanthropic legacy in the community.

When Dorsey died in 1940, flags were lowered to half-staff all over Miami. He was buried in Lincoln Memorial Park, Miami’s African American cemetery during segregation.

Reparations: Reasonable and Right

It is America’s responsibility to undo the trauma it has inflicted upon black people for hundreds of years.

By Charles M. Blow

Opinion Columnist

Carolyn Smith, a descendant of a slave, gestures toward gravestones of other descendants of enslaved people in Houma, La.CreditClaire Vail/American Ancestors, via New England Historic Genealogical Society, via Associated Press

Image

Carolyn Smith, a descendant of a slave, gestures toward gravestones of other descendants of enslaved people in Houma, La.CreditCreditClaire Vail/American Ancestors, via New England Historic Genealogical Society, via Associated Press

This week, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was asked his opinion on the paying of reparations to the descendants of slavery in America, and he came down solidly on the side of “no” and on the side of being intentionally obtuse.

Here is his answer in full:

“I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago, for whom none of us currently are responsible, is a good idea. We’ve tried to deal with our original sin of slavery by fighting a civil war, by passing landmark civil rights legislation. We’ve elected an African-American president. I think we’re always a work in progress in this country, but no one currently alive was responsible for that.

“And, I don’t think we should be trying to figure out how to compensate for it. First of all, it would be pretty hard to figure out who to compensate. We’ve had waves of immigrants as well who come to the country and experienced dramatic discrimination of one kind or another. So no, I don’t think reparations are a good idea.”

Everything McConnell said was fundamentally wrong — factually and morally.

Let’s start at the beginning: Chattel slavery in America is not merely “something that happened” 150 years ago. This year happens to be the 400th anniversary of when the first enslaved African arrived on our shores, and slavery became an indescribably horrific institution that thrived for nearly 250 years.

And the unpaid, unrewarded labor of those enslaved Africans is in large part what made America an economic powerhouse, and now one of the wealthiest countries in the world. And yet, the enslaved reaped none of the benefits of the wealth they created.

Does that sound fair or right?

Here it is important to point out that reparations are not only about the institution of slavery, but also about the century of oppression, a form of semi-slavery that came in its wake through racial terror, black codes and Jim Crow.

From the very beginning, emancipation wasn’t whole. During slavery, the enslaved were not counted as fully human — they were to be counted as three-fifths of a person as set forth in the Constitution — but the Supreme Court’s horrendous decision in the Dred Scott v. Sanford case confirmed that black people were not and could not become citizens of this country.

In the introduction to what remains a jaw-dropping decision, the author writes:

“The doctrine of 1776, that all (white) men ‘are created free and equal,’ is universally accepted and made the basis of all our institutions, State and National, and the relations of citizenship — the rights of the individual — in short, the status of the dominant race, is thus defined and fixed for ever.”

Black people would not be considered citizens until the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, but the 13th Amendment, ratified three years earlier, the year the Civil War ended, had already left a backdoor for quasi reimposition of slavery, stating, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

That exception was just the backdoor that many in power needed, leading to further abominations, like convict leasing. As the Equal Justice Initiativehas explained:

“After the Civil War, slavery persisted in the form of convict leasing, a system in which Southern states leased prisoners to private railways, mines and large plantations. While states profited, prisoners earned no pay and faced inhumane, dangerous and often deadly work conditions. Thousands of black people were forced into what authors have termed ‘slavery by another name’ until the 1930s.”

Does that sound fair or right?

When slavery ended, many slaves thought that they would receive 40 acres and a mule; instead, they got pestilence and starvation. In the eyes of America, all their labor had earned them nothing.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. touched on this gross failure of America in speeches just before he died and in advance of his planned Poor People’s Campaign, saying:

“At the same time that America refused to give the Negro any land, through an act of Congress, our government was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and Midwest, which meant that it was willing to undergird its white peasants from Europe with an economic floor. But not only did they give the land, they built land grant colleges, with government money, to teach them how to farm. Not only that, they provided county agents to further their expertise in farming. Not only that, they provided low interest rates in order that they could mechanize their farms. Not only that, today many of these people are receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies, not to farmand they are the very people telling the black man that he ought to lift himself by his own boot straps.”

King finished:

“Now, when we come to Washington, in this campaign, we’re coming to get our check.”

The enslaved were freed into an epidemic of sickness and death.

The historian Jim Downs estimatesthat “at least one quarter of the four million former slaves got sick or died between 1862 and 1870,” as The New York Times pointed out when his book, “Sick From Freedom,” was released in 2012.

