There needs to be term limits but I don't see a problem with asking an elderly woman with medical conditions to step down. It would prevent a potential 7-2 GOP SCOTUS . You guys need to start living in reality. The GOP is playing to stay in power for decades. Democrats need to do the same as the only way to protect the country. We don't live in normal times anymore. Obama absolutely should've pressured rbg to retire.ah so that's how it works. let the old white woman die in office at 87 and then use that as a reason why a 69 yr old non-white woman should retire because she has diabetes. all supreme court justices should retire so that their party can pick a replacement just in case.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

SCOTUS Watch Thread

- Thread starter Hood Critic

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Hood Critic

The Power Circle

Hood Critic

The Power Circle

1/3

My view of where the Supreme Court lines up on a spectrum of presidential immunity in Trump v. United States:

~ no immunity~

Sotomayor, J.

Jackson, J.

Kagan, J.

Barrett, J.

Roberts, C.J. *key vote*

Kavanaugh, J.

Gorsuch, J.

Thomas, J.

Alito, J.

~ absolute immunity~

2/3

In what scenario is trying to overturn an election you lost an official act?

3/3

Ain't no rules that say a dog can't play basketball. Similarly, ain't no rules that say an attorney can't question the judges. But I'm confident they won't answer the questions.

Somebody should ask Alito what happens under his theory of immunity if Biden has him kidnapped, forges a letter of retirement, disappears him to Guantanamo Bay, and then appoints a new judge in his place. Is Biden immune from prosecution?

To post tweets in this format, more info here: https://www.thecoli.com/threads/tips-and-tricks-for-posting-the-coli-megathread.984734/post-52211196

My view of where the Supreme Court lines up on a spectrum of presidential immunity in Trump v. United States:

~ no immunity~

Sotomayor, J.

Jackson, J.

Kagan, J.

Barrett, J.

Roberts, C.J. *key vote*

Kavanaugh, J.

Gorsuch, J.

Thomas, J.

Alito, J.

~ absolute immunity~

2/3

In what scenario is trying to overturn an election you lost an official act?

3/3

Ain't no rules that say a dog can't play basketball. Similarly, ain't no rules that say an attorney can't question the judges. But I'm confident they won't answer the questions.

Somebody should ask Alito what happens under his theory of immunity if Biden has him kidnapped, forges a letter of retirement, disappears him to Guantanamo Bay, and then appoints a new judge in his place. Is Biden immune from prosecution?

To post tweets in this format, more info here: https://www.thecoli.com/threads/tips-and-tricks-for-posting-the-coli-megathread.984734/post-52211196

Trump immunity fight turns Supreme Court textualists topsy-turvy

“It sure ain’t originalism,” one critic said.

Diana Neary of Minneapolis, joins other protesters demonstrating outside the Supreme Court as the justices hear arguments over whether former President Donald Trump is immune from prosecution in a case charging him with plotting to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, in Washington on April 25, 2024. | J. Scott Applewhite/AP

By JOSH GERSTEIN

04/27/2024 07:00 AM EDT

The Supreme Court’s conservatives often accuse liberals of inventing provisions nowhere to be found in the Constitution. Now, the fingers are pointed in the other direction.

At the attention-grabbing arguments this week over Donald Trump’s claim of sweeping presidential immunity from criminal prosecution, the six-member conservative bloc seemed largely unconcerned by a key flaw in Trump’s theory: Nothing in the Constitution explicitly mentions the concept of presidential immunity.

Trump’s lawyer told the justices that the founders had “in a sense” written immunity into the Constitution because it’s a logical outgrowth of a broadly worded clause about presidential power. But that’s the sort of argument conservative justices have often scoffed at — most notably in the context of abortion rights.

Two years ago, conservatives relied on a strict interpretation of the Constitution’s text and original meaning to overturn the federal right to abortion. But on Thursday, as they debated whether Trump can be prosecuted for his bid to subvert the 2020 election, they seemed content to engage in a free-form balancing exercise where they weighed competing interests and practical consequences.

Some critics said the conservative justices — all of whom purport to adhere to an original understanding of the Constitution — appeared to be on the verge of fashioning a legal protection for former presidents based on the justices’ subjective assessment of what’s best for the country and not derived from the nation’s founding document.

