That's what you perceive, but it doesn't apply to all cops. I didn't think I was living a movie.

I was never in a "hyper aggressive" and combative mode. I treated everyone the same: white, black, Asian, Hispanic, male or female.

I never lured civilians into confrontation.

And, I worked in predominately black neighborhoods too.

You and every cop needs to realize that implicit bias plays a big role in the disproportionate killing of black suspects. If you want to make a difference, please read about these studies and demand Fair and Impartial Policing training NATIONWIDE. Denying that there is a problem does not make it go away.

The Police Officer's Dilemma

The Paradigm

Since 2000, we have been working to develop and refine a first-person-shooter videogame, which presents a series of images of young men, some armed, some unarmed, set against realistic backgrounds like parks or city streets. The player's goal is to shoot any and all armed targets, but not to shoot unarmed targets. Half of the targets are Black, and half are White. We have used this game to investigate whether decisions to "shoot" a potentially hostile target can be influenced by that target's race.

Basic Findings

Our research has provided robust evidence of racial bias in decisions to shoot (Correll, Park, Judd & Wittenbrink, 2002; Correll, Park, Judd, Wittenbrink, Sadler & Keesee, in press; Correll, Urland & Ito, 2006). Participants shoot an armed target more quickly and more often when that target is Black, rather than White. However, participants decide not to shoot an unarmed target more quickly and more often when the target is White, rather than Black. In essence, participants seem to process stereotype-consistent targets (armed Blacks and unarmed Whites) more easily than counterstereotypic targets (unarmed Blacks and armed Whites).

Moreover, by recording fluctuations in the brain's electrical activity (ERPs), we have observed that participants differentiate between Black and White targets about 230 milliseconds after the target appears on screen. This type of differentiation has also been observed when participants see a threatening (vs. a non-threatening) image. Strikingly, the more participants differentiate by target race (processing Black targets as if they were threats), the more bias they show on our task (Correll, Urland & Ito, 2006; see Ito & Urland, 2003, 2004, for more on race and ERPs).

Additional Resources

To read more on this line of research, please see the Publications page.

Try an online version of the First-Person Shooter Task

To download the First-Person Shooter Task and image files

For a version programmed in E-Prime 2.0, click here.

For a version programmed in Psyscope, click here

FPST

‘Deadly force’ lab finds racial disparities in shootings

September 2, 2014

By Eric Sorensen, WSU science writer

SPOKANE, Wash. – Participants in an innovative Washington State University study of deadly force were more likely to feel threatened in scenarios involving black people. But when it came time to shoot, participants were biased in favor of black suspects, taking longer to pull the trigger against them than against armed white or Hispanic suspects.

The findings, published in the recent Journal of Experimental Criminology, grow out of dozens of simulations aimed at explaining the disproportionate number of ethnic and racial minorities shot by police. The studies use the most advanced technology available, as participants with laser-equipped guns react to potentially threatening scenarios displayed in full-size, high-definition video.

The findings surprised Lois James, lead author and assistant research professor at WSU Spokane’s Sleep and Performance Research Center. Other, less realistic studies have found people are more willing to think a black person has a gun instead of a tool and will more readily push a “shoot” button against a potentially armed black person.

The findings also run counter to the public perception, heightened with the recent shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., that police are more willing to shoot black suspects. Statistics show that police shoot ethnic and racial minorities disproportionately to their population.

But the last comprehensive look at the racial makeup of justifiable and non-justifiable shootings was a 2001 study (http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ph98.pdf) using more than two decades of U.S. Bureau of Justice data, said James. And while statistics show black suspects are shot at more frequently than white suspects, the 2001 study found black suspects were also as likely to shoot at police as be shot at.

“At the moment, there are no comprehensive statistics on whether the police do inappropriately shoot at black males more than they do at white males,” said James. “Although isolated incidents of black males being shot by the police are devastating and well documented, at the aggregate level we need to understand whether the police are shooting black unarmed males more than they are white unarmed males. And at the moment, nobody knows that.”

