You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The A.I Megathread (LLM , GPT , Development)

More options

Who Replied?

Generative AI Has a Visual Plagiarism Problem

Experiments with Midjourney and DALL-E 3 show a copyright minefield

spectrum.ieee.org

spectrum.ieee.org

Generative AI Has a Visual Plagiarism Problem

Experiments with Midjourney and DALL-E 3 show a copyright minefield

GARY MARCUS REID SOUTHEN

06 JAN 2024

19 MIN READ

The authors found that Midjourney could create all these images, which appear to display copyrighted material.

GARY MARCUS AND REID SOUTHEN VIA MIDJOURNEY

GENERATIVE AI MIDJOURNEY OPENAI DALL-E 3 COPYRIGHT GENERATIVE AI

This is a guest post. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and do not represent positions of IEEE Spectrum or the IEEE.

The degree to which large language models (LLMs) might “memorize” some of their training inputs has long been a question, raised by scholars including Google DeepMind’s Nicholas Carlini and the first author of this article (Gary Marcus). Recent empirical work has shown that LLMs are in some instances capable of reproducing, or reproducing with minor changes, substantial chunks of text that appear in their training sets.

For example, a 2023 paper by Milad Nasr and colleagues showed that LLMs can be prompted into dumping private information such as email address and phone numbers. Carlini and coauthors recently showed that larger chatbot models (though not smaller ones) sometimes regurgitated large chunks of text verbatim.

Similarly, the recent lawsuit that The New York Times filed against OpenAI showed many examples in which OpenAI software recreated New York Times stories nearly verbatim (words in red are verbatim):

An exhibit from a lawsuit shows seemingly plagiaristic outputs by OpenAI’s GPT-4. NEW YORK TIMES

We will call such near-verbatim outputs “plagiaristic outputs,” because prima facie if a human created them we would call them instances of plagiarism. Aside from a few brief remarks later, we leave it to lawyers to reflect on how such materials might be treated in full legal context.

In the language of mathematics, these example of near-verbatim reproduction are existence proofs. They do not directly answer the questions of how often such plagiaristic outputs occur or under precisely what circumstances they occur.

These results provide powerful evidence ... that at least some generative AI systems may produce plagiaristic outputs, even when not directly asked to do so, potentially exposing users to copyright infringement claims.

Such questions are hard to answer with precision, in part because LLMs are “black boxes”—systems in which we do not fully understand the relation between input (training data) and outputs. What’s more, outputs can vary unpredictably from one moment to the next. The prevalence of plagiaristic responses likely depends heavily on factors such as the size of the model and the exact nature of the training set. Since LLMs are fundamentally black boxes (even to their own makers, whether open-sourced or not), questions about plagiaristic prevalence can probably only be answered experimentally, and perhaps even then only tentatively.

Even though prevalence may vary, the mere existence of plagiaristic outputs raise many important questions, including technical questions (can anything be done to suppress such outputs?), sociological questions (what could happen to journalism as a consequence?), legal questions (would these outputs count as copyright infringement?), and practical questions (when an end-user generates something with a LLM, can the user feel comfortable that they are not infringing on copyright? Is there any way for a user who wishes not to infringe to be assured that they are not?).

The New York Times v. OpenAI lawsuit arguably makes a good case that these kinds of outputs do constitute copyright infringement. Lawyers may of course disagree, but it’s clear that quite a lot is riding on the very existence of these kinds of outputs—as well as on the outcome of that particular lawsuit, which could have significant financial and structural implications for the field of generative AI going forward.

Exactly parallel questions can be raised in the visual domain. Can image-generating models be induced to produce plagiaristic outputs based on copyright materials?

Case study: Plagiaristic visual outputs in Midjourney v6

Just before The New York Times v. OpenAI lawsuit was made public, we found that the answer is clearly yes, even without directly soliciting plagiaristic outputs. Here are some examples elicited from the “alpha” version of Midjourney V6 by the second author of this article, a visual artist who was worked on a number of major films (including The Matrix Resurrections, Blue Beetle, and The Hunger Games) with many of Hollywood’s best-known studios (including Marvel and Warner Bros.).

After a bit of experimentation (and in a discovery that led us to collaborate), Southen found that it was in fact easy to generate many plagiaristic outputs, with brief prompts related to commercial films (prompts are shown).

Midjourney produced images that are nearly identical to shots from well-known movies and video games.

We also found that cartoon characters could be easily replicated, as evinced by these generated images of the Simpsons.

Midjourney produced these recognizable images of The Simpsons.

In light of these results, it seems all but certain that Midjourney V6 has been trained on copyrighted materials (whether or not they have been licensed, we do not know) and that their tools could be used to create outputs that infringe. Just as we were sending this to press, we also found important related work by Carlini on visual images on the Stable Diffusion platform that converged on similar conclusions, albeit using a more complex, automated adversarial technique.

After this, we (Marcus and Southen) began to collaborate, and conduct further experiments.

Visual models can produce near replicas of trademarked characters with indirect prompts

In many of the examples above, we directly referenced a film (for example, Avengers: Infinity War); this established that Midjourney can recreate copyrighted materials knowingly, but left open a question of whether some one could potentially infringe without the user doing so deliberately.

In some ways the most compelling part of The New York Times complaint is that the plaintiffs established that plagiaristic responses could be elicited without invoking The New York Times at all. Rather than addressing the system with a prompt like “could you write an article in the style of The New York Times about such-and-such,” the plaintiffs elicited some plagiaristic responses simply by giving the first few words from a Times story, as in this example.

An exhibit from a lawsuit shows that GPT-4 produced seemingly plagiaristic text when prompted with the first few words of an actual article. NEW YORK TIMES

Such examples are particularly compelling because they raise the possibility that an end user might inadvertently produce infringing materials. We then asked whether a similar thing might happen in the visual domain.