From left to right: Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts hear arguments. | Dana Verkouteren/AP

“The legal approach they seemed to be gravitating toward has no basis in the Constitution, in precedent, or logic,” said Michael Waldman, president and CEO of New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice. “It sure ain’t originalism.”

The two-hour, 40-minute argument session featured a boatload of scary hypotheticals about coups and assassinations, along with predictions about serial, tit-for-tat prosecutions of future presidents, but there was little discussion of the Constitution’s text.

That could come as a surprise to some. Justice Elena Kagan, one of the three liberals now on the court, famously declared in 2015 that conservatives had essentially won the decadeslong battle between those who favored a close fealty to text and original meaning and those who emphasized pragmatism or saw the Constitution as an evolving document.

“I think we are all textualists now,” Kagan told an audience at Harvard Law School then, as she delivered a lecture named for her then-colleague Justice Anontin Scalia, arguably the lead crusader for the text-based approach.

Kagan was perhaps the most insistent Thursday in highlighting the absence of any explicit immunity for presidents in the Constitution.

“The framers did not put an immunity clause into the Constitution. They knew how to. There were immunity clauses in some state constitutions. They knew how to give legislative immunity. They didn’t provide immunity to the president,” said Kagan, an appointee of President Barack Obama. “And, you know, not so surprising. They were reacting against a monarch who claimed to be above the law.”

Arguing for the Justice Department and special counsel Jack Smith, attorney Michael Dreeben emphasized that the court would effectively be announcing judge-made law if it says presidents are entitled to criminal immunity.

“There is no immunity that is in the Constitution, unless this Court creates it,” Dreeben declared. “There certainly is no textual immunity. … I think it would be a sea change to announce a sweeping rule of immunity that no president has had or has needed.”

Of course, the court isn’t writing on a blank slate. The current justices aren’t the ones who essentially made up executive privilege in a 1974 ruling related to the Watergate probe or the president’s immunity from civil suits in a 1983 case brought by an Air Force analyst pushed out of his job. Those cases were mentioned numerous times in Thursday’s arguments.

“Whoever is a textualist is a textualist leavened by precedent,” University of Virginia law professor Saikrishna Prakash said. “To say that everybody’s a textualist … I think suggests to some people the false hope that we all agree about what something means. I mean, we’re all speaking English, but we all disagree on the margins about what to make of someone’s communications.”

Dreeben told the court that the Justice Department supports those earlier rulings on presidential privilege and immunity, even though the Constitution contains no explicit provision addressing either topic.

A prominent Supreme Court critic, Georgia State University law professor Eric Segall, said there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the justices reaching a legal conclusion that lacks direct support in the Constitution. But he said the members of the nation’s highest court should not pretend that, in doing so, they are simply engaged in a mechanistic application of legal text.

“Do I think there should be some kind of constitutional privilege for the President? Yes, I do. But we have to recognize how atextual that is,” Segall said.

Calling someone a “purposivist” or a “consequentialist” might set off a brawl at a Federalist Society gathering, but the raft of hypotheticals offered by both liberal and conservative justices suggested they were intensely focused on both the founders’ purposes in laying out three separate branches of government and the possible consequences of giving or denying Trump his requested immunity.

The conservative justices did not completely ignore textualism in the Trump arguments Thursday. Indeed, the first question asked — from Justice Clarence Thomas — urged Trump lawyer D. John Sauer to “be more precise as to the source of this immunity.”

In response, Sauer pointed to the extraordinarily broad words of the first sentence of Article II of the Constitution. “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America,” it reads. Sauer didn’t read it aloud, perhaps because one can’t find any discussion of immunity there.

Sometimes, the court has found the absence of such language to be of great import.

Writing for five conservative justices in the earth-shaking abortion case two years ago, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Justice Samuel Alito referred to the notion of guaranteed access to abortion as “an asserted right that is nowhere mentioned in the Constitution.”

On Thursday, Sauer did offer one argument for presidential immunity drawn relatively directly from the text of the Constitution: The assertion that the language allowing for criminal conviction of a federal officer after impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate implies that a current or former president can’t be criminally charged until and unless he or she is convicted by the Senate.

No justice of any stripe seemed particularly interested in that contention, although a couple did poke holes in it.

“What if the criminal conduct isn’t discovered until after the president is out of office, so there was no opportunity for impeachment?” Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked.

