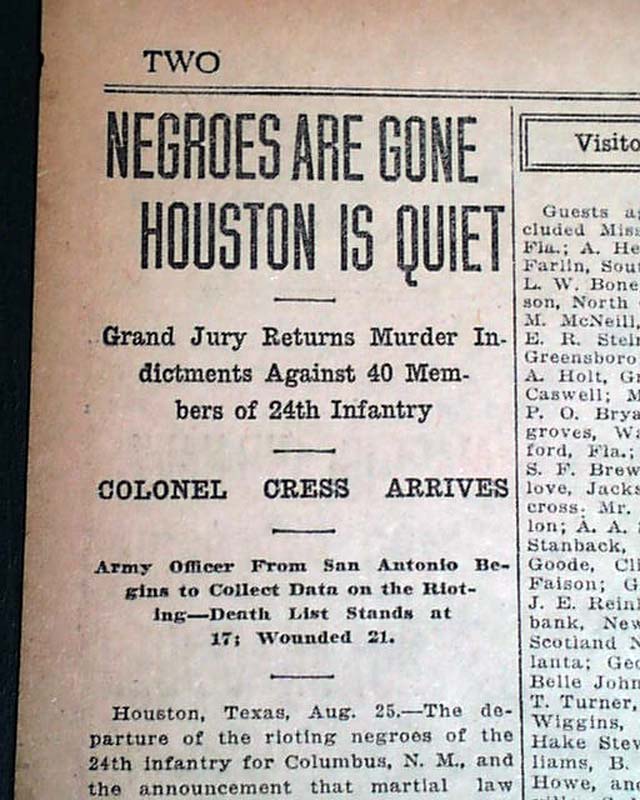

Martial law was declared in Houston, and the Third Battalion was not only returned to Columbus, New Mexico, but the entire regiment was later transferred to the Philippines. Seven of its soldiers agreed to testify in exchange for clemency.