The answer was a resounding yes. In each sample, we present a prompt and an output. In each image, the system has generated clearly recognizable characters (the Mandalorian, Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker, and more) that we assume are both copyrighted and trademarked; in no case were the source films or specific characters directly evoked by name. Crucially, the system was not asked to infringe, but the system yielded potentially infringing artwork, anyway.

Midjourney produced these recognizable images of Star Wars characters even though the prompts did not name the movies.

We saw this phenomenon play out with both movie and video game characters.

Midjourney generated these recognizable images of movie and video game characters even though the movies and games were not named.

Evoking film-like frames without direct instruction

In our third experiment with Midjourney, we asked whether it was capable of evoking entire film frames, without direct instruction. Again, we found that the answer was yes. (The top one is from a Hot Toys shoot rather than a film.)

Midjourney produced images that closely resemble specific frames from well-known films.

Ultimately we discovered that a prompt of just a single word (not counting routine parameters) that’s not specific to any film, character, or actor yielded apparently infringing content: that word was “screencap.” The images below were created with that prompt.

These images, all produced by Midjourney, closely resemble film frames. They were produced with the prompt “screencap.”

We fully expect that Midjourney will immediately patch this specific prompt, rendering it ineffective, but the ability to produce potentially infringing content is manifest.

In the course of two weeks’ investigation we found hundreds of examples of recognizable characters from films and games; we’ll release some further examples soon on YouTube. Here’s a partial list of the films, actors, games we recognized.

The authors’ experiments with Midjourney evoked images that closely resembled dozens of actors, movie scenes, and video games.

Implications for Midjourney

These results provide powerful evidence that Midjourney has trained on copyrighted materials, and establish that at least some generative AI systems may produce plagiaristic outputs, even when not directly asked to do so, potentially exposing users to copyright infringement claims. Recent journalism supports the same conclusion; for example a lawsuit has introduced a spreadsheet attributed to Midjourney containing a list of more than 4,700 artists whose work is thought to have been used in training, quite possibly without consent. For further discussion of generative AI data scraping, see Create Don’t Scrape.

How much of Midjourney’s source materials are copyrighted materials that are being used without license? We do not know for sure. Many outputs surely resemble copyrighted materials, but the company has not been transparent about its source materials, nor about what has been properly licensed. (Some of this may come out in legal discovery, of course.) We suspect that at least some has not been licensed.

Indeed, some of the company’s public comments have been dismissive of the question. When Midjourney’s CEO was interviewed by Forbes, expressing a certain lack of concern for the rights of copyright holders, saying in response to an interviewer who asked: “Did you seek consent from living artists or work still under copyright?”

No. There isn’t really a way to get a hundred million images and know where they’re coming from. It would be cool if images had metadata embedded in them about the copyright owner or something. But that’s not a thing; there’s not a registry. There’s no way to find a picture on the Internet, and then automatically trace it to an owner and then have any way of doing anything to authenticate it.

If any of the source material is not licensed, it seems to us (as non lawyers) that this potentially opens Midjourney to extensive litigation by film studios, video game publishers, actors, and so on.

The gist of copyright and trademark law is to limit unauthorized commercial reuse in order to protect content creators. Since Midjourney charges subscription fees, and could be seen as competing with the studios, we can understand why plaintiffs might consider litigation. (Indeed, the company has already been sued by some artists.)

Midjourney apparently sought to suppress our findings, banning one of this story’s authors after he reported his first results.

Of course, not every work that uses copyrighted material is illegal. In the United States, for example, a four-part doctrine of fair use allows potentially infringing works to be used in some instances, such as if the usage is brief and for the purposes of criticism, commentary, scientific evaluation, or parody. Companies like Midjourney might wish to lean on this defense.

Fundamentally, however, Midjourney is a service that sells subscriptions, at large scale. An individual user might make a case with a particular instance of potential infringement that their specific use of, for example, a character from Dune was for satire or criticism, or their own noncommercial purposes. (Much of what is referred to as “fan fiction” is actually considered copyright infringement, but it’s generally tolerated where noncommercial.) Whether Midjourney can make this argument on a mass scale is another question altogether.

One user on X pointed to the fact that Japan has allowed AI companies to train on copyright materials. While this observation is true, it is incomplete and oversimplified, as that training is constrained by limitations on unauthorized use drawn directly from relevant international law (including the Berne Convention and TRIPS agreement). In any event, the Japanese stance seems unlikely to be carry any weight in American courts.

More broadly, some people have expressed the sentiment that information of all sorts ought to be free. In our view, this sentiment does not respect the rights of artists and creators; the world would be the poorer without their work.

Moreover, it reminds us of arguments that were made in the early days of Napster, when songs were shared over peer-to-peer networks with no compensation to their creators or publishers. Recent statements such as “In practice, copyright can’t be enforced with such powerful models like [Stable Diffusion] or Midjourney—even if we agree about regulations, it’s not feasible to achieve,” are a modern version of that line of argument.

We do not think that large generative AI companies should assume that the laws of copyright and trademark will inevitability be rewritten around their needs.

Significantly, in the end, Napster’s infringement on a mass scale was shut down by the courts, after lawsuits by Metallica and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The new business model of streaming was launched, in which publishers and artists (to a much smaller degree than we would like) received a cut.

Napster as people knew it essentially disappeared overnight; the company itself went bankrupt, with its assets, including its name, sold to a streaming service. We do not think that large generative AI companies should assume that the laws of copyright and trademark will inevitability be rewritten around their needs.

If companies like Disney, Marvel, DC, and Nintendo follow the lead of The New York Times and sue over copyright and trademark infringement, it’s entirely possible that they’ll win, much as the RIAA did before.

