OLD ARTICLE from 2007

Her specialty: celebrating the black Brahmins

Longtime Brookline resident Adelaide Cromwell, 87, recounts the history of her illustrious family in her latest book, "Unveiled Voices, Unvarnished Memories," which stretches over three centuries. November 4, 2007

Brookline is home to many esteemed academics, published authors with busy book-promotion tours, African-Americans, and octogenarians.

Adelaide Cromwell may be the only Brookline resident who is all of the above. And as if to show that it's all easier than one thinks, the 87-year-old has just published another book on the accomplishments of her forebears.

The book, "Unveiled Voices, Unvarnished Memories," is the history of the Cromwell family from 1692 to 1972.

Her grandfather was a lawyer and newspaper publisher, a descendant of slaves who purchased their own freedom.

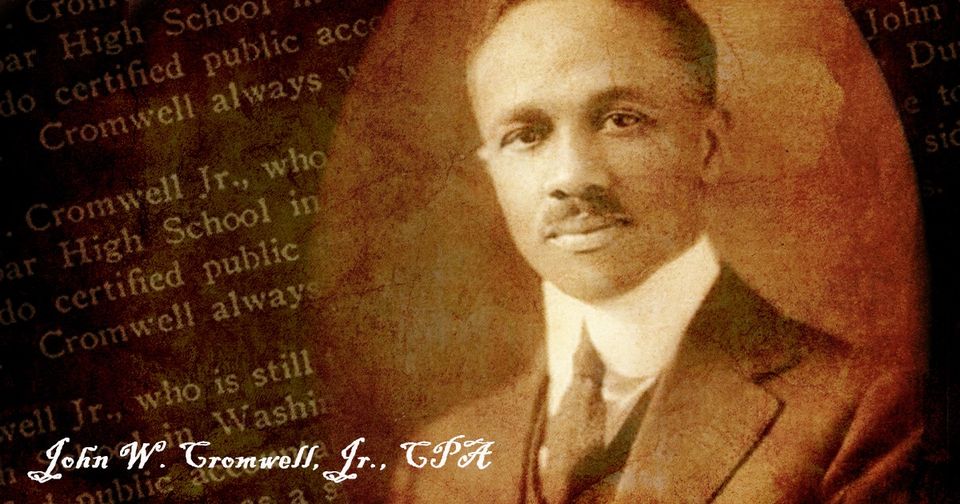

John Cromwell Jr.

"My father was one of many well-educated people" in the black community of Washington, D.C., she said, noting he was a Phi Beta Kappa member at Dartmouth College (class of 1906). He was Washington's first black practicing certified public accountant*, she said, and, because he couldn't get promoted in a segregated society, eventually became his own boss.

*(Acknowledged as the first Black C.P.A. in America) The Black CPA Association marks their centennial on Cromwell's achievement

Senator Edward Brooke

Other Cromwell relatives include cousin Edward Brooke, who was the first black to be elected to the US Senate by popular vote when Massachusetts sent him to Washington in 1966. Like Adelaide, he was born in 1919 and has a new book out: "Bridging the Divide: My Life."

Otelia Cromwell

And then there's her aunt, Otelia Cromwell, the first black graduate (class of 1900) of Smith College in Northampton. Otelia completed a doctorate in history at Yale.

"She said in a letter to her father that she wasn't going to do her dissertation on the Negro," Cromwell said. "She said, 'Any work I might do in that line would be independent, because naturally I know more about it than most of the people here.' "

Cromwell graduated from the best black high school in Washington, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and went on to complete degrees at Smith - where she is president of her alumnae class - and the University of Pennsylvania.

For her doctoral dissertation at Radcliffe in 1952, she wrote on the black elite of Boston, which she published in 1994 as "The Other Brahmins." On that subject, Cromwell has found many underreported facets to document, such as the black community on Martha's Vineyard, where she maintains a second home, and Boston Latin's African-American graduates.

From the Revolutionary War onward, Boston boasted a small number of educated and accomplished black residents. Because of social and legal restrictions, many of these community leaders didn't attain wealth or social prominence outside the black community, said Cromwell. However, they opened summer homes in Oak Bluffs on the Vineyard, and established the first schools for blacks, and their organizations were covered by William Lloyd Garrison's newspaper, The Liberator.

These families produced the state's first black teachers, doctors, and lawyers. After forming and fighting in one of the all-black regiments in the Civil War, many became Boston leaders, served in government posts, and established exclusive clubs.

Today, surrounded with art and antiques from her work and travels, the diminutive Cromwell is energetic and blunt as she reviewed a career that started when she became the first black professor at Hunter College in 1946, and continued through her cofounding of the African studies program at Boston University in 1953, and her founding of BU's Afro-American studies program in 1969.

Eventually, she became the African studies' administrator. The department was unique at the time, she said, because its focus was on independent, modern Africa, rather than just anthropology or as fertile ground for missionary activities.

"We had panache that other programs didn't have," she said. Africans visiting the United States would come to BU, and part of Cromwell's job would be to show them around.

While studying at Penn, she met Kwame Nkrumah, who went on to lead Ghana after the West African country gained independence from Great Britain. The meeting deepened her early interest in modern Africa.

Other subjects she has covered include Africa's meaning for black Americans, and a biography of a distinguished African feminist, Adelaide Smith Casely Hayford, who opened the first school for girls in Sierra Leone. "She's one of the women," said Cromwell, "who was on the cutting edge of change in Africa."

Cromwell has traveled Africa: to the then-Belgian Congo, to Ghana, and in 1983 to Liberia. Even there, her interest was in the African elites. "I was interested in the people who were becoming leaders," she said. "The Mercedes Africans."

Her broad-ranging activities also included serving on a commission of civilians - she was the only woman and only black - formed after the Charlestown prison riots of 1954. Along with criminologists and mental health professionals, Cromwell visited all of the state's prisons in an attempt to better conditions.

"It was fascinating, because you could see the changes before your eyes," she said of improvements in the prisoners' living conditions in the wake of the disturbances.

After divorcing her husband, she moved to Brookline about 25 years ago, she said, adding that she chose the town for its convenience to the T and its welcoming atmosphere.

"I didn't want a civil rights case," she said.

She also particularly liked the brick town house she was shown. "I liked this house right away," she said. "I grew up in a three-story brick town house just like it." She has one son, Anthony Cromwell Hill, a freelance journalist who graduated Harvard and lives in Cambridge.

Currently, Cromwell is a member of the Massachusetts Historical Commission, and her projects include the placement of historic markers on the former homes of prominent African-American men and women in Boston - mostly Beacon Hill - with the Heritage Guild, which she serves as president.

"I'm always finding something that needs doing," she said.

.

.