You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Russia's Invasion of Ukraine (Official Thread)

- Thread starter newarkhiphop

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Json

Superstar

Have a great time.alright we're done here. Have a great day

ft.com

Ukraine crisis tests Xi Jinping’s pivot to Vladimir Putin

Edward White in Seoul, Nastassia Astrasheuskaya in Moscow and Kathrin Hille in Taipei yesterday

7-8 minutes

Russia’s threats to invade Ukraine are forcing China to strike a balance between President Xi Jinping’s growing support for Vladimir Putin and Beijing’s self-interest in the region’s stability, according to analysts.

The crisis, sparked by Putin’s decision to concentrate 190,000 Russian troops near the Ukraine border, remains volatile. Putin and Joe Biden have accepted “the principle” of a summit to ease tensions over Ukraine following warnings from the US president that Russia could invade within “several days”.

China joined Russia this month in opposing Nato expansion, highlighting a new level of co-operation between Xi and Putin.

But Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, told a European security conference on Saturday that “the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of any country should be respected”.

“We hope that a solution can be found through dialogue and consultation that will really guarantee security and stability in Europe,” he added.

His remarks reflected a change from late January, when he offered support for Russia in its stand-off with the US and Nato over Ukraine, saying Moscow had “reasonable security concerns”.

Wang’s tone departed, too, from his own ministry, which has lambasted Biden for stoking tensions.

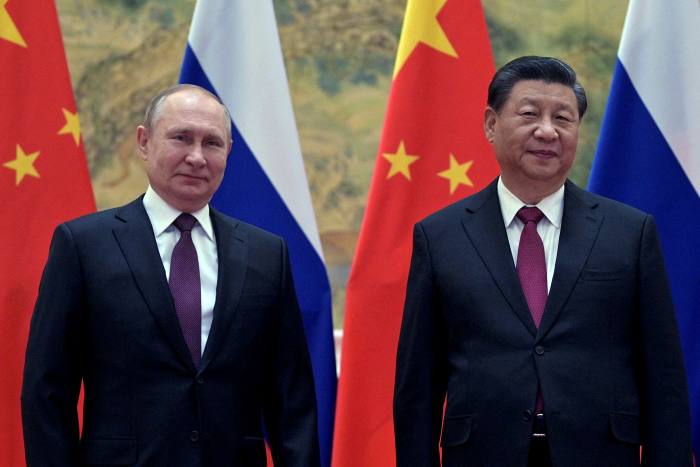

Vladimir Putin, left, and Xi Jinping in Beijing this month. China has joined Russia in opposing Nato expansion © Aleksey Druzhinin/Sputnik/Kremlin/Reuters

Beijing, according to one senior international relations academic at a top Chinese university, must “strike a balance” in supporting Moscow while also not damaging its own military and economic ties with Ukraine.

“There is a common misunderstanding among western media — and even some western officials — that China supports a Russian invasion of Ukraine. That is fictitious,” said the academic, who asked not to be named. “Any military conflict, especially large-scale war, will undoubtedly hurt China’s interests there.”

Wang’s attempt to appear neutral, however, will be tested if the west imposes financial sanctions on Russia.

“China’s decision either to adhere to new western sanctions or to help Russia avoid them will shape escalation pathways and determine the magnitude of economic and political isolation that sanctions impose,” Chris Miller, director of the Eurasia programme at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a US think-tank, wrote in a report.

Analysts said China would seek to separate pushback against the US and Nato, on which it openly supports Russia, from its reservations about a potential violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty.

“China’s and Russia’s support for each other is strongest when they are challenging US supremacy because that’s where their interests are most aligned. When it comes to territorial claims, both have been displaying a rather ambivalent stance towards each other’s behaviour,” said Alexander Korolev, an expert on the Russia-China security relationship at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

China’s interests in Ukraine include billions of dollars in construction contracts as well as telecommunication investments via Huawei and its purchase of Ukrainian military equipment.

