In the mid-1860s, an African-American artist arrived at the home of England’s poet laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, on the Isle of Wight. He brought with him his most celebrated painting,

Land of the Lotus Eaters, based on a poem by the great man of letters.

Tennyson was delighted with the image. “Your landscape,” he proclaimed, “is a land in which one loves to wander and linger.”

The artist, Robert S. Duncanson, known in America as “the greatest landscape painter in the West,” now stood poised to conquer England.

"He invented a unique place for himself that no other African-American had attained at that time,” says art historian Claire Perry, curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibit “The Great American Hall of Wonders.” “It was a position as an eminent artist recognized both within the United States and abroad as a master." Duncanson’s painting

Landscape with Rainbow is in the exhibit, which closes January 8, 2012.

Though dozens of Duncanson’s paintings survive in art institutions and private collections, after his death in 1872, his name faded into obscurity. But an exhibition of his paintings at the Cincinnati Art Museum on the centenary of his death helped restore his renown. Since then, his work has been the subject of several books, including art historian Joseph Ketner’s

The Emergence of the African-American Artist, as well as the recent exhibition “Robert S. Duncanson: The Spiritual Striving of the Freedmen's Sons,” at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in Catskill, New York.

“Duncanson’s progression from a humble housepainter to recognition in the arts,” writes Ketner, “signaled the emergence of the African-American artist from a people predominantly relegated to laborers and artisans.”

Duncanson was born circa 1821 in Fayette, New York, into a family of free African-Americans skilled in carpentry and house painting. When he was a boy, the family moved to Monroe, Michigan, where he took up the family trade as a teenager, advertising a new business as a painter and glazier in the

Monroe Gazette. But Duncanson, who taught himself fine art by copying prints and drawing still lifes and portraits, was not content to remain a tradesman. He soon moved to Cincinnati, then known as the "Athens of the West" for its abundance of art patrons and exhibition venues.

To make ends meet, he essentially became an itinerant artist, looking for work between Cincinnati, Monroe and Detroit. But in 1848, his career received a major boost when he was commissioned by anti-slavery activist Charles Avery to paint the landscape,

Cliff Mine,

Lake Superior. The association led to a lifelong relationship with abolitionists and sympathizers who wanted to support black artists.

The commission also ignited a passion in Duncanson for landscape painting, which led to a friendship with William Sonntag, one of Cincinnati's leading practitioners of the Hudson River School of landscape painting. In 1850, the

Daily Cincinnati Gazette reported, "In the room adjoining Sonntag's, at Apollo Building, Duncanson, favorably known as a fruit painter, has recently finished a very good strong lake view."

"He had exceptional talent as an artist," says Perry. "But there was also something about his personality that made important patrons take him under their wings.” Nicholas Longworth, a horticulturalist with anti-slavery sentiments, was one of those patrons. Longworth hired him to paint eight monumental landscape murals on the panels inside the main hall of his Belmont mansion, now known as Taft Museum of Art, in Cincinnati. “These are the most ambitious and accomplished domestic mural paintings in antebellum America,” writes Ketner.

"Longworth was one of the richest men in the United States," says Perry. "He knew everyone and had connections with everyone. When he gave Duncanson this very important commission for his home, he gave him the Good Housekeeping stamp of approval."

Ever ambitious, Duncanson wanted to be the best at his profession and embarked upon a grand tour of Europe in 1853 to study the masters. His letters reveal an understated confidence: "My trip to Europe has to some extent enabled me to judge of my own talent," he wrote. "Of all the Landscapes I saw in Europe, (and I saw thousands) I do not feel discouraged . . . . Someday I will return."

Meanwhile, Cincinnati had become a hotbed of anti-slavery activity, and Duncanson appears to have supported the cause, participating in abolitionist societies and donating paintings to help raise funds. During the 1850s, Duncanson also worked as the principal artist in the city's premier daguerrean studio with owner James Presley Ball, a fellow African-American. “Both men had African-Americans living with them who listed themselves as painters or daguerreans,” says Ketner. “This was the first real aggregate cluster of an African-American community of artists in America.”

.

.

