Black Lightning

Superstar

Austin Steward, author, businessman, abolitionist, and temperance leader, was born a slave in Prince William County, Virginia to Robert and Susan Steward sometime around 1793. By the age of seven he was working as a house slave on the plantation of Capt. William Helm. The Helm family left Virginia, after being involved in several embarrassing scandals, settled in upstate New York. Austin Steward went with them along with many other slaves.

While living in upstate New York, Steward taught himself to read in secrecy, for which he was severely beaten and his books burned. This beating, along with many others he received, gave him severe reoccurring head pains from which he suffered for the rest of his life. In 1814 Steward sought the help of the New York Manumission Society to secure his freedom. An agent of the society informed Steward that he was legally free on the grounds that he had been rented out by Capt. Helm to other farmers, which violated New York State’s slave laws. The agent told Steward to continue his services to Capt. Helm until the agent could fully provide Steward with everything he would need to make his freedom official.

After being told that freedom was an option, Steward ran away to Rochester, New York before his status was legally determined. After running away, Steward worked odd jobs for various people until he saved up enough money to open his own meat market. The meat market became profitable allowing Steward to acquire considerable property in Rochester, and the surrounding area. By this time Capt. Helm had lost all of his property and become so poor that he was living off of the charity of the town. He tried to sue Steward to take both his money and his freedom but died before the case could go to trial.

In 1830, Steward joined the temperance movement and stopped selling all hard-liquors at his Rochester general store. Throughout his life he would lecture and write extensively for the temperance movement.

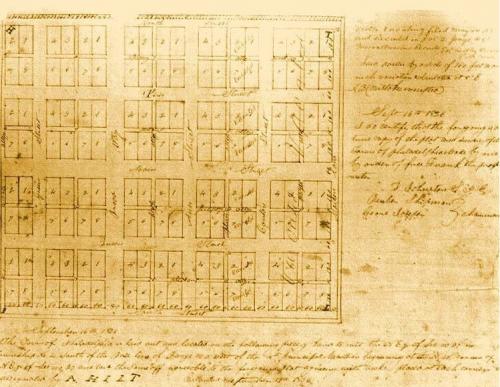

In 1831, Steward was invited to come help a colony in Canada founded by African-Americans fleeing the Ohio Black Codes. Upon arrival Steward was elected President of the Board of Managers for the colony, which he named Wilberforce, after the English abolitionist William Wilberforce.

The colony failed due mostly to massive embezzlement by its fundraisers. Steward tried to end to the embezzlement which generated several assassination attempts against him. Eventually he gave up on Wilberforce Colony and returned to Rochester in 1837, a far poorer man.

Back in Rochester he once again devoted himself to business as well as his many temperance and abolitionist causes. He also wrote the memoir; Twenty-Two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman which detailed both his early life as a slave as well as his struggles at Wilberforce Colony.

Austin Steward died of typhoid fever on February 15, 1869 and was buried in Canandaigua, New York.