You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

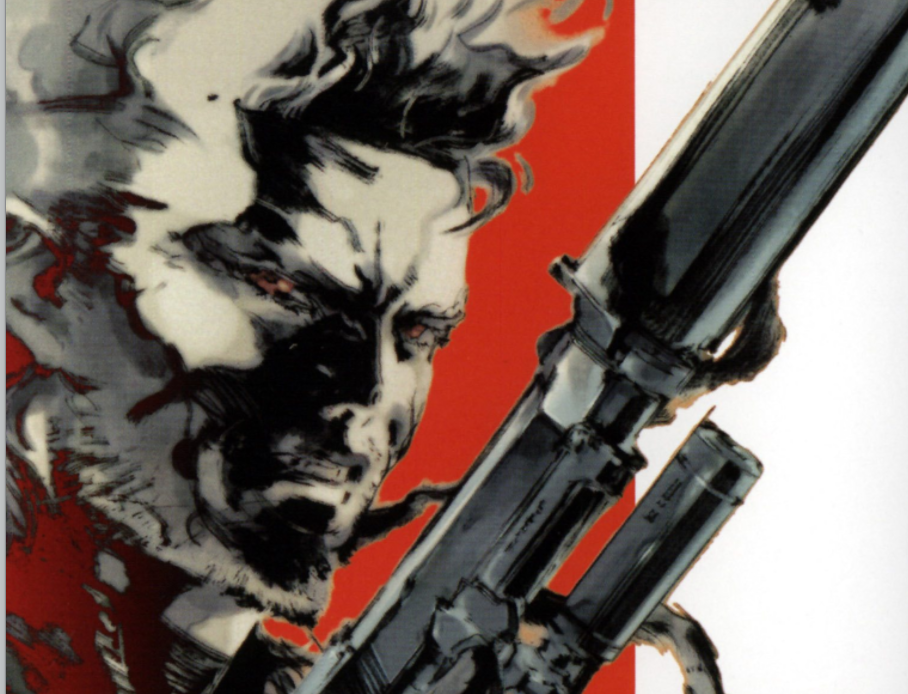

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty looking back..

- Thread starter The Prince of All Saiyans

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?an emissary from hell

I got the bricks from Wakanda

Campbell: "Raiden, turn off the game console off right now  "

"

Me:

I actually turned the game off too

"

"Me:

I actually turned the game off too

Family Man

Banned

Classic. I still play that game from time to time. That game was way ahead of its time.

Campbell: "Raiden, turn off the game console off right now"

Me:

I actually turned the game off too

The Prince of All Saiyans

Formerly Jisoo Stan & @Twitter

Campbell: "Raiden, turn off the game console off right now"

Me:

I actually turned the game off too

The Fukin Prophecy

RIP Champ

Raiden...

That extra feminine looking, neked flipping fakkit single handedly destroyed this game...

Still don't understand what Kojima was thinking with him...

That extra feminine looking, neked flipping fakkit single handedly destroyed this game...

Still don't understand what Kojima was thinking with him...

Apollo Kid

Veteran

The music made this mad creepy playing late at night

oO J Smooth Oo

All Star

one of the best games ever

im a biased mgs stan

im a biased mgs stan

Family Man

Banned

"What we propose to do is not to control content, but to create context. The digital society furthers human flaws and selectively rewards development of convenient half-thruths. Everyone withdraws into their own small gated community, afraid of a larger forum. They stay inside their little ponds leaking whatever "truth" suits them into the growing cesspool of society at large. The different cardinal truths neither clash nor mesh. No one is invalidated, but nobody is right".

MooseMouthMthafuga

Veteran

Classic or nah?

Personally, this was the biggest, most anticipated game of my lifetime.

The hype I had for this game still hasn't been topped.

That trailer blew my mind.I was stark raving mad, having conniptions and shyt

It's a borderline classic, just based on the series overall and the game play.

However the story was ridiculous, and I personally didn't like playing as Raiden.

I remember wondering how much shyt did they smoke while writing the screen play ...and I was like 12 or 13 at the time.

...and I was like 12 or 13 at the time.

It was an amazing experience, but it felt more like a movie than a game breh.

