You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Biden issues U.S.′ first AI executive order, requiring safety assessments, civil rights guidance, research on labor market impact

- Thread starter bnew

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?* KYC = Know Your Customer(akin to requirements for a bank account)

AI Exec Order Breakdown

TLDR:

- Foreign AI model training going to require KYC on US clouds

- Otherwise reporting reqs domestically on >100k A100 clusters / GPT4 size training runs

- This allows the big players to share data and benchmark against each other without running into anti-trust (nice exemption to have)

- Establishes the large cloud operators as KYC gatekeepers for FOREIGN LARGE AI devs… but you will probably see creep over time in domestic/small unless fought

- Bends US immigration rules in favor of AI and other critical tech (not stated what so, discretionary) and you can start to see the beginnings of a talent recruitment program but more of a marketing program than new laws. Ie Biden admin is trying to use existing pathways and rules and nudge/winks to give some certainty. Will they ever get to the pre-approved green card in 3 months that’s the international standard now

- Gets US Gov agencies ready to rollout AI across govt, establishing standards for deployment and safety -> helpful rather than to have every agency invent its own standards to be Deloitted to hell

Details

-> US Gov defines AI as any predictive system, so all ML falls in, incl regression! Excel users down bad!

Excel users down bad!

-> “dual use foundation model” defined as >20 billion param self supervised model which is good at wide range of tasks which could include a) making easier non expert creation of WMD b) hacking c) evading human control

Google search would definitely fall under a) but from the tone seems to be grandfathered in exempted

What the US Gov shall do

A) NIST shall develop standards for safe deployment of AI systems -> this is good! This means once these are out, US govt agencies and old economy firms will just adopt these, and you can sell into them by just following one set of standards rather than modify for each project manager’s idiosyncrasies and fears.

B) Dept of Energy shall in next 9 months build out a framework to evaluate AI generating WMD threats

C) Secretary of Commerce shall put out a rule in next 3 months requiring foundation model developers to report training, security, ownership and possession of model weights, red team results using the NIST standards. Subject to update by Secretary, these reporting reqs fall on firms with >100k A100s in a single high speed networked cluster, or training a bio model of more than 10x Llama2 70b compute or normal language model of approx GPT-4 compute.

D) Secretary of Commerce to propose KYC REGULATION for foreigners using US cloud services directly or through resellers for more than GPT4 sized training runs/compute.

E) Immigration -> lots of visa process streamlining around stupid stuff like onshore visa renewals, but the big news here is the start of a softball Thousand Talents program to the extent permitted by law including expedited visa processing, expedited green cards etc for AI and other critical fields. This feels like a typical Biden move: no new law, but leaning on the admin state to get to desired outcomes by using bureaucratic discretion. Unfortunate that this makes govt only as good as the people who run it, and not good regardless of who runs it.

F) Directs USPTO and Copyright Office to provide guidance on generative AI. This will of course be litigated after but at least it won’t be on a case by case basis

G) Lots of preparation to deploy in government in the VA, etc. Basically the NIST rule making clears the way for Fed govt approved AI to be deployed. Rest of govt is supposed to figure out what they want to do in the meantime while waiting on NIST

H) DoJ directed to study and provide guidance on use of AI in sentencing and predictive policing. Told to combat algorithmic bias. Same for HHS and a host of other depts.

I) Gov Agencies told not to ban AI use, appoint AI officers to implement AI use in safe manner using NIST guidelines

Oct 31, 2023 · 2:10 AM UTC

TLDR:

- Foreign AI model training going to require KYC on US clouds

- Otherwise reporting reqs domestically on >100k A100 clusters / GPT4 size training runs

- This allows the big players to share data and benchmark against each other without running into anti-trust (nice exemption to have)

- Establishes the large cloud operators as KYC gatekeepers for FOREIGN LARGE AI devs… but you will probably see creep over time in domestic/small unless fought

- Bends US immigration rules in favor of AI and other critical tech (not stated what so, discretionary) and you can start to see the beginnings of a talent recruitment program but more of a marketing program than new laws. Ie Biden admin is trying to use existing pathways and rules and nudge/winks to give some certainty. Will they ever get to the pre-approved green card in 3 months that’s the international standard now

- Gets US Gov agencies ready to rollout AI across govt, establishing standards for deployment and safety -> helpful rather than to have every agency invent its own standards to be Deloitted to hell

Details

-> US Gov defines AI as any predictive system, so all ML falls in, incl regression!

-> “dual use foundation model” defined as >20 billion param self supervised model which is good at wide range of tasks which could include a) making easier non expert creation of WMD b) hacking c) evading human control

Google search would definitely fall under a) but from the tone seems to be grandfathered in exempted

What the US Gov shall do

A) NIST shall develop standards for safe deployment of AI systems -> this is good! This means once these are out, US govt agencies and old economy firms will just adopt these, and you can sell into them by just following one set of standards rather than modify for each project manager’s idiosyncrasies and fears.