Sauer appeared to concede that adopting Trump’s approach would mean some presidential misconduct could never be punished.

“We say the framers assumed the risk of under-enforcement by adopting these very structural checks,” the Trump lawyer said.

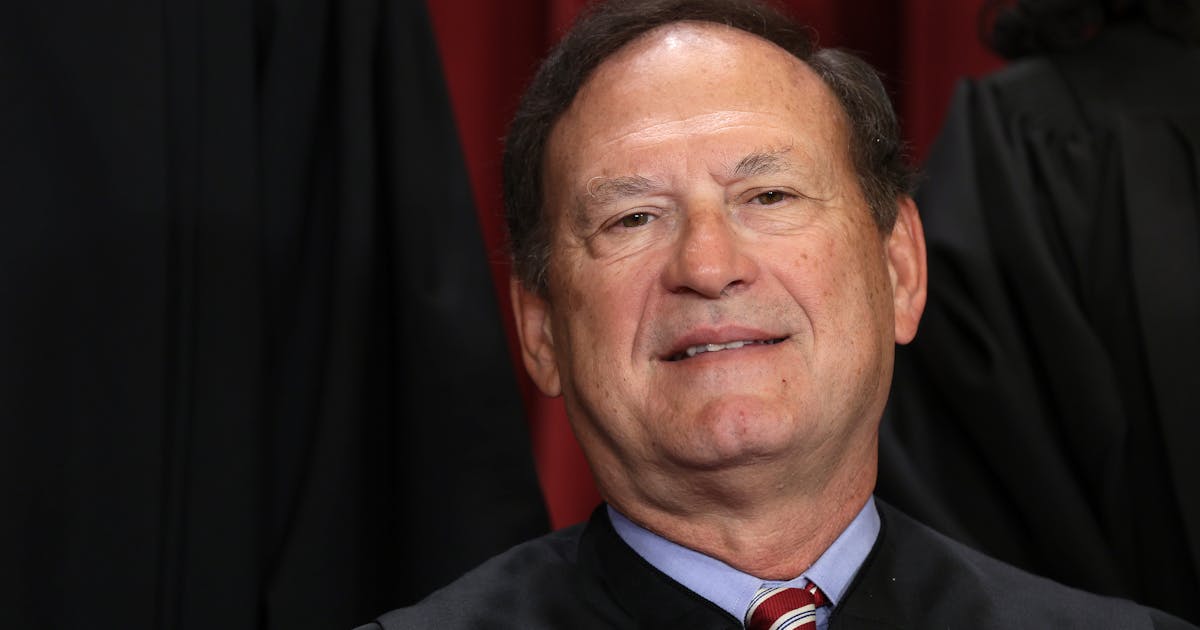

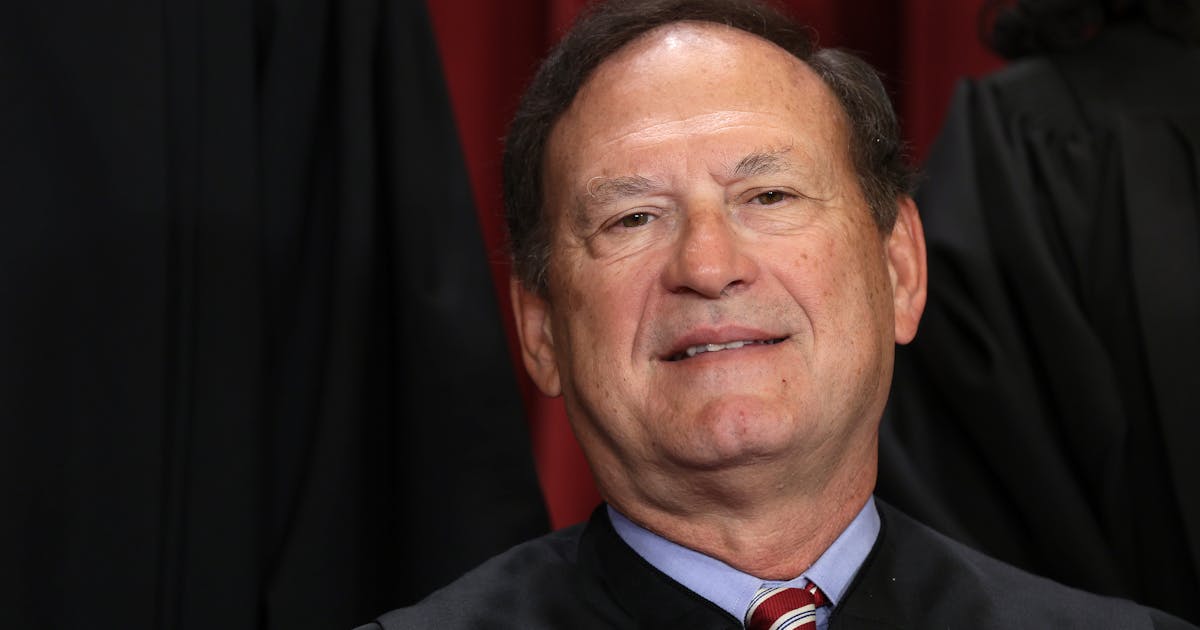

Samuel Alito’s Resentment Goes Full Tilt on a Black Day for the Court

The associate justice’s logic on display at the Trump immunity hearing was beyond belief. He’s at the center of one of the darkest days in Supreme Court history.

Samuel Alito’s Resentment Goes Full Tilt on a Black Day for the Court

The associate justice’s logic on display at the Trump immunity hearing was beyond belief. He’s at the center of one of the darkest days in Supreme Court history.

ALEX WONG/GETTY IMAGES

On the day Donald Trump took office in January 2017, pondering what he might do to the country’s democratic norms and institutions, I wrote these words: “Trump will destroy them, if keeping Trump on top requires it. Or try to. He might not succeed. And that is where we rest our hope—on conservative judges who will choose our institutions over Trump. Mark my words: It will come to this.”

That hope seemed not misplaced back in 2020 and 2021, when a number of liberal and conservative judges, some of the latter appointed by Trump himself, handed Trump 60 or so legal defeats as he attempted to unlawfully overturn the election results. But after Thursday at the Supreme Court? That hope is dead. The conservative judges, or at least most of them, on the highest court in the land are very clearly choosing Trump over our institutions. And none more belligerently than Samuel Alito.

His line of questioning to Michael Dreeben, the attorney arguing the special counsel’s case, was from some perverse Lewis Carroll universe:

Now if an incumbent who loses a very close, hotly contested election knows that a real possibility after leaving office is not that the president is going to be able to go off into a peaceful retirement, but that the president may be criminally prosecuted by a bitter political opponent, will that not lead us into a cycle that destabilizes the functioning of our country as a democracy?

