Just upgraded from a 2015 Trek Alpha 1.2 to a 2020 Cannondale CAAD13 105 Disc. Expecting delivery today, can't wait to get on this joker

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Official Coli Bike/Cycling thread

More options

Who Replied?I get it, people are going to be using it to run a commercial business using city property without a license or paying any taxes.LA really about Cars for real..... sad... How you criminalize bike repair?

To say they won't abuse the public space as that is naive.

Why Does a Long Run Send Me Running to the Restroom?

Runner’s gut — which can include cramping, nausea and a sudden urge to “go” — can plague many runners during intense exercise. Here’s why, and how to avoid it.

Credit...Eric Helgas for The New York Times

Why Does a Long Run Send Me Running to the Restroom?

Runner’s gut — which can include cramping, nausea and a sudden urge to “go” — can plague many runners during intense exercise. Here’s why, and how to avoid it.Credit...Eric Helgas for The New York Times

By Rachel Fairbank

- Oct. 4, 2022

For many runners, long or intense bouts of exercise can lead to a range of digestive issues, like stomach pain, nausea and diarrhea. While gut issues can happen during many endurance sports, experts say they can be especially problematic for runners and are thought to be caused, in part, by a lack of blood flow to the intestines. Some call it runner’s gut, others refer to it as runner’s belly, runner’s trots or a number of other names.

So what is runner’s gut, exactly? And what can be done to avoid it?

What causes runner’s gut?

During a run, when oxygen is supplied to skeletal muscles, “the blood that is supposed to be flowing to the intestines is actually going to your muscles,” said Sam Wu, an exercise scientist at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia.This shunting of blood to the muscles can negatively affect digestion, as “you need a lot of blood flow to the gut when you are digesting food,” said Dr. Lauren Borowski, a sports medicine physician at NYU Langone Health.

This reduced blood flow, combined with physical jostling, can cause nausea, diarrhea, cramping or the sudden need to defecate, especially if you are running on a full stomach, Dr. Borowski said. Such symptoms can be exacerbated if a person is dehydrated, which reduces the overall volume of blood flowing through the body, or if they have hard-to-digest foods moving through the digestive tract, such as complex carbohydrates, fiber or protein. Without enough blood to aid digestion, the body will pass partially or incompletely digested foods.

“Things that are not digested are just flowing through your intestines,” Dr. Wu said. “That’s why you have to run to the toilet.”

For long, sustained endurance efforts, such as running a marathon, the shunting of blood away from the intestines can damage the thin layer of epithelial cells lining the intestine, which control what enters the bloodstream. During a long run, a sustained lack of blood flow can cause these cells to detach from each other and burst open, spilling their contents into the bloodstream.

The idea of intestinal damage may sound worrying, but “for most people, that damage is transient,” said Kate Edwards, a doctoral student at the University of Tasmania who researches gastrointestinal symptoms in endurance athletes.

However, Dr. Wu noted, it’s likely that this intestinal damage can affect the way nutrients are absorbed during a race, leading to less available energy, or cause general gut discomfort. In a small study published in 2021, researchers from Britain found that runners who collapsed during a marathon tended to have higher blood levels of a marker for intestinal damage than those who did not collapse, suggesting that gut issues may have contributed to their collapse.

As Ms. Edwards and her colleagues demonstrated in a separate small study published last year, intestinal damage can be correlated with the intensity of exercise and isn’t specific to running. When compared with runners, cyclists showed similar levels of damage when exercising at similar intensity levels, although they reported fewer overall symptoms of gut discomfort. This damage mostly occurs during high-intensity efforts, Ms. Edwards said, when exercisers were working out at 80 percent of the their bodies’ VO2 max (a measurement of the ability to absorb and use oxygen, loosely tied to effort), compared with when they were working at 60 percent.

“Anything below a moderate intensity, it’s unlikely you are going to get much damage,” Ms. Edwards said.

How to avoid it

Thankfully, there are ways to avoid runner’s gut, Dr. Borowski said. When running long distances, such as when training for a marathon, you need to eat enough to fuel your body, but not so much that it causes gut issues, which is tricky. “What to eat and when to eat is really difficult when it comes to marathon training,” she said.Two to three hours before a run, eat foods that contain simple carbohydrates, like bananas, rather than foods with lots of fiber or complex carbohydrates, such as berries or whole wheat bread.

Training the gut for a long run can be every bit as important as training your legs. Practice what to eat and drink while training, and remember that a race will be more intense than most training runs. Pay special attention to how you feel during training runs done at race pace, rather than just during long, slow runs. On race day, anxiety can also contribute to stomach issues, which is why Dr. Borowski advised not putting any extra strain on your gut and to stick with the usual foods you eat before runs, rather than trying something different. It’s also important to stay hydrated.

One recent study of 46 people concluded that compression socks may help, too. In the study, published in September in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, researchers from Australia looked at the associations between wearing compression socks and intestinal damage during a marathon. Compression socks, which apply pressure to the outermost muscles of the legs, are known to improve circulation.

In the study, those who wore compression socks while running a marathon showed lower levels of a blood marker for intestinal damage than those who did not. Wearing compression socks may not thwart runner’s gut, Dr. Wu said, but it is a relatively simple action that may help minimize the effects.

“If we can improve the blood flow and increase circulation to the deeper parts of the body, then we should be able to promote blood flow back into our digestive system,” said Dr. Wu, who was one of the study authors. “That can help to decrease or reduce the amount of damage that’s done to our gut during high-intensity exercise.”

Rachel Fairbank is a freelance science writer based in Texas.

For 2-Wheel Commuters in LA, ‘Bikepooling’ Brings Safety in Numbers

A UCLA project that uses an app to organize group rides aims to promote car-free transportation for Los Angeles residents.

A bicyclist in downtown Los Angeles. Despite its agreeable climate, LA isn’t known as a welcoming city for bike commuters.

Photo by Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

By

Ngai Yeung

August 23, 2022 at 8:00 AM EDT

On paper, Los Angeles looks like bike commuter country: The sprawling LA basin boasts glorious year-round riding weather and generous expanses of largely flat streetscape.

But only about 1% of LA commuters get to work by bicycle, according to the US Census Bureau, a figure that reflects the challenges that riders face in a freeway-laden city that’s been optimized for the automobile. Protected bike lanes are rare, and the streets of Southern California are among the most dangerous for two-wheeled travelers. Between 2011 and 2020, 276 cyclists were killed in traffic in Los Angeles County — the most of any US county. In 2018, Bicycling Magazine declared LA the “Worst Bike City in America.”

