Dance, water and prayers: Celebrating the goddess Yemoja

Each year, the Yoruba people in Nigeria offer thanks to Yemoja, goddess of the river and mother of all other Yoruba gods. It is an important way for them to remember and celebrate their traditional roots and beliefs.

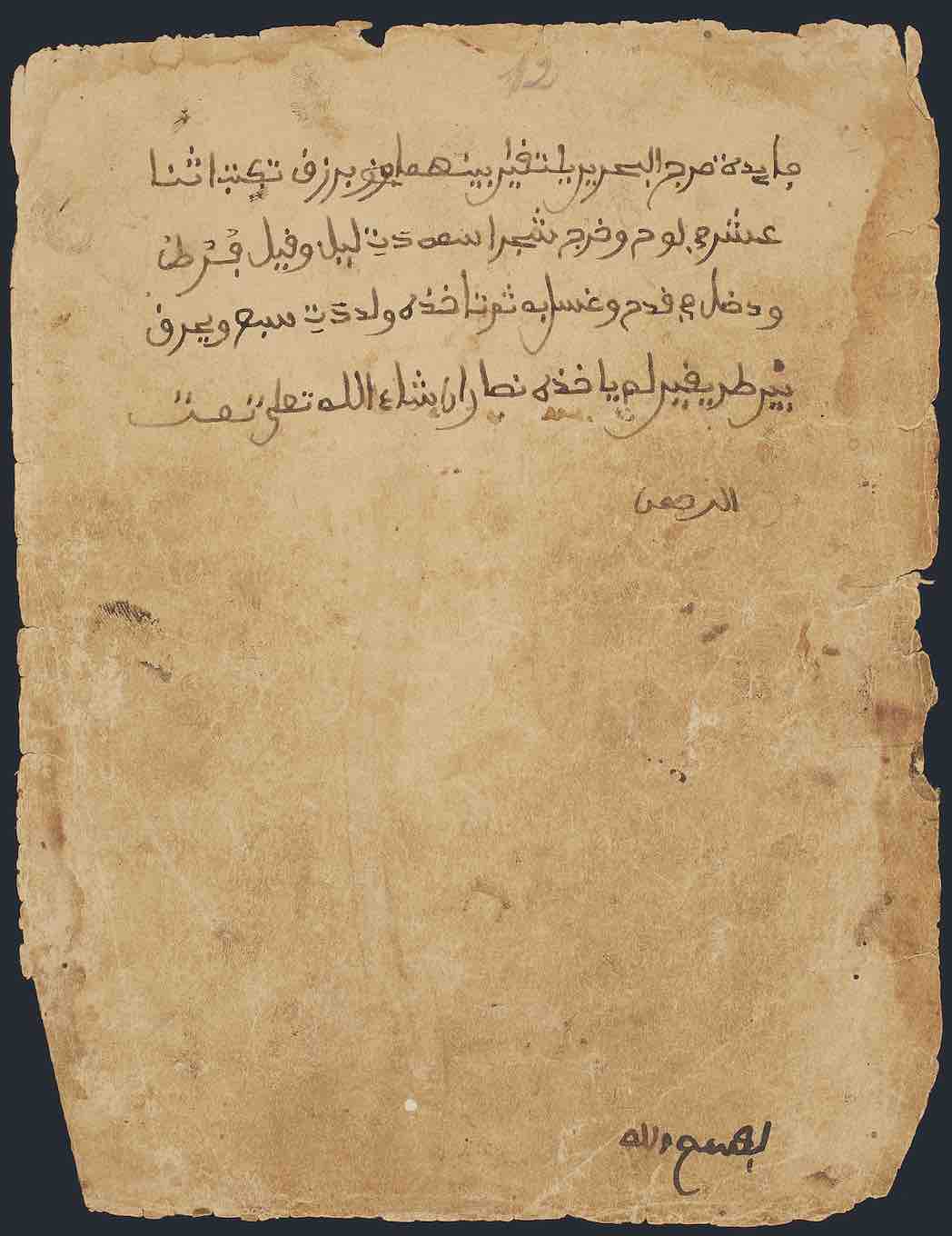

One of the Bata drummers during the procession to the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

By Femi Amogunla | 6 Dec 2020

Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria – During the annual festival to celebrate Yemoja, the goddess of the river, the day begins with music, dance and prayers. There are 400 gods – called òrìsà in the Yoruba language – each representing a force of nature. Yemoja is considered the mother of them all, such is the importance of water to life.