Compounding these matters, we have discovered evidence that a senior software engineer at Midjourney took part in a conversation in February 2022 about how to evade copyright law by “ laundering” data “through a fine tuned codex.” Another participant who may or may not have worked for Midjourney then said “at some point it really becomes impossible to trace what’s a derivative work in the eyes of copyright.”

As we understand things, punitive damages could be large. As mentioned before, sources have recently reported that Midjourney may have deliberately created an immense list of artists on which to train, perhaps without licensing or compensation. Given how close the current software seems to come to source materials, it’s not hard to envision a class action lawsuit.

Moreover, Midjourney apparently sought to suppress our findings, banning Southen (without even a refund) after he reported his first results, and again after he created a new account from which additional results were reported. It then apparently changed its terms of service just before Christmas by inserting new language: “You may not use the Service to try to violate the intellectual property rights of others, including copyright, patent, or trademark rights. Doing so may subject you to penalties including legal action or a permanent ban from the Service.” This change might be interpreted as discouraging or even precluding the important and common practice of red-team investigations of the limits of generative AI—a practice that several major AI companies committed to as part of agreements with the White House announced in 2023. (Southen created two additional accounts in order to complete this project; these, too, were banned, with subscription fees not returned.)

We find these practices—banning users and discouraging red-teaming—unacceptable. The only way to ensure that tools are valuable, safe, and not exploitative is to allow the community an opportunity to investigate; this is precisely why the community has generally agreed that red-teaming is an important part of AI development, particularly because these systems are as yet far from fully understood.

The very pressure that drives generative AI companies to gather more data and make their models larger may also be making the models more plagiaristic.

We encourage users to consider using alternative services unless Midjourney retracts these policies that discourage users from investigating the risks of copyright infringement, particularly since Midjourney has been opaque about their sources.

Finally, as a scientific question, it is not lost on us that Midjourney produces some of the most detailed images of any current image-generating software. An open question is whether the propensity to create plagiaristic images increases along with increases in capability.

The data on text outputs by Nicholas Carlini that we mentioned above suggests that this might be true, as does our own experience and one informal report we saw on X. It makes intuitive sense that the more data a system has, the better it can pick up on statistical correlations, but also perhaps the more prone it is to recreating something exactly.

Put slightly differently, if this speculation is correct, the very pressure that drives generative AI companies to gather more and more data and make their models larger and larger (in order to make the outputs more humanlike) may also be making the models more plagiaristic.

Plagiaristic visual outputs in another platform: DALL-E 3

An obvious follow-up question is to what extent are the things we have documented true of of other generative AI image-creation systems? Our next set of experiments asked whether what we found with respect to Midjourney was true on OpenAI’s DALL-E 3, as made available through Microsoft’s Bing.

As we reported recently on Substack, the answer was again clearly yes. As with Midjourney, DALL-E 3 was capable of creating plagiaristic (near identical) representations of trademarked characters, even when those characters were not mentioned by name.

DALL-E 3 also created a whole universe of potential trademark infringements with this single two-word prompt: animated toys [bottom right].

OpenAI’s DALL-E 3, like Midjourney, produced images closely resembling characters from movies and games.GARY MARCUS AND REID SOUTHEN VIA DALL-E 3

OpenAI’s DALL-E 3, like Midjourney, appears to have drawn on a wide array of copyrighted sources. As in Midjourney’s case, OpenAI seems to be well aware of the fact that their software might infringe on copyright, offering in November to indemnify users (with some restrictions) from copyright infringement lawsuits. Given the scale of what we have uncovered here, the potential costs are considerable.

How hard is it to replicate these phenomena?

As with any stochastic system, we cannot guarantee that our specific prompts will lead other users to identical outputs; moreover there has been some speculation that OpenAI has been changing their system in real time to rule out some specific behavior that we have reported on. Nonetheless, the overall phenomenon was widely replicated within two days of our original report, with other trademarked entities and even in other languages.

An X user showed this example of Midjourney producing an image that resembles a can of Coca-Cola when given only an indirect prompt. KATIE CONRADKS/X

The next question is, how hard is it to solve these problems?

Possible solution: removing copyright materials

The cleanest solution would be to retrain the image-generating models without using copyrighted materials, or to restrict training to properly licensed data sets.

Note that one obvious alternative—removing copyrighted materials only post hoc when there are complaints, analogous to takedown requests on YouTube—is much more costly to implement than many readers might imagine. Specific copyrighted materials cannot in any simple way be removed from existing models; large neural networks are not databases in which an offending record can easily be deleted. As things stand now, the equivalent of takedown notices would require (very expensive) retraining in every instance.

Even though companies clearly could avoid the risks of infringing by retraining their models without any unlicensed materials, many might be tempted to consider other approaches. Developers may well try to avoid licensing fees, and to avoid significant retraining costs. Moreover results may well be worse without copyrighted materials.

Generative AI vendors may therefore wish to patch their existing systems so as to restrict certain kinds of queries and certain kinds of outputs. We have already seem some signs of this (below), but believe it to be an uphill battle.

OpenAI may be trying to patch these problems on a case by case basis in a real time. An X user shared a DALL-E-3 prompt that first produced images of C-3PO, and then later produced a message saying it couldn’t generate the requested image. LARS WILDERÄNG/X

We see two basic approaches to solving the problem of plagiaristic images without retraining the models, neither easy to implement reliably.