To encourage more Angelenos to take to the streets by bike — and keep them safe there — a demonstration project set to launch this fall will encourage residents from low-income neighborhoods to bike to work in groups.

“It’s not just an informal group of cyclists — it’s a public transportation system based on bicycles,” said Fabian Wagmister, an associate professor at the University of California Los Angeles School of Theater, Film and Television and the founder and principal investigator of the Civic Bicycle Commuting research project, also known as CiBiC.

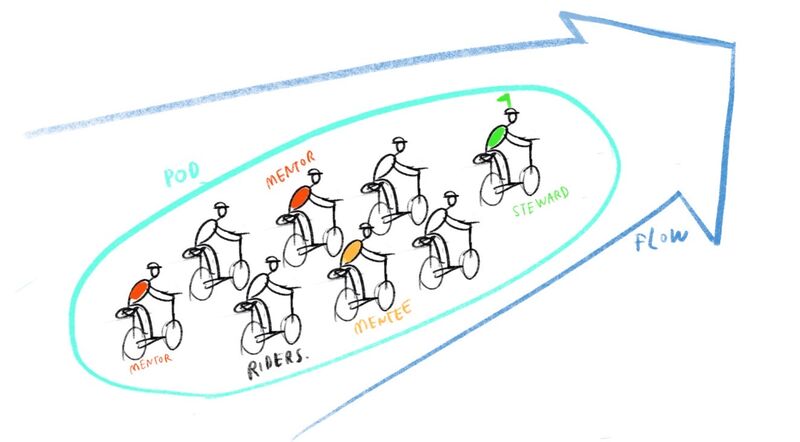

The concept is simple: Wagmister describes CiBiC as “carpooling, but on bikes.” In the pilot program set to start Oct. 1, users put their destination and arrival time in an app that determines the best route — or “flow” — to bring them to work. The app then pairs bike commuters with each other in groups of up to 12, known as a pod, led by two experts whose job is to prioritize safety on the road over efficiency.

A group of CiBiC riders road-test a “flow” in Northeast LA in advance of the program’s October launch.

Photo courtesy of CiBiC

Bikepooling, Wagmister hopes, will help participants save money and improve their health and well-being while reducing vehicle emissions in a traditionally car-centric city. Armed with a $1 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s Civic Innovation Challenge, researchers at UCLA and community partners will focus on five Northeast Los Angeles neighborhoods — including Chinatown, Solano Canyon and Lincoln Heights — which are home to lower-income communities of color. According to a CiBiC survey, 73% of respondents in the area the pilot serves drive for commutes of less than five miles.

“It’s such a LA thing to do, but people would drive their car for a commute that’s less than a mile,” said Andres Ramirez, executive director of the advocacy group People for Mobility Justice, one of CiBiC’s partners. “But it’s very expensive to keep up with the gas prices that are constantly fluctuating, and in a city that’s also very expensive to live in.”

Wagmister, the director of the Center for Research in Engineering, Media and Performance at UCLA, fell in love with biking in LA after he started riding to work daily (at age 50). To encourage others to take up the mode, he assembled a team of professors and community organizations. “We decided to come up with an idea for trying to support low-income communities to commute by bicycle,” he said. “The most important thing for us is that we’re not a project for bicyclists — we’re a project of bicyclists for other people. This project is really meant to enable new riders more than experienced bicyclists.”

When CiBiC surveyed area residents, the team found plenty of enthusiasm for biking — but also unease. “So many people say they would like to commute by bike, but were afraid to do so,” he said. “And so we started thinking, how can we make it safer?”

Since construction of protected bike infrastructure lags in LA, the team decided to create what they call human infrastructure. CiBiC’s pods of riders will be led by two paid expert bikers, including a “steward” in the front and a “mentor” tailing at the back to communicate safety measures and signal turns with verbal and hand signs. When possible, riders will bike two abreast, to take up an entire lane, and all must match the pace of the slowest rider.

A bikepool “pod” in action.

Courtesy CiBiC

“We’re a car, basically — we take up the lane, we stop at every stop light, we respect every rule of the road,” Wagmister said.

New riders can also request a bike mentor for one-on-one help to get them started. “It’s not about an app — our project is more about people helping people,” Wagmister said. “We want your commute not to be the worst part of your day, but a good part of your day.”

The bikepooling pilot will offer first-time riders a $50 cash incentive funded by the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority to join the program. Prospective riders fill in an online form and download the app to join, and may be eligible for up to $100 for completing extra rides. The CiBiC app is available in three languages — English, Spanish and Chinese — to reach a broad pool of potential users.

Though routes are charted out on the app, they are pre-vetted by “flow curators” — experts who are paid to design the safest route and then road-test it to ensure that conditions are as safe as possible for beginning riders. “There’s a lot of benefit to riding with someone, like assistance with your bike’s flat tire,” said flow curator Austin Boldt. “You’re also a bigger presence on the road, so there’s an added safety bonus as well. And if you fall, you have another rider there to help you.”

Research supports the notion that, for bikers, there is indeed safety in numbers: Several studies have shown that group riders are better protected from motorists. For children, that principle has inspired scores of formal and informal “bicycle buses” that allow kids and parents to gather for group rides to and from school.

CiBiC isn’t the first attempt to promote bikepooling for grown-ups — existing mobility apps offer bikepool options, and local transit agencies have also launched initiatives. But Wagmister believes that the UCLA program offers a first-of-its-kind combination of technology, funding and community outreach: “We have found nothing as extensive and as ambitious or structured as our system.”