There was no medical infrastructure — or educational or financial, for that matter — to support them. The federal government said it was the states’ responsibility, and the states shirked it, saying, in part, that they had enough to handle, with thousands of wounded soldiers returning. So, the bodies fell and the tombstones sprouted.

Does any of this sound fair or right to you?

In an 1888 speech, Frederick Douglass would blast America’s faux emancipation of black people, saying:

“I admit that the Negro, and especially the plantation Negro, the tiller of the soil, has made little progress from barbarism to civilization, and that he is in a deplorable condition since his emancipation. That he is worse off, in many respects, than when he was a slave, I am compelled to admit, but I contend that the fault is not his, but that of his heartless accusers. He is the victim of a cunningly devised swindle, one which paralyzes his energies, suppresses his ambition, and blasts all his hopes; and though he is nominally free he is actually a slave. I here and now denounce his so-called emancipation as a stupendous fraud — a fraud upon him, a fraud upon the world.”

During Reconstruction, not only was the Freedmen’s Bureau established, so was the Freedman’s Bank, in part because white banks wouldn’t do business with black people. After the bank had been run into the ground by mismanagement, Douglass was brought in as president to save it. But it was too late. Just three months later the bank was allowed to fail.

As the National Archives put it:

“The closure of Freedman’s Bank devastated the African-American community. An idea that began as a well-meaning experiment in philanthropy had turned into an economic nightmare for tens of thousands of African Americans who had entrusted their hard-earned money to the bank. Contrary to what many of its depositors were led to believe, the bank’s assets were not protected by the federal government. Perhaps more far-reaching than the immediate lost of their tiny deposits, was the deadening effect the bank’s closure had on many of the depositors’ hopes and dreams for a brighter future. The bank’s demise left bitter feelings of betrayal, abandonment, and distrust of the American banking system that would remain in the African-American community for many years. While half of the depositors eventually received about three-fifths of the value of their accounts, others received nothing. Some depositors and their descendants spent more than thirty years petitioning Congress for reimbursement for losses.”

Was this bank not too big to fail?

Then, with the Compromise of 1877, Reconstruction itself was allowed to fail as politicians worked out a scheme to resolve the disputed election of 1876: Rutherford B. Hayes could have the presidency if the federal government finished withdrawing the troops from the South who had helped protect black interests there.

Everyone knew where this would lead, and that is precisely where it led: States across the South, where 90 percent of black people lived, began to call constitutional conventions, beginning with Mississippi in 1890, to enshrine white supremacy into the DNA of those states.

As the historian Jim Loewen has written, one delegate at the convention said: “Let’s tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the universe. We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this will answer.”

As Loewen put it, Confederates might have lost the Civil War in 1865, but they “won the Civil War in 1890.”

These new constitutions laid the groundwork for another 75 years or so of legal racial oppression under Jim Crow in which black people were regularly terrorized, excluded and oppressed. And this says nothing of mass incarceration, which sprung up when Jim Crow fell.

None of this is fair or right!

For a vast majority of black people’s time in this country, they have been suffering under an oppression operating on all levels of government — local, state and federal.

It is absolutely a good idea for America to think about how to make that right, to think about how to repair the damage it did, to think about how to do what is morally just.

And the idea that too much time has passed makes a mockery of morality. You can’t use having not done something at a better time as an argument that a later time can never be the right time.

Furthermore, this is not about individual guilt or shame but rather about collective responsibility and redemption. America needs to set its soul right.

The paying of reparations isn’t at all an outlandish idea. To the contrary, it’s an exceedingly reasonable proposition. Most of all, it’s right.

Opinion | Reparations: Reasonable and Right

It is America’s responsibility to undo the trauma it has inflicted upon black people for hundreds of years.

By Charles M. Blow

Opinion Columnist

- June 19, 2019

Carolyn Smith, a descendant of a slave, gestures toward gravestones of other descendants of enslaved people in Houma, La.CreditClaire Vail/American Ancestors, via New England Historic Genealogical Society, via Associated Press

Image

Carolyn Smith, a descendant of a slave, gestures toward gravestones of other descendants of enslaved people in Houma, La.CreditCreditClaire Vail/American Ancestors, via New England Historic Genealogical Society, via Associated Press

This week, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was asked his opinion on the paying of reparations to the descendants of slavery in America, and he came down solidly on the side of “no” and on the side of being intentionally obtuse.