Beijing has urged Kyiv and Moscow to revive the stalled Minsk agreement as a path to peace while insisting on adhering to its own policy of non-interference.

Experts diverged over whether Beijing, which has been increasingly inward-focused since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, would seek a higher profile diplomatic role in defusing the tensions, or would stand by as Putin edged closer towards an armed conflict.

The possibility that Russia would launch a full invasion of Ukraine has also presented China with a “gift” to increase its leverage over Moscow, strengthen its energy security, test the west’s sanctions regime and take advantage of a splintering Europe, said resource and geopolitical analysts.

“Russia does not give access to its resources very easily, [but] here China has leverage to say ‘we want to own this’, rather than to simply finance or pay for it,” said Gavin Thompson, an Asia energy expert at consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

Western sanctions over the Ukraine crisis could also deepen Moscow’s dependence on Beijing, while their success or failure would be instructive to Xi for future conflicts with the US, experts said.

“If they succeed in imposing severe costs on Russia, western sanctions threats against China — which could be used in case of a crisis in Asia — would be more credible,” said Miller. “[But] if China helped Russia mitigate the impact of these sanctions, the US would lose an important tool and its ability to constrain China using economic means would be reduced.”

When Xi and Putin met in Beijing earlier this month, the leaders also agreed to increase Russian gas supplies to China.

Thompson believed that the US might find it “very difficult” to target resources shipped directly from Russia to China.

“I think they feel quite bulletproof when it comes to those deals,” Thompson said of Russia’s energy arrangements with its neighbour. “If you can’t touch it and the pricing and the payment structures are mostly outside the standard global banking system, outside of the US dollar system, you can’t really do very much about it.”

There is little transparency over the arrangement’s terms, but experts believe Sino-Russian energy deals have previously entailed Chinese loans and credit facilities. Typically, China lends in renminbi, which Russia then uses to purchase Chinese goods and services.

“[China has] the opportunity to do great deals . . . I think that is the opportunity to push hard on equity ownership of resources,” Thompson said.

Cao Xin, secretary-general of the International Public Opinion Research Center of the Charhar Institute, a Beijing think-tank, said he believed a Russian invasion remained “highly unlikely” but that Moscow appeared to be exploiting fissures between the US and Europe’s big powers to sow divisions in Nato.

Korolev said conflicting interests in their immediate neighbourhoods had not undermined the partnership between Beijing and Moscow, as the countries had pragmatically navigated related crises such as Russia’s armed intervention in Georgia in 2008 and its aggression in Ukraine in 2014.

“China avoided openly voicing support of Russian actions, but they did not directly oppose or criticise Russia either,” he said.

Additional reporting by Maiqi Ding in Beijing

Bruh. Russia has literally done this false flag shelling before in the Finnish-Soviet war. Yeltsin admitted it in 1994!

False flags: What are they and when have they been used?

Shelling of Mainila - Wikipedia

False flags: What are they and when have they been used?

Shelling of Mainila - Wikipedia

here we go

here we go Drop the massive sanctions bomb on those vodka drinking weirdos.. borders meant nothing to Russia after all they’ve done destabilizing numerous countries around the world as well as committing assassination.. this is what happens when you let a mafia state fester..bring Ukraine into NATO and dare Putin to drop those bombs so we can level that shyt hole country to the country.

Secure Da Bag

Veteran

So it's looking like by Monday we'll be in legit disaster mode.

Last edited:

biggest country on earthRussia is a warmongering expansionist state

Tell them to invade North Korea. Take something no one wants

Rickdogg44

RIP Charmander RIP Kobe

ZoeGod

I’m from Brooklyn a place where stars are born.

We can disagree on a lot of things. But Russia for a 1,000 years has been an expansionist empire. They conquer simply to not be conquered. They have committed a lot of atrocities along the way. And yes they have been invaded but the Russian mindset has always been about empireRussia is a warmongering expansionist state

88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

alright we're done here. Have a great day