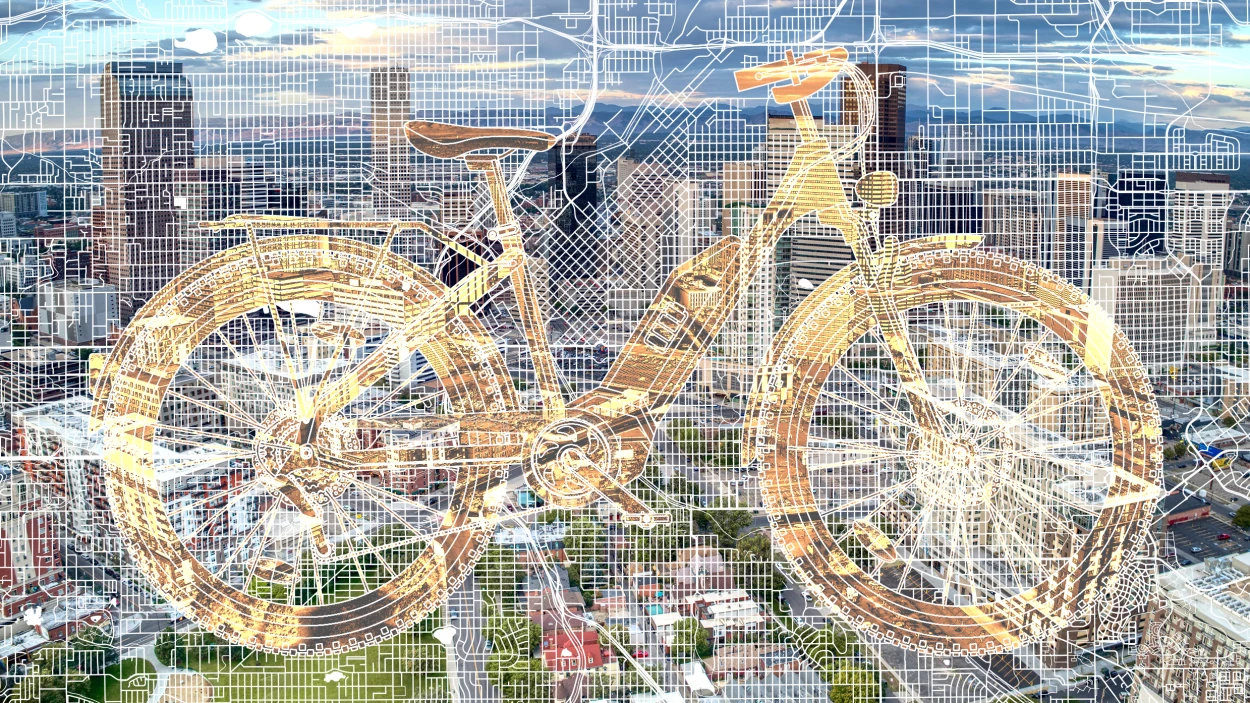

There’s even a public art component of the project. Information about the length and routes of each ride, as well as weather and traffic data, will be collected and used to create what the team calls “interpretative cartography.” Riders will change the artwork in real time as they log more miles, creating an ever-evolving portrait of LA by bike.

“It’s like closing the loop with riders,” said Jeff Burke, associate dean of the School of Theater, Film and Television at UCLA and co-principal investigator of CiBiC. “You’re riding not just for function, but you’re also riding as part of a community.”

To gather enough data for research conclusions, CiBiC is looking to launch with between 100 to 200 regular riders by October. After testing ends and rides officially begin this fall, the team at UCLA hopes to eventually hand off CiBiC to a community organization, city government or LA Metro, the region’s transit agency.

Recently, the National Science Foundation granted an additional $200,000 to CiBiC to study potentially expanding the program in Los Angeles County and replicating it in other cities.

“Hopefully we can convince city government and institutions like Metro to fund at a very large scale,” Wagmister said. “Our thesis is that people will say, ‘Yeah, this is a great way of going to work.’ Then we can engage in scalability and even duplicability.”

Skarper’s Clip-On Motor Turns a Regular Bike Into an Ebike

We hit the saddle with a new “clip-and-go” motor that electrically drives the rear wheel of nearly any bike with disc brakes.

Skarper’s Clip-On Motor Turns a Regular Bike Into an Ebike

We hit the saddle with a new “clip-and-go” motor that electrically drives the rear wheel of nearly any bike with disc brakes.

PHOTOGRAPH: SKARPER

- https://www.facebook.com/dialog/fee...-share&utm_brand=wired&utm_social-type=earned

- https://twitter.com/intent/tweet/?u... Turns a Regular Bike Into an Ebike&via=wired

- https://www.wired.com/story/skarper...tter&utm_social-type=owned&utm_medium=social#

THERE’S NOTHING REVOLUTIONARY about electric bikes. Ogden Bolton Jr. was awarded the first US patent for one in 1895. His battery-powered bicycle featured a hub motor mounted inside the rear wheel, with the battery attached to the cross bar. Two years later in Boston, Hosea W. Libbey invented an electric bike that was propelled by a motor tucked into the hub of the crank-set axle.

And while battery and motor technologies continue to evolve, those basic propulsion methods remain relatively unchanged—despite ebike sales reaching $41 billion in 2020 and expected to grow to $120 billion by 2030. Obviously Ogden’s patent is only a distant cousin to the latest high-performance peddlers, but even the most modern machines follow the same basic design principles.

In a shop tucked down a cobblestone street in Camden, north London, Alastair Darwood has invented a clip-on motor and battery pack that can turn any bike with disc brakes into an ebike. It’s an innovative, exciting proposition, and one that has caught the attention of six-time Olympic champion and 11-time world champion cyclist Chris Hoy, who has invested in the project and has been heavily involved in its development.

The Skarper requires you to replace your bike’s rear disc-brake rotor with its DiskDrive, which otherwise looks and works just like a traditional disc-brake rotor. Then a 3-kilogram (6.6 pound) unit housing the battery and a 250-watt-hour motor clips onto the bike frame. The DiskDrive rotor slots into the clip-on unit, where it engages with the gearing inside. The motor's internal gearing turns the special brake rotor, spinning the rear wheel. A small sensor also clips to the bike's crank, where it measures your speed and cadence as you pedal.

Once fastened in place, the Skarper offers a claimed 37 miles (60 km) of assisted cycling at or just below maximum legal speeds: 25 kph in the UK and EU, and 18 mph in the US. And once you get where you’re going, you can unclip the unit and stuff it in a bag, then recharge the battery in just 2.5 hours.

Take a Brake

PHOTOGRAPH: SKARPER

Skarper’s story started during the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, when Darwood, a keen cyclist and inventor in the medical space, started looking for an ebike. He wasn’t prepared to spend enough to get a quality ebike, but neither was he convinced by current ebike conversion methods that retrofit a standard bike with a motor and battery.

Looking at existing conversion kits, Darwood realized that almost all of them require you to either swap out your wheels for powered wheels or add a hub motor, both of which are drastic alterations. With new ebikes, he felt the brands were beholden to the motor manufacturers and had to build the entire bike around someone else's kit, while also stashing batteries on the frame and running cables all over. Darwood wondered if there was a less invasive way to power a bike, and he turned his attention to disc brakes.

“Look at any bike and the geometry around a disc brake is universal. The back wheel is an industry-standard design,” Darwood says. “I looked at the wheels and disc brakes and realized there was quite a bit of space between the back of the rotor and the wheel as it tapers into the tire, and I wondered if you could actually drive a bike wheel only using the disc brake.”

Darwood struck upon the idea that you could extrude material from behind the disc brake and fit a gear running around the outside in the recess. In this design, the disc still works to stop the bicycle when needed, and your bike otherwise rides as normal. But when the Skarper unit attaches to the rotor, two pins hold the disc securely in position while a third pinion gear drives the wheel. It’s an ingeniously simple solution.