Here is his answer in full:

“I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago, for whom none of us currently are responsible, is a good idea. We’ve tried to deal with our original sin of slavery by fighting a civil war, by passing landmark civil rights legislation. We’ve elected an African-American president. I think we’re always a work in progress in this country, but no one currently alive was responsible for that.

“And, I don’t think we should be trying to figure out how to compensate for it. First of all, it would be pretty hard to figure out who to compensate. We’ve had waves of immigrants as well who come to the country and experienced dramatic discrimination of one kind or another. So no, I don’t think reparations are a good idea.”

Everything McConnell said was fundamentally wrong — factually and morally.

Let’s start at the beginning: Chattel slavery in America is not merely “something that happened” 150 years ago. This year happens to be the 400th anniversary of when the first enslaved African arrived on our shores, and slavery became an indescribably horrific institution that thrived for nearly 250 years.

And the unpaid, unrewarded labor of those enslaved Africans is in large part what made America an economic powerhouse, and now one of the wealthiest countries in the world. And yet, the enslaved reaped none of the benefits of the wealth they created.

Does that sound fair or right?

Here it is important to point out that reparations are not only about the institution of slavery, but also about the century of oppression, a form of semi-slavery that came in its wake through racial terror, black codes and Jim Crow.

From the very beginning, emancipation wasn’t whole. During slavery, the enslaved were not counted as fully human — they were to be counted as three-fifths of a person as set forth in the Constitution — but the Supreme Court’s horrendous decision in the Dred Scott v. Sanford case confirmed that black people were not and could not become citizens of this country.

In the introduction to what remains a jaw-dropping decision, the author writes:

“The doctrine of 1776, that all (white) men ‘are created free and equal,’ is universally accepted and made the basis of all our institutions, State and National, and the relations of citizenship — the rights of the individual — in short, the status of the dominant race, is thus defined and fixed for ever.”

Black people would not be considered citizens until the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, but the 13th Amendment, ratified three years earlier, the year the Civil War ended, had already left a backdoor for quasi reimposition of slavery, stating, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

That exception was just the backdoor that many in power needed, leading to further abominations, like convict leasing. As the Equal Justice Initiativehas explained:

“After the Civil War, slavery persisted in the form of convict leasing, a system in which Southern states leased prisoners to private railways, mines and large plantations. While states profited, prisoners earned no pay and faced inhumane, dangerous and often deadly work conditions. Thousands of black people were forced into what authors have termed ‘slavery by another name’ until the 1930s.”

Does that sound fair or right?

When slavery ended, many slaves thought that they would receive 40 acres and a mule; instead, they got pestilence and starvation. In the eyes of America, all their labor had earned them nothing.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. touched on this gross failure of America in speeches just before he died and in advance of his planned Poor People’s Campaign, saying:

“At the same time that America refused to give the Negro any land, through an act of Congress, our government was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and Midwest, which meant that it was willing to undergird its white peasants from Europe with an economic floor. But not only did they give the land, they built land grant colleges, with government money, to teach them how to farm. Not only that, they provided county agents to further their expertise in farming. Not only that, they provided low interest rates in order that they could mechanize their farms. Not only that, today many of these people are receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies, not to farmand they are the very people telling the black man that he ought to lift himself by his own boot straps.”

King finished:

“Now, when we come to Washington, in this campaign, we’re coming to get our check.”

The enslaved were freed into an epidemic of sickness and death.

The historian Jim Downs estimatesthat “at least one quarter of the four million former slaves got sick or died between 1862 and 1870,” as The New York Times pointed out when his book, “Sick From Freedom,” was released in 2012.

There was no medical infrastructure — or educational or financial, for that matter — to support them. The federal government said it was the states’ responsibility, and the states shirked it, saying, in part, that they had enough to handle, with thousands of wounded soldiers returning. So, the bodies fell and the tombstones sprouted.

Does any of this sound fair or right to you?

In an 1888 speech, Frederick Douglass would blast America’s faux emancipation of black people, saying:

“I admit that the Negro, and especially the plantation Negro, the tiller of the soil, has made little progress from barbarism to civilization, and that he is in a deplorable condition since his emancipation. That he is worse off, in many respects, than when he was a slave, I am compelled to admit, but I contend that the fault is not his, but that of his heartless accusers. He is the victim of a cunningly devised swindle, one which paralyzes his energies, suppresses his ambition, and blasts all his hopes; and though he is nominally free he is actually a slave. I here and now denounce his so-called emancipation as a stupendous fraud — a fraud upon him, a fraud upon the world.”