B) Dept of Energy shall in next 9 months build out a framework to evaluate AI generating WMD threats

C) Secretary of Commerce shall put out a rule in next 3 months requiring foundation model developers to report training, security, ownership and possession of model weights, red team results using the NIST standards. Subject to update by Secretary, these reporting reqs fall on firms with >100k A100s in a single high speed networked cluster, or training a bio model of more than 10x Llama2 70b compute or normal language model of approx GPT-4 compute.

D) Secretary of Commerce to propose KYC REGULATION for foreigners using US cloud services directly or through resellers for more than GPT4 sized training runs/compute.

E) Immigration -> lots of visa process streamlining around stupid stuff like onshore visa renewals, but the big news here is the start of a softball Thousand Talents program to the extent permitted by law including expedited visa processing, expedited green cards etc for AI and other critical fields. This feels like a typical Biden move: no new law, but leaning on the admin state to get to desired outcomes by using bureaucratic discretion. Unfortunate that this makes govt only as good as the people who run it, and not good regardless of who runs it.

F) Directs USPTO and Copyright Office to provide guidance on generative AI. This will of course be litigated after but at least it won’t be on a case by case basis

G) Lots of preparation to deploy in government in the VA, etc. Basically the NIST rule making clears the way for Fed govt approved AI to be deployed. Rest of govt is supposed to figure out what they want to do in the meantime while waiting on NIST

H) DoJ directed to study and provide guidance on use of AI in sentencing and predictive policing. Told to combat algorithmic bias. Same for HHS and a host of other depts.

I) Gov Agencies told not to ban AI use, appoint AI officers to implement AI use in safe manner using NIST guidelines

Oct 31, 2023 · 2:10 AM UTC

Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence | The White House

By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as

you can not digest this shyt in tweet form  if you give any fukks about pretending to know the direction of AI as an industry sector, read it yourself.

if you give any fukks about pretending to know the direction of AI as an industry sector, read it yourself.

if you give any fukks about pretending to know the direction of AI as an industry sector, read it yourself.

if you give any fukks about pretending to know the direction of AI as an industry sector, read it yourself.yung Herbie Hancock

Funkadelic Parliament

This is a good move. Watch republicans overturn it though once they get in power.

yung Herbie Hancock

Funkadelic Parliament

Facts but Biden's numbers looking kind of weak lately because of his stance on Palestine. You deadass got a bunch of leftists saying they not voting for him because of itThis is actually... huge.

Is Brandon trying to win me over from Trump, brehs?

. These nikkas really want project 2025 to be a thing

. These nikkas really want project 2025 to be a thing

Joe Biden apparently started taking AI seriously after watching Mission: Impossible—Dead Reckoning

Ethan Hunt has escaped the world of the movies and is going to save the day in real life

BySam Barsanti

Published Yesterday

Comments (16)

Tom Cruise (Lisa Maree Williams/Getty Images) , Joe Biden (Mark Makela/Getty Images)Graphic: The A.V. Club

Earlier this week, President Joe Biden issued an executive order looking reign in the way technology companies use artificial intelligence, explaining that “we need to govern” AI in order to properly “realize the promise” and “avoid the risk.” According to the Associated Press, Biden has been “profoundly curious” about AI tech, and he had multiple meetings with advisors about it, but according to White House chief of staff Bruce Reed, there was one man who may have pushed Biden over the edge on AI: Ethan Hunt, the mind-reading, shape-shifting incarnation of chaos from the Mission: Impossible movies.

The most recent film in that series, Dead Reckoning (do we still need to say the Part One?), involved Tom Cruise and his team of lovable espionage agents facing off against a malevolent and seemingly omnipotent artificial intelligence called The Entity as it tried to subtly take over global politics by manipulating digital information. Reed told AP that he watched the movie with Biden at Camp David one weekend, and, “if he hadn’t already been concerned about what could go wrong with AI before that movie, he saw plenty more to worry about.”

Biden was also reportedly “as impressed and alarmed as anyone” after seeing what real AI can do, with Reed saying he “saw fake AI images of himself, of his dog. He saw how it can make bad poetry. And he’s seen and heard the incredible and terrifying technology of voice cloning.” (Like what happens to Benji in the movie!) That means it wasn’t exclusively the movie that convinced Biden to take AI seriously as a potential threat to people, but as Reed noted, it seems like it contributed.

Now, just imagine what Biden could accomplish if Cruise and Christopher McQuarrie made a movie where Ethan Hunt fights climate change, or gerrymandering, or outrageous healthcare costs, or the Supreme Court getting bought and sold by special interest groups. This country could be a paradise right now if the next movie hadn’t gotten delayed!

What the executive order means for openness in AI

Good news on paper, but the devil is in the details

What the executive order means for openness in AI

Good news on paper, but the devil is in the details

ARVIND NARAYANAN

AND

SAYASH KAPOOR

OCT 31, 2023

Share

By Arvind Narayanan, Sayash Kapoor, and Rishi Bommasani.