Of course, this system requires replacing your stock rear disc-brake rotor with the DiskDrive. This conversion adds around 300 grams (10 ounces) to the weight of the bike. That might give a Tour de France racer some pause, but most of us won’t be inconvenienced by the weight. More significantly, the motor system creates no additional drag, and you can still freewheel while riding.

The other bonus is the fact that any bike frame engineered for disc brakes has already been designed to cope with any additional force applied by using the Skarper. This was crucial to the viability of the system, and it was only when Red Bull F1 engineers looked into the issue and confirmed their force calculations that the Skarper project was greenlit.

Initial Impressions

Press the white button in the center of the ring to activate the motor drive.

PHOTOGRAPH: SKARPER

Before we talk about cost, competition, and implications for the evolution of ebikes, you might be wondering what the Skarper feels like to ride. I tried the system on two very different bikes: a top-of-the-line, ultralight Cannondale gravel bike, and a hefty sit-up-and-beg, super-comfy commuter.

Connecting the Skarper unit to the frame is brilliantly simple. The rear section slots onto the DiskDrive at two points, and the tapered front end clips securely into a small bracket that you mount to the bike frame. Press the only button on the unit, wait for the status light to come on, and you’re ready to ride.

Riding the backstreets and gentle hills of north London, I was hugely impressed by the help offered by the Skarper and the instantaneous pull I felt as soon as I started to pedal. The assistance isn’t overbearing, and it won't freak out first-time ebike riders with inconsistent, aggressive acceleration. It simply works, just like a decent ebike should, helping when you need it but not making you feel like you’re on a moped.

I tried the Eco and Max modes, and while full power was more fun, both offered a solution to avoid getting sweaty on a daily commute. Given the compact size and simplicity of the unit, this is a huge accomplishment.

What surprised me most during the test, however, was the fact that the big, goofy step-through commuter bike was more fun to ride than the ultralight gravel bike. It bounced along with a real sense of joy, feeling like an infinitely superior pay-per-ride city bike. Maybe I didn’t enjoy the pro design because it’s the sort of bike that is fast, fun, and engaging to ride without electric power. In truth, it’s the bike you hurtle to work on, under your own steam, and then mosey home on, with Skarper taking the strain.

The prototype needs a bit of finessing. In my tests, the bearings made a bit of a racket (apparently caused by letting a BMX rider do jumps with it at a trade show), and it pulled a little too forcefully at times when turning through tight corners. But even after my short ride on this preproduction model, I could easily see the potential.

Puzzling Price Point

There’s no escaping the debate about cost. The Skarper is expected to retail for around £1,000 ($1,190), a sum most casual cyclists would rather just spend on a complete ebike. A quick search on Amazon reveals 577 complete ebikes for sale at a lower price. So how can the company justify such an outlay?

“There’s a real value fallacy in buying a £1,000 ebike,” Darwood says. “Battery and motor component costs are high, so you’re essentially paying for a motor, battery, and a bike built with unbranded parts that wouldn’t cost more than £100.”

“So you can find what appears to be a bargain of an ebike, but the truth is, if you’re buying from a leading manufacturer such as Specialized, Giant, or Trek, there’s almost nothing available for less than £2,000. So what we’re saying is, go to a bike shop, spend £1,000 on a hybrid commuter bike with quality components, and then buy a Skarper,” Darwood says.

On the face of it, that’s an awful lot of work and expenditure for the average bike commuter to be bothered with. But the fact remains that you don’t need to buy a new bike to use the Skarper; you may be able to install it on the bike you’ve been riding for years, as long as it has disc brakes.

Chris Hoy on a Skarper-equipped bicycle.

PHOTOGRAPH: SKARPER

“It’s an entirely new system, and being able to clip it on and off is a unique selling point,” says Chris Hoy. “My dream is that in 10 years, in any major city, you’ll see people clipping a Skarper onto a bog-standard bike and enjoying the benefits of assisted pedaling.”

This vision is certainly appealing to more than just a superstar cyclist who's invested in the company. Anyone who's had a battery die on them while riding a heavy ebike, or anyone who lives in an upstairs flat and doesn’t want to lug an ebike up and down the stairs has yearned for something simpler and lighter.

As a regular non-Lycra-clad London cyclist, I can definitely see the appeal of the Skarper, and I imagine most people would enjoy a little extra help on the way home from work, at stop lights, or up a particularly nasty hill. But at the current pricing it will remain a brilliantly innovative solution for a small group of riders.

Trouble is, I'm one of them. For me, a stand-alone ebike doesn’t yet make practical or financial sense. But the ability to clip a motor onto a compatible bike I already own is a tempting proposition indeed, and a whole lot easier to sneak into the house than yet another bike.

Changing Gear

An exploded view of the DiskDrive.

PHOTOGRAPH: SKARPER

In my time with the team at Skarper, bike components and intellectual property came up a lot, and what became clear is that, aside from sales ambition, the company wants to become part of the cycling establishment. By making its DiskDrive disc-brake rotor universal, the company aims to be an industry-standard choice in the same way brands like Shimano and SRAM are.

Manufacturers who fit a DiskDrive onto their existing bikes are essentially making the machine “ebike ready,” which slings the doors open for third-party motor and battery innovation. And, as Skarper COO Uri Meirovich alludes to, this will include a range of different-powered propulsion units, including an exciting solution for mountain bikes, currently in development with the help of Red Bull Advanced Technologies.

Skarper is by no means the only electric bike-conversion kit available, though it's the only one that doesn’t compromise the ride of the original bike and can easily be removed. Its closest cousin, the excellent Swytch, is lightweight, universal, and relatively simple to install—and boasts a 50-km range with a two-hour charge—but it still requires you to replace a wheel, run cables, and find a place for the battery.

Other worthy mentions include the Pendix eDrive torque-based mid-drive unit, which handily has a dealer network to help sidestep the complex installation, while you’ll find a wide range of hub-and-wheel conversion kits from Chinese e-mobility specialist Bafang, not to mention countless bargain basement, potentially terrifying unbranded options on the likes of eBay, Amazon, and Wish.

When it hits shops in 2023, the Skarper will be one of the simplest ebike conversion kits. The scope to be able to buy multiple DiskDrive rotors and give all your bikes the “ebike ready” treatment is a compelling one, and I can also see the benefit of having a shared Skarper unit at home. Yes, it's expensive, and explaining why it constitutes “value for money” will be a constant and tricky conversation. But with the rapidly changing landscape of urban mobility, and the obvious health benefits of regular cycling, it is a welcome change.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/QDT37QVKNFGVNMIM4SSS5JL4RQ.jpg)

Philadelphians are fighting brazen bike theft with technology and their own wits

Nothing seems to stop Philly’s determined bike thieves, but owners are equally tenacious in recovering their stolen property.