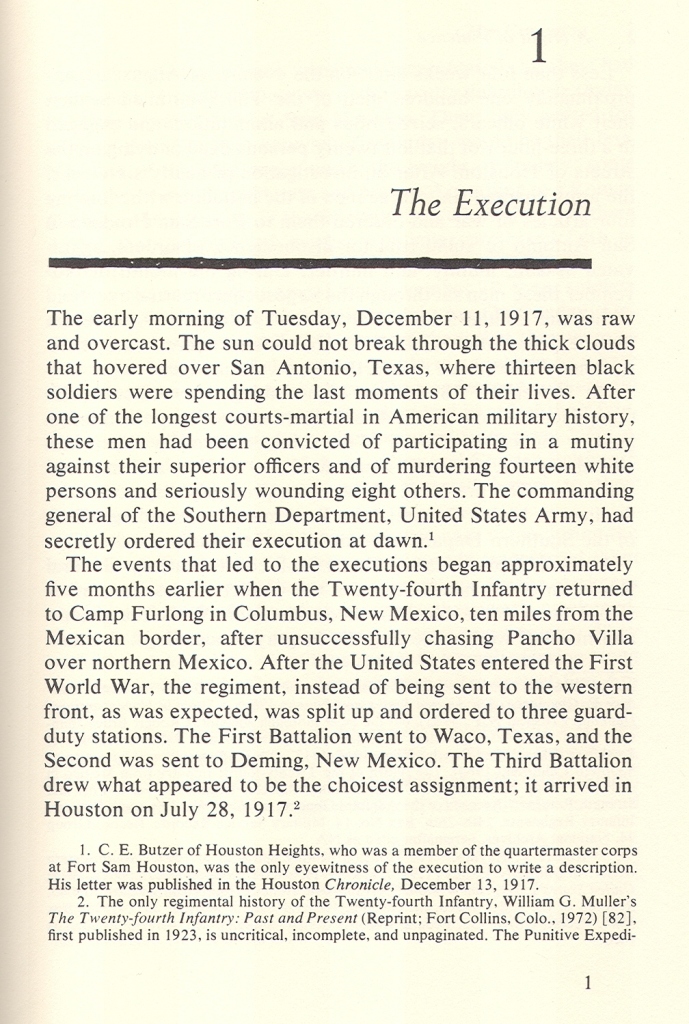

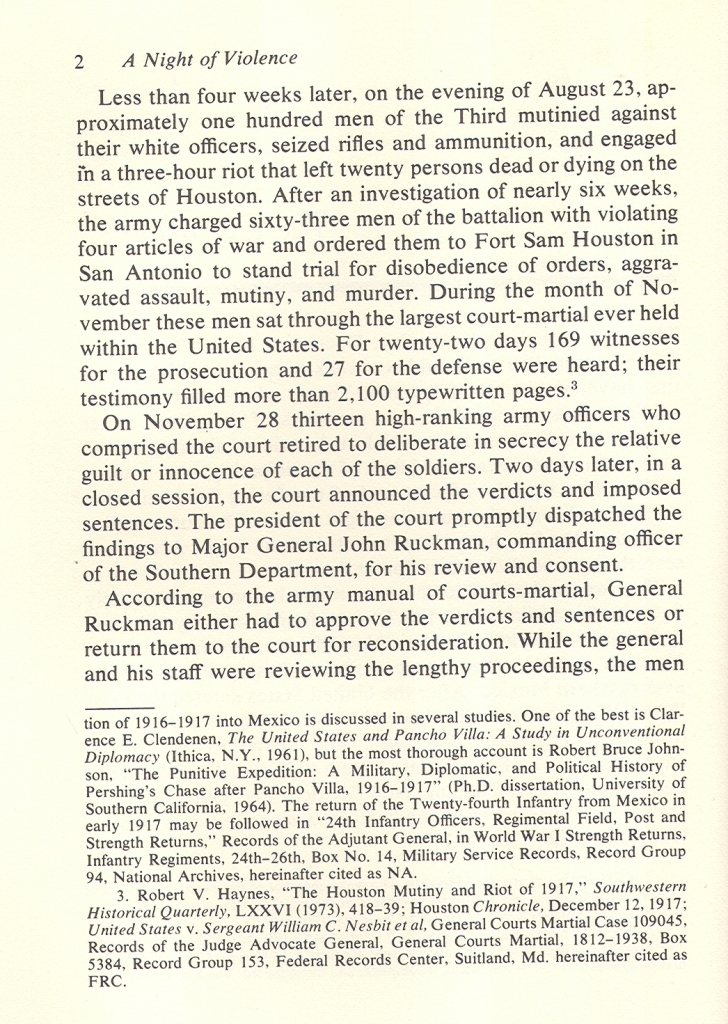

Almost two hundred witnesses testified over twenty-two days, and the transcripts of the testimony covered more than two thousand pages. Author Robert V.

H

aynes suggests that General John Wilson Ruckman was “especially anxious for the courts-martial to begin”.[4]:251 Ruckman had preferred the proceedings take place in El Paso, but eventually agreed to allow them to remain in San Antonio. Haynes feels the decision was made to accommodate the witnesses who lived in Houston, plus “the countless spectators” who wanted to follow the proceedings (p. 254).[4] Ruckman “urged” the War Department to select a “prestigious court”.[4]:255 Three brigadier generals were chosen, along with seven full colonels and three lieutenant colonels. Eight members of the court were West Point graduates.

The court contained a geographic balance between northerners, southerners and westerners.[citation needed]

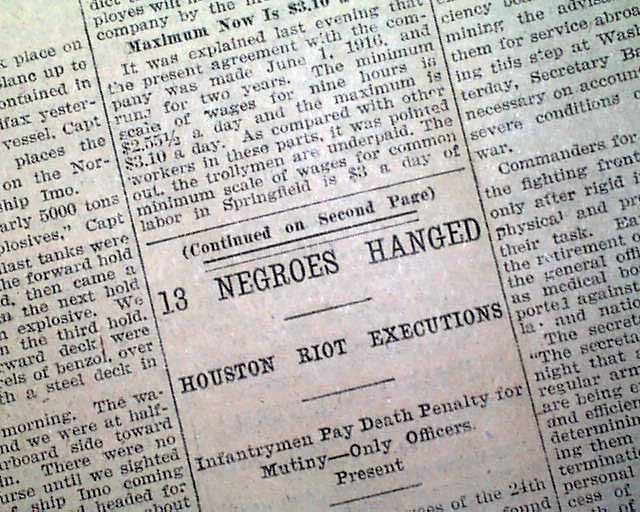

The Departmental Judge Advocate General, Colonel George Dunn, reviewed the record of the first court martial (known as “the Nesbit Case.”) and approved the sentences. He forwarded the documents materials to Gen. Ruckman on December 3. Six days later, thirteen of the prisoners (including Corporal Baltimore) were told that they would be hanged for murder, but they were not informed of the time or place.[4]:3 The court recommended clemency for a Private Hudson, but General Ruckman declined to grant it. Many soldiers were wrongly accused because no witnesses were able to distinguish the soldiers during the riot.

how the hell they allow themselves to get arrested!

They must be honored.

They must be honored.