During Reconstruction, not only was the Freedmen’s Bureau established, so was the Freedman’s Bank, in part because white banks wouldn’t do business with black people. After the bank had been run into the ground by mismanagement, Douglass was brought in as president to save it. But it was too late. Just three months later the bank was allowed to fail.

As the National Archives put it:

“The closure of Freedman’s Bank devastated the African-American community. An idea that began as a well-meaning experiment in philanthropy had turned into an economic nightmare for tens of thousands of African Americans who had entrusted their hard-earned money to the bank. Contrary to what many of its depositors were led to believe, the bank’s assets were not protected by the federal government. Perhaps more far-reaching than the immediate lost of their tiny deposits, was the deadening effect the bank’s closure had on many of the depositors’ hopes and dreams for a brighter future. The bank’s demise left bitter feelings of betrayal, abandonment, and distrust of the American banking system that would remain in the African-American community for many years. While half of the depositors eventually received about three-fifths of the value of their accounts, others received nothing. Some depositors and their descendants spent more than thirty years petitioning Congress for reimbursement for losses.”

Was this bank not too big to fail?

Then, with the Compromise of 1877, Reconstruction itself was allowed to fail as politicians worked out a scheme to resolve the disputed election of 1876: Rutherford B. Hayes could have the presidency if the federal government finished withdrawing the troops from the South who had helped protect black interests there.

Everyone knew where this would lead, and that is precisely where it led: States across the South, where 90 percent of black people lived, began to call constitutional conventions, beginning with Mississippi in 1890, to enshrine white supremacy into the DNA of those states.

As the historian Jim Loewen has written, one delegate at the convention said: “Let’s tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the universe. We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this will answer.”

As Loewen put it, Confederates might have lost the Civil War in 1865, but they “won the Civil War in 1890.”

These new constitutions laid the groundwork for another 75 years or so of legal racial oppression under Jim Crow in which black people were regularly terrorized, excluded and oppressed. And this says nothing of mass incarceration, which sprung up when Jim Crow fell.

None of this is fair or right!

For a vast majority of black people’s time in this country, they have been suffering under an oppression operating on all levels of government — local, state and federal.

It is absolutely a good idea for America to think about how to make that right, to think about how to repair the damage it did, to think about how to do what is morally just.

And the idea that too much time has passed makes a mockery of morality. You can’t use having not done something at a better time as an argument that a later time can never be the right time.

Furthermore, this is not about individual guilt or shame but rather about collective responsibility and redemption. America needs to set its soul right.

The paying of reparations isn’t at all an outlandish idea. To the contrary, it’s an exceedingly reasonable proposition. Most of all, it’s right.

Opinion | Reparations: Reasonable and Right

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Atlanta's First Black Millionaire

Alonzo Franklin Herndon (June 26, 1858 Walton County, Georgia – July 21, 1927)

Alonzo Franklin Herndon (June 26, 1858 Walton County, Georgia – July 21, 1927)

was an African-American entrepreneur and businessman in Atlanta, Georgia. Born into slavery, he became one of the first African-American millionaires in the United States, first achieving success by owning and operating three large barber shops in the city that served prominent white men. In 1905 he became the founder and president of what he built to be one of the United States' most well-known and successful African-American businesses, the Atlanta Family Life Insurance Company (Atlanta Life).

Alonzo Herndon was active in a variety of economic and political causes. He was a founding member of Booker T. Washington‘s National Negro Business League in 1900. Five years later he was one of the original members of the W.E.B. DuBois-led Niagara Movement. Herndon also used his wealth to support local institutions and causes, such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), Atlanta University, the First Congregational Church, the Southview Cemetery, and the Atlanta State Savings Bank.

Inoculation was introduced to America by a slave.

Few details are known about the birth of Onesimus, but it is assumed he was born in Africa in the late seventeenth century before eventually landing in Boston. One of a thousand people of African descent living in the Massachusetts colony, Onesimus was a gift to the Puritan church minister Cotton Mather from his congregation in 1706.

Onesimus told Mather about the centuries old tradition of inoculation practiced in Africa. By extracting the material from an infected person and scratching it into the skin of an uninfected person, you could deliberately introduce smallpox to the healthy individual making them immune. Considered extremely dangerous at the time, Cotton Mather convinced Dr. Zabdiel Boylston to experiment with the procedure when a smallpox epidemic hit Boston in 1721 and over 240 people were inoculated. Opposed politically, religiously and medically in the United States and abroad, public reaction to the experiment put Mather and Boylston’s lives in danger despite records indicating that only 2% of patients requesting inoculation died compared to the 15% of people not inoculated who contracted smallpox.