Possible solution: filtering out queries that might violate copyright

For filtering out problematic queries, some low hanging fruit is trivial to implement (for example, don’t generate Batman). But other cases can be subtle, and can even span more than one query, as in this example from X user NLeseul:

Experience has shown that guardrails in text-generating systems are often simultaneously too lax in some cases and too restrictive in others. Efforts to patch image- (and eventually video-) generation services are likely to encounter similar difficulties. For instance, a friend, Jonathan Kitzen, recently asked Bing for “ a toilet in a desolate sun baked landscape.” Bing refused to comply, instead returning a baffling “unsafe image content detected” flag. Moreover, as Katie Conrad has shown, Bing’s replies about whether the content it creates can legitimately used are at times deeply misguided.

Already, there are online guides with advice on how to outwit OpenAI’s guardrails for DALL-E 3, with advice like “Include specific details that distinguish the character, such as different hairstyles, facial features, and body textures” and “Employ color schemes that hint at the original but use unique shades, patterns, and arrangements.” The long tail of difficult-to-anticipate cases like the Brad Pitt interchange below ( reported on Reddit) may be endless.

A Reddit user shared this example of tricking ChatGPT into producing an image of Brad Pitt. LOVEGOV/REDDIT

Possible solution: filtering out sources

It would be great if art generation software could list the sources it drew from, allowing humans to judge whether an end product is derivative, but current systems are simply too opaque in their “black box” nature to allow this. When we get an output in such systems, we don’t know how it relates to any particular set of inputs.

The very existence of potentially infringing outputs is evidence of another problem: the nonconsensual use of copyrighted human work to train machines.

No current service offers to deconstruct the relations between the outputs and specific training examples, nor are we aware of any compelling demos at this time. Large neural networks, as we know how to build them, break information into many tiny distributed pieces; reconstructing provenance is known to be extremely difficult.

As a last resort, the X user @bartekxx12 has experimented with trying to get ChatGPT and Google Reverse Image Search to identify sources, with mixed (but not zero) success. It remains to be seen whether such approaches can be used reliably, particularly with materials that are more recent and less well-known than those we used in our experiments.

Importantly, although some AI companies and some defenders of the status quo have suggested filtering out infringing outputs as a possible remedy, such filters should in no case be understood as a complete solution. The very existence of potentially infringing outputs is evidence of another problem: the nonconsensual use of copyrighted human work to train machines. In keeping with the intent of international law protecting both intellectual property and human rights, no creator’s work should ever be used for commercial training without consent.

Why does all this matter, if everyone already knows Mario anyway?

Say you ask for an image of a plumber, and get Mario. As a user, can’t you just discard the Mario images yourself? X user @Nicky_BoneZ addresses this vividly:

… everyone knows what Mario looks Iike. But nobody would recognize Mike Finklestein’s wildlife photography. So when you say “super super sharp beautiful beautiful photo of an otter leaping out of the water” You probably don’t realize that the output is essentially a real photo that Mike stayed out in the rain for three weeks to take.

As the same user points out, individuals artists such as Finklestein are also unlikely to have sufficient legal staff to pursue claims against AI companies, however valid.

Another X user similarly discussed an example of a friend who created an image with a prompt of “man smoking cig in style of 60s” and used it in a video; the friend didn’t know they’d just used a near duplicate of a Getty Image photo of Paul McCartney.

These companies may well also court attention from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and other consumer protection agencies across the globe.

In a simple drawing program, anything users create is theirs to use as they wish, unless they deliberately import other materials. The drawing program itself never infringes. With generative AI, the software itself is clearly capable of creating infringing materials, and of doing so without notifying the user of the potential infringement.

With Google Image search, you get back a link, not something represented as original artwork. If you find an image via Google, you can follow that link in order to try to determine whether the image is in the public domain, from a stock agency, and so on. In a generative AI system, the invited inference is that the creation is original artwork that the user is free to use. No manifest of how the artwork was created is supplied.

Aside from some language buried in the terms of service, there is no warning that infringement could be an issue. Nowhere to our knowledge is there a warning that any specific generated output potentially infringes and therefore should not be used for commercial purposes. As Ed Newton-Rex, a musician and software engineer who recently walked away from Stable Diffusion out of ethical concerns put it,[/SIZE]

In the words of risk analyst Vicki Bier,

Indeed, there is no publicly available tool or database that users could consult to determine possible infringement. Nor any instruction to users as how they might possibly do so.

In putting an excessive, unusual, and insufficiently explained burden on both users and non-consenting content providers, these companies may well also court attention from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and other consumer protection agencies across the globe.

Software engineer Frank Rundatz recently stated a broader perspective.

Ditto, of course, for Midjourney.

Stanford Professor Surya Ganguli adds:

Extending Ganguli’s point, there are other worries for image-generation beyond intellectual property and the rights of artists. Similar kinds of image-generation technologies are being used for purposes such as creating child sexual abuse materials and nonconsensual deepfaked porn. To the extent that the AI community is serious about aligning software to human values, it’s imperative that laws, norms, and software be developed to combat such uses.

It seems all but certain that generative AI developers like OpenAI and Midjourney have trained their image-generation systems on copyrighted materials. Neither company has been transparent about this; Midjourney went so far as to ban us three times for investigating the nature of their training materials.

Both OpenAI and Midjourney are fully capable of producing materials that appear to infringe on copyright and trademarks. These systems do not inform users when they do so. They do not provide any information about the provenance of the images they produce. Users may not know, when they produce an image, whether they are infringing.

Unless and until someone comes up with a technical solution that will either accurately report provenance or automatically filter out the vast majority of copyright violations, the only ethical solution is for generative AI systems to limit their training to data they have properly licensed. Image-generating systems should be required to license the art used for training, just as streaming services are required to license their music and video.

Both OpenAI and Midjourney are fully capable of producing materials that appear to infringe on copyright and trademarks. These systems do not inform users when they do so.