I remember setting the crontroller down and just sitting there with my arms folded, watching 1 hour plus long cut scenes.

The second time I played the game through, I skipped all the cutscenes and felt like I beat the game in 2 hours.

However the story was ridiculous, and I personally didn't like playing as Raiden.

I remember wondering how much shyt did they smoke while writing the screen play

...and I was like 12 or 13 at the time.

...and I was like 12 or 13 at the time.MGS4 gets more hate than it deserves IMO. It plays well and closes the story well.

It has it's flaws like every other MGS game though.

It was an amazing experience, but it felt more like a movie than a game breh.

I remember setting the crontroller down and just sitting there with my arms folded, watching 1 hour plus long cut scenes.

The second time I played the game through, I skipped all the cutscenes and felt like I beat the game in 2 hours.

7th Letter Specialist

We Love Money, We Love Weed!

Classic. Was mad @ first when the realization came that I was going to be him for the rest of the game. After awhile he grew on me tho. I also like that they didnt make him similar to Snake in personality. I felt like his naivety and his "softness" meshed perfectly w/ Snake and the other characters. He was a rookie for Christ Sake! Plus by the end of the story he had matured. Not MGS1 but a solid sequel and I respect the risk they took

Family Man

Banned

There's a reason that, no matter it's flaws, this game is so near and dear to me.

The Scary Political Relevance of 'Metal Gear Solid 2'

The Scary Political Relevance of 'Metal Gear Solid 2'

With a dark political era upon us, the drama of 'Metal Gear Solid 2' feels a little too close to home

By Cameron Kunzelman

Jan 20 2017, 4:00pm

It's a strange thing in retrospect, but two months after the terrorist attack that took down the World Trade Center, we were saving the President from a group of terrorists in Metal Gear Solid 2. Our friend Colonel Campbell explained the mission to us: The terrorists had other hostages, and they were going to blow up an oil spill cleanup facility right off the shore of Manhattan. It was up to us, in the shadow of 9/11, to fight and win against those who would threaten our democracy by paralyzing our financial institutions.

ADVERTISEMENT

To the sadness of many players, we weren't in the body of series protagonist Solid Snake. The character we had taken through Outer Heaven and Shadow Moses, sites of Metal Gear development and staging, had appeared to die in the game's long prologue. Instead, we controlled newcomer Raiden.

Raiden couldn't have been more different from Snake. Long blonde hair instead of a brown mullet, a high-pitched voice instead of a low growl, and an elegant cartwheel move where Snake would have heaved his body forward in a somersault. Gone was the smart and savvy survivalist who had turned his back on the military-industrial complex only to be brought back in for one last mission. Instead, we had an eager recruit who was ready and willing to convert his VR combat training into intimate knowledge of the field.

HEADER AND ALL METAL GEAR SOLID 2 IMAGES COURTESY OF KONAMI

Raiden was wide-eyed and bushy-tailed, and the story of Metal Gear Solid 2 is all about how that enthusiasm is betrayed. As the game pushes forward, we find out that Raiden had real field experience as a child soldier nicknamed Jack the Ripper. We realize that he hasn't been sent into the mission by Colonel Campbell, but instead he was the stooge of a shadowy conspiracy. It's even revealed that the entire plot of the game, from President capture to terroristic threats, is merely a ruse by ex-President George Sears to get access to a list of the names of the people who really run the world.

The real kicker is that those people, the Patriots, have set up the entirety of MGS2 as a simulation. It's meant to test if anyone, you or me or a guy named Jack, could become as good at "tactical espionage action" as the radically awesome Solid Snake. Playing through the game successfully proves these Illuminati-esque figures right: With enough time and effort under the correct conditions, anyone can become a living weapon. Every person in the world can adapt to the container you put them in if you put enough care into the fitting.

ADVERTISEMENT

With enough time and effort under the correct conditions, anyone can become a living weapon

It's the care that matters. You set the narrative or the conditions of possibility just right and you watch people fit into their roles. Debuting just six days before MGS2, the tv show 24 presents the threats of terrorism as explicitly urgent and Middle Eastern. Then it can be used to think through and justify any use case of torture you might want.