Onesimus’ traditional African practice was used to inoculate American soldiers during the Revolutionary War and introduced the concept of inoculation to the United States

Few details are known about the birth of Onesimus, but it is assumed he was born in Africa in the late seventeenth century before eventually landing in Boston. One of a thousand people of African descent living in the Massachusetts colony, Onesimus was a gift to the Puritan church minister Cotton Mather from his congregation in 1706.

Onesimus told Mather about the centuries old tradition of inoculation practiced in Africa. By extracting the material from an infected person and scratching it into the skin of an uninfected person, you could deliberately introduce smallpox to the healthy individual making them immune. Considered extremely dangerous at the time, Cotton Mather convinced Dr. Zabdiel Boylston to experiment with the procedure when a smallpox epidemic hit Boston in 1721 and over 240 people were inoculated. Opposed politically, religiously and medically in the United States and abroad, public reaction to the experiment put Mather and Boylston’s lives in danger despite records indicating that only 2% of patients requesting inoculation died compared to the 15% of people not inoculated who contracted smallpox.

Onesimus’ traditional African practice was used to inoculate American soldiers during the Revolutionary War and introduced the concept of inoculation to the United States

One in four cowboys was Black, despite the stories told in popular books and movies.

In fact, it's believed that the real “Lone Ranger” was inspired by an African American man named Bass Reeves. Reeves had been born a slave but escaped West during the Civil War where he lived in what was then known as Indian Territory. He eventually became a Deputy U.S. Marshal, was a master of disguise, an expert marksman, had a Native American companion, and rode a silver horse. His story was not unique however.

In the 19th century, the Wild West drew enslaved Blacks with the hope of freedom and wages. When the Civil War ended, freedmen came West with the hope of a better life where the demand for skilled labor was high. These African Americans made up at least a quarter of the legendary cowboys who lived dangerous lives facing weather, rattlesnakes, and outlaws while they slept under the stars driving cattle herds to market.

While there was little formal segregation in frontier towns and a great deal of personal freedom, Black cowboys were often expected to do more of the work and the roughest jobs compared to their white counterparts. Loyalty did develop between the cowboys on a drive, but the Black cowboys were typically responsible for breaking the horses and being the first ones to cross flooded streams during cattle drives. In fact, it is believed that the term “cowboy” originated as a derogatory term used to describe Black “cowhands.”

In fact, it's believed that the real “Lone Ranger” was inspired by an African American man named Bass Reeves. Reeves had been born a slave but escaped West during the Civil War where he lived in what was then known as Indian Territory. He eventually became a Deputy U.S. Marshal, was a master of disguise, an expert marksman, had a Native American companion, and rode a silver horse. His story was not unique however.

In the 19th century, the Wild West drew enslaved Blacks with the hope of freedom and wages. When the Civil War ended, freedmen came West with the hope of a better life where the demand for skilled labor was high. These African Americans made up at least a quarter of the legendary cowboys who lived dangerous lives facing weather, rattlesnakes, and outlaws while they slept under the stars driving cattle herds to market.

While there was little formal segregation in frontier towns and a great deal of personal freedom, Black cowboys were often expected to do more of the work and the roughest jobs compared to their white counterparts. Loyalty did develop between the cowboys on a drive, but the Black cowboys were typically responsible for breaking the horses and being the first ones to cross flooded streams during cattle drives. In fact, it is believed that the term “cowboy” originated as a derogatory term used to describe Black “cowhands.”

Esther Jones was the real Betty Boop

The iconic cartoon character Betty Boop was inspired by a Black jazz singer in Harlem. Introduced by cartoonist Max Fleischer in 1930, the caricature of the jazz age flapper was the first and most famous sex symbol in animation. Betty Boop is best known for her revealing dress, curvaceous figure, and signature vocals “Boop Oop A Doop!” While there has been controversy over the years, the inspiration has been traced back to Esther Jones who was known as “Baby Esther” and performed regularly in the Cotton Club during the 1920s.