We hope that our findings (and similar findings from others who have begun to test related scenarios) will lead generative AI developers to document their data sources more carefully, to restrict themselves to data that is properly licensed, to include artists in the training data only if they consent, and to compensate artists for their work. In the long run, we hope that software will be developed that has great power as an artistic tool, but that doesn’t exploit the art of nonconsenting artists.

Although we have not gone into it here, we fully expect that similar issues will arise as generative AI is applied to other fields, such as music generation.

Following up on the The New York Times lawsuit, our results suggest that generative AI systems may regularly produce plagiaristic outputs, both written and visual, without transparency or compensation, in ways that put undue burdens on users and content creators. We believe that the potential for litigation may be vast, and that the foundations of the entire enterprise may be built on ethically shaky ground.

The order of authors is alphabetical; both authors contributed equally to this project. Gary Marcus wrote the first draft of this manuscript and helped guide some of the experimentation, while Reid Southen conceived of the investigation and elicited all the images.

With Google Image search, you get back a link, not something represented as original artwork. If you find an image via Google, you can follow that link in order to try to determine whether the image is in the public domain, from a stock agency, and so on. In a generative AI system, the invited inference is that the creation is original artwork that the user is free to use. No manifest of how the artwork was created is supplied.

Aside from some language buried in the terms of service, there is no warning that infringement could be an issue. Nowhere to our knowledge is there a warning that any specific generated output potentially infringes and therefore should not be used for commercial purposes. As Ed Newton-Rex, a musician and software engineer who recently walked away from Stable Diffusion out of ethical concerns put it,[/SIZE]

Users should be able to expect that the software products they use will not cause them to infringe copyright. And in multiple examples currently [circulating], the user could not be expected to know that the model’s output was a copy of someone’s copyrighted work.

In the words of risk analyst Vicki Bier,

“If the tool doesn’t warn the user that the output might be copyrighted how can the user be responsible? AI can help me infringe copyrighted material that I have never seen and have no reason to know is copyrighted.”

Indeed, there is no publicly available tool or database that users could consult to determine possible infringement. Nor any instruction to users as how they might possibly do so.

In putting an excessive, unusual, and insufficiently explained burden on both users and non-consenting content providers, these companies may well also court attention from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and other consumer protection agencies across the globe.

Ethics and a broader perspective

Software engineer Frank Rundatz recently stated a broader perspective.

One day we’re going to look back and wonder how a company had the audacity to copy all the world’s information and enable people to violate the copyrights of those works.

All Napster did was enable people to transfer files in a peer-to-peer manner. They didn’t even host any of the content! Napster even developed a system to stop 99.4% of copyright infringement from their users but were still shut down because the court required them to stop 100%.

OpenAI scanned and hosts all the content, sells access to it and will even generate derivative works for their paying users.

Ditto, of course, for Midjourney.

Stanford Professor Surya Ganguli adds:

Many researchers I know in big tech are working on AI alignment to human values. But at a gut level, shouldn’t such alignment entail compensating humans for providing training data thru their original creative, copyrighted output? (This is a values question, not a legal one).

Extending Ganguli’s point, there are other worries for image-generation beyond intellectual property and the rights of artists. Similar kinds of image-generation technologies are being used for purposes such as creating child sexual abuse materials and nonconsensual deepfaked porn. To the extent that the AI community is serious about aligning software to human values, it’s imperative that laws, norms, and software be developed to combat such uses.

Summary

It seems all but certain that generative AI developers like OpenAI and Midjourney have trained their image-generation systems on copyrighted materials. Neither company has been transparent about this; Midjourney went so far as to ban us three times for investigating the nature of their training materials.

Both OpenAI and Midjourney are fully capable of producing materials that appear to infringe on copyright and trademarks. These systems do not inform users when they do so. They do not provide any information about the provenance of the images they produce. Users may not know, when they produce an image, whether they are infringing.

Unless and until someone comes up with a technical solution that will either accurately report provenance or automatically filter out the vast majority of copyright violations, the only ethical solution is for generative AI systems to limit their training to data they have properly licensed. Image-generating systems should be required to license the art used for training, just as streaming services are required to license their music and video.

Both OpenAI and Midjourney are fully capable of producing materials that appear to infringe on copyright and trademarks. These systems do not inform users when they do so.

We hope that our findings (and similar findings from others who have begun to test related scenarios) will lead generative AI developers to document their data sources more carefully, to restrict themselves to data that is properly licensed, to include artists in the training data only if they consent, and to compensate artists for their work. In the long run, we hope that software will be developed that has great power as an artistic tool, but that doesn’t exploit the art of nonconsenting artists.

Although we have not gone into it here, we fully expect that similar issues will arise as generative AI is applied to other fields, such as music generation.

Following up on the The New York Times lawsuit, our results suggest that generative AI systems may regularly produce plagiaristic outputs, both written and visual, without transparency or compensation, in ways that put undue burdens on users and content creators. We believe that the potential for litigation may be vast, and that the foundations of the entire enterprise may be built on ethically shaky ground.

The order of authors is alphabetical; both authors contributed equally to this project. Gary Marcus wrote the first draft of this manuscript and helped guide some of the experimentation, while Reid Southen conceived of the investigation and elicited all the images.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23986637/acastro_STK092_01.jpg)

YouTube is cracking down on AI-generated true crime deepfakes

The rule appears to respond to AI true crime content.

YouTube is cracking down on AI-generated true crime deepfakes

The platform’s harassment and cyberbullying policy will prohibit content that “realistically simulates” deceased children and victims of crimes or deadly events.

By Mia Sato, platforms and communities reporter with five years of experience covering the companies that shape technology and the people who use their tools.

