You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Iran retaliates against Israel with 100s of drones, cruise, ballistic missiles for striking their Embassy (4/13) BREAKING: Israel strikes Iran (4/18)

- Thread starter Arithmetic

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?IIVI

Superstar

Then Iran and the Middle East result to biological warfare on our troops and Pakistan nuclear threat to allies.If it came to that, the US would probs just resort to chemical warefare and millions of ai powered death drones

This is why it can't escalate and we can't ride with Israel.

Even conservative/middle political isle don't want to see us go on the offensive.

It's a sad day when I see online Conservatives have more common sense than Coli Liberals. We've got to be smart.

We'll still win, but many of our troops will die, our military resources would be more spent and America will go full Republican which internally will screw 90+% of the American people over for generations to come.

Yet what do we get out of it?

We're fighting for what to our benefit over there?

Nothing. fukking nothing.

We used American lives to protect a flaky "ally" for starting a mess. Terrific.

Middle East will be the Middle East.

It's time to move out of there and focus on more mutually beneficial, composed and honestly vastly more intelligent areas of the world.

Asia is much more important to U.S. interests than the Middle East

We need to prioritize, and our priorities should be clear.

In this world of proliferating conflicts, the United States no longer has the power or the money to handle everything at once. We are no longer a hyperpower or a global hegemon. But retreating into a shell of isolationism and letting the world burn, as the MAGA faction of the Republican Party would have us do, is also not an option. The U.S. economy depends critically on other nations’ products, and this will always be true; but even if it weren’t the case, abandoning the world to a bloc of totalitarian powers would ultimately put the U.S. itself in grave danger. This was the basic point made in the Roosevelt Administration’s Why We Fight film series, and it remains true today. Oceans are not an insurmountable barrier; a Eurasia dominated by China, Russia, and Iran would eventually force the U.S. to its knees through a combination of economic sanctions and military threats.

Because the U.S. is no longer a hyperpower and can no longer do everything everywhere all at once, though, we have to prioritize where to send our money, weapons, and — perhaps most importantly — our diplomatic attention. Right now, the two regions with active conflicts are Europe and the Middle East, and so our resources are going there instead of to Asia. In fact, Biden has been taking a softer approach toward China in 2023 than in the first two years of his presidency; part of this is probably because China’s economic woes make it seem like less of an imminent threat, but part of it is must be due to the fact that the wars in Ukraine and now Israel are absorbing U.S. attention and effort.

But whether or not that tentative detente is a good idea or a mistake, an overall shift in focus away from Asia would definitely be a miscalculation. Regardless of how hawkish the U.S. wants to be toward China, it makes sense to be investing more diplomatic energy and military preparation into the region. In particular, the urge to plunge back into Middle Eastern conflict should be strongly resisted. This is both because Asia is a more strategically important region, and because American power is more suited to producing a more positive outcome in Asia than in the Middle East.