Baby Esther’s trademark vocal style of using “boops” and other childlike scat sounds attracted the attention of actress Helen Kane during a performance in the late 1920s. After seeing Baby Esther, Helen Kane adopted her style and began using “boops” in her songs as well. Finding fame early on, Helen Kane often included this “baby style” into her music. When Betty Boop was introduced, Kane promptly sued Fleischer and Paramount Publix Corporation stating they were using her image and style. However video evidence came to light of Baby Esther performing in a nightclub and the courts ruled against Helen Kane stating she did not have exclusive rights to the “booping” style or image, and that the style, in fact, pre-dated her.

Baby Esther’s “baby style” did little to bring her mainstream fame and she died in relative obscurity but a piece of her lives on in the iconic character Betty Boop.

The iconic cartoon character Betty Boop was inspired by a Black jazz singer in Harlem. Introduced by cartoonist Max Fleischer in 1930, the caricature of the jazz age flapper was the first and most famous sex symbol in animation. Betty Boop is best known for her revealing dress, curvaceous figure, and signature vocals “Boop Oop A Doop!” While there has been controversy over the years, the inspiration has been traced back to Esther Jones who was known as “Baby Esther” and performed regularly in the Cotton Club during the 1920s.

Baby Esther’s trademark vocal style of using “boops” and other childlike scat sounds attracted the attention of actress Helen Kane during a performance in the late 1920s. After seeing Baby Esther, Helen Kane adopted her style and began using “boops” in her songs as well. Finding fame early on, Helen Kane often included this “baby style” into her music. When Betty Boop was introduced, Kane promptly sued Fleischer and Paramount Publix Corporation stating they were using her image and style. However video evidence came to light of Baby Esther performing in a nightclub and the courts ruled against Helen Kane stating she did not have exclusive rights to the “booping” style or image, and that the style, in fact, pre-dated her.

Baby Esther’s “baby style” did little to bring her mainstream fame and she died in relative obscurity but a piece of her lives on in the iconic character Betty Boop.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