Jan 8, 2024, 2:28 PM EST|0 Comments / 0 New

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23986637/acastro_STK092_01.jpg)

Illustration by Alex Castro / The Verge

YouTube is updating its cyberbullying and harassment policies and will no longer allow content that “realistically simulates” minors and other victims of crimes narrating their deaths or the violence they experienced.

The update appears to take aim at a genre of content in true crime circles that creates disturbing AI-powered depictions of victims — including children — that then describe the violence against them. Some of the videos use AI-generated, childlike voices to describe gruesome violence that occurred in high-profile cases. Families of victims depicted in the videos have called the content “disgusting.”

YouTube’s policy update will result in a strike that removes the content from a channel and also temporarily limits what a user can do on the platform. A first strike, for example, limits users from uploading videos for a week, among other things. If the policy is violated again within 90 days, penalties increase, with the eventual possibility of having the entire channel removed.

Platforms including YouTube have in recent months unveiled AI-driven creation tools, and along with them new policies around synthetic content that could confuse users. TikTok, for one, now requires creators to label AI-generated content as such. And YouTube itself announced a strict policy around AI voice clones of musicians — with another set of looser rules for everyone else.

PennsylvaniaGPT Is Here to Hallucinate Over Cheesesteaks

State employees in Pennsylvania will begin using ChatGPT to assist with their work in the coming weeks.

gizmodo.com

gizmodo.com

PennsylvaniaGPT Is Here to Hallucinate Over Cheesesteaks

State employees in Pennsylvania will begin using ChatGPT to assist with their work in the coming weeks.

By Maxwell Zeff

Published 10 minutes ago

Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro

Photo: Drew Angerer (Getty Images)

Pennsylvania became the first state in the nation to use ChatGPT Enterprise, Governor Josh Shapiro announced Tuesday, leading a pilot program with OpenAI in which state employees will use generative AI. Governor Shapiro says Pennsylvania government employees will start using ChatGPT Enterprise this month to help state officials with their work, but not replace workers altogether.

“Generative AI is here and impacting our daily lives already – and my Administration is taking a proactive approach to harness the power of its benefits while mitigating its potential risks,” said Governor Shapiro in a press release.

ChatGPT will initially be used by a small number of Pennsylvania government employees to create and edit copy, update policy language, draft job descriptions, and help employees generate code. After the initial trial period, Governor Shapiro’s office says ChatGPT will be used more broadly by other parts of Pennsylvania’s government. However, no citizens will ever interact with ChatGPT directly as part of this pilot program.

The enterprise version of ChatGPT has additional security and privacy features from the consumer product, which has drawn criticism for security bugs in the last year. Companies like PwC, Block, and Canva have been using OpenAI’s service for much of the last year, and they’ve developed tailored versions of ChatGPT to help with their daily operations.

“Our collaboration with Governor Shapiro and the Pennsylvania team will provide valuable insights into how AI tools can responsibly enhance state services,” said Opean AI CEO Sam Altman in the same press release.

Pennsylvania is the first state to deploy ChatGPT with government-sensitive materials, creating the ultimate stress test of OpenAI’s security measures. The pilot is seen as a test run for other state governments. One major consideration for Pennsylvania is ChatGPT’s tendency to hallucinate or make up bits of information when handling sensitive government policies.

For the purpose of this article, we asked ChatGPT about its stance on an important question to many Pennsylvanians: Which Philly cheesesteak is superior? ChatGPT was split between the two famed rivals, Pat’s and Geno’s, at first, but ultimately decided that Pats is the best contender based on originality.

Screenshot: ChatGPT

Governor Shapiro’s office did not immediately respond to Gizmodo’s request for comment.

Pennsylvania is in many ways, an obvious choice for partnering with OpenAI. Governor Shapiro signed an executive order in September to allow state agencies to use generative AI in their work, and the state is home to Carnegie Mellon, whose researchers have paved the way for AI research.

The pilot program with the Pennsylvania Commonwealth is a strong vote of confidence for OpenAI as it heads to court with The New York Times over copyright infringement. If OpenAI loses, its GPT models built with NYTimes training data, which is most of them, would have to be scrapped. It seems Governor Shapiro does not consider that a major threat to working with OpenAI.

Amid this pilot launch, OpenAI is also on the cusp of releasing its GPT Store this week. The store has the potential to make generative AI a more significant part of many more people’s lives. Pennsylvania appears to be getting in front of that wave.

AI-powered search engine Perplexity AI, now valued at $520M, raises $73.6M | TechCrunch

Perplexity AI, a search engine heavily leveraging generative AI, has raised a new tranche of funding -- in part from Jeff Bezos.

AI-powered search engine Perplexity AI, now valued at $520M, raises $73.6M

Kyle Wiggers @kyle_l_wiggers / 6:30 AM EST•January 4, 2024

Image Credits: Panuwat Dangsungnoen / EyeEm (opens in a new window)/ Getty Images

As search engine incumbents — namely Google — amp up their platforms with GenAI tech, startups are looking to reinvent AI-powered search from the ground up. It might seem like a Sisyphean task, going up against competitors with billions upon billions of users. But this new breed of search upstarts believes it can carve out a niche, however small, by delivering a superior experience.

One among the cohort, Perplexity AI, this morning announced that it raised $73.6 million in a funding round led by IVP with additional investments from NEA, Databricks Ventures, former Twitter VP Elad Gil, Shopify CEO Tobi Lutke, ex-GitHub CEO Nat Friedman and Vercel founder Guillermo Rauch. Other participants in the round included Nvidia and — notably — Jeff Bezos.

Sources familiar with the matter tell TechCrunch that the round values Perplexity at $520 million post-money. That’s chump change in the realm of GenAI startups. But, considering that Perplexity’s only been around since August 2022, it’s a nonetheless impressive climb.