Yemoja devotees dance in front of the temple at Popo Ibode Yemoja, Ibadan [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

These days, most Nigerians belong to one of the two main religions, Christianity and Islam, while traditional religions, much derided during colonial times, have fallen by the wayside in many places.

But in Ibadan, where faith in all orisa – the Yoruba gods – remains joyful and strong, celebrations of the old religion continue. The 17-day-long Yemoja festival in October is as old as the Yoruba people. It has been celebrated since “time immemorial”, according to the priestess, Ifawemimo Omitonade.

October 31 is the grand finale of the Yemoja Festival in Ibadan, when different groups of orisa devotees dance to the rhythm of thrumming drums in front of the Yemoja Temple.

Inside sits Ogunleki, a 400-year-old statue of Yemoja, a woman breastfeeding a baby, 3 feet (about 1 metre) high. Devotees, young and old, sing Yoruba songs, giving thanks to the òrìsà for keeping them healthy since the previous year, and for allowing them to see another festival.

A Yemoja worshipper kneels in front of Ogunleki, a more than 400-year-old artistic portrayal of Yemoja [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

They also sing songs of prayers, trusting that they will return the following year more prosperous, and later they will proceed to the river to make their offerings and more prayers.

Chief Akinola Olaosun – ‘the river is inhabited by spirits’

Inside the temple, Chief Akinola Olaosun prepares the items to be presented to Yemoja at the river. Chief Akinola is also known as “Aare Adimula fun Odo Babalawo Ilu Ibadan”, which translates as “President of the young herbalists of Ibadan”.

Chief Akinola Olaosun during the preparation of Yemoja’s food at the temple [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

In front of him, next to the statue of Ogunleki, is an array of calabashes – large, melon-like fruit which have been hollowed out – into which he drops sacred items as offerings to the goddess. Among these are dried kola nuts into which people have spoken words of prayer to Yemoja.

After these preparations are complete at the temple, prayers are said by Chief Egbelade Omikunmi, who is the Baale Yemoja – the chief priest to Yemoja – his hands outstretched to the devotees, who respond with “Ase”, the Yoruba ending to a prayer. Then the procession to the river begins.

Baale Yemoja of Ibadan land prays for the celebrants at in front of Yemoja’s temple [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Accompanied by music, women dressed in white carry calabashes on their heads. In each calabash, there are different items – corn and beans cooked together, yam porridge and fruits – prepared for the òrìsà. Attendees follow the procession of arugba – the calabash carriers. Their destination: the nearby river. Their purpose: propitiation and prayers to Yemoja.

Chief Akinola Olaosun takes one of the calabashes containing food to Baale Yemoja for propitiation [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“The river is inhabited by spirits that we converse with,” says Chief Akinola. “We also make pledges to them yearly. So, during the festival, we redeem our pledges by giving them what is due to them.” By so doing, he explains, devotees express their gratitude for the past year and pray for a better year ahead.

Some of the attendees and devotees offer prayers to the deity as the propitiation continues in the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Because of initial fears about the spread of COVID-19 and this year’s unrest over police brutality in Nigeria, the crowd at the festival is more modest than it might have been, but more than 300 have come along nonetheless.

Ifawemimo Omitonade – Priestess

“It is good to know that people actually came and demonstrated their faith in our mother,” says Ifawemimo Omitonade, the priestess to Yemoja. As for the chief priest, the priestess is chosen by worshippers who have “consulted” with the orisa, Yemoji, through divination and prayer. Once a person has been chosen for this rank, they undergo a nine-day initiation process of rigorous self-examination to bring them closer to their chosen orisa, known as ita. Once chosen, a priest or priestess keeps his or her title for life.