Let’s look to something I’d have thought lawyers and judges took seriously: historical evidence. American democracy has existed for nigh on 250 years, and power has been transferred from a president to his successor a grand total of 40 times (not counting deaths in office). On 11 occasions, a challenger has defeated a sitting incumbent—that is, a situation that creates the potential for some particularly bitter and messy post-election shenanigans.

Now, if Alito’s question really spoke to a malign condition that had hobbled American democracy throughout history and that loomed as a real problem that we had to take very seriously, it would stand to reason that our history suggested that these power transfers had had a wobbly history—that maybe, say, 12 of 40, and four or five of the 11, had been characterized by violence and unusual threats of retribution against the exiting executive.

But what does the record show? It shows, of course, that there is only one case out of the overall 40, and one case out of the more narrowly defined 11, in all of U.S. history where anything abnormal and non-peaceful happened. That, of course, was 2020.

And there was a lot of bad blood in previous transfers of power. You think John Adams loved the idea of handing power to Thomas Jefferson? John Quincy Adams was popping champagne to turn things over to Andrew Jackson? Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison, who traded wins, weren’t bitter in defeat? These people couldn’t stand each other. But they did what custom required—a custom never questioned by anyone until Trump came along.

So in other words: Alito throws all that democratic history out the window and treats Trump as the new normal, assuming that the American future is ineluctably strewn with a series of lawless Trumps. Alas, with respect to the Republican Party, there’s a chance time will prove him right about that (but only a chance; my cynicism about the depths to which this GOP will sink is almost limitless, but even I think that Trump is most likely sui generis in this respect, and that your average Republican, even the neofascist ones like Tom Cotton, should we be cursed with a Cotton presidency someday, would probably yield power peacefully if he lost).