Framing Saddam Hussein's actions and speeches in just the right way and ignoring all evidence to the contrary produces consensus on the necessity of a war. It's all conspiratorial, but it is that way because these are acts of grand narrative invention. It's changing the boundaries of how we think about what we think.

When Raiden learns all of this information about himself and the simulation he lives within, he rejects it all. He even begins to suspect that he, his thoughts, or his personality might not be real. It sends him into an existential crisis.

In the long view of retrospect, Metal Gear Solid 2 is a strange light in the darkness. In a country that was slashing civil liberties with the Patriot Act and spinning up into two long wars, it was a breath of fresh air. Through its pageantry and (sometimes) high campiness, it told a very simple story: The people in power probably do not have your best interests in mind. They will shape you and the narratives you interact with to make their positions seem easy and normal, no matter how far afield they are.

ADVERTISEMENT

And it feels like we're coming around to that again. We're heading into a political climate of extreme control, and we will need games like Metal Gear Solid 2 again. Not mobile cash-in games that prevent the President Elect from reaching the inauguration or Tetris clones that obstruct his ability to govern. We need games that reach out to us and say, "Listen, the world is completely upside down, but you're a person and you matter and your beliefs are important."

We're heading into a political climate of extreme control, and we will need games like Metal Gear Solid 2 again

I know how that sounds. How could I position a game about a giant underwater media control system that's being invaded by a cadre of superterrorists who are being foiled by a black-box supersoldier as politically useful in any way?

It's not about the specifics, but about the grand message. As Solid Snake tells Raiden at the end of the game, "Building the future and keeping the past alive are one and the same thing." I think it will be harder that it looks to keep the past alive in the coming years, and despair about the future is already deep-set for many.

The task is, I think, in keeping the thoughts of the past alive. In remembering where we've been and the small gains that have been made for relatively few in the vast cavalcade of violence that we call history.

I hope that those narratives of vague hope and actual political change are remembered so well that the new frameworks of defunding, disrespecting, and trampling over don't completely eradicate them.

ADVERTISEMENT

A game, or a movie, or a piece of music is a document of a moment in time, and Metal Gear Solid 2 came into being in a pre-9/11 world. It had the political ideology of a game out of time, from a different era, or from a parallel universe. And that's why it is still so affecting to me today: It has the spirit of art that said "no" to its time.

I hope that game developers, from blockbusters to sub-indie hobby projects, keep that spirit alive. I hope the slow, painful progress of the last few years can be saved. I hope that those narrative of vague hope and actual political change are remembered so well that the new frameworks of defunding, disrespecting, and trampling over don't completely eradicate them. The next several years are going to require games that are out of their time, because we're going to need ways to point to the world we want to have.

The Scary Political Relevance of 'Metal Gear Solid 2'

The Scary Political Relevance of 'Metal Gear Solid 2'

With a dark political era upon us, the drama of 'Metal Gear Solid 2' feels a little too close to home

By Cameron Kunzelman

Jan 20 2017, 4:00pm

It's a strange thing in retrospect, but two months after the terrorist attack that took down the World Trade Center, we were saving the President from a group of terrorists in Metal Gear Solid 2. Our friend Colonel Campbell explained the mission to us: The terrorists had other hostages, and they were going to blow up an oil spill cleanup facility right off the shore of Manhattan. It was up to us, in the shadow of 9/11, to fight and win against those who would threaten our democracy by paralyzing our financial institutions.

ADVERTISEMENT

To the sadness of many players, we weren't in the body of series protagonist Solid Snake. The character we had taken through Outer Heaven and Shadow Moses, sites of Metal Gear development and staging, had appeared to die in the game's long prologue. Instead, we controlled newcomer Raiden.

Raiden couldn't have been more different from Snake. Long blonde hair instead of a brown mullet, a high-pitched voice instead of a low growl, and an elegant cartwheel move where Snake would have heaved his body forward in a somersault. Gone was the smart and savvy survivalist who had turned his back on the military-industrial complex only to be brought back in for one last mission. Instead, we had an eager recruit who was ready and willing to convert his VR combat training into intimate knowledge of the field.