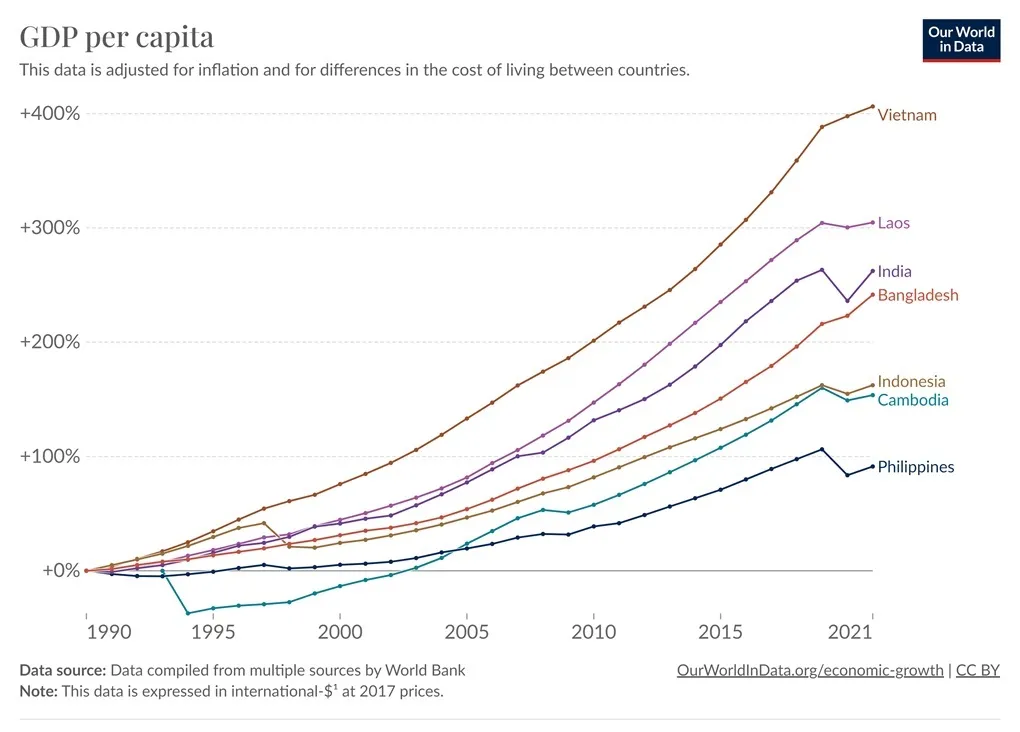

And thanks to the rapid growth in South and Southeast Asia, the region’s importance to the U.S. economy is only set to grow — even if we keep decoupling from China.

The Middle East, meanwhile, is absolutely tiny as a trading partner. In particular, the U.S. isn’t dependent on Mideast oil at all. Thanks to fracking, we are a net exporter of crude. Saudi Arabia and UAE and Kuwait could get eaten by Godzilla and our oil refineries would just keep humming. (By the way, U.S. oil production just hit a new record under Biden.)

Now, it’s true that some of our allies, like Japan and South Korea, do still buy quite a bit of Middle Eastern oil. And if there were big disruptions to Middle Eastern oil supply, global prices would rise a lot, causing a windfall for U.S. oil producers but hurting other types of U.S. business. But thanks to the rise of electric vehicles, oil is becoming less important to the global economy by the day. Total oil consumption is forecast to flatline soon.

Mideast conflicts that raise the price of oil relative to electric vehicles and other substitutes will only accelerate this trend.