But think about what it says about both where Trump has delivered this country, and about Alito’s assumptions about democracy. On the former point: Have we now reached a place where challenges to election results are going to be the norm? Where an opposition party can be counted on to find some legal technicality on which to prosecute a former president, rather than leaving him or her in peace as we have throughout our history?

This is another twisting of reality. Trump, his defenders would protest, is the one former president who has not been left in peace. Well, that is true, I confess. But maybe there’s a reason for it! Actually, there are two. Trump has not been left in peace because a) it was always obvious he was not retired, and b) he’s the only ex-president who tried to foment a coup against the United States of America and who declassified sensitive national security documents with his beautiful brain.

And on the latter point: When George W. Bush named him to the court in 2005, experts told us—of course—that Alito was conservative, yes, but not an extremist (interestingly, Maryanne Trump Barry, Donald’s sister under whom Alito had worked as a prosecutor, was among those recommending Alito’s nomination). As The New Yorker reported in a 2022 profile, Alito was asked in 2014 to name a character trait that hadn’t served him well. His answer? A tendency to hold his tongue. Well, that problem’s been solved, eh? As writer Margaret Talbot noted of the justice, who ignored Chief Justice John Roberts’s importunings to strike a balance in the Dobbs decision, which he wrote: “He’s holding his tongue no longer. Indeed, Alito now seems to be saying whatever he wants in public, often with a snide pugnaciousness that suggests his past decorum was suppressing considerable resentment.”

And this week, he told us, in essence, that in his view democracy depends on allowing presidents to commit federal crimes, because if ex-presidents were to be prosecuted for such things, the United States would become a banana republic. That’s a Supreme Court justice saying that. And while Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and even Clarence Thomas didn’t go that far Thursday, it was obvious that the court’s conservatives are maneuvering to make sure that the insurrection trial doesn’t see the light of day before the election—in other words, that a sitting president who very clearly wanted Congress to overturn a constitutionally certified election result (about this there is zero dispute) should pay no price for those actions.

When I wrote seven years ago that we rested our hope on conservative judges who will choose our institutions over Trump, trust me, I wasn’t saying I was confident that they would. I was terrified that that day would eventually come. It came yesterday. The conservative jurists chose Trump. It will stand as one of the blackest days in Supreme Court history.

This article first appeared in Fighting Words, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by editor Michael Tomasky. Sign up here.

88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

Samuel Alito’s Resentment Goes Full Tilt on a Black Day for the Court

The associate justice’s logic on display at the Trump immunity hearing was beyond belief. He’s at the center of one of the darkest days in Supreme Court history.newrepublic.com

Samuel Alito’s Resentment Goes Full Tilt on a Black Day for the Court

The associate justice’s logic on display at the Trump immunity hearing was beyond belief. He’s at the center of one of the darkest days in Supreme Court history.

ALEX WONG/GETTY IMAGES

On the day Donald Trump took office in January 2017, pondering what he might do to the country’s democratic norms and institutions, I wrote these words: “Trump will destroy them, if keeping Trump on top requires it. Or try to. He might not succeed. And that is where we rest our hope—on conservative judges who will choose our institutions over Trump. Mark my words: It will come to this.”

That hope seemed not misplaced back in 2020 and 2021, when a number of liberal and conservative judges, some of the latter appointed by Trump himself, handed Trump 60 or so legal defeats as he attempted to unlawfully overturn the election results. But after Thursday at the Supreme Court? That hope is dead. The conservative judges, or at least most of them, on the highest court in the land are very clearly choosing Trump over our institutions. And none more belligerently than Samuel Alito.

His line of questioning to Michael Dreeben, the attorney arguing the special counsel’s case, was from some perverse Lewis Carroll universe:

Let’s look to something I’d have thought lawyers and judges took seriously: historical evidence. American democracy has existed for nigh on 250 years, and power has been transferred from a president to his successor a grand total of 40 times (not counting deaths in office). On 11 occasions, a challenger has defeated a sitting incumbent—that is, a situation that creates the potential for some particularly bitter and messy post-election shenanigans.

Now, if Alito’s question really spoke to a malign condition that had hobbled American democracy throughout history and that loomed as a real problem that we had to take very seriously, it would stand to reason that our history suggested that these power transfers had had a wobbly history—that maybe, say, 12 of 40, and four or five of the 11, had been characterized by violence and unusual threats of retribution against the exiting executive.