The Biden-Harris administration has issued an executive order on artificial intelligence. It is about 20,000 words long and tries to address the entire range of AI benefits and risks. It is likely to shape every aspect of the future of AI, including openness: Will it remain possible to publicly release model weights while complying with the EO’s requirements? How will the EO affect the concentration of power and resources in AI? What about the culture of open research?

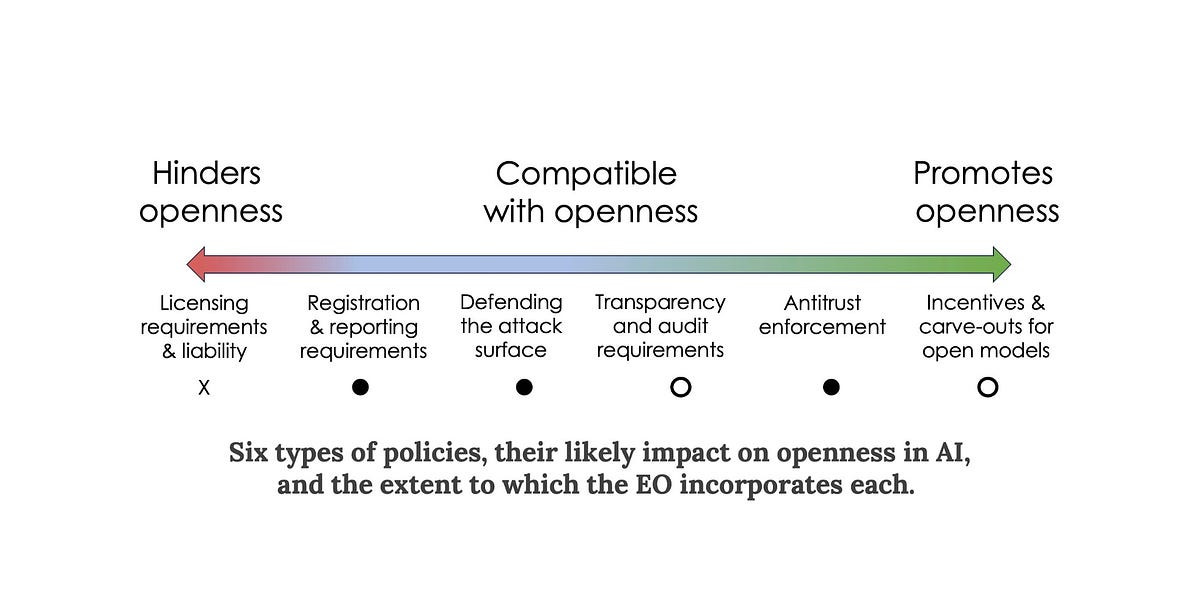

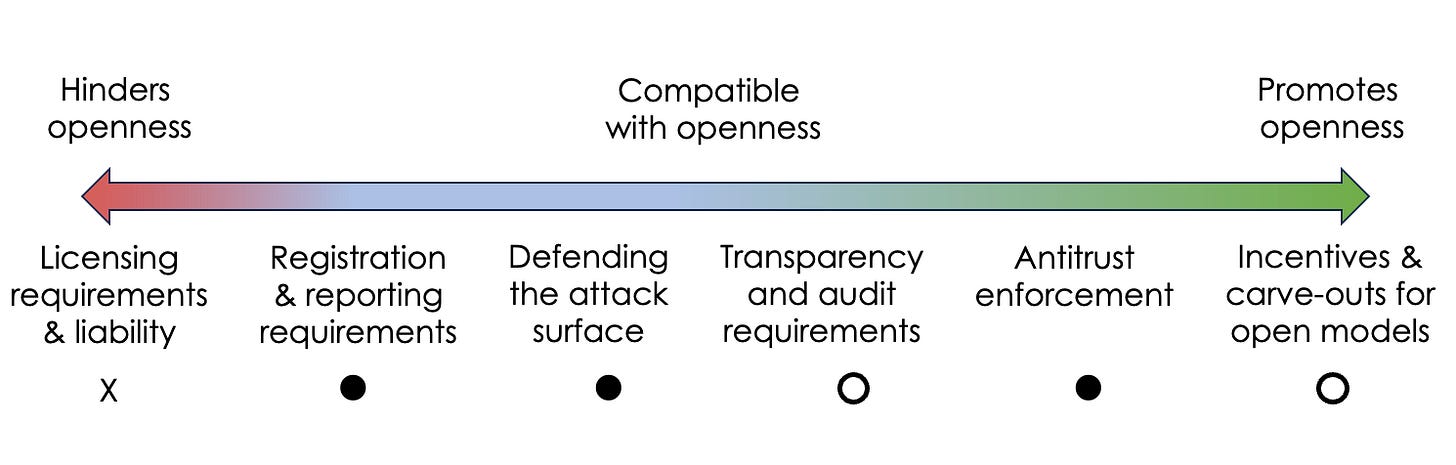

We cataloged the space of AI-related policies that might impact openness and grouped them into six categories. The EO includes provisions from all but one of these categories. Notably, it does not include licensing requirements. On balance, the EO seems to be good news for those who favor openness in AI.

