Black Lightning

Superstar

A gifted tennis player, Althea Gibson set numerous records by being the first African American to win at some of the most prestigious tennis courts in the world. In times of racial segregation Althea Gibson's most difficult opponent was racism and ignorance. It wasn't until 1950 that 23 year old Althea Gibson became the first African American allowed to compete in the U.S. Nationals. In 1956 Gibson became the first African American to win the French open and the following year she became the first African American, male or female to win a championship at Wimbledon. That same year she won her first U.S. National tournament. In 1958 Althea Davis repeated the previous year's feats and won both Wimbledon and the U.S. National again!

A 5-foot-11 right-hander, Althea Gibson had a strong serve and preferred to be on the attack. An athletic woman, she had good foot speed, which allowed her to cover the court. As the years went on, she became more consistent from the baseline. Including six doubles titles, she won a total of 11 Grand Slam events on her way to the International Tennis Hall of Fame and the International Women's Sports Hall of Fame. Althea Davis became the first black woman to be named Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press, not once but twice.

Althea Gibson was born in Silver South Carolina on August 25, 1927, to Daniel and Annie Bell Gibson. At the age of three, Gibson moved north with her family to Harlem, New York. With her family on welfare, Althea Gibson was sometimes a client for the Society to prevent cruelty to children. Harlem was a rough neighborhood and Althea was often in fights. Skipping school and getting into trouble, she often ran away from home. Althea spent her spare time hanging out at public recreation buildings, often playing table tennis. Musician Buddy Walker, worked for the city's recreational program in the summer to supplement his income. He noticed her playing table tennis, and thought she might do well in tennis, and brought her to the Harlem River Tennis Courts, where she learned the game and began to excel. Soon the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club, where upper-class African-Americans played was interested in her game, raising the money to pay her member fees into the club, they also covered the expense of tennis lessons from Fred Johnson. She began her amateur tennis career in 1942.

Winning the girls' singles event at the American Tennis Association's New York State Tournament in 1942, Althea repeated her victory in 1944 and 1945, but had still only competed against other African Americans.

Wanting to further her game Althea Gibson found the support she needed to succeed. Dr. Hubert Eaton and Dr. Walter Johnson, two African-American physicians who loved tennis and helped many young African-Americans who wanted to play the game came to Althea Gibson's aid. The two men not only paid all of her expenses during this period, they also taught her the etiquette of tennis and the rules of living in a middle class family.

In Wilmington North Carolina she lived at Dr. Eaton’s home with his family during the school year and attended Williston High School. He coached her and taught her tennis etiquette. Althea lived in Lynchburg, Virginia with Dr. Johnson’s family during the summers, and played tennis through the American Tennis Association, traveling to tournaments with Dr. Johnson. Not only did she complete high school, Gibson went on to attend Florida A & M University in Tallahassee, graduating in 1953.

Continuing to enter and win the ATA tournaments, Althea Gibson was still not allowed to compete against white woman in tennis. In July of 1950, American Lawn Tennis Magazine published an editorial by tennis champ Alice Marble, urging the tennis world to give Althea Gibson the opportunity to play in its tournaments. "If Althea Gibson represents a challenge to the present crop of players, then it's only fair that they meet this challenge on the courts," Marble wrote. The tennis world listened and that same year Althea Gibson was allowed to compete in the U.S. Nationals.

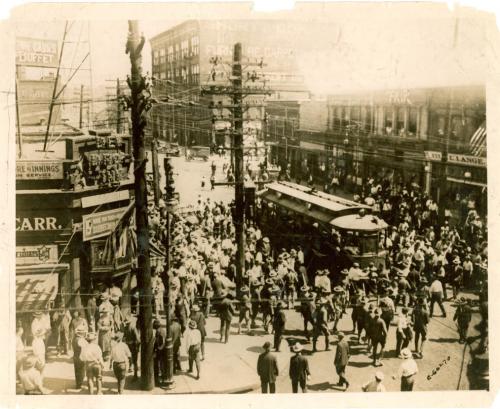

Gibson defeated Barbara Knapp in straight sets. Her second-round match on the grass of Forest Hills was against Louise Brough, who had won the previous three Wimbledon's. After being routed 6-1 in the first set, Gibson recovered to win the second set 6-3 and led 7-6 in the third when a thunderstorm struck, halting the match. When it resumed the next day, Gibson dropped three straight games to lose the match.

Learning to adjust to the higher level of competition, Althea Gibson quickly rose to the top and was ranked in the world top ten women's tennis players from 1956 through 1958, reaching a career high of No. 1 in those rankings in 1957 and 1958. Gibson was included in the year-end top ten rankings issued by the United States Tennis Association in 1952 and 1953 and from 1955 through 1958. After winning back to back titles at both the U.S. Nationals and Wimbledon, along with her victory at the French Open, Althea Gibson became a household name. She was the top-ranked U.S. player in 1957 and 1958. In 1958, she appeared as the celebrity challenger on the TV panel show "What's My Line?".