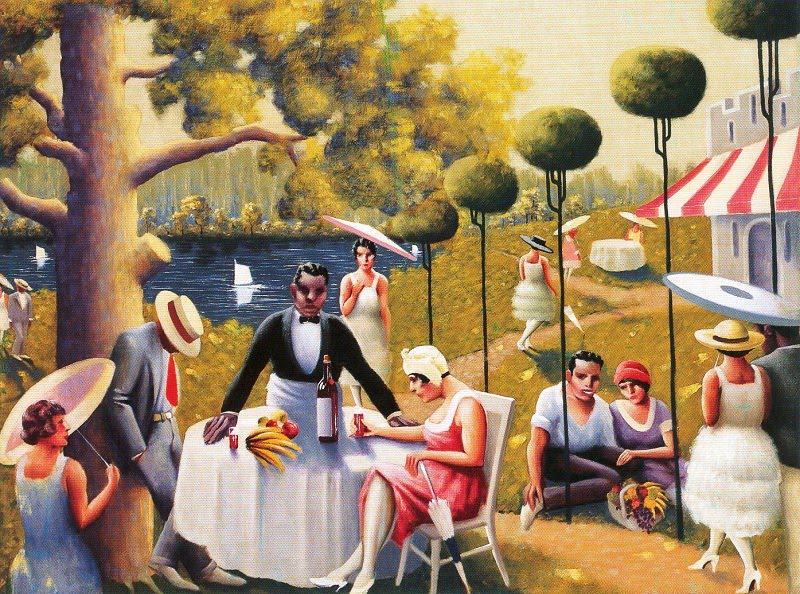

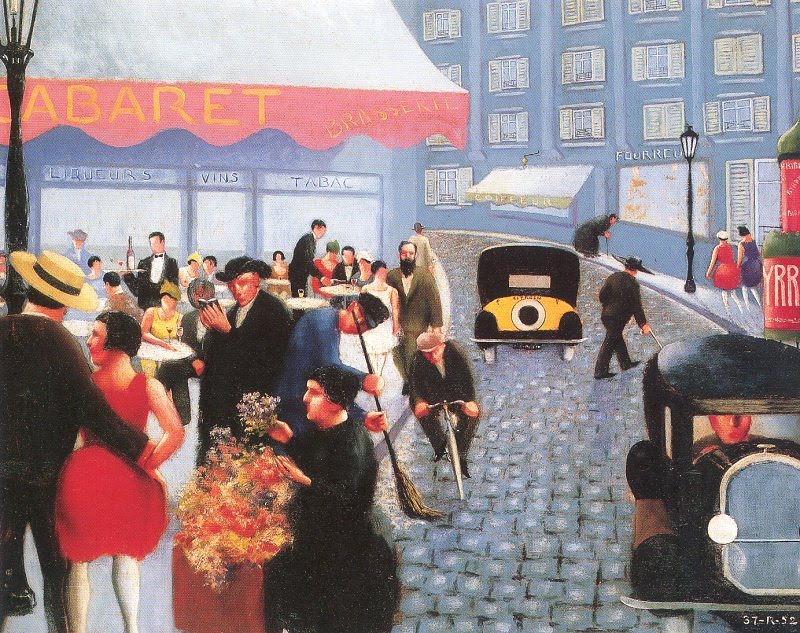

Robert Duncanson painted

Landscape with Rainbow two years after everybody thought Frederic Church’s rainbow in

Niagara could never be topped, says art historian Claire Perry. Although other artists grew skittish, “Duncanson waded right in,” she says. “It was a bold move.” (Gift of Leonard and Paula Granoff / Smithsonian American Art Museum)

.

.

Duncanson is believed to have helped create the images in the anti-slavery presentation,

Ball's Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States. (The painting itself no longer exists, but evidence suggests that it was Duncanson’s brushwork). Presented in theaters across the country, the 600-yard-wide panorama utilized narration and special sound and lighting effects to portray the horrors of human bondage from capture and trans-Atlantic passage to slave markets and escape to Canada.

In fact, after his European pilgrimage, Duncanson had declared,” I have made up my mind to paint a great picture, even if I fail." Although critics had responded favorably to Duncanson’s first post-tour effort,

Time’s Temple, it was 1858’s

Western Forest that exposed him to an international abolitionist community and helped pave the way for his return to England.