But what does the record show? It shows, of course, that there is only one case out of the overall 40, and one case out of the more narrowly defined 11, in all of U.S. history where anything abnormal and non-peaceful happened. That, of course, was 2020.

And there was a lot of bad blood in previous transfers of power. You think John Adams loved the idea of handing power to Thomas Jefferson? John Quincy Adams was popping champagne to turn things over to Andrew Jackson? Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison, who traded wins, weren’t bitter in defeat? These people couldn’t stand each other. But they did what custom required—a custom never questioned by anyone until Trump came along.

So in other words: Alito throws all that democratic history out the window and treats Trump as the new normal, assuming that the American future is ineluctably strewn with a series of lawless Trumps. Alas, with respect to the Republican Party, there’s a chance time will prove him right about that (but only a chance; my cynicism about the depths to which this GOP will sink is almost limitless, but even I think that Trump is most likely sui generis in this respect, and that your average Republican, even the neofascist ones like Tom Cotton, should we be cursed with a Cotton presidency someday, would probably yield power peacefully if he lost).

But think about what it says about both where Trump has delivered this country, and about Alito’s assumptions about democracy. On the former point: Have we now reached a place where challenges to election results are going to be the norm? Where an opposition party can be counted on to find some legal technicality on which to prosecute a former president, rather than leaving him or her in peace as we have throughout our history?

This is another twisting of reality. Trump, his defenders would protest, is the one former president who has not been left in peace. Well, that is true, I confess. But maybe there’s a reason for it! Actually, there are two. Trump has not been left in peace because a) it was always obvious he was not retired, and b) he’s the only ex-president who tried to foment a coup against the United States of America and who declassified sensitive national security documents with his beautiful brain.

And on the latter point: When George W. Bush named him to the court in 2005, experts told us—of course—that Alito was conservative, yes, but not an extremist (interestingly, Maryanne Trump Barry, Donald’s sister under whom Alito had worked as a prosecutor, was among those recommending Alito’s nomination). As The New Yorker reported in a 2022 profile, Alito was asked in 2014 to name a character trait that hadn’t served him well. His answer? A tendency to hold his tongue. Well, that problem’s been solved, eh? As writer Margaret Talbot noted of the justice, who ignored Chief Justice John Roberts’s importunings to strike a balance in the Dobbs decision, which he wrote: “He’s holding his tongue no longer. Indeed, Alito now seems to be saying whatever he wants in public, often with a snide pugnaciousness that suggests his past decorum was suppressing considerable resentment.”

And this week, he told us, in essence, that in his view democracy depends on allowing presidents to commit federal crimes, because if ex-presidents were to be prosecuted for such things, the United States would become a banana republic. That’s a Supreme Court justice saying that. And while Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and even Clarence Thomas didn’t go that far Thursday, it was obvious that the court’s conservatives are maneuvering to make sure that the insurrection trial doesn’t see the light of day before the election—in other words, that a sitting president who very clearly wanted Congress to overturn a constitutionally certified election result (about this there is zero dispute) should pay no price for those actions.

When I wrote seven years ago that we rested our hope on conservative judges who will choose our institutions over Trump, trust me, I wasn’t saying I was confident that they would. I was terrified that that day would eventually come. It came yesterday. The conservative jurists chose Trump. It will stand as one of the blackest days in Supreme Court history.

This article first appeared in Fighting Words, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by editor Michael Tomasky. Sign up here.

He needs to be removed from office

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Justice Stephen Breyer's blunt message to Supreme Court conservatives: 'Slow down' — ABC News

The retired liberal justice spoke to ABC News Live Prime.

There will be a flood of states that require this now

I hope he does say Trump got immunity because then Biden not only can have Trump eliminated but also Beyer himself..He needs to be removed from office

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Trump, gun owners and Jan. 6 rioters: Tough-on-crime Justice Alito displays empathy for some criminal defendants — NBC News

In recent Supreme Court arguments, the former prosecutor has asked skeptical questions about criminal cases against former President Donald Trump, Jan. 6 defendants and gun owners.

Trump, gun owners and Jan. 6 rioters: Tough-on-crime Justice Alito displays empathy for some criminal defendants — NBC News

In recent Supreme Court arguments, the former prosecutor has asked skeptical questions about criminal cases against former President Donald Trump, Jan. 6 defendants and gun owners.apple.news