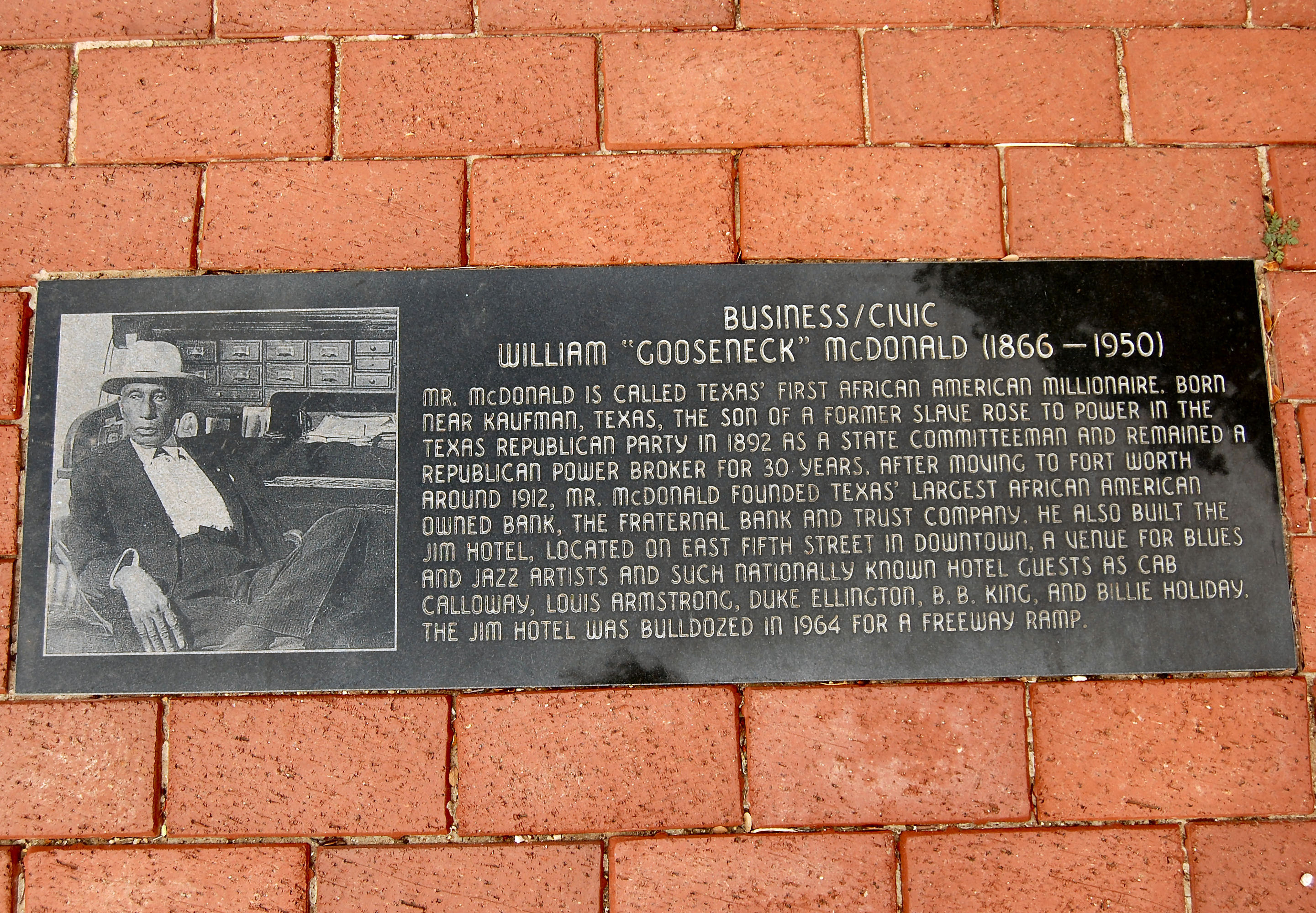

William Madison McDonald (June 22, 1866 – July 5, 1950),

nicknamed "Gooseneck Bill", was an African-American politician, businessman, and banker of great influence in Texas during the late nineteenth century. Part of the Black and Tan faction, by 1892 he was elected to the Republican Party of Texas's state executive committee, as temporary chairman in 1896, and as permanent state chairman in 1898.

During this period, McDonald was also elected as top leader of two black fraternal organizations, serving as Grand Secretary of the state's black Masons for 50 years. In 1906 he founded Fort Worth's first African-American-owned bank as an enterprise of the state Masons; under his management, the bank survived the Great Depression.[1] The black chapters of Masons banked with him, McDonald made loans to black businessmen, and he became probably the first black millionaire in Texas.[2]

Issac Hayes‘ “Theme From Shaft” was released in 1971, highlighting the tale of the crime-fighting blaxploitation hero, John Shaft. Hayes was given the Best Original Song award in 1972 and it made him the first African-American to win an Oscar for any non-acting category. Hayes was also the first person to win the award who also wrote and sang the winning song.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

William Henry Ellis (1864–1923)

william Henry Ellis, influential African-American entrepreneur, stockbroker, and proponent of the African-American emigration movement of the 1890s and early 1900s

was born a slave to Charles and Margaret Ellis on June 15, 1864. His parents had been brought by Joseph Weisiger from Kentucky to Texas in 1853. In 1870 the Ellis parents had gained their freedom and relocated to Victoria, Texas, where they established a home for themselves and their seven children.

In his youth, William Henry Ellis attended school in Victoria with his sister, Fannie, while his other siblings held full-time jobs as laborers or servants. Sometime during his teenage years, Ellis learned to speak fluent Spanish.

During his early twenties, Ellis was employed by William McNamara, a cotton and hide dealer, and constantly conducted business with Spanish-speaking businessmen. Eventually, Ellis made a name for himself in the trade. Around 1887, Ellis settled permanently in San Antonio, Texas, and began calling himself “Guillermo Enrique Eliseo,” spreading a fabricated story of his Cuban and Mexican ancestry in newspapers and social circles to conceal his real racial identity, thus enjoying some of the freedoms other African Americans could not experience at the time. He balanced these two identities for the rest of his life.

By the early 1890s, Ellis was swept into Texas politics. In 1888 he gave a speech in support of Norris Wright Cuney that landed Ellis an appointment to the Texas Republican Party’s Committee on Resolutions. By 1892, Ellis was nominated to represent the 83rd District in the Texas Legislature but lost the election to A.G. Kennedy, a white Democrat. Ellis would never seek public office again.

As time went on, Ellis began embracing ideas of African American colonization abroad, especially in Mexico. He was once quoted as saying, “Mexico has no race prejudice from a social standpoint.” Twice during the 1890s, Ellis attempted to create a colony for blacks in Mexico from the southern United States. Both attempts would fail. The first, started in 1889, fell through by 1891 due to lack of financial support and backing from the Mexican government. The second, in 1895, was an exodus of nearly eight hundred people from Tuscaloosa, Alabama, that failed when several cases of smallpox broke out after settlement in near Tlahualilo in northern Mexico, forcing almost all to return to the United States.