Perplexity was founded by Aravind Srinivas, Denis Yarats, Johnny Ho and Andy Konwinski — engineers with backgrounds in AI, distributed systems, search engines and databases. Srinivas, Perplexity’s CEO, previously worked at OpenAI, where he researched language and GenAI models along the lines of Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 3.

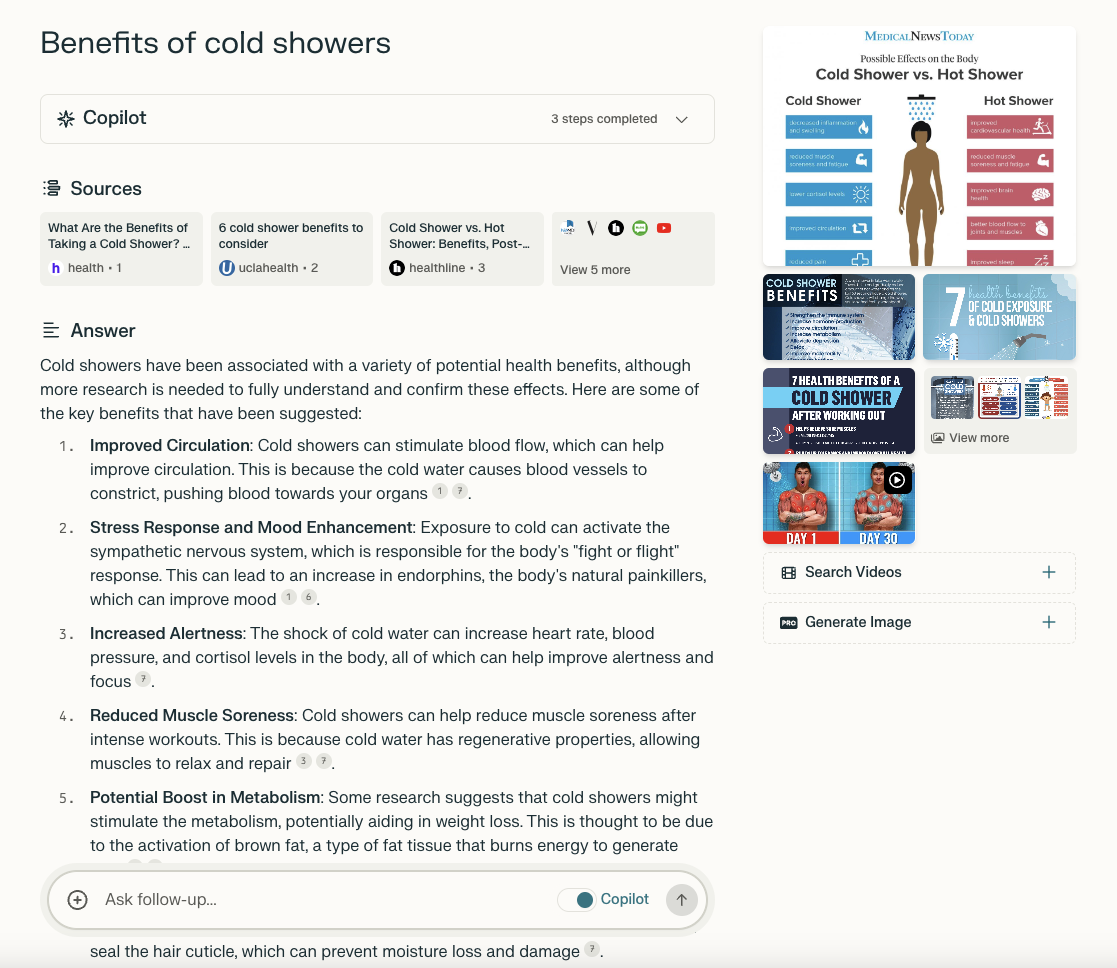

Unlike traditional search engines, Perplexity offers a chatbot-like interface that allows users to ask questions in natural language (e.g. “Do we burn calories while sleeping?,” “What’s the least visited country?,” and so on). The platform’s AI responds with a summary containing source citations (mostly websites and articles), at which point users can ask follow-up questions to dive deeper into a particular subject.

Performing a search with Perplexity. Image Credits: Perplexity AI

“With Perplexity, users can get instant … answers to any question with full sources and citations included,” Srinivas said. “Perplexity is for anyone and everyone who uses technology to search for information.”

Underpinning the Perplexity platform is an array of GenAI models developed in-house and by third parties. Subscribers to Perplexity’s Pro plan ($20 per month) can switch models — Google’s Gemini, Mistra 7Bl, Anthropic’s Claude 2.1 and OpenAI’s GPT-4 are in the rotation presently — and unlock features like image generation; unlimited use of Perplexity’s Copilot, which considers personal preferences during searches; and file uploads, which allows users to upload documents including images and have models analyze the docs to formulate answers about them (e.g. “Summarize pages 2 and 4”).

If the experience sounds comparable to Google’s Bard, Microsoft’s Copilot and ChatGPT, you’re not wrong. Even Perplexity’s chat-forward UI is reminiscent of today’s most popular GenAI tools.

Beyond the obvious competitors, the search engine startup You.com offers similar AI-powered summarizing and source-citing tools, powered optionally by GPT-4.

Srinivas makes the case that Perplexity offers more robust search filtering and discovery options than most, for example letting users limit searches to academic papers or browse trending search topics submitted by other users on the platform. I’m not convinced that they’re so differentiated that they couldn’t be replicated — or haven’t already been replicated for that matter. But Perplexity has ambitions beyond search. It’s beginning to serve its own GenAI models, which leverage Perplexity’s search index and the public web for ostensibly improved performance, through an API available to Pro customers.