Philadelphians are fighting brazen bike theft with technology and their own wits

Nothing seems to stop Philly’s determined bike thieves, but owners are equally tenacious in recovering their stolen property./cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/QDT37QVKNFGVNMIM4SSS5JL4RQ.jpg)

Lajuane Stewart, 32, with his bike in Center City Philadelphia. After multiple thefts, he has developed a strategy to keep his bike secure.Tyger Williams / Staff Photographer

- by Frank Kummer

- Updated

Oct 10, 2022

Lajuane Stewart’s bikes over the years have been his economic engine to deliver Grubhub and Uber Eats, so he is rightfully incensed whenever one gets stolen — which has been more often than he can recall.

Two years ago, he purchased a new, expensive electric bike as a replacement to help with his 100-mile rounds. This time, he mounted an Apple AirTag GPS device under the seat — a small device that helped him track, surprise, and confront two thieves caught in the act.

“I have to keep track of the bike,” Stewart said. “If I don’t have it, I’m not making money.”

Nothing seems to stop Philly’s determined bike thieves, who use bolt cutters, pry bars, power tools, and even low-tech devices such as a 2x4 to wedge between locks and posts until one or the other gives way. Most don’t seem to care that they are often captured on video.

Since 2018, 6,416 bicycles have been reported stolen to Philadelphia police, according to data supplied by the department, and surely an undercount because so many thefts go unreported.

Stewart is just one of many Philadelphians who have decided to try to hunt down their bikes or find the thieves, who are undeterred by Kryptonite locks and steel cables latched to posts on bustling city streets, stowed in yards, and even hidden in parking garages.

But cyclists are equally tenacious. They know their stolen-bike report isn’t going to get much attention with police dealing with a surge in violent crime.

So they use technology as an electronic bloodhound, help one another track sightings, and, even though it might not always be wise, set up their own stings and confront thieves.

They bond through social media such as the Facebook group Philadelphia Stolen Bikes, where they post pictures of taken Treks, captured Cannondales, and ripped-off Raleighs. They post doorbell videos and share surveillance. One post shared details of an ad hoc chop shop under I-95 where thieves can grab parts they need.

Some victims get lucky and recover their bikes; most do not.

Tracking a stolen bike via Uber and GPS

The first time Stewart’s bike was stolen it was locked to a steel post on a city street while he made a food delivery. He saw it as a lesson learned.“There’s really nothing you can do to stop your bike from being stolen,” said Stewart, who lives in University City.

He bought the $2,500 Juiced bike to help make his business more efficient. In January, the bike was locked outside the Fashion District when it was stolen. Stewart dashed inside to where police were patrolling and reported the theft.

“I hope you find it,” one of the officers told him without much encouragement.

Stewart immediately beckoned an Uber and followed the moving bike in real time on his phone through the AirTag’s GPS.

“I tracked it to a pawnshop where the guy was still inside trying to sell it,” Stewart recalled. “I told him, ‘It’s mine, and I tracked you on the phone.’ He just looked at me, and said, ‘OK, here you go.’”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/363ZBO2MA5FQLHQBADTPTTVWEQ.jpg)

Lajuane Stewart, 32, of Germantown, shows how he tracks his bike through GPS.Tyger Williams / Staff Photographer

Fed up after that theft, Stewart paid $100 for a Kryptonite lock with insurance, but it still wasn’t enough.

In April, he secured the bike with its new lock at 30th Street Station, figuring there was enough pedestrian foot traffic to deter thieves. He boarded a train for a two-day trip to Virginia. The bike was gone when he returned. Stewart turned on the GPS once again.

“I could see the bike was in Southwest Philadelphia,” said Stewart, who brings a friend along when he confronts thieves. “I found the guy at 61st and Woodland. I called to him and said, ‘Is that your bike?’“ He lied about the bike, Stewart said, but also said it wasn’t his and “gave it back without trouble.”

Now, when Stewart locks his bike, he also removes the battery so the bike is difficult to ride.

Identifying a suspect through social media

When Misha Prostorov of South Philly came across a vintage 1985 HPV bike for sale, he knew he had to have it. The bike was made in his hometown of Kharkiv, Ukraine, which was recently retaken from Russia in the war.Using multiple locks, he secured the bike Aug. 17 to a street sign and left it overnight. The bike was old “and not very attractive,” Prostorov said, believing no one would want to steal it.

He was wrong.

Leaving it overnight “was my first mistake,” Prostorov said. “It doesn’t matter how many locks you have on it.”

“I don’t even understand why someone would steal it,” he said. “You wouldn’t get much money for it. It’s very upsetting.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/FQPCHNHQ7FFPNGYS3ZN7IXXPAA.jpg)

Misha Prostorov riding his 1985 HPV bike, which was made in his native hometown of Kharkiv, Ukraine. He had a strong emotional tie to the bike, which was stolen in August.Misha Prostorov

Prostorov launched his own investigation.

“I talked to a few homeless people who hang around Seventh and Washington and showed them a picture of my bike. One said that he saw a person with the bike the previous night. He was carrying it and trying to sell it, and they gave me a description of him.”

Through Facebook, Prostorov identified a suspect who had previously tried to sell a friend’s stolen bike, and the homeless people identified him as the same man. Prostorov went to where he believed the suspect lived on Oregon Avenue.

“I was able to locate a bunch of frames, rims, and tires just laying on a sidewalk near one house,” Prostorov said. “It seemed to me like it was a chop-shop setup at the house. So I kept going back there. Then I saw the exact person who had stolen my friend’s bike a year ago.”

Prostorov went to police, but they told him there was not enough evidence to pursue the theft. He still hopes to recover the bike.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/IFCCMWS3OREMBAVJP4KCRD3IEQ.jpg)

While Misha Prostorov was trying to track his stolen bike in August, he found this bike pile, which he believes was part of a chop shop.Misha Prostorov

Collecting evidence through nearby security cameras

Jordan Chu, a pediatrician, moved to Philadelphia from Scranton a few years ago. He began cycling in 2021 during the pandemic, ultimately becoming victim of a brazen theft that’s left him in search of the second bike that’s been stolen in the short time he’s lived in the city.After the first bike was stolen, Chu, 29, purchased a vintage Trek bike “still in tip-top shape” that was used by the USPS team in a Tour de France run. “It was the smoothest ride I’ve even been on,” he said.