Ellis eventually moved to New York City, New York where he was the president of a series of mining and rubber companies, all heavily invested in Mexico. In 1903 after starting a family of his own at age thirty-nine, Ellis traveled to Ethiopia and established unofficial economic ties in a visit with King Menilik. Ellis returned to New York in 1904 and bought a seat on Wall Street. By 1910, facing economic troubles, Ellis sold his seat and moved his family to Mexico, where he would spend the rest of his days.

William Henry Ellis died at the age of fifty-nine on September 24, 1923, in Mexico City, Mexico.

.

.

The Strange Career of William Ellis: Texas Slave to Mexican Millionaire

The odds were certainly against William Henry Ellis, who was born into slavery on a Texas cotton plantation near the Mexico border.

But a combination of sheer moxie, an ability to speak Spanish and an olive skin allowed Ellis to reinvent himself. By the turn of the 20th century, he was Guillermo Enrique Eliseo, a successful Mexican entrepreneur with an office on Wall Street, an apartment on Central Park West and business dealings with companies and corporations halfway around the world.

His unusual life story is told in a new book titled The Strange Career of William Ellis: The Texas Slave Who Became a Mexican Millionaire by Karl Jacoby, a professor in the history department and the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race. Ellis “learned how to be what people wanted him to be, and how to be sure that people would see what they want to see,” Jacoby said.

Jacoby came across this larger-than-life character 20 years ago, when “he introduced himself to me in the archives.” One of the scholar’s research interests is the U.S.-Mexico border. “Even though it’s geographically peripheral, it’s actually quite central to both countries,” he said. “The borderlands become very important to how ideas of race are shaped in both countries. All these questions about immigration and who is an American get played out at the border.”

When Jacoby was a graduate student at Yale, his advisor encouraged him to look in old U.S. State Department records for anything interesting regarding the border. As Jacoby perused the pages and pages of dry documents, he came across an 1895 report about a businessman trying to bring African American sharecroppers from Alabama to work on Mexican plantations.

That’s unusual, he thought; everyone thinks of emigration going in the other direction. But it made sense; in the 1890s, southern states were instituting Jim Crow laws and some African Americans were looking farther south for freedom since Mexico had no formal segregation. The relocation effort failed, but Jacoby wanted to know who the man was behind the idea.

The difficulty of accessing data, much of it on microfilm, made a thorough search difficult, so Jacoby put aside this intriguing character, William Ellis, and wrote other works on border history, including Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History.

Ellis was hard to find for good reason. He was in the midst of transforming himself into Eliseo, erasing his blackness in the eyes of government officials and census takers, while maintaining it in other settings. He was aided by the advent of the railroads, which could whisk a man away from his past. “He’s a self-made man in the sense that he represents the rags-to-riches story that American culture just loves,” said Jacoby. “But he’s also self-made in the sense that he’s making up this identity for himself, and not just accepting the identity other people try to force on him.”

In the 1880s, Ellis moved to San Antonio, then the center of commercial trade with Mexico, and found a job facilitating these exchanges. Around the same time, he began introducing himself as Guillermo Enrique Eliseo, the Spanish version of his name. “For a while he has these two separate lives,” Jacoby said. “In San Antonio he’s a Mexican, and elsewhere he’s an African American.”

Not long after his sharecropper plan came to nothing, locals realized that Ellis was not Mexican; the city directory then put a C by his name, denoting “colored.” He disappeared, grew a large mustache, straightened his hair and bought an elegant wardrobe, later surfacing in New York City as a Mexican businessman at the height of the Gilded Age.

As trade opened up during the Mexican dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, Eliseo, who one State Department official at the time described as having a “hypnotic power of persuasion,” became a millionaire. He gave investors access to in-demand Mexican goods such as copper, a crucial mineral for electrification projects; rubber, for industrial uses; and vanilla for the delicious novelty, ice cream.

“One of the points I’m trying to get at in the book is that ultimately William Ellis moved between this African American identity, and this Mexican identity, which is usually treated as ‘passing’ for another race,” Jacoby said. “In the 19th century, a person could only be one or the other, but for Ellis, these identities were equally real.”

By the turn of the century, Ellis was one of the first African Americans on Wall Street. “He was born a slave in poverty and ends up living on Central Park West and having an office on Wall Street right next to J.P. Morgan,” said Jacoby. “It’s another reminder of how race is ultimately a fiction that we tell ourselves to divide people for one another. His story suggests how fluid race can truly be.”