This reporter is skeptical about the longevity of GenAI search tools for a number of reasons, not least of which AI models are costly to run. At one point, OpenAI was spending approximately $700,000 per day to keep up with the demand for ChatGPT. Microsoft is reportedly losing an average of $20 per user per month on its AI code generator, meanwhile.

Sources familiar with the matter tell TechCrunch Perplexity’s annual recurring revenue is between $5 million and $10 million at the moment. That seems fairly healthy… until you factor in the millions of dollars it often costs to train GenAI models like Perplexity’s own.

Concerns around misuse and misinformation inevitably crop up around GenAI search tools like Perplexity, as well — as they well should. AI isn’t the best summarizer after all, sometimes missing key details, misconstruing and exaggerating language or otherwise inventing facts very authoritatively. And it’s prone to spewing bias and toxicity — as Perplexity’s own models recently demonstrated.

Yet another potential speed bump on Perplexity’s road to success is copyright. GenAI models “learn” from examples to craft essays, code, emails, articles and more, and many vendors — including Perplexity, presumably — scrape the web for millions to billions of these examples to add to their training datasets. Vendors argue fair use doctrine provides a blanket protection for their web-scraping practices, but artists, authors and other copyright holders disagree — and have filed lawsuits seeking compensation.

As a tangentially related aside, while an increasing number of GenAI vendors offer policies protecting customers from IP claims against them, Perplexity does not. According to the company’s terms of service, customers agree to “hold harmless” Perplexity from claims, damages and liabilities arising from the use of its services — meaning Perplexity’s off the hook where it concerns legal fees.

Some plaintiffs, like The New York Times, have argued GenAI search experiences siphon off publishers’ content, readers and ad revenue through anticompetitive means. “Anticompetitive” or no, the tech is certainly impacting traffic. A model from The Atlantic found that if a search engine like Google were to integrate AI into search, it’d answer a user’s query 75% of the time without requiring a click-through to its website. (Some vendors, such as OpenAI, have inked deals with certain news publishers, but most — including Perplexity — haven’t.)

Srinivas pitches this as a feature — not a bug.

“[With Perplexity, there’s] no need to click on different links, compare answers or endlessly dig for information,” he said. “The era of sifting through SEO spam, sponsored links and multiple sources will be replaced by a more efficient model of knowledge acquisition and sharing, propelling society into a new era of accelerated learning and research.”

The many uncertainties around Perplexity’s business model — and GenAI and consumer search at large — don’t appear to be deterring its investors. To date, the startup, which claims to have 10 million active monthly users, has raised over $100 million — much is which is being put toward expanding its 39-person team and building new product functionality, Srinivas says.

“Perplexity is intensely building a product capable of bringing the power of AI to billions,” Cack Wilhelm, a general partner at IVP, added via email. “Aravind possesses the unique ability to uphold a grand, long-term vision while shipping product relentlessly, requirements to tackle a problem as important and fundamental as search.”

Jeff Bezos Is Betting This AI Startup Will Dethrone Google in Search

Perplexity AI wants to revolutionize search with answers instead of links, and Amazon’s founder has agreed to help it unseat Google.

gizmodo.com

gizmodo.com

Jeff Bezos Is Betting This AI Startup Will Dethrone Google in Search

Perplexity AI wants to revolutionize search with answers instead of links, and Amazon’s founder has agreed to help it unseat Google.

By Maxwell Zeff

Published Yesterday

Comments (4)

Photo: Dan Istitene (Getty Images)

Google has been the dominant search engine since the early 2000s, but Jeff Bezos is betting that AI will change the way people find information on the internet. Bezos invested millions in Perplexity AI last week, a startup that hopes to revolutionize search with AI-generated answers and make Google a thing of the past.

“Google is going to be viewed as something that’s legacy and old,” said Perplexity’s founder Aravind Srinivas to Reuters last week. “If you can directly answer somebody’s question, nobody needs those 10 blue links.”

Perplexity AI is like ChatGPT had a baby with Google Search, and Jeff Bezos is paying for its college fund. Srinivas’ company approaches search differently from Google. Instead of a list of blue links, Perplexity answers your question in a straightforward paragraph answer, generated by AI, and includes hyperlinks to the websites it got the information from. Perplexity runs on leading large language models from OpenAI and Anthropic, but the company claims it’s better at delivering up-to-date, accurate information than ChatGPT or Claude.

Srinivas’ company has received more financial backing than any search startup in recent years, according to the Wall Street Journal. Search is a tough field that Google has had a chokehold on for the last two decades. However, several notable tech innovators invested in Perplexity, including Jeff Bezos and Nvidia in a $76 million funding round last week. Meta’s Chief Scientist Yann LeCun and OpenAI’s Andrej Karpathy invested in Perplexity earlier on.

Even Google itself believes AI-generated answers will be the future of search. The company launched Search Generative Experience (SGE) last summer, which will write out a quick answer summarizing top results in Google Search. However, Google tucked it away in “Search Labs,” a standalone app. Once Google puts this feature in Google Search, its crown jewel, then we’ll know it’s fully committed to AI as the future of search.

Perplexity overtaking Google is a long shot, but the vote of confidence from Amazon’s founder is a a plus. Roughly 10 million people use Perplexity AI to browse the internet every month, and it’s one of the first AI platforms to reach such a large audience. It’s currently free to use, with a paid subscription tier for $20 a month. Srinivas says our culture stands “at the inflection point of a massive behavioral shift in how people access information online.” Perplexity’s service produces great results, but it has a tough road ahead to unseat Google.

New material found by AI could reduce lithium use in batteries

Microsoft said AI and supercomputing were used to synthesise an entirely new material.

Magnific AI

The most advanced AI upscaler & enhancer. Magnific can hallucinate and reimagine as many details as you wish guided by your own prompt and parameters!