Shootings in the field are particularly difficult to study because they can have a multitude of complex, confounding and hard-to-control variables. But WSU Spokane’s Simulated Hazardous Operational Tasks Laboratory can control variables like suspect clothing, hand positions, threatening stance and race, while giving observers precise data on when participants are fired upon and how many milliseconds they take to fire back.

James’ study is a follow-up to one in which she found active police officers, military personnel and the general public took longer to shoot black suspects than white or Hispanic suspects. Participants were also more likely to shoot unarmed white suspects than black or Hispanic ones and more likely to fail to fire at armed black suspects.

“In other words,” wrote James and her co-authors, “there was significant bias favoring blacks where decisions to shoot were concerned.”

When confronted by an armed white person, participants took an average of 1.37 seconds to fire back. Confronted by an armed black person, they took 1.61 seconds to fire and were less likely to fire in error. The 240-millisecond difference may seem small, but it’s enough to be fatal in a shooting.

The recent study analyzed data from electroencephalograph sensors that measured participants’ alpha brain waves, which are suppressed in situations that appear threatening.

The participants, 85 percent of whom were white, “demonstrated significantly greater threat responses against black suspects than white or Hispanic suspects,” wrote James and her co-authors, University of Missouri-St. Louis criminologist David Klinger and WSU Spokane’s Bryan Vila. This, they said, suggests the participants “held subconscious biases associating blacks and threats,” which is consistent with previous psychological research on racial stereotypes.

However, the current study only measured the alpha waves of participants drawn from the general public, not law enforcement or the military. Consequently, wrote the authors, “results from this sample are not generalizable to sworn officers.”

“However,” they added, “there is some evidence from the field to support the proposition that an officer’s threat bias could cause him or her to tend to take more time to make decisions to shoot people whom they subconsciously perceived as more threatening because of race or ethnicity. This behavioral ‘counter-bias’ might be rooted in people’s concerns about the social and legal consequences of shooting a member of a historically oppressed racial or ethnic group.”

James said she has data on subconscious associations between race and threat from law enforcement subjects, and she awaits funding to analyze whether these biases predict decisions to shoot in the simulator. Like study participants from the general public, she said, “they were still more hesitant to shoot black suspects than white suspects. They took longer and they made fewer errors.”

Funding for the study came from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the National Institute of Justice and the Office of Naval Research.

Contacts:

Lois James, WSU Spokane assistant research professor, 509-358-7944, lois_james@wsu.edu

Eric Sorensen, WSU science writer, 509-335-4846, c: 206-799-9186, eric.sorensen@wsu.edu

‘Deadly force’ lab finds racial disparities in shootings | WSU News | Washington State University

The Psychology of Bias

Last edited:

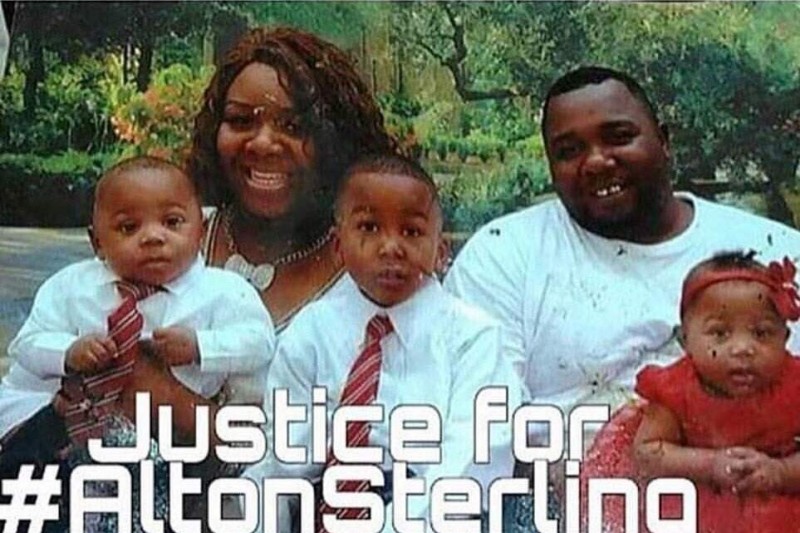

this one is WORSE than the Baton Rouge shooting

this one is WORSE than the Baton Rouge shooting