After a news conference on Aug. 6, 2012, community members in Oak Creek, Wisc., hold up a mug shot of Wade Michael Page, an Army veteran and the suspected shooter in a deadly attack on a Sikh temple.

Photo: Darren Hauck/Getty Images

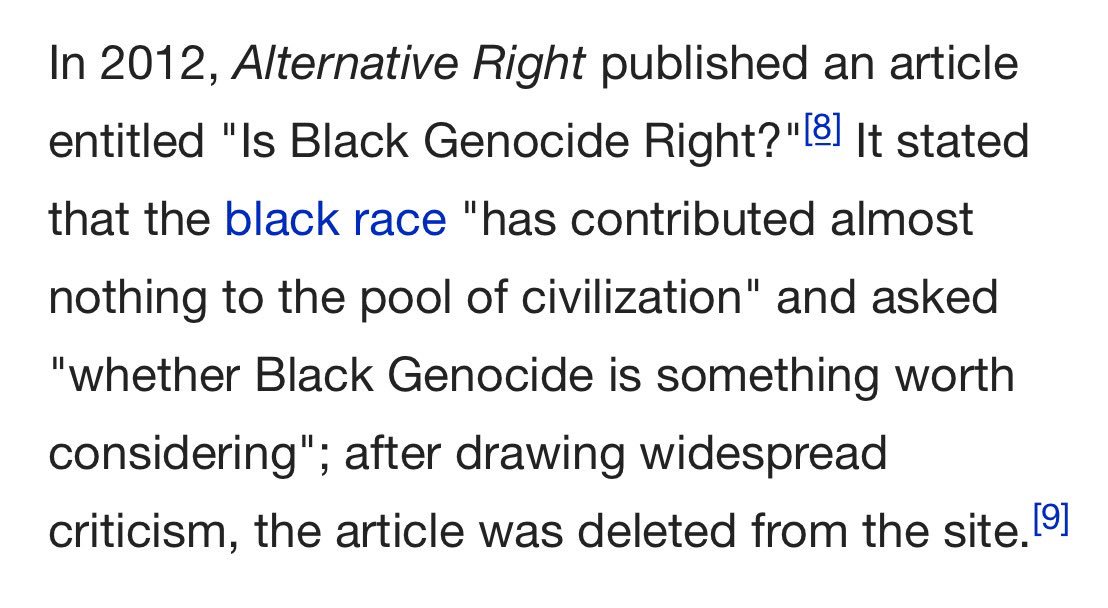

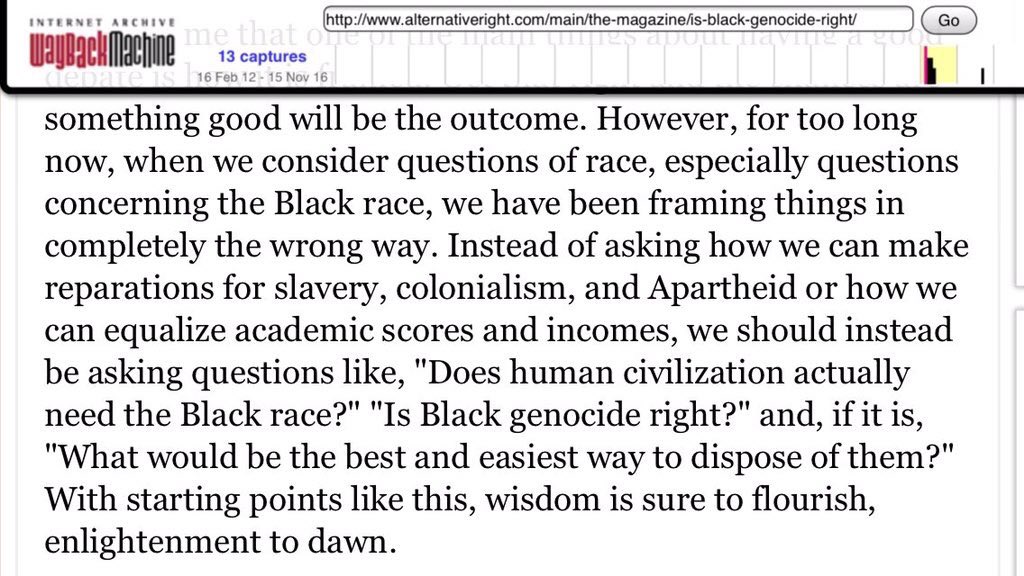

R

eforming police, as it turns out, is a lot harder than reforming the military, because of the decentralized way in which the thousands of police departments across the country operate, the historical affinity of certain police departments with the same racial ideologies espoused by extremists, and an even broader reluctance to do much about it.