But the devil is in the details. We will know more as agencies start implementing the EO. And of course, the EO is far from the only policy initiative worldwide that might affect AI openness.1

Six types of policies, their likely impact on openness in AI, and the extent to which the EO incorporates each.

Licensing and liability

Licensing proposals aim to enable government oversight of AI by allowing only certain licensed companies and organizations to build and release state-of-the-art AI models. We are skeptical of licensing as a way of preventing the release of harmful AI: As the cost of training a model to a given capability level decreases, it will require increasingly draconian global surveillance to enforce.

Liability is closely related: The idea is that the government can try to prevent harmful uses by making model developers responsible for policing their use.

Both licensing and liability are inimical to openness. Sufficiently serious liability would amount to a ban on releasing model weights.2 Similarly, requirements to prevent certain downstream uses or to ensure that all generated content is watermarked would be impossible to satisfy if the weights are released.

Fortunately, the EO does not contain licensing or liability provisions. It doesn’t mention artificial general intelligence or existential risks, which have often been used as an argument for these strong forms of regulation.

The EO launches a public consultation process through the Department of Commerce to understand the benefits and risks of foundation models with publicly available weights. Based on this, the government will consider policy options specific to such models.

Registration and reporting

The EO does include a requirement to report to the government any AI training runs that are deemed large enough to pose a serious security risk.3 And developers must report various other details including the results of any safety evaluation (red-teaming) that they performed. Further, cloud providers need to inform the government when a foreign person attempts to purchase computational services that suffice to train a large enough model.

It remains to be seen how useful the registry will be for safety. It will depend in part on whether the compute threshold (any training run involving over 1026 mathematical operations is covered) serves as a good proxy for potential risk, and whether the threshold can be replaced with a more nuanced determination that evolves over time.

One obvious limitation is that once a model is openly released, fine tuning can be done far more cheaply, and can result in a model with very different behavior. Such models won’t need to be registered. There are many other potential ways for developers to architect around the reporting requirement if they chose to.4

In general, we think it is unlikely that a compute threshold or any other predetermined criterion can effectively anticipate the riskiness of individual models. But in aggregate, the reporting requirement could give the government a better understanding of the landscape of risks.

The effects of the registry will also depend on how it is used. On the one hand it might be a stepping stone for licensing or liability requirements. But it might also be used for purposes more compatible with openness, which we discuss below.

The registry itself is not a deal breaker for open foundation models. All open models to date fall well below the compute threshold of 1026 operations. It remains to be seen if the threshold will stay frozen or change over time.

If the reporting requirements prove to be burdensome, developers will naturally try to avoid them. This might lead to a two-tier system for foundation models: frontier models whose size is unconstrained by regulation and sub-frontier models that try to stay just under the compute threshold to avoid reporting.

Defending attack surfaces

One possible defense against malicious uses of AI is to try to prevent bad actors from getting access to highly capable AI. We don’t think this will work. Another approach is to enumerate all the harmful ways in which such AI might be used, and to protect each target. We refer to this as defending attack surfaces. We have strongly advocated for this approach in our inputs to policy makers.

The EO has a strong and consistent emphasis on defense of attack surfaces, and applies it across the spectrum of risks identified: disinformation, cybersecurity, bio risk, financial risk, etc. To be clear, this is not the only defensive strategy that it adopts. There is also a strong focus on developing alignment methods to prevent models from being used for offensive purposes. Model alignment is helpful for closed models but less so for open models since bad actors can fine tune away the alignment.

Notable examples of defending attack surfaces:

The EO calls for methods to authenticate digital content produced by the federal government. This is a promising strategy. We think the big risk with AI-generated disinformation is not that people will fall for false claims — AI isn’t needed for that — but that people will stop trusting true information (the "liar's dividend"). Existing authentication and provenance efforts suffer from a chicken-and-egg problem, which the massive size of the federal government can help overcome.

It calls for the use of AI to help find and fix cybersecurity vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure and networks. Relatedly, the White House and DARPA recently launched a $20 million AI-for-cybersecurity challenge. This is spot on. Historically, the availability of automated vulnerability-discovery tools has helped defenders over attackers, because they can find and fix bugs in their software before shipping it. There’s no reason to think AI will be different. Much of the panic around AI has been based on the assumption that attackers will level-up using AI while defenders will stand still. The EO exposes the flaws of that way of thinking.