That ride lasted less than a month.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/R3MZAJTTRNAPBJLCWF4ZU665JE.jpg)

Philadelphia pediatrician Jordan Chu with his Trek bike used in a Tour de France. The bike was stolen in broad daylight in August across from his office in Center City.Jordan Chu

Chu locked the carbon-fiber bike one weekday morning in August to a rack across from his office near busy Eighth and Chestnut, believing it was one of the safest spots in Philly.

At lunchtime, as people walked by, a man used a long metal pipe to pry and hammer the lock until it gave way. He dropped the pipe and left with the bike.

Chu left work at 7 p.m. and discovered that the bike was missing.

“I was absolutely shocked” by the daytime theft, Chu said. “It was right outside of a very busy street where cops frequently walk. So I was stunned to see the effort that he put into it. … He just knocked the lock until it broke and left the pipe he used just sitting there.”

Chu persuaded the security department of a nearby building to share the video that captured the theft.

“As I was about to walk away, some police happened to be biking by,” Chu recalled. “So I stopped them and made a report, but they basically said there was essentially nothing they can do unless I found the person who stole the bike, called them, and said, ‘Hey, I need your help to get my bike back.’”

Courtesy of Jordan Chu

Security footage shows a man stealing a locked Trek bicycle belong to resident Jordan Chu from a bike rack in Center City in August.

Setting up a civilian sting — with help from police

Jonathan Stanwood, a Center City lawyer, turned to social media when his bike was stolen. He joined the Facebook group for stolen bikes and regularly monitored it out of curiosity. Eventually, he came across a woman’s post about seeing her own stolen bike listed on Craigslist for $250.The owner asked the group’s advice on meeting the seller to try to get her bike back. Stanwood, fearing she would act alone, offered to help. (The woman did not respond to a request from The Inquirer to tell her tale. But Stanwood agreed to share his part of the story from March 2020.)

“I said, ‘If you’re going to set this guy up, don’t do it alone,’” Stanwood said.

Police and bike groups don’t recommend stings because of the potential danger. And they are ambivalent about buying back a stolen bike, fearing it just encourages theft.

Regardless, Stanwood and the woman reached out to the seller, suspecting he was the thief. Stanwood also reached out to 17th District police, who said they would not take part in what Stanwood described as a sting but would monitor it.

Stanwood and the woman rented a Zipcar and arranged to meet the suspected thief in Grays Ferry.

“We were on the street corner at about 7 o’clock at night, and it was still somewhat daylight, and the guy comes up on a bike,” Stanwood recalled. “He looked like he was in his early 20s.”

The man arrived on a bike that didn’t belong to the woman. After some banter, he left and came back with her bike.

“I said, ‘Dude, this is her bike,’ You stole it,’” Stanwood recalled.

The suspect started to walk away when two police officers arrived in an SUV and confronted him. The man denied stealing the bike, and police let him leave. The woman got her bike back, but police said there was not enough evidence to connect him to the theft.

“She rode her bike away calmly and I drove the Zipcar back,” Stanwood said. “And that was it.”

Published

Oct. 10, 2022

Why E-Bikes Could Change Everything

Cities take on transportation’s whopping carbon footprint

Why E-Bikes Could Change Everything

Cities take on transportation’s whopping carbon footprint

By David Zipper

Illustrations by Nan Cao

October 1, 2022

As e-bike converts will attest, zooming through your neighborhood and effortlessly conquering the steepest of hills is a total blast. The added storage capacity of e-cargo bikes makes them especially viable as vehicle replacements. And at about $1,000 for a solid entry-level electric bike (high-end versions and e-cargo bikes can be much pricier), they're affordable. Best of all, using an e-bike in lieu of a car helps reduce the whopping 27 percent of US greenhouse gases that come from transportation.

Why Get an E-bike

In 2017, British researchers offered 80 people in Brighton a free e-bike for up to eight weeks. The average participant drove 20 percent fewer miles while they had an e-bike, and afterward 70 percent of them said they wanted one of their own. Even in a country as vast as the United States, almost 60 percent of car trips are under six miles—and e-bikes offer powerful advantages for daily trips. Steep inclines, for instance, become a cinch. An e-bike's extra boost lets you comfortably match the speed of car traffic while en route to a meeting—and avoid arriving in a pool of your own sweat. Particularly for those with limited mobility (like Tour de France champion Greg LeMond, who is now designing his own e-bike), the addition of battery power can be life changing.

Every trip taken by e-bike instead of automobile is a win for the planet. Even electric cars require far more resources than e-bikes to construct and operate (at 1,800 pounds, the battery of the Ford F-150 Lightning weighs as much as 233 Rad Power e-bike batteries). And according to one market estimate, e-bikes now outsell electric cars in the United States; almost 800,000 were purchased in 2021. But a look across the Atlantic shows that much room for growth remains: Germany, a country with just about a quarter of America's population, sold 1.2 million e-bikes in the first six months of last year alone.

How We Can Accelerate E-bike Adoption—and Car-Trip Replacement

Improved Bike-Lane Infrastructure

Only the bravest of cyclists are willing to share a traffic lane with cars roaring by at 40 miles per hour. Studies show that painted bike arrows on pavement—so-called sharrows—actually make injuries more likely, not less. The good news is that if cities install dedicated bike lanes, more people will consider cycling—especially if the lanes are physically protected from cars.

Last year's federal infrastructure bill set aside $6 billion to create the Safe Streets and Roads for All program, which could fund a bevy of new bike lanes. But the Feds can do only so much on their own. States, cities, and counties manage most transportation planning, so we need state and local officials to not only ensure that e-bikes are legal for all to ride (New York City has tried to crack down on delivery workers' use of e-bikes, for instance) but also incorporate new bike routes into their road redesigns. And while they're at it, state and local officials should expand commuter benefits to include perks for all bike riders. Planners should envision a complete network of safe cycling routes crisscrossing the region. Minneapolis city planners recently took a cue from Italy, where such networks are called bicipolitanas, or "bike subways."

Financing

Although an e-bike is cheaper than a new car, many people can't just drop $1,000. To the frustration of bike advocates, no federal incentives for e-bikes were included in the energy and climate legislation brokered over the summer. In the absence of a national policy, some states and cities are devising their own e-bike incentives, such as an income-based rebate of up to $1,000 that's been proposed in Connecticut and the rebate of up to $1,700 that Denver began offering to residents earlier this year. If policymakers want to think bigger, they could draw inspiration from France's "e-bike for clunkers" program, which offers up to 2,500 euros toward an e-bike purchase for those trading in a car.

