The Remarkable Variety of Caribbean Cornmeal

Caribbean fungi—no relation to mushrooms—is ready for its stateside close-up.

October 20, 2022

In Caribbean restaurants across America, patrons have become accustomed to common dishes such as jerk chicken, beef patties, and oxtail. The heat and vibrance of Caribbean food has made a splash stateside, but some of the more home-style, foundational dishes are still struggling to gain attention in the restaurant space.

Fungi—pronounced “foon-ji,” with no relation to mushrooms—is one of them. A staple Caribbean cornmeal dish flaked with okra and laced with butter can be found throughout the islands, particularly in the West Indies and

Virgin Islands. The thickened, earthy porridge-like dish has roots in slavery itself, and is one of many dishes that demonstrates the importance of cornmeal in Caribbean foodways.

Most native Virgin Islanders fondly remember fungi as a part of their childhoods, and as a key element of fish and fungi, a common meal

.

But the recipe also represents an important piece of Virgin Islands history. Fungi’s roots extend back to the 18th century when, under colonial rule, food was rationed for enslaved Africans on the islands as part of a 1755 law that required slave owners to provide enslaved persons with corn flour or cassava, as well as salt pork.

In his 1992 book, “Slave Society in the Danish West Indies,” the author and professor Neville A.T. Hall writes that this amount would have been two and a half quarts of cassava or cornmeal per week, a small amount considering the hard labor required during harvest season. To fill in the gaps, enslaved Africans grew their own provisions on land hidden from slave owners. Okra, a key ingredient in West African cooking brought to the Caribbean by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, was likely added to the cornmeal around this time, increasing the dish’s nutritional value, adding an earthy flavor and stretching it into a meal that could feed many.

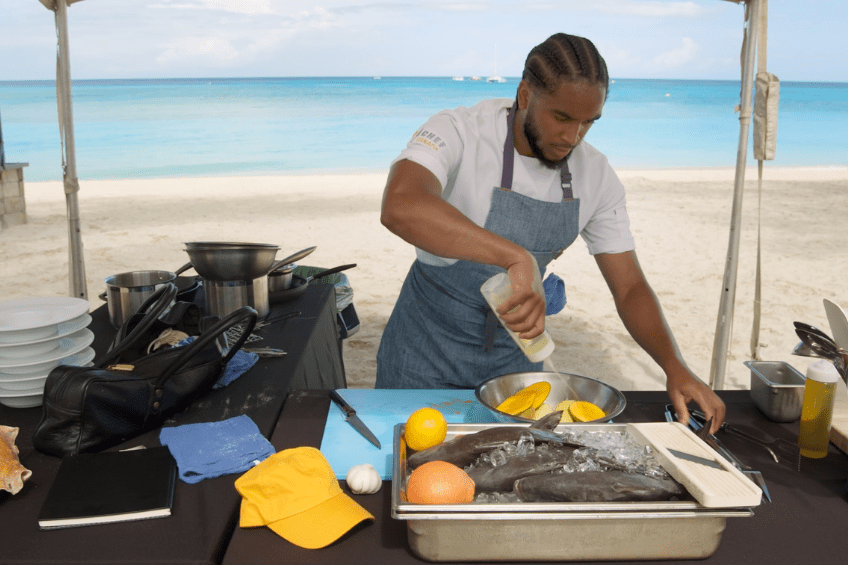

Preserving this part of Virgin Islands history is important for Julius Jackson, the chef and manager at

the cafe and bakery of

My Brother’s Workshop, a nonprofit organization that teaches managerial skills and culinary arts in Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas.

“When they make it, they usually say their grandparents and the adults in their life eat fungi,” Mr. Jackson said of his students.

The decline in the dish’s popularity isn’t unexpected, as it requires more preparation than other staples like fried plantains or rice and beans. The process of whipping, or “turning” it, is a time-consuming task that prevents lumps and aerates the mixture.

But the appeal of fungi is that it uses few ingredients to create a flavorful accompaniment to a stewed or fried protein.

In the cafe and in Mr. Jackson’s cookbook, “My Modern Caribbean Kitchen,” his recipe for fungi is simplified: Cook the okra until tender before whisking in a steady stream of cornmeal. The goal of his lessons at the cafe — and this simplification — is to encourage a new generation of cooks to make fungi at home.

A staple with synonyms

Ramin Ganeshram, a journalist, food writer, trained chef, and executive director of Connecticut’s

Westport Museum for History and Culture, explains, “We call [fungi] cou cou [sometimes written as “coo coo”] in Trinidad, and it's called different things in different parts of the Caribbean.”

She explained that cornmeal-based fungi takes a variety of shapes across the Caribbean community. Her first memory eating the cornmeal is the way it’s still cooked in Trinidad: with okra. It’s molded into a cake-like or molded figure or some sort, then sliced and eaten with any kind of stewed dish.

“Corntastic” cornmeal

Ganeshram went on to say that cornmeal itself makes cameos in various guises throughout the Caribbean, and that the diversity of cooked cornmeal shows the range of Caribbean foodways. Beyond fungi and cou cou, it’s also used for pastelles, which are similar to tamales stuffed with seasoned meats, wrapped in banana leaves, and steamed. (Tamales and pastelles are

different from Puerto Rican pasteles, which have a plantain–green banana mash base.) On the islands, it’s also common to see cornmeal combined with flour to make Caribbean dumplings.

“The Caribbean is often seen as this monolith to Americans,” says Ganeshram. “They assume that Caribbean food is the same, and all Caribbean accents are the same, and yet we see these incredible distinctions from island to island.”

Queens native

Brittney “Stikxz” Williams agrees. The private chef and caterer describes fungi as something that's more prevalent in the Virgin Islands and Barbados. In her Jamaican household growing up, however, her family ate cornmeal in the form of a slightly sweetened porridge. The chef recalls learning as a young girl that the porridge had been considered a form of sustenance for generations.

“It was something that was always eaten for breakfast to sustain [you] hunger, especially for those growing up on farmland [who] were responsible for attending to the land,” she said.

A cuisine beyond jerk chicken

Recognizing the more unassuming dishes within Caribbean cuisine gives people the opportunity to taste essential Caribbean history and culture, says Ganeshram, who has tried for years to shift the narrative about what island cuisine is about.

Chef Williams is likewise eager to bring fungi and similar cornmeal dishes to the Caribbean cuisine story, saying that it’s rarely given full attention and credit in restaurant settings. She's tried to counter the idea that cornmeal can’t be used in creative or refined Caribbean dining (polenta, for example, appears on some of the finest Italian menus in the country), and incorporates cornmeal in her menus.

“I love to introduce cornmeal at my dinners whenever I [have] multiple courses, or anything of that sort, because I want everyone to really understand the gravity [of cornmeal] and how impactful each of these specific ingredients hold true to West Indian culture, and to the Caribbean diaspora,” said Williams