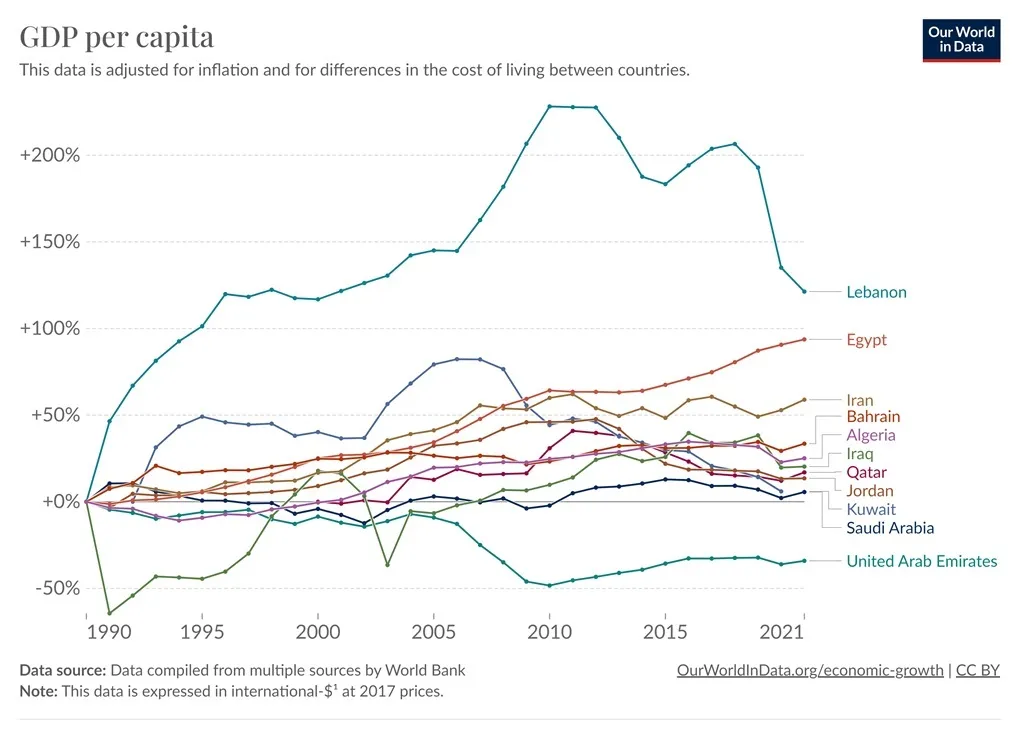

The Middle East is therefore rapidly diminishing in economic importance to the U.S., even as Asia continues to become more crucial. Cutting the U.S. off from the Asian economic supercluster would deeply wound our nation’s prosperity, while there’s really not a lot we need from the Middle East anymore.

The U.S. should therefore continue to maintain as light a presence in the Middle East as possible. This doesn’t mean we should withdraw completely. There are extreme cases where judicious, targeted applications of American power can prevent some of the catastrophes that regularly plague the region — protecting the Syrian Kurds from genocide, restraining Israel’s brutality toward the Palestinians, or helping Israel protect itself from wholesale destruction by Iran and its proxies. But these should always be done with a minimum of force and money and attention, and always with an eye toward withdrawing again.

In Asia, meanwhile, the U.S. should be beefing up both our defensive power and our engagement with other countries. We need to accelerate the supply of defensive weapons to Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, India, and the Philippines, and to keep building and strengthening and expanding multilateral organizations like the Quad. We need to re-engage economically by re-joining the modified TPP, and by creating a dense network of other economic agreements in Asia. And in general, we just need to pay a lot of attention to the region, making sure our allies and quasi-allies and potential allies know we’re there for the long haul, and won’t suddenly withdraw to go plunge into some foolish conflict in the Middle East.

It will take a lot of discipline and a lot of explanation from the Biden administration and its successors to keep pivoting to Asia even in the face of the Israel-Gaza war and other divisive, emotional, headline-grabbing conflicts. But we have to do it anyway.

Instead of investing here:

We're investing more here:

What are we doing here? Make it make sense.

Not to mention it's been more expensive for us due to the lives we lost being involved in the Middle East from the 1990's.

This has been expensive for jack shyt.

It's time for the future. Leave this place be.

Not to mention our troops would probably be vibing way more stationed in the Pacific than they would in the Middle Eastern desert and their families more relieved.

Last edited:

I told yall. Add China in there too and North Korea wants a piece of some ass cheeks. Only Trump can stop this.

we aint making it to GTA 6

Last edited:

Whites and jews ain't gonna end the world... but when their time is finally up

the world will definitely be in bad shape

I hope not because whites and white jews are destroying it, and have been destroying it for a very very long time

I Really Mean It

Veteran

stop posting links from the spectator. it’s barely removed from the daily mail in terms of contrarian sensationalism and accuracy. it’s also a far right rag.

They’re quoting the Washington Post.stop posting links from the spectator. it’s barely removed from the daily mail in terms of contrarian sensationalism and accuracy. it’s also a far right rag.

Mister Terrific

It’s in the name

Pull Up the Roots

Breakfast for dinner.

^ It's like some of you dudes want shyt to escalate to the point of no return. It's freaking stupid.