Parking

Many people are understandably wary of leaving their pricey e-rides on the street. To help, cities could provide storage, along the lines of what Jersey City, New Jersey, has done by promising to build 29 bike storage facilities by the end of 2022. BikeLink has an extensive network of safe bike parking on the West Coast and is expanding. For an example of how far ahead some other countries are, see the "bicycle park" below the train station in Utrecht, the Netherlands, which can accommodate over 12,000 bikes.

Employers, too, can give e-bikes a tailwind. Businesses often offer free car parking to employees but negligible facilities for cyclists, especially those using e-cargo bikes. At a minimum, providing secure bike storage can allow commuters to consider leaving the car at home; more ambitious employers might add the option of a "parking cash-out," a financial inducement not to drive (saving the employer money on providing car parking).

Test-Drives

E-bike libraries offer people a chance to try out an e-bike without committing to buying one. Local Motion, a nonprofit organization in Vermont, runs public e-bike libraries in Burlington and Brattleboro, as well as two others that rotate around the state. Last year, officials in Oakland, California, received a $1 million state grant to launch an e-bike library program focused on low-income neighborhoods. Many cities have added electric bikes to their public bike-share fleets, including New York City, Austin, and Washington, DC, while a few, like Charlotte, North Carolina, have gone all-electric. Some e-bike subscription services, including Dance, let you rent bikes on a monthly basis.

Biking in New York City Is 25 Times More Dangerous Than in Vancouver, Study Finds

The study by the International Transport Forum shows some cities have virtually eliminated cyclist deaths. Others, not so much.

Biking in New York City Is 25 Times More Dangerous Than in Vancouver, Study Finds

The study by the International Transport Forum shows some cities have virtually eliminated cyclist deaths. Others, not so much.

By Aaron Gordon

October 17, 2022, 11:20am

CREDIT: EDUCATION IMAGES / CONTRIBUTOR VIA GETTY

A cyclist in New York is 25 times more likely to die than a cyclist in Vancouver and is about as likely to die as a cyclist in Auckland or Buenos Aires, according to a new study by the International Transport Forum, an intergovernmental organization.

“Cities should do more to protect pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcycle riders on their streets,” the report found. “Every minute, someone in the world dies in urban traffic. Local governments are at the forefront of efforts to prevent these needless road deaths.”

The study analyzed road fatality rates in 32 benchmark cities in Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries from 2010 through 2020 to see how many hit the goal of halving their road fatality rates during that time. Only Warsaw hit the target, reducing road fatalities by 56 percent, but Edmonton (49 percent), Barcelona (48 percent), and Oslo (45 percent) came close. New York City reduced road fatalities by 19 percent during that time, which is not nothing—especially since the United States as a whole was one of only two countries, Colombia being the other, in the dataset where road fatalities increased nationwide during the decade—but still fell in the bottom fourth of the cities studied because road fatalities have been generally declining in major cities across the world.

But the most revealing statistics in the report concern bicycle safety. The report generously frames the “large differences between cities” as “room for progress.” A less charitable but equally true framing is that some cities are politically willing and able to take street space away from dangerous private vehicles and design them for safe and comfortable cycling on a massive scale. That strategy works: Some cities have born the fruit of that strategy by having fewer of their residents die while biking. Other cities willfully ignore that strategy or roll it out at a glacial pace.

In this tale of cities, two are especially noticeable. On the one hand is Vancouver, which according to the study had an average of just five cycling fatalities per billion passenger trips from 2016 to 2020. On the other is New York City, which had 123 fatalities per billion passenger trips over the same period. In between are cities like Copenhagen (19 per billion trips), Paris (34), and Buenos Aires (85). Even worse than New York is Bogotà with 223 fatalities per billion trips, highlighting the city’s mixed reputation for both encouraging a robust cycling culture and having to deal with notoriously aggressive drivers.

As the report notes, the solution to this problem is annoyingly simple. The section immediately following these statistics describes an experiment with flex posts—plastic structures that form a semi-permanent barrier between cyclists and cars—in the Camden district of northwest London. After the flex posts were installed, there was a 70 percent increase in cycling in both directions along with a 50 percent reduction in the number of crashes and the severity of their injuries. Flex posts are not as effective as completely separated bike lanes with hardened barriers but they are cheap and easy to install. Other proven successful measures the report recommends are citywide speed limits of 30 kilometers per hour (18 miles per hour) where cars, pedestrians, and cyclists mix as well as automated speed enforcement. It also recommends “reallocating road space in dense urban areas” to more pedestrian and bike-friendly modes, therefore making cities safer.

A cyclist in New York is 25 times more likely to die than a cyclist in Vancouver and is about as likely to die as a cyclist in Auckland or Buenos Aires, according to a new study by the International Transport Forum, an intergovernmental organization.

“Cities should do more to protect pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcycle riders on their streets,” the report found. “Every minute, someone in the world dies in urban traffic. Local governments are at the forefront of efforts to prevent these needless road deaths.”

The study analyzed road fatality rates in 32 benchmark cities in Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries from 2010 through 2020 to see how many hit the goal of halving their road fatality rates during that time. Only Warsaw hit the target, reducing road fatalities by 56 percent, but Edmonton (49 percent), Barcelona (48 percent), and Oslo (45 percent) came close. New York City reduced road fatalities by 19 percent during that time, which is not nothing—especially since the United States as a whole was one of only two countries, Colombia being the other, in the dataset where road fatalities increased nationwide during the decade—but still fell in the bottom fourth of the cities studied because road fatalities have been generally declining in major cities across the world.

But the most revealing statistics in the report concern bicycle safety. The report generously frames the “large differences between cities” as “room for progress.” A less charitable but equally true framing is that some cities are politically willing and able to take street space away from dangerous private vehicles and design them for safe and comfortable cycling on a massive scale. That strategy works: Some cities have born the fruit of that strategy by having fewer of their residents die while biking. Other cities willfully ignore that strategy or roll it out at a glacial pace.

In this tale of cities, two are especially noticeable. On the one hand is Vancouver, which according to the study had an average of just five cycling fatalities per billion passenger trips from 2016 to 2020. On the other is New York City, which had 123 fatalities per billion passenger trips over the same period. In between are cities like Copenhagen (19 per billion trips), Paris (34), and Buenos Aires (85). Even worse than New York is Bogotà with 223 fatalities per billion trips, highlighting the city’s mixed reputation for both encouraging a robust cycling culture and having to deal with notoriously aggressive drivers. As the report notes, the solution to this problem is annoyingly simple. The section immediately following these statistics describes an experiment with flex posts—plastic structures that form a semi-permanent barrier between cyclists and cars—in the Camden district of northwest London. After the flex posts were installed, there was a 70 percent increase in cycling in both directions along with a 50 percent reduction in the number of crashes and the severity of their injuries. Flex posts are not as effective as completely separated bike lanes with hardened barriers but they are cheap and easy to install. Other proven successful measures the report recommends are citywide speed limits of 30 kilometers per hour (18 miles per hour) where cars, pedestrians, and cyclists mix as well as automated speed enforcement. It also recommends “reallocating road space in dense urban areas” to more pedestrian and bike-friendly modes, therefore making cities safer.