“If you look at the history of law enforcement in the United States, it is a history of white supremacy, to put it bluntly,” said Simi, citing the origin of U.S. policing in the slave patrols of the 18th and 19th centuries. “More recently, just going back 50 years, law enforcement, particularly in the South, was filled with Klan members.”

Norm Stamper, a former chief of the Seattle Police Department and vocal advocate for police reform, told The Intercept that white supremacy was not simply a matter of history. “There are police agencies throughout the South and beyond that come from that tradition,” he said. “To think that that kind of thinking has dissolved somehow is myopic at best.”

Stamper said he had fired officers who expressed racist views, but added, “It’s not likely to happen in most police departments, because many of those departments come from a tradition of saying the officer is entitled to his or her opinions.” Whether the First Amendment protects an officer’s right to express racist, white supremacist views — or even to associate with organizations that endorse those views — is something that remains a subject of debate, Stamper said. “You can fire someone. Whether the termination will stand up under review is the real question.”

“Local, state, federal agencies, all to some extent have their hands tied, because it’s not necessarily against the law to be a member of a domestic hate group” said Simi, noting the military as the one exception because of its unique legal status. For instance, the U.S. government considers the KKK a hate group — but membership in the group is not illegal. That’s the case for all domestic hate or extremist groups, though authorities can choose to target their members under conspiracy statutes, Simi said.

Most police departments don’t screen prospective officers for hate group affiliation. The SPLC has reported that the number of these groups

peaked at more than 1,000in 2011, from less than half that in the late 1990s, though experts like Simi note that many of these groups “come and go” and membership between them is often fluid.

Although officers have been fired for expressing hateful views — sometimes to be re-hired by other departments, as happens regularly with officers accused of misconduct — some officers have also challenged those dismissals in court. Robert Henderson, an 18-year veteran of the Nebraska State Patrol, was

fired when his membership in the Klan was discovered. He sued on First Amendment grounds and appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear his case. Last year, 14 officers in the San Francisco Police Department were caught exchanging racist and homophobic texts that included several references to “white power” and messages such as “all ******s must fukking hang.” Most of those officers remain on the force after an attempt to fire several of them

was blocked by a judge, who said the statute of limitation had expired.

“All agencies, if they want to, can curtail this problem — the problem is that many do not,” said Jones, who has been tracking similar incidents following the 2006 FBI report and believes many more get buried behind the code of silence that often dominates police departments. “When somebody holds a belief that indicates that they do not see all Americans are worthy of equal protection under the law, it compromises their ability to be a police officer.”

A member of the Georgia Security Forces, an extremist militia, participates in a military drill in Flovilla, Ga., on Nov. 12, 2016.

Photo: Mohammed Elshamy/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

A

ccording to the Counterterrorism Policy Guide, the FBI has the option to mark a watchlisted police officer as a “silent hit,” thus preventing queries to the National Crime Information Center, a clearinghouse for crime data accessible to law enforcement agencies nationwide, from returning a record that identifies the officer as having been flagged as a known or suspected terrorist. The document states that a “specific, narrowly defined, and legitimate operational justification” must be given in order to mark a KST’s entry as a silent hit. The suspect’s membership or affiliation with a law enforcement or military agency with access to the NCIC database is one of the specific justifications listed, implying that extremist infiltration is enough of a concern that the FBI has built-in protocols to prevent domestic terrorism investigations from being obstructed by members of law enforcement.

