Two Egyptian texts, one dated to the period of

Amenhotep III (14th century BCE), the other to the age of

Ramesses II (13th century BCE), refer to

t3 š3św yhw,

[6] i.e. "Yahu in the land of the Šosū-nomads", in which

yhw[3]/Yahu

is a toponym.

Hieroglyph Name Pronunciation

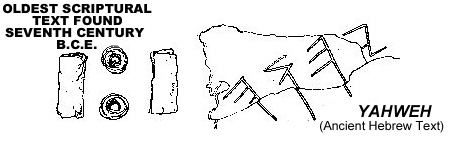

Regarding the name

yhw3, Michael Astour observed that the "hieroglyphic rendering corresponds very precisely to the

Hebrew tetragrammaton

YHWH, or

Yahweh, and antedates the hitherto oldest occurrence of that divine name – on the

Moabite Stone – by over five hundred years."

[7] K. Van Der Toorn concludes: "By the 14th century BC, before the cult of Yahweh had reached Israel, groups of

Edomites and

Midianites worshipped Yahweh as their god."

[8]

Donald B. Redford has argued that the earliest Israelites, semi-nomadic highlanders in central Palestine mentioned on the

Merneptah Stele at the end of the 13th century BCE, are to be identified as a Shasu enclave. Since later Biblical tradition portrays Yahweh "coming forth from

Seʿir",

[9] the Shasu, originally from

Moab and northern Edom/Seʿir, went on to form one major element in the amalgam that would constitute the "Israel" which later established the

Kingdom of Israel.

[10] Per his own analysis of the

el-Amarna letters,

Anson Rainey concluded that the description of the Shasu best fits that of the early Israelites.

[11] If this identification is correct, these Israelites/Shasu would have settled in the uplands in small villages with buildings similar to contemporary Canaanite structures towards the end of the 13th century BCE.

[12]

Objections exist to this proposed link between the

Israelites and the Shasu, given that the group in the Merneptah reliefs identified with the Israelites are not described or depicted as Shasu (see

Merneptah Stele § Karnak reliefs). The Shasu are usually depicted hieroglyphically with a

determinative indicating a land, not a people;

[13] the most frequent designation for the "foes of Shasu" is the

hill-country determinative.

[14] Thus they are differentiated from the

Canaanites, who are defending the fortified cities of Ashkelon,

Gezer, and

Yenoam; and from Israel, which is determined as a people, though not necessarily as a socio-ethnic group.

[15][16] Scholars point out that Egyptian scribes tended to bundle up "rather disparate groups of people within a single artificially unifying rubric."

[17][18]

Frank J. Yurco and Michael G. Hasel would distinguish the Shasu in Merneptah's Karnak reliefs from the people of Israel since they wear different clothing and hairstyles,[

verification needed] and are determined differently by Egyptian scribes.[

verification needed]

[19] Lawrence Stager also objected to identifying Merneptah's Shasu with Israelites, since the Shasu are shown dressed differently from the Israelites, who are dressed and hairstyled like the Canaanites.

[15][20]

The usefulness of the determinatives has been called into question, though, as in Egyptian writings, including the Merneptah Stele, determinatives are used arbitrarily.

[21] Moreover, the hill-country determinative is not always used for Shasu, as is the case in the "Shasu of Yhw" name rings from Soleb and Amarah-West.[

citation needed] Gösta Werner Ahlström countered Stager's objection by arguing that the contrasting depictions are because the Shasu were the nomads, while the Israelites were sedentary, and added: "The Shasu that later settled in the hills became known as Israelites because they settled in the territory of Israel".

[20]