The report also underscores the fallacy of the popular assumption that U.S. road deaths are rapidly increasing because of various effects due to the pandemic. In fact, road deaths continued to fall in most of the cities studied during 2020, according to the report, by an average of four percent.

boriquaking

In Sauce We Trust!

Hey guys. Please help my friend out.

Please help me replace my stolen bicycle., organized by Brian Matos

Please help me replace my stolen bicycle., organized by Brian Matos

- 0-20-22

Denver spent $4.1 million to get more people on e-bikes. It worked

Denver launched a rebate program to encourage residents to buy e-bikes and drive less. It’s already wildly popular.

[Source Images: Milatoo/iStock/Getty Images Plus, Acton Crawford/Unsplash]

BY ADELE PETERS

5 MINUTE READ

When Denver started offering a rebate for residents to buy electric bikes, the city thought that the funding would last for three years. Instead, so many people wanted to participate that it was gone in six months.

The first set of 3,000 vouchers—with $400 for a standard rebate, $1,200 for low-income residents, and an extra $500 for anyone buying an electric cargo bike—were claimed within days of the program’s launch last April. Then the city released more vouchers in July, and “they were gone in 22 minutes,” says Grace Rink, the city’s chief climate officer. “We thought it might be popular. We just didn’t know how popular it was going to be.”

To date, 4,156 vouchers, worth a total of more than $4.1 million, have been redeemed at local bike shops. This fall, Rink plans to ask the city council for funding to add more vouchers in 2023.

[Photo: City of Denver]

Denver is aiming to reach net zero emissions as a city by 2040, and cars—a major source of current emissions—are a problem. Car exhaust is also a health issue. “Transportation is the number one source of air pollution in Denver,” Rink says. Supporting e-bikes, which are obviously much cheaper than electric cars, can be a cost-effective way to help shrink both climate pollution and smog.

Unlike some energy-efficiency incentives that give a credit when people pay taxes, the rebate was available at local bike shops as an immediate discount. For low-income residents, the incentive can cover the majority of the cost of some e-bikes. The smaller voucher for other residents “gets people off the fence,” says Rink. “I think what it showed is there were a lot of people who were interested in bikes, but they just needed that little nudge to actually get them into the marketplace.”

Luca Andreu, one Denver resident, hadn’t been considering getting an e-bike, but found out about the city’s voucher program after their car was stolen. Andreu had planned to get a new car after getting the insurance payment but got an e-bike through the program instead, and now uses it to get everywhere. (In Andreu’s case, the voucher covered the entire cost of a cargo bike from Rad Power Bikes, minus taxes and assembly, which they could handle themself.) The electric motor makes it possible to run errands and replace a car more easily than a regular bike.

“I’m an active, athletic person, and there’s absolutely no way I could go the distances that I go now to run errands without the e-bike,” Andreu says. “If you’re super busy, you can’t take half a day to go to PetSmart, for example. With the e-bike, I can get to the grocery store in less than five minutes. With a regular bike, it would probably be 30 minutes, but I don’t always have that energy.”

Another resident, Huong Dang, didn’t own a car before getting an e-bike with the voucher, but says that she took as many as 15 Lyft rides a month before getting it. Over the last four months, she’s taken only three, and biked a total of 856 miles. She had a regular bike before, but like Andreu, found that the electric motor transformed her habits. “Owning and using my e-bike have fundamentally changed my lifestyle,” she says. “I regularly bike 10 miles round trip to Wash park; there were weeks when I did it at least three times a week. I’ve been eating so much better at home because I get excited to bike to the grocery store and load up my two heavy-duty panniers with a ton of food.”

[Photo: City of Denver]

Ride Report, a ride-logging app that some participants chose to download in exchange for a bike shop gift card, found that 90% of recipients are riding at least once a week, and 70% are riding daily. The city also plans to survey voucher users, but already has anecdotal evidence that the program is working. “Folks tell us that they are definitely replacing car trips, and there have also been many people who have told us that they were debating getting a second car for their household, and they got an e-bike instead,” says Rink.

Denver is unusual in that it could easily fund the program; in 2020, local voters passed a 0.25% increase on sales tax to support climate action, which raises around $40 million a year. When the pandemic first began, the city worked with local organizations to set up an e-bike library for low-income workers who couldn’t get to work as bus service was disrupted. They also gave e-bikes to a food rescue organization so it could avoid driving. The new rebate was a logical next step in how to get bikes on the road.

Bike infrastructure in the city has also been improving. “Denver has come a long way in creating a system that makes it accessible for newer [riders] to try biking with an e-bike,” says Noa Banayan, director of federal affairs at the nonprofit PeopleForBikes. The city now has nearly 125 miles of bike lanes, for example, and some are separated from traffic. As more people start to ride, and drivers start expecting to continually see bikes, that can also make riding safer.

The demand for e-bikes may be even greater when gas prices are high. “As gas prices continue to be unstable and higher across the country, a lot of people are looking at replacing car trips with e-bike trips,” says Ash Lovell, electric bicycle policy and campaign director at PeopleForBikes. “I do this a lot going to the grocery store or other places. Most trips that people take are three miles or less from their home, and e-bikes can really kind of close that gap and make it so that you’re not having to pay for gas to go do those daily errands.”

When Vermont launched a smaller e-bike rebate program this summer, it also saw an immediate response. Now, other states are planning to offer similar rebates, including Massachusetts, Connecticut, Hawaii, and Colorado. For a program to really succeed, it should be paired with plans to improve bike lanes, say Banayan and Lovell. It also helps to provide places to charge electric bikes and offer support for more than the bike itself. “A lot of the incentives that we’re seeing come out, especially the ones that are targeted at lower-income Americans, are also giving incentives for things like helmets and bike lights and gloves,” Lovell says.

The same type of program should happen at the federal level, too, bike advocates say. “It should be nationalized, instead of a patchwork framework of states and cities that offer it,” says Banayan. An e-bike tax credit passed the House in the Build Back Better Act last year but was cut from the final Inflation Reduction Act. Now, Banayan says, programs like Denver’s can help gather more evidence that a federal program should happen.