Neo. The Only. The One.

THE ONE

^ It's like some of you dudes want shyt to escalate to the point of no return. It's freaking stupid.

You see it.

It really isn't. #14 in the world and a live threat to our troops:

2025 Military Strength Ranking

Ranking the nations of the world based on current available firepower.www.globalfirepower.com

Israel is #17

Ukraine #18

Germany #19

It'll be a hard take down for the U.S with casualties on our side as carriers and bases would be taking hits from hyper sonics.

Biden support would be obliterated. If you want to avoid Republican leadership for maybe the next ~2-3 decades, you do not want war with Iran.

Americans hate war because we hate seeing our soldiers not make it back. It's how Nixon was elected not too long after the adored JFK. If we get into a war with Iran, our troops will be dying for Israeli's right in front of a voting crowd.

Do the math.

they got Russia at number 2..... that's all I need to see to know is about some bullshyt. Iran will get washed. Bomb their bases kill the leaders let the people rise up. Bam instant ally. Plus all the Persian PAPGs you can handle. New lane for passport bros.

they got Russia at number 2..... that's all I need to see to know is about some bullshyt. Iran will get washed. Bomb their bases kill the leaders let the people rise up. Bam instant ally. Plus all the Persian PAPGs you can handle. New lane for passport bros.

If Trump is president he loses nothing.

His Healthcare won't be cut

Police won't lynch him in public

People he knows personally won't be targeted by armed magats

This is just Monday night football for him. The stakes are his team losing and him having to retire without any rings or trophy.

If you're a woman that means the right to do whatever to your body can be challenged with abortion and then soon all birth control outlawed.

If you're a black person, a Trump presidency means increased police budgets so they can murder you and everyone who looks like you.

If you're a senior looking forward to retirement, a Trump presidency means a cut in Medicare funding and higher drug prices because his buddies at big pharma want to grow their profits.

If you're anyone who has been wronged by Amazon or any megacorp, it means the budget of the FTC gets slashed so your hopes for justice go down even lower.

A Trump presidency affects actual working people, white millionaires like Nancy Pelosi and Biden are moving this way because they would be completely spared from the horrible policies that Trump would put into place. They don't have to worry about schools losing funding because their children are adults and their grand kids are going to prestigious private schools. They don't have to care about Medicare because they access the best medical care in the world and would pay without any issue since they are literally millionaires. They won't have to worry about student loans, and they wont even have to worry about climate change or nuclear war since they have their luxury bunkers they can hide in. This is nothing but a game to them and when you understand that, their baffling decisions suddenly start making more sense. If people who were elected were flat out banned from trading stocks and had to work actual jobs in retail, trades, medicine, education and got a salary that didn't exceed the average teacher, they'd actually care about this shyt because they'd be affected by these policies.

I agree with all of this

unfortunately I think Trump will be re-elected

I'm not being dramatic, but the domino effect of Israel being aggressive I wouldn't be surprised if it turns out to be World War 3

and as far as America goes, Black Americans are going to be f*cked if Trump is re-elected

Mister Terrific

It’s in the name

they got Russia at number 2..... that's all I need to see to know is about some bullshyt. Iran will get washed. Bomb their bases kill the leaders let the people rise up. Bam instant ally. Plus all the Persian PAPGs you can handle. New lane for passport bros.

levitate

I love you, you know.

IIVI

Superstar

It's just wasteful, America being so caught up in the Middle East is maybe the worst investment anyone is making on this planet.

Straight up a money suck that's going nowhere and it's value will only go down from here the longer we stay there.

Worse than some of these people caught up in ponzischemes

Countries who invest in Asia will get the W.

Straight up a money suck that's going nowhere and it's value will only go down from here the longer we stay there.

Worse than some of these people caught up in ponzischemes

Countries who invest in Asia will get the W.

Last edited:

Amare's Right Hook

Southeast World Champion

Gaza stands with Diddy