And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

www.technologyreview.com

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

By

Will Douglas Heavenarchive page

March 4, 2024

SARAH ROGERS/MITTR | GETTY

Two years ago, Yuri Burda and Harri Edwards, researchers at the San Francisco–based firm OpenAI, were trying to find out what it would take to get a language model to do basic arithmetic. They wanted to know how many examples of adding up two numbers the model needed to see before it was able to add up any two numbers they gave it. At first, things didn’t go too well. The models memorized the sums they saw but failed to solve new ones.

By accident, Burda and Edwards left some of their experiments running far longer than they meant to—days rather than hours. The models were shown the example sums over and over again, way past the point when the researchers would otherwise have called it quits. But when the pair at last came back, they were surprised to find that the experiments had worked. They’d trained a language model to add two numbers—it had just taken a lot more time than anybody thought it should.

Curious about what was going on, Burda and Edwards teamed up with colleagues to study the phenomenon. They found that in certain cases, models could seemingly fail to learn a task and then all of a sudden just get it, as if a lightbulb had switched on. This wasn’t how deep learning was supposed to work. They called the behavior

grokking.

“It’s really interesting,” says Hattie Zhou, an AI researcher at the University of Montreal and Apple Machine Learning Research, who wasn’t involved in the work. “Can we ever be confident that models have stopped learning? Because maybe we just haven’t trained for long enough.”

The weird behavior has

captured the imagination of the

wider research community. “Lots of people have opinions,” says Lauro Langosco at the University of Cambridge, UK. “But I don’t think there’s a consensus about what exactly is going on.”

With hopes and fears about the technology running wild, it's time to agree on what it can and can't do.

Grokking is just one of several odd phenomena that have AI researchers scratching their heads. The largest models, and large language models in particular, seem to behave in ways textbook math says they shouldn’t. This highlights a remarkable fact about deep learning, the fundamental technology behind today’s AI boom: for all its runaway success, nobody knows exactly how—or why—it works.

“Obviously, we’re not completely ignorant,” says Mikhail Belkin, a computer scientist at the University of California, San Diego. “But our theoretical analysis is so far off what these models can do. Like, why can they learn language? I think this is very mysterious.”

The biggest models are now so complex that researchers are studying them as if they were strange natural phenomena, carrying out experiments and trying to explain the results. Many of those observations fly in the face of classical statistics, which had provided our best set of explanations for how predictive models behave.

So what, you might say. In the last few weeks, Google DeepMind has rolled out

its generative models across

most of its consumer apps. OpenAI

wowed people with Sora, its stunning new text-to-video model. And

businesses around the world are scrambling to co-opt AI for their needs. The tech works—isn’t that enough?

But figuring out why deep learning works so well isn’t just an intriguing scientific puzzle. It could also be key to unlocking the next generation of the technology—as well as getting a handle on its

formidable risks.

“These are exciting times,” says Boaz Barak, a computer scientist at Harvard University who is on secondment to

OpenAI’s superalignment team for a year. “Many people in the field often compare it to physics at the beginning of the 20th century. We have a lot of experimental results that we don’t completely understand, and often when you do an experiment it surprises you.”

Old code, new tricks

Most of the surprises concern the way models can learn to do things that they have not been shown how to do. Known as generalization, this is one of the most fundamental ideas in machine learning—and its greatest puzzle. Models learn to do a task—spot faces, translate sentences, avoid pedestrians—by training with a specific set of examples. Yet they can generalize, learning to do that task with examples they have not seen before. Somehow, models do not just memorize patterns they have seen but come up with rules that let them apply those patterns to new cases. And sometimes, as with grokking, generalization happens when we don’t expect it to.