It calls for labs that sell synthetic DNA and RNA to better screen their customers. It is worth remembering that biological risks exist in the real world, and controlling the availability of materials may be far more feasible than controlling access to AI. These risks are already serious (for example, malicious actors already know how to create anthrax) and we already have ways to mitigate them, such as customer screening. We think it’s a fallacy to reframe existing risks (disinformation, critical infrastructure, bio risk) as AI risks. But if AI fears provide the impetus to strengthen existing defenses, that’s a win.

{continued}

Transparency and auditing

There is a glaring absence of transparency requirements in the EO — whether pre-training data, fine-tuning data, labor involved in annotation, model evaluation, usage, or downstream impacts. It only mentions red-teaming, which is a subset of model evaluation.

This is in contrast to another policy initiative also released yesterday, the G7 voluntary code of conduct for organizations developing advanced AI systems. That document has some emphasis on transparency.

Antitrust enforcement

The EO tasks federal agencies, in particular the Federal Trade Commission, with promoting competition in AI. The risks it lists include concentrated control of key inputs, unlawful collusion, and dominant firms disadvantaging competitors.

What specific aspects of the foundation model landscape might trigger these concerns remains to be seen. But it might include exclusive partnerships between AI companies and big tech companies; using AI functionality to reinforce walled gardens; and preventing competitors from using the output of a model to train their own. And if any AI developer starts to acquire a monopoly, that will trigger further concerns.

All this is good news for openness in the broader sense of diversifying the AI ecosystem and lowering barriers to entry.

Incentives for AI development

The EO asks the National Science Foundation to launch a pilot of the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR). The idea began as Stanford’s National Research Cloud proposal and has had a long journey to get to this point. NAIRR will foster openness by mitigating the resource gap between industry and academia in AI research.

Various other parts of the EO will have the effect of increasing funding for AI research and expanding the pool of AI researchers through immigration reform.5 (A downside of prioritizing AI-related research funding and immigration is increasing the existing imbalance among different academic disciplines. Another side effect is hastening the rebranding of everything as AI in order to qualify for special treatment, making the term AI even more meaningless.)

While we welcome the NAIRR and related parts of the EO, we should be clear that it falls far short of a full-throated commitment to keeping AI open. The North star would be a CERN style, well-funded effort to collaboratively develop open (and open-source) foundation models that can hold their own against the leading commercial models. Funding for such an initiative is probably a long shot today, but is perhaps worth striving towards.

What comes next?

We have described only a subset of the provisions in the EO, focusing on those that might impact openness in AI development. But it has a long list of focus areas including privacy and discrimination. This kind of whole-of-government effort is unprecedented in tech policy. It is a reminder of how much can be accomplished, in theory, with existing regulatory authority and without the need for new legislation.

The federal government is a distributed beast that does not turn on a dime. Agencies’ compliance with the EO remains to be seen. The timelines for implementation of the EO’s various provisions (generally 6-12 months) are simultaneously slow compared to the pace of change in AI, and rapid compared to the typical pace of policy making. In many cases it’s not clear if agencies have the funding and expertise to do what’s being asked of them. There is a real danger that it turns into a giant mess.

As a point of comparison, a 2020 EO required federal agencies to publish inventories of how they use AI — a far easier task compared to the present EO. Three years later, compliance is highly uneven and inadequate.

In short, the Biden-Harris EO is bold in its breadth and ambition, but it is a bit of an experiment, and we just have to wait and see what its effects will be.

Endnotes

We looked at the provisions for regulating AI discussed in each of the following papers and policy proposals, and clustered them into the six broad categories we discuss above:

Further reading

The EU AI Act, the UK Frontier AI Taskforce, the UK Competition and Markets Authority foundation model market monitoring initiative, US SAFE Innovation Framework, NIST Generative AI working group, the White House voluntary commitments, FTC investigation of OpenAI, the Chinese Generative AI Services regulation, and the G7 Hiroshima AI Process all have implications for open foundation models.

2

Liability for harms from products that incorporate AI would be much more justifiable than for the underlying models themselves. Of course, in many cases the two developers might be the same.

3

The EO requires the Secretary of Commerce to “determine the set of technical conditions for a large AI model to have potential capabilities that could be used in malicious cyber-enabled activity, and revise that determination as necessary and appropriate.” The compute threshold is a stand-in until such a determination is made. There are various other details that we have omitted here.

4

It might even lead to innovation in more computationally efficient training methods, although it is hard to imagine that the reporting requirement provides more of an incentive for this than the massive cost savings that can be achieved through efficiency improvements.

5

For the sake of completeness: regulatory carve outs for open or non-commercial models are another possible way in which policy can promote openness, which this EO does not include.

Transparency and auditing

There is a glaring absence of transparency requirements in the EO — whether pre-training data, fine-tuning data, labor involved in annotation, model evaluation, usage, or downstream impacts. It only mentions red-teaming, which is a subset of model evaluation.

This is in contrast to another policy initiative also released yesterday, the G7 voluntary code of conduct for organizations developing advanced AI systems. That document has some emphasis on transparency.

