Justice sought for hanging of black soldiers after 1917 Houston riots

- By DeNeen L. Brown | The Washington Post

- Aug 24, 2017

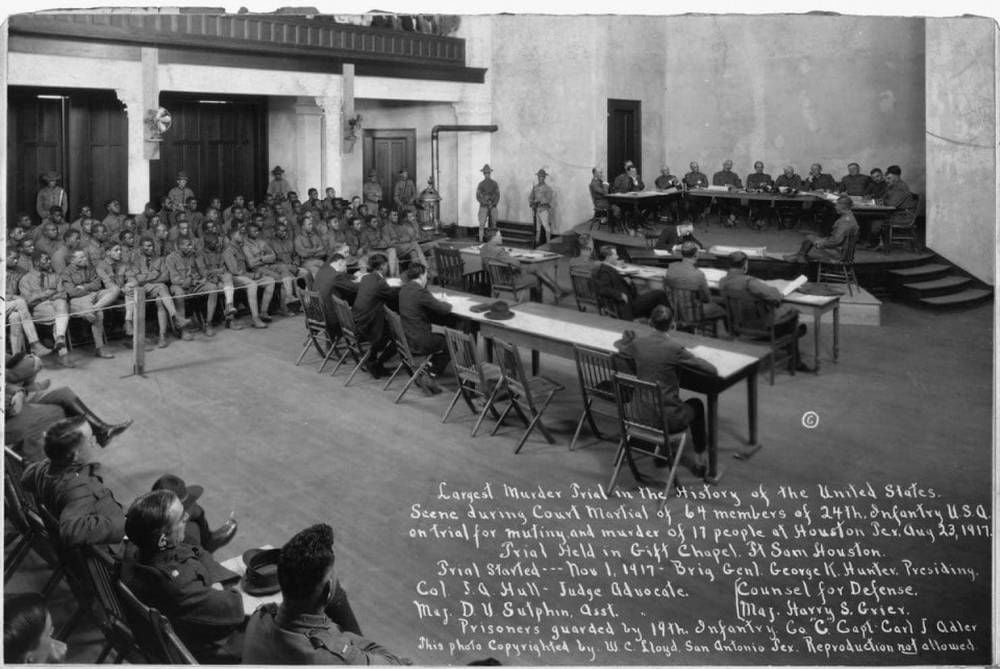

A scene from the court-martial of 63 members of the all-black 24th Infantry on trial for mutiny and murder of 17 people in Houston on Aug. 23, 1917. At the time, it was the largest murder trial in U.S. history. W.C. Lloyd via The Washington Post

[...] One hundred years later, the descendants of three of the hanged men — William Nesbit, Thomas Coleman Hawkins, and Jesse Ball Moore — have petitioned the U.S. government for posthumous pardons, arguing they “suffered grave injustices at the hands of the United States when they were executed by hanging after a defective trial by court-martial.”

The petitions were filed with the Justice Department in October, near the end of President Barack Obama’s presidency. In March, officials responded that the Justice Department does not handle posthumous pardons. The petitions were sent to the Trump White House earlier this year. The families are still awaiting a response.

“It’s important for them to be pardoned because they did not get due process in the beginning,” said Angela Holder, the great-niece of Jesse Ball Moore and a history professor at Houston Community College. “They should have been allowed to petition for clemency.”

Frederic Borch III, the regimental historian for the JAG Corps, suggested Holder and other descendants seek the pardon.

“No black soldier was going to get a break in the Jim Crow Army of 1917,” said Borch, a retired colonel who was the first prosecutor of terrorists at Guantanamo Bay. “Were they guilty? Some were. Were some also innocent? Highly likely. But you can’t discern the truth and get a fair trial when you have one defense counsel representing 63 defendants.”

“While everything about the court-martial was legal,” Borch said, “it was not fair. Not a fair trial then. Certainly, not a fair trial now.”