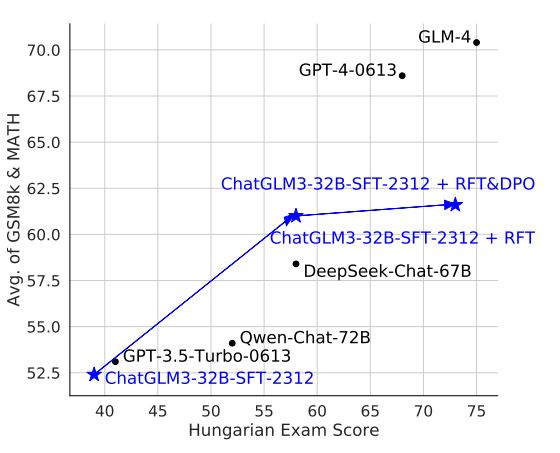

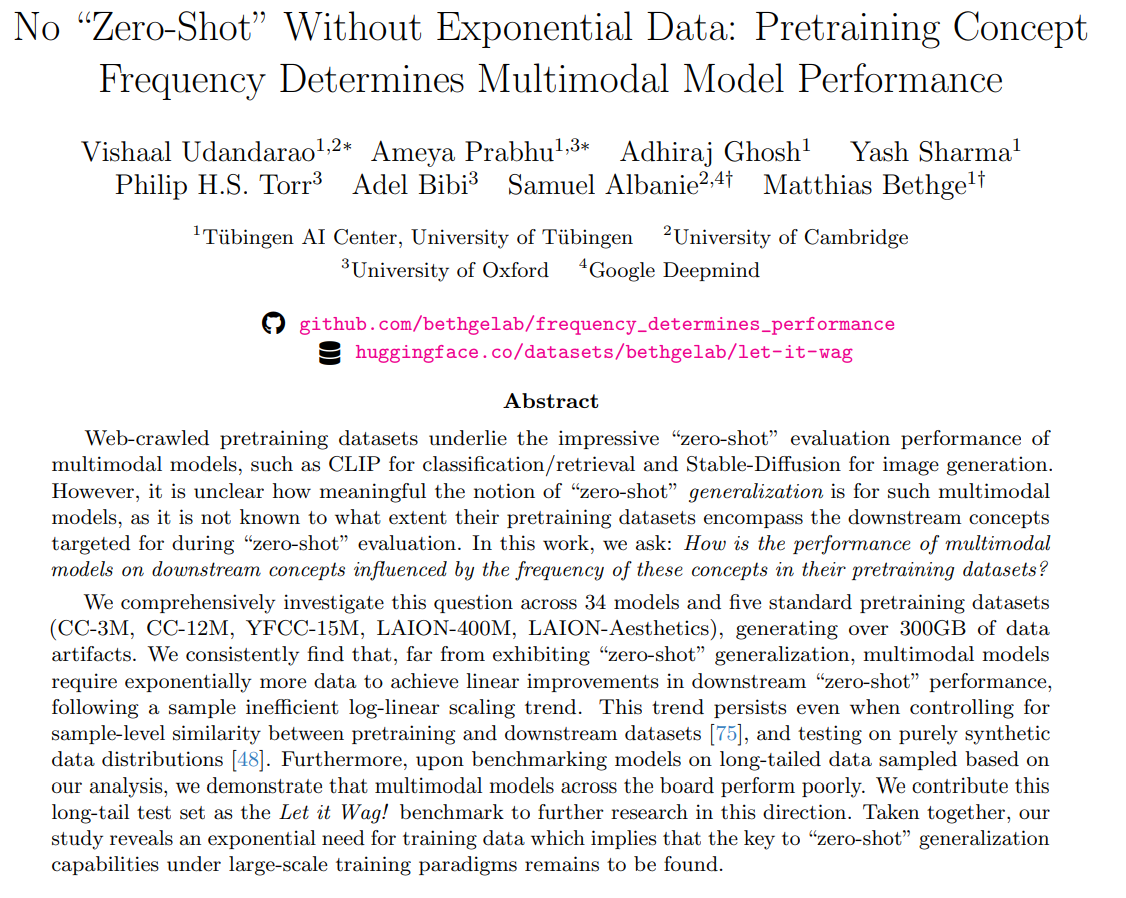

Large language models in particular, such as OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Google DeepMind’s Gemini, have an astonishing ability to generalize. “The magic is not that the model can learn math problems in English and then generalize to new math problems in English,” says Barak, “but that the model can learn math problems in English, then see some French literature, and from that generalize to solving math problems in French. That’s something beyond what statistics can tell you about.”