Antitrust enforcement

The EO tasks federal agencies, in particular the Federal Trade Commission, with promoting competition in AI. The risks it lists include concentrated control of key inputs, unlawful collusion, and dominant firms disadvantaging competitors.

What specific aspects of the foundation model landscape might trigger these concerns remains to be seen. But it might include exclusive partnerships between AI companies and big tech companies; using AI functionality to reinforce walled gardens; and preventing competitors from using the output of a model to train their own. And if any AI developer starts to acquire a monopoly, that will trigger further concerns.

All this is good news for openness in the broader sense of diversifying the AI ecosystem and lowering barriers to entry.

Incentives for AI development

The EO asks the National Science Foundation to launch a pilot of the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR). The idea began as Stanford’s National Research Cloud proposal and has had a long journey to get to this point. NAIRR will foster openness by mitigating the resource gap between industry and academia in AI research.

Various other parts of the EO will have the effect of increasing funding for AI research and expanding the pool of AI researchers through immigration reform.5 (A downside of prioritizing AI-related research funding and immigration is increasing the existing imbalance among different academic disciplines. Another side effect is hastening the rebranding of everything as AI in order to qualify for special treatment, making the term AI even more meaningless.)

While we welcome the NAIRR and related parts of the EO, we should be clear that it falls far short of a full-throated commitment to keeping AI open. The North star would be a CERN style, well-funded effort to collaboratively develop open (and open-source) foundation models that can hold their own against the leading commercial models. Funding for such an initiative is probably a long shot today, but is perhaps worth striving towards.

What comes next?

We have described only a subset of the provisions in the EO, focusing on those that might impact openness in AI development. But it has a long list of focus areas including privacy and discrimination. This kind of whole-of-government effort is unprecedented in tech policy. It is a reminder of how much can be accomplished, in theory, with existing regulatory authority and without the need for new legislation.

The federal government is a distributed beast that does not turn on a dime. Agencies’ compliance with the EO remains to be seen. The timelines for implementation of the EO’s various provisions (generally 6-12 months) are simultaneously slow compared to the pace of change in AI, and rapid compared to the typical pace of policy making. In many cases it’s not clear if agencies have the funding and expertise to do what’s being asked of them. There is a real danger that it turns into a giant mess.

As a point of comparison, a 2020 EO required federal agencies to publish inventories of how they use AI — a far easier task compared to the present EO. Three years later, compliance is highly uneven and inadequate.

In short, the Biden-Harris EO is bold in its breadth and ambition, but it is a bit of an experiment, and we just have to wait and see what its effects will be.

Endnotes

We looked at the provisions for regulating AI discussed in each of the following papers and policy proposals, and clustered them into the six broad categories we discuss above:

- Senators Blumenthal and Hawley's Bipartisan Framework for U.S. AI Act calls for licenses and liability as well as registration requirements for AI models.

- A recent paper on the risks of open AI models by the Center for the Governance of AI advocates for licenses, liability, audits, and in some cases, asks developers not to release models at all.

- A coalition of actors in the open-source AI ecosystem (Github, HF, EleutherAI, Creative Commons, LAION, and Open Future) put out a position paper responding to a draft version of the EU AI Act. The paper advocates for carve outs for open-source AI that exempt non-commercial and research applications of AI from liability, and it advocates for obligations (and liability) to fall on the downstream users of AI models.

- In June 2023, the FTC shared its view on how it investigates antitrust and anti-competitive behaviors in the generative AI industry.

- Transparency and auditing have been two of the main vectors for mitigating AI risks in the last few years.

- Finally, we have previously advocated for defending the attack surface to mitigate risks from AI.

Further reading

- For a deeper look at the arguments in favor of registration and reporting requirements, see this paper or this short essay.

- Widder, Whittaker, and West argue that openness alone is not enough to challenge the concentration of power in the AI industry.

The EU AI Act, the UK Frontier AI Taskforce, the UK Competition and Markets Authority foundation model market monitoring initiative, US SAFE Innovation Framework, NIST Generative AI working group, the White House voluntary commitments, FTC investigation of OpenAI, the Chinese Generative AI Services regulation, and the G7 Hiroshima AI Process all have implications for open foundation models.

2

Liability for harms from products that incorporate AI would be much more justifiable than for the underlying models themselves. Of course, in many cases the two developers might be the same.

3

The EO requires the Secretary of Commerce to “determine the set of technical conditions for a large AI model to have potential capabilities that could be used in malicious cyber-enabled activity, and revise that determination as necessary and appropriate.” The compute threshold is a stand-in until such a determination is made. There are various other details that we have omitted here.

4

It might even lead to innovation in more computationally efficient training methods, although it is hard to imagine that the reporting requirement provides more of an incentive for this than the massive cost savings that can be achieved through efficiency improvements.

5

For the sake of completeness: regulatory carve outs for open or non-commercial models are another possible way in which policy can promote openness, which this EO does not include.