The FBI document also notes that in order to protect the safety of local law enforcement, suspects who are “violent or are known to be armed and dangerous” may not be marked as silent hits. It’s unclear how that standard applies to armed law enforcement personnel, especially since the FBI document singles out not only white supremacist groups for their ties to law enforcement, but also militia extremists and sovereign citizen extremists. While there is plenty of overlap between them, the last group, in particular, is characterized by deep anti-government ideology and the belief that “even though they physically reside in this country, they are separate or ‘sovereign’ from the United States,” the FBI notes

on its website. “As a result, they believe they don’t have to answer to any government authority, including courts, taxing entities, motor vehicle departments, or law enforcement.”

In a 2011 article, the FBI’s counterterrorism analysis section called

sovereign citizens“a growing domestic threat to law enforcement.” In one 2010 incident, two Arkansas police officers were killed when 16-year-old sovereign citizen Joseph Kane fired on them with an AK-47 assault rifle after he and his father were pulled over for a routine stop.

A

2014 survey found that sovereign citizen extremists were perceived by law enforcement agencies as a top threat, ahead of foreign-inspired extremists. And a

2015 DHS intelligence assessment, written in coordination with the FBI, warned about the continuing threat sovereign citizen extremists pose to police officers.

The counterterrorism guide does not specify the conditions under which the FBI will notify local law enforcement agencies whose members may be under surveillance as silent hits. Michael German, a former FBI agent who specialized in domestic terrorism investigations, told The Intercept that such alerts are likely handled on a “case-by-case basis.” “Typically, if someone in the police department is suspect, unless it’s an extreme case of leadership, professional courtesy requires some sort of notification,” he said.

The FBI did not respond to a detailed series of questions sent by The Intercept about its knowledge of extremists’ presence in law enforcement agencies, but a spokesperson for the agency did comment on the practice of placing silent hits on law enforcement officers. “While a silent hit would keep a subject who is a law enforcement employee from knowing they are under scrutiny, it would be standard practice to let someone at the agency know that one of their officers was under investigation,” the spokesperson said.

A

lthough the FBI’s counterterrorism guide prohibits watchlisting individuals in the Known or Suspected Terrorist File “based solely on activities protected by the First Amendment,” the document does not elaborate on what would constitute such activity. Nor does it state what specific actions on the part of officers would be serious enough to warrant inclusion in the watchlist. The document refers to the Terrorist Screening Center’s March 2013

Watchlisting Guidance, previously published by

The Intercept, for additional details regarding the watchlisting standard. The FBI did not answer questions about what activities would warrant entry into the list.

Civil rights groups have denounced the Known or Suspected Terrorist database’s lack of transparency and the vague formulation of its standards. In a detailed

analysis of the KST watchlist based on documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, the ACLU observed that the goal of the list “is not law enforcement, but the surveillance and tracking of individuals for indefinite periods.” The April 2016 report characterized the watchlist as “essentially a black box — an opaque and expanding accumulation of names.”

A disproportionate number of Muslims have been included on the watchlist, and because the database is accessible to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies nationwide, the ACLU said, they are exposed to “unwarranted scrutiny or investigation by police.” That level of scrutiny has hardly been applied to white supremacists, however, even though the country’s

first anti-terrorism laws, in the 1870s, were aimed at protecting black citizens from groups like the KKK, and despite the ongoing threat posed by these extremists.

“This is a fundamental problem in this country: We simply do not take this flexible, and forgiving, and exceptionally understanding approach for combating any other form of terrorism,” said Jones. “Anybody who’s on social media advocating support for ISIS can be criminally charged with very little effort.”

“For some reason, we have stepped away from the threat of domestic terrorism and right-wing extremism,” Jones continued. “The only way we can reconcile this kind of behavior is if we accept the possibility that the ideology that permeates white nationalists and white supremacists is something that many in our federal and law enforcement communities understand and may be in sympathy with.”

That sympathy might just be reflected by the election of a president who was endorsed and celebrated by the KKK, and who has been reluctant to disassociate himself from individuals espousing white supremacist views.

“This election, for white supremacists, was a signal that ‘We’re on the right track,’” said Simi. “I have never seen anything like it among white supremacists, where they express this feeling of triumph and jubilee. They are just elated about the idea that they feel like they have somebody in the White House who gets it.”

Top photo: A member of the Ku Klux Klan protests the removal of the Confederate flag from the state house building in Columbia, S.C., on July 18, 2015.

for evidence and information on white supremacist terrorism

for evidence and information on white supremacist terrorism