The 3rd Battalion of the 24th United States Infantry — a unit of the famed Buffalo Soldiers — had been deployed from New Mexico to Texas to guard construction at Camp Logan, a base being built shortly after the United States entered World War I.

In Houston, the sight of black men wearing uniforms and carrying guns incensed white residents. The soldiers were angered by the “Whites Only” signs in Houston and street car conductors demanding they sit in the rear. They hated being called the N-word by white Houstonians.

The incident that sparked the riots on Aug. 23, 1917, began when white Houston police officers burst into the home of a black woman, assaulting her and pulling her — dressed only in her nightgown — into the street as her five children looked on. When a black soldier, Army Pvt. Alonzso Edwards, came to the woman’s rescue, he was pistol-whipped by a white officer and then arrested, according to the Texas Historical Commission.

Cpl. Charles Baltimore, one of the most respected soldiers in the regiment, went to the police station to check on Edwards. While there, Baltimore was beaten by police, shot and arrested. He was later released. But by then, false reports had reached the black soldiers’ camp that Cpl. Baltimore had been killed. That’s when 156 black soldiers of the Third Battalion defied orders to stay in the base and marched to Houston armed with rifles and ammunition.

When the soldiers reached the city, the black soldiers fought Houston police and local citizens in gun battles. Five white police officers were among those killed. The next day, martial law was declared in Houston.

In Houston, 63 black soldiers were charged with disobeying orders, mutiny, murder and aggravated assault. The soldiers all pleaded not guilty and were defended by a single man, Maj. Harry S. Grier, who taught law at West Point, but was not a lawyer and had no trial experience.

Though 169 witnesses testified for the prosecution during the 22-day court-martial, many could not identify the defendants because the riots unfolded at night during heavy rain.

Yet on Nov. 28, 1917, 13 black soldiers were sentenced to be hanged. Forty-one black soldiers were given life sentences. Four were given lesser sentences. Five were acquitted. And, two more court-martials were held to try other soldiers.

The men being sent to the gallows were ordered to write letters to their families.

“Dear Mother and Father,” wrote Thomas C. Hawkins, a private first class, “When this letter reaches you I will be beyond the veil of sorrow. I will be in heaven with the angels. I am sentenced to be hanged for the trouble that happened in Houston, Texas. Altho I am not guilty of the crime that I am accused of, but mother, it is God’s will that I go now and in this way.”

A white soldier from Company C of the 19th Infantry, later described the gruesome hanging this way:

“The doomed men were taken off the trucks, not one making the slightest attempt to resist,” the white soldier wrote. “They were shivering a little, but I think this was due more to the cold rather than fear. The unlucky thirteen were lined up. The conductors took their places and the men for the last time heard the command, ‘March.’ Thirteen ropes dangled from the crossbeam of the scaffold, a chair in front of ever rope, six on one side, seven on the other. As the ropes were being fastened about the mens’ necks, big [Pvt. Frank] Johnson’s voice suddenly broke into a hymn, ‘Lord, I’m comin’ home.’ And the others joined him. The eyes of even the hardest of us were wet.”

The hangings of the black soldiers — without a chance for appeal — provoked outrage around the country. The New York chapter of the NAACP petitioned President Woodrow Wilson for clemency.

In the aftermath, the War Department issued a ruling that “all death sentences be suspended until the President of the United States could review all records.” Wilson would eventually commute the sentences of 10 black soldiers. And the military reformed the court-martial process, establishing an appeals court.

“The silver lining in this tragedy is that some Army lawyers realized that courts-martial had to be more like courts — there had to be some sort of appellate process where an accused could have his conviction reviewed for legal sufficiency,” Borch said. “As a result of the Houston riots courts-martial, the Army recognized that the lack of an appellate structure was not fair. So it created boards of review that began doing legal reviews of serious cases. This was the beginning of the ‘judicialization’ of courts-martial that continued for the next 75 years.”

Justice sought for hanging of black soldiers after 1917 Houston riots