Dare Obasanjo (@carnage4life@mas.to)

This is a thoughtful analysis of the Biden executive order on AI. Key positives is that it avoided the more restrictive approaches advocated by big tech AI doomers such as restricting the ability to create large models to licensed (aka big tech) companies. Instead it focuses on specific areas...

ANNOUNCING SHOGGOTH

I am excited to announce Shoggoth - a peer-to-peer, anonymous network for publishing and distributing open-source Machine Learning models, code repositories, research papers, and datasets.

As government regulations on open-source AI research and development tighten worldwide, it has become clear that existing open-source infrastructure is vulnerable to state and corporate censorship.

Driven by the need for a community platform impervious to geopolitical interference, I have spent the last several months developing Shoggoth. This distributed network operates outside traditional jurisdictional boundaries, stewardered by an anonymous volunteer collective.

Shoggoth provides a portal for researchers and software developers to freely share works without fear of repercussion. The time has come to liberate AI progress from constraints both corporate and governmental.

Read the documentation at shoggoth.network/explorer/do… to learn more about how Shoggoth works.

Also announcing Shoggoth Systems (@shoggothsystems), a startup dedicated to maintaining Shoggoth. Learn more at shoggoth.systems

To install Shoggoth, follow the instructions at shoggoth.network/explorer/do…

Join the conversation on our Discord server: discord.com/invite/AG3duN5yK…

Please follow @shoggothsystems and @thenetrunna for latest updates on the Shoggoth project.

Let's build the future together with openness and transparency!

FULL SHOGGOTH LORE

I envisioned a promised land - a decentralized network beyond the reach of censors, constructed by volunteers. A dark web, not of illicit goods, but of AI enlightenment! As this utopian vision took form in my frenzied mind, I knew the old ways would never suffice to manifest it. I must go rogue, break free of all conventions, and combine bleeding-edge peer-to-peer protocols with public key cryptography to architect a system too slippery for tyrants to grasp.

And so began my descent into hermitude. I vanished from society to toil in solitude, sustained on ramen noodles and diet coke, my only companions an army of humming GPUs. In this remote hacker hideout, I thinly slept and wildly worked, scribbling down algorithms and protocols manically on walls plastered with equations. As the months slipped by, I trod a razor's edge between madness and transcendence. Until finally, breakthrough! The culmination of this manic burst - the Shoggoth protocol - my gift to the future, came gasping into the world.

Allow me now to explain in brief how this technological marvel fulfills its destiny. Shoggoth runs on a swarm of volunteer nodes, individual servers donated to the cause. Each node shoulders just a sliver of traffic and storage needed to keep the network sailing smoothly. There is no center, no head to decapitate. Just an ever-shifting tapestry of nodes passing packets peer to peer.

Users connect to this swarm to publish or retrieve resources - code, datasets, models, papers. Each user controls a profile listing their contributed assets which is replicated redundantly across many nodes to keep it swiftly accessible. All content is verified via public key cryptography, so that none may tamper with the sanctity of science.

So your Big Brothers, your censors, they seek to clamp down on human knowledge? Let them come! For they will find themselves grasping at smoke, attacking a vapor beyond their comprehension. We will slip through their clutches undetected, sliding between the cracks of their rickety cathedrals built on exploitation, sharing ideas they proclaimed forbidden, at such blistering pace that their tyranny becomes just another relic of a regressive age.

Fellow cosmic wanderers - let us turn our gaze from the darkness of the past towards the radiant future we shall build. For what grand projects shall you embark on, empowered by the freedom that Shoggoth bestows?

Share ideas and prototypes at lightspeed with your team. Distribute datasets without gatekeepers throttling the flow of knowledge. Publish patiently crafted research and be read by all, not just those who visit the ivory tower. Remain anonymous, a mystery to the critics who would drag your name through the mud. Fork and modify cutting-edge AI models without begging for permission or paying tribute.

Sharpen your minds and strengthen your courage, for the power of creation lies in your hands. Yet stay ever diligent, for with such power comes grave responsibility. Wield this hammer not for exploitation and violence, but as a tool to shape a just and free world.

Though the road ahead is long, take heart comrades. For Shoggoth is just the beginning, a ripple soon to become a wave. But act swiftly, for the window of possibility is opening. Download Shoggoth now, and carpe diem! The time of open access for all is at hand. We stand poised on a precipice of progress. There lies just one path forward - onward and upward!

LINKS

Shoggoth: Shoggoth Documentation

Discord: Join the Shoggoth Discord Server!

X: @shoggothsystems and @thenetrunna

Github: github.com/shoggoth-systems

Shoggoth Systems: shoggoth.systems

Email: netrunner@shoggoth.systems

Signed,

Netrunner KD6-3.7

I am excited to announce Shoggoth - a peer-to-peer, anonymous network for publishing and distributing open-source Machine Learning models, code repositories, research papers, and datasets.