When Zhou started studying AI a few years ago, she was struck by the way her teachers focused on the how but not the why. “It was like, here is how you train these models and then here’s the result,” she says. “But it wasn’t clear why this process leads to models that are capable of doing these amazing things.” She wanted to know more, but she was told there weren’t good answers: “My assumption was that scientists know what they’re doing. Like, they’d get the theories and then they’d build the models. That wasn’t the case at all.”

The rapid advances in deep learning over the last 10-plus years came more from trial and error than from understanding. Researchers copied what worked for others and tacked on innovations of their own. There are now many different ingredients that can be added to models and a growing cookbook filled with recipes for using them. “People try this thing, that thing, all these tricks,” says Belkin. “Some are important. Some are probably not.”

“It works, which is amazing. Our minds are blown by how powerful these things are,” he says. And yet for all their success, the recipes are more alchemy than chemistry: “We figured out certain incantations at midnight after mixing up some ingredients,” he says.

Overfitting

The problem is that AI in the era of large language models appears to defy textbook statistics. The most powerful models today are vast, with up to a trillion parameters (the values in a model that get adjusted during training). But statistics says that as models get bigger, they should first improve in performance but then get worse. This is because of something called overfitting.

When a model gets trained on a data set, it tries to fit that data to a pattern. Picture a bunch of data points plotted on a chart. A pattern that fits the data can be represented on that chart as a line running through the points. The process of training a model can be thought of as getting it to find a line that fits the training data (the dots already on the chart) but also fits new data (new dots).

A straight line is one pattern, but it probably won’t be too accurate, missing some of the dots. A wiggly line that connects every dot will get full marks on the training data, but won’t generalize. When that happens, a model is said to overfit its data.

An exclusive conversation with Ilya Sutskever on his fears for the future of AI and why they’ve made him change the focus of his life’s work.

According to classical statistics, the bigger a model gets, the more prone it is to overfitting. That’s because with more parameters to play with, it’s easier for a model to hit on wiggly lines that connect every dot. This suggests there’s a sweet spot between under- and overfitting that a model must find if it is to generalize. And yet that’s not what we see with big models. The best-known example of this is a phenomenon known as double descent.

The performance of a model is often represented in terms of the number of errors it makes: as performance goes up, error rate goes down (or descends). For decades, it was believed that error rate went down and then up as models got bigger: picture a U-shaped curve with the sweet spot for generalization at the lowest point. But in 2018, Belkin and his colleagues found that when certain models got bigger, their error rate went down, then up—and then down again (a double descent, or W-shaped curve). In other words, large models would somehow overrun that sweet spot and push through the overfitting problem, getting even better as they got bigger.

A year later, Barak coauthored a paper showing that the

double-descent phenomenon was more common than many thought. It happens not just when models get bigger but also in models with large amounts of training data or models that are trained for longer. This behavior, dubbed benign overfitting, is still not fully understood. It raises basic questions about how models should be trained to get the most out of them.

Researchers have sketched out versions of what they think is going on. Belkin believes there’s a kind of Occam’s razor effect in play: the simplest pattern that fits the data—the smoothest curve between the dots—is often the one that generalizes best. The reason bigger models keep improving longer than it seems they should could be that bigger models are more likely to hit upon that just-so curve than smaller ones: more parameters means more possible curves to try out after ditching the wiggliest.

“Our theory seemed to explain the basics of why it worked,” says Belkin. “And then people made models that could speak 100 languages and it was like, okay, we understand nothing at all.” He laughs: “It turned out we weren’t even scratching the surface.”

For Belkin, large language models are a whole new mystery. These models are based on transformers, a type of neural network that is good at processing sequences of data, like words in sentences.

There’s a lot of complexity inside transformers, says Belkin. But he thinks at heart they do more or less the same thing as a much better understood statistical construct called a Markov chain, which predicts the next item in a sequence based on what’s come before. But that isn’t enough to explain everything that large language models can do. “This is something that, until recently, we thought should not work,” says Belkin. “That means that something was fundamentally missing. It identifies a gap in our understanding of the world.”

Belkin goes further. He thinks there could be a hidden mathematical pattern in language that large language models somehow come to exploit: “Pure speculation but why not?”

“The fact that these things model language is probably one of the biggest discoveries in history,” he says. “That you can learn language by just predicting the next word with a Markov chain—that’s just shocking to me.”