Iyalorisa Omitonade uses ‘Aja’, an instrument used in invoking Yemoja’s spirit, during the propitiation process [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Iyalorisa Omitonade guides one of the calabash carriers during a procession to the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Ifawemimo, who is in her 30s, is one of those devotees dedicated to keeping the old traditions alive in this part of Nigeria. She shares the beauty of the traditional religion on social media.

Friends of the Yemoja priestess who came to celebrate with her pose for a picture just before the procession to the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“People are always of the opinion that traditionalists are fetishists … and other kinds of negativity,” she laments. She is glad, however, that young people are developing an interest in traditional religions and are demystifying them.

When the prayers at the river, at the end of the celebration, are over, Ifawemimo takes some of the water from the river in a bucket and sprinkles it on her fellow devotees. In addition to the sprinkling, some of the devotees collect some of the river water in bottles. This sacred water is considered medicinal – mixed with the water people drink or added to a bath to heal ailments.

Omintonade sprinkles water from the river on some of the attendees after the propitiation. ‘This is some form of rejuvenation and blessings from the Orisha,’ she says [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“The water is for rejuvenation and blessings from Yemoja,” Ifawemimo explains.

Foluke Akinyemi – ‘a most beautiful inheritance’

Yoruba culture enthusiast Foluke Akinyemi, who hosts the local Yoruba radio talk show, Awa Ewe which means “We, the Youth”, has come along to this year’s festival. She has been invited by Omitonade who she met through social media. Raised a Christian, she says the festival is an opportunity to reconnect with her Yoruba roots by worshipping the deities her ancestors prayed to.

‘I am happy I am part of this year’s festival … I will continue to let other this the beauty in this tradition,’ says Foluke, a culture enthusiast and radio host [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“Yoruba culture is the most beautiful inheritance,” she says. “I personally value the role Yemoja plays in the Yoruba pantheon and mythical histories. At this year’s festival, I feel connected, I feel fulfilled. I am so glad to get to know more about orisa worship and I will continue to make people see that too,” she says.

Each year, the Yoruba people in Nigeria offer thanks to Yemoja, goddess of the river and mother of all other Yoruba gods. It is an important way for them to remember and celebrate their traditional roots and beliefs.

One of the Bata drummers during the procession to the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

By Femi Amogunla | 6 Dec 2020

Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria – During the annual festival to celebrate Yemoja, the goddess of the river, the day begins with music, dance and prayers. There are 400 gods – called òrìsà in the Yoruba language – each representing a force of nature. Yemoja is considered the mother of them all, such is the importance of water to life.

Yemoja devotees dance in front of the temple at Popo Ibode Yemoja, Ibadan [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

These days, most Nigerians belong to one of the two main religions, Christianity and Islam, while traditional religions, much derided during colonial times, have fallen by the wayside in many places.

But in Ibadan, where faith in all orisa – the Yoruba gods – remains joyful and strong, celebrations of the old religion continue. The 17-day-long Yemoja festival in October is as old as the Yoruba people. It has been celebrated since “time immemorial”, according to the priestess, Ifawemimo Omitonade.

October 31 is the grand finale of the Yemoja Festival in Ibadan, when different groups of orisa devotees dance to the rhythm of thrumming drums in front of the Yemoja Temple.

Inside sits Ogunleki, a 400-year-old statue of Yemoja, a woman breastfeeding a baby, 3 feet (about 1 metre) high. Devotees, young and old, sing Yoruba songs, giving thanks to the òrìsà for keeping them healthy since the previous year, and for allowing them to see another festival.

A Yemoja worshipper kneels in front of Ogunleki, a more than 400-year-old artistic portrayal of Yemoja [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

They also sing songs of prayers, trusting that they will return the following year more prosperous, and later they will proceed to the river to make their offerings and more prayers.

Chief Akinola Olaosun – ‘the river is inhabited by spirits’

Inside the temple, Chief Akinola Olaosun prepares the items to be presented to Yemoja at the river. Chief Akinola is also known as “Aare Adimula fun Odo Babalawo Ilu Ibadan”, which translates as “President of the young herbalists of Ibadan”.

Chief Akinola Olaosun during the preparation of Yemoja’s food at the temple [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

In front of him, next to the statue of Ogunleki, is an array of calabashes – large, melon-like fruit which have been hollowed out – into which he drops sacred items as offerings to the goddess. Among these are dried kola nuts into which people have spoken words of prayer to Yemoja.