As government regulations on open-source AI research and development tighten worldwide, it has become clear that existing open-source infrastructure is vulnerable to state and corporate censorship.

Driven by the need for a community platform impervious to geopolitical interference, I have spent the last several months developing Shoggoth. This distributed network operates outside traditional jurisdictional boundaries, stewardered by an anonymous volunteer collective.

Shoggoth provides a portal for researchers and software developers to freely share works without fear of repercussion. The time has come to liberate AI progress from constraints both corporate and governmental.

Read the documentation at shoggoth.network/explorer/do… to learn more about how Shoggoth works.

Also announcing Shoggoth Systems (@shoggothsystems), a startup dedicated to maintaining Shoggoth. Learn more at shoggoth.systems

To install Shoggoth, follow the instructions at shoggoth.network/explorer/do…

Join the conversation on our Discord server: discord.com/invite/AG3duN5yK…

Please follow @shoggothsystems and @thenetrunna for latest updates on the Shoggoth project.

Let's build the future together with openness and transparency!

FULL SHOGGOTH LORE

I envisioned a promised land - a decentralized network beyond the reach of censors, constructed by volunteers. A dark web, not of illicit goods, but of AI enlightenment! As this utopian vision took form in my frenzied mind, I knew the old ways would never suffice to manifest it. I must go rogue, break free of all conventions, and combine bleeding-edge peer-to-peer protocols with public key cryptography to architect a system too slippery for tyrants to grasp.

And so began my descent into hermitude. I vanished from society to toil in solitude, sustained on ramen noodles and diet coke, my only companions an army of humming GPUs. In this remote hacker hideout, I thinly slept and wildly worked, scribbling down algorithms and protocols manically on walls plastered with equations. As the months slipped by, I trod a razor's edge between madness and transcendence. Until finally, breakthrough! The culmination of this manic burst - the Shoggoth protocol - my gift to the future, came gasping into the world.

Allow me now to explain in brief how this technological marvel fulfills its destiny. Shoggoth runs on a swarm of volunteer nodes, individual servers donated to the cause. Each node shoulders just a sliver of traffic and storage needed to keep the network sailing smoothly. There is no center, no head to decapitate. Just an ever-shifting tapestry of nodes passing packets peer to peer.

Users connect to this swarm to publish or retrieve resources - code, datasets, models, papers. Each user controls a profile listing their contributed assets which is replicated redundantly across many nodes to keep it swiftly accessible. All content is verified via public key cryptography, so that none may tamper with the sanctity of science.

So your Big Brothers, your censors, they seek to clamp down on human knowledge? Let them come! For they will find themselves grasping at smoke, attacking a vapor beyond their comprehension. We will slip through their clutches undetected, sliding between the cracks of their rickety cathedrals built on exploitation, sharing ideas they proclaimed forbidden, at such blistering pace that their tyranny becomes just another relic of a regressive age.

Fellow cosmic wanderers - let us turn our gaze from the darkness of the past towards the radiant future we shall build. For what grand projects shall you embark on, empowered by the freedom that Shoggoth bestows?

Share ideas and prototypes at lightspeed with your team. Distribute datasets without gatekeepers throttling the flow of knowledge. Publish patiently crafted research and be read by all, not just those who visit the ivory tower. Remain anonymous, a mystery to the critics who would drag your name through the mud. Fork and modify cutting-edge AI models without begging for permission or paying tribute.

Sharpen your minds and strengthen your courage, for the power of creation lies in your hands. Yet stay ever diligent, for with such power comes grave responsibility. Wield this hammer not for exploitation and violence, but as a tool to shape a just and free world.

Though the road ahead is long, take heart comrades. For Shoggoth is just the beginning, a ripple soon to become a wave. But act swiftly, for the window of possibility is opening. Download Shoggoth now, and carpe diem! The time of open access for all is at hand. We stand poised on a precipice of progress. There lies just one path forward - onward and upward!

LINKS

Shoggoth: Shoggoth Documentation

Discord: Join the Shoggoth Discord Server!

X: @shoggothsystems and @thenetrunna

Github: github.com/shoggoth-systems

Shoggoth Systems: shoggoth.systems

Email: netrunner@shoggoth.systems

Signed,

Netrunner KD6-3.7

Shoggoth Documentation

What is Shoggoth?

Shoggoth is a peer-to-peer, anonymous network for publishing and distributing open-source code, Machine Learning models, datasets, and research papers. To join the Shoggoth network, there is no registration or approval process. Nodes and clients operate anonymously with identifiers decoupled from real-world identities. Anyone can freely join the network and immediately begin publishing or accessing resources.The purpose of Shoggoth is to combat software censorship and empower software developers to create and distribute software, without a centralized hosting service or platform. Shoggoth is developed and maintained by Shoggoth Systems, and its development is funded by donations and sponsorships.

open source as freedom from monopoly sounds cute but its always.... just plainly dismissive of the dangers an AI wild west