Duncanson executed his next work in the tradition of European paintings that conveyed historical, literary or other moralizing subjects. The result was

Land of the Lotus Eaters, based on Tennyson’s poem about the paradise that seduced Ulysses' soldiers. But in Duncanson’s tropical landscape, white soldiers are resting comfortably on the banks of a river, while being served by dark-skinned Americans, reflecting contemporary criticism, says Ketner, that the South had grown dependent on slave labor to support its standard of living. “He prophesied the forthcoming long and bloody Civil War,” writes Ketner, “and offered an African-American perspective.”

A reviewer at the

Daily Cincinnati Gazette proclaimed, "Mr. Duncanson has long enjoyed the enviable reputation of being the best landscape painter in the West, and his latest effort cannot fail to raise him still higher."

Duncanson decided to take his “great picture” to Europe—by way of Canada—some say to avoid having to obtain a diplomatic passport required for persons of color traveling abroad. His stopover in Canada would last more than two years.

During his stay, Duncanson helped foster a school of landscape painting, influencing Canadian artists such as Otto Jacobi, C. J. Way, and Duncanson’s pupil, Allan Edson, who would become one of the country’s formative landscape artists. He worked with the prestigious gallery of William Notman, known as the “Photographer to the Queen,” to promote arts and culture; was heralded as a “cultivator” of the arts in Canada; and was perceived as a native son. When he left for the British Isles in 1865, and stopped in Dublin to participate in the International Exposition, he exhibited in the Canadian pavilion.

In London, Duncanson’s long-awaited unveiling of

Land of the Lotus Eaters inspired lavish praise. “It is a grand conception, and a composition of infinite skill,” raved one reviewer. “This painting may rank among the most delicious that Art has given us,” he added, “but it is wrought with the skill of a master.”

Duncanson soon became the toast of Great Britain. He enjoyed the patronage of the Duchess of Sutherland, the Marquis of Westminster and other aristocrats and royals, including the King of Sweden, who purchased

Lotus Eaters. Duncanson visited the Duchess of Argyll at her castle in Scotland, and made sketches for new landscapes there and in Ireland. Finally, he had realized his longtime dream of returning to Europe and winning international acclaim.

In the midst of such praise and patronage, Duncanson abruptly left England in 1866, after only a year. He may have been eager to experience the rebirth of America now that the Civil War—and the threat posed by the slave-holding Confederacy across the Ohio border—had ended, but his reasons are unclear to art historians.

“Excitable, energetic, irrepressible are words I would apply to his personality,” says Ketner. “It’s what gave him the impetus to have these daring aspirations, but maybe that personality became troubled.”

At the height of his success and fame in the late 1860s and early 1870s, Duncanson was stricken with what was referred to as dementia. Prone to sudden outbursts, erratic behavior and delusions, by 1870, he imagined that he was possessed by the spirit of a deceased artist. Scholars suggest that the brooding mood and turbulent waters of seascapes, such as

Sunset on the New England Coast and

A Storm off the Irish Coast, reflected his disturbed mental state.

Ketner, who consulted physicians about the symptoms described by Duncanson’s contemporaries, believes his condition was caused by lead poisoning. “As a housepainter, he had dealt with large quantities of lead paint since boyhood,” says Ketner, “and then was exposed to cumulative amounts as an artist.”

While curator Perry believes the stress of straddling the chasm between white and black societies may have contributed to his mental deterioration, she continues to weigh several factors. “He did live a life of incredible stress as a successful African-American in a white-dominated world,” she says. “But people who perform at the highest level of artistic skills are also people of unusual sensitivity.”

Despite the challenges he confronted, Duncanson persevered. He opened a new studio in Cincinnati and turned his sketches of the Scottish Highlands into masterpieces, including Ellen’s

Isle, Loch Katrine, a painting inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s poem “The Lady of the Lake,” and

Pass at Leny, in which he subordinates the sentimentality of previous landscapes to more naturalistic forms. In 1871, he toured America with several historical works, priced upward of $15,000 apiece.

Even as his health failed, his passion for his work persisted. Duncanson was installing an exhibition in Detroit in October 1872 when he suffered a seizure and collapsed. He died two months later; the cause of death remains uncertain.