HEADER AND ALL METAL GEAR SOLID 2 IMAGES COURTESY OF KONAMI

Raiden was wide-eyed and bushy-tailed, and the story of Metal Gear Solid 2 is all about how that enthusiasm is betrayed. As the game pushes forward, we find out that Raiden had real field experience as a child soldier nicknamed Jack the Ripper. We realize that he hasn't been sent into the mission by Colonel Campbell, but instead he was the stooge of a shadowy conspiracy. It's even revealed that the entire plot of the game, from President capture to terroristic threats, is merely a ruse by ex-President George Sears to get access to a list of the names of the people who really run the world.

The real kicker is that those people, the Patriots, have set up the entirety of MGS2 as a simulation. It's meant to test if anyone, you or me or a guy named Jack, could become as good at "tactical espionage action" as the radically awesome Solid Snake. Playing through the game successfully proves these Illuminati-esque figures right: With enough time and effort under the correct conditions, anyone can become a living weapon. Every person in the world can adapt to the container you put them in if you put enough care into the fitting.

ADVERTISEMENT

With enough time and effort under the correct conditions, anyone can become a living weapon

It's the care that matters. You set the narrative or the conditions of possibility just right and you watch people fit into their roles. Debuting just six days before MGS2, the tv show 24 presents the threats of terrorism as explicitly urgent and Middle Eastern. Then it can be used to think through and justify any use case of torture you might want.

Framing Saddam Hussein's actions and speeches in just the right way and ignoring all evidence to the contrary produces consensus on the necessity of a war. It's all conspiratorial, but it is that way because these are acts of grand narrative invention. It's changing the boundaries of how we think about what we think.

When Raiden learns all of this information about himself and the simulation he lives within, he rejects it all. He even begins to suspect that he, his thoughts, or his personality might not be real. It sends him into an existential crisis.

In the long view of retrospect, Metal Gear Solid 2 is a strange light in the darkness. In a country that was slashing civil liberties with the Patriot Act and spinning up into two long wars, it was a breath of fresh air. Through its pageantry and (sometimes) high campiness, it told a very simple story: The people in power probably do not have your best interests in mind. They will shape you and the narratives you interact with to make their positions seem easy and normal, no matter how far afield they are.

ADVERTISEMENT

And it feels like we're coming around to that again. We're heading into a political climate of extreme control, and we will need games like Metal Gear Solid 2 again. Not mobile cash-in games that prevent the President Elect from reaching the inauguration or Tetris clones that obstruct his ability to govern. We need games that reach out to us and say, "Listen, the world is completely upside down, but you're a person and you matter and your beliefs are important."

We're heading into a political climate of extreme control, and we will need games like Metal Gear Solid 2 again

I know how that sounds. How could I position a game about a giant underwater media control system that's being invaded by a cadre of superterrorists who are being foiled by a black-box supersoldier as politically useful in any way?

It's not about the specifics, but about the grand message. As Solid Snake tells Raiden at the end of the game, "Building the future and keeping the past alive are one and the same thing." I think it will be harder that it looks to keep the past alive in the coming years, and despair about the future is already deep-set for many.

The task is, I think, in keeping the thoughts of the past alive. In remembering where we've been and the small gains that have been made for relatively few in the vast cavalcade of violence that we call history.

I hope that those narratives of vague hope and actual political change are remembered so well that the new frameworks of defunding, disrespecting, and trampling over don't completely eradicate them.

ADVERTISEMENT

A game, or a movie, or a piece of music is a document of a moment in time, and Metal Gear Solid 2 came into being in a pre-9/11 world. It had the political ideology of a game out of time, from a different era, or from a parallel universe. And that's why it is still so affecting to me today: It has the spirit of art that said "no" to its time.

I hope that game developers, from blockbusters to sub-indie hobby projects, keep that spirit alive. I hope the slow, painful progress of the last few years can be saved. I hope that those narrative of vague hope and actual political change are remembered so well that the new frameworks of defunding, disrespecting, and trampling over don't completely eradicate them. The next several years are going to require games that are out of their time, because we're going to need ways to point to the world we want to have.

Many people disliked the game but it is a classic to me