After these preparations are complete at the temple, prayers are said by Chief Egbelade Omikunmi, who is the Baale Yemoja – the chief priest to Yemoja – his hands outstretched to the devotees, who respond with “Ase”, the Yoruba ending to a prayer. Then the procession to the river begins.

Baale Yemoja of Ibadan land prays for the celebrants at in front of Yemoja’s temple [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Accompanied by music, women dressed in white carry calabashes on their heads. In each calabash, there are different items – corn and beans cooked together, yam porridge and fruits – prepared for the òrìsà. Attendees follow the procession of arugba – the calabash carriers. Their destination: the nearby river. Their purpose: propitiation and prayers to Yemoja.

Chief Akinola Olaosun takes one of the calabashes containing food to Baale Yemoja for propitiation [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“The river is inhabited by spirits that we converse with,” says Chief Akinola. “We also make pledges to them yearly. So, during the festival, we redeem our pledges by giving them what is due to them.” By so doing, he explains, devotees express their gratitude for the past year and pray for a better year ahead.

Some of the attendees and devotees offer prayers to the deity as the propitiation continues in the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Because of initial fears about the spread of COVID-19 and this year’s unrest over police brutality in Nigeria, the crowd at the festival is more modest than it might have been, but more than 300 have come along nonetheless.

Ifawemimo Omitonade – Priestess

“It is good to know that people actually came and demonstrated their faith in our mother,” says Ifawemimo Omitonade, the priestess to Yemoja. As for the chief priest, the priestess is chosen by worshippers who have “consulted” with the orisa, Yemoji, through divination and prayer. Once a person has been chosen for this rank, they undergo a nine-day initiation process of rigorous self-examination to bring them closer to their chosen orisa, known as ita. Once chosen, a priest or priestess keeps his or her title for life.

Iyalorisa Omitonade uses ‘Aja’, an instrument used in invoking Yemoja’s spirit, during the propitiation process [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Iyalorisa Omitonade guides one of the calabash carriers during a procession to the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

Ifawemimo, who is in her 30s, is one of those devotees dedicated to keeping the old traditions alive in this part of Nigeria. She shares the beauty of the traditional religion on social media.

Friends of the Yemoja priestess who came to celebrate with her pose for a picture just before the procession to the river [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“People are always of the opinion that traditionalists are fetishists … and other kinds of negativity,” she laments. She is glad, however, that young people are developing an interest in traditional religions and are demystifying them.

When the prayers at the river, at the end of the celebration, are over, Ifawemimo takes some of the water from the river in a bucket and sprinkles it on her fellow devotees. In addition to the sprinkling, some of the devotees collect some of the river water in bottles. This sacred water is considered medicinal – mixed with the water people drink or added to a bath to heal ailments.

Omintonade sprinkles water from the river on some of the attendees after the propitiation. ‘This is some form of rejuvenation and blessings from the Orisha,’ she says [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“The water is for rejuvenation and blessings from Yemoja,” Ifawemimo explains.

Foluke Akinyemi – ‘a most beautiful inheritance’

Yoruba culture enthusiast Foluke Akinyemi, who hosts the local Yoruba radio talk show, Awa Ewe which means “We, the Youth”, has come along to this year’s festival. She has been invited by Omitonade who she met through social media. Raised a Christian, she says the festival is an opportunity to reconnect with her Yoruba roots by worshipping the deities her ancestors prayed to.

‘I am happy I am part of this year’s festival … I will continue to let other this the beauty in this tradition,’ says Foluke, a culture enthusiast and radio host [Femi Amogunla/Al Jazeera]

“Yoruba culture is the most beautiful inheritance,” she says. “I personally value the role Yemoja plays in the Yoruba pantheon and mythical histories. At this year’s festival, I feel connected, I feel fulfilled. I am so glad to get to know more about orisa worship and I will continue to make people see that too,” she says.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_59edd422c0c84a879bd37670ae4f538a/internal_photos/bs/2022/j/V/c9intoRZmOmu5qhK6cCA/image.psd-13-.jpg)