Bolivia’s African King Speaks For Coca Growers

“People don’t understand that it is not a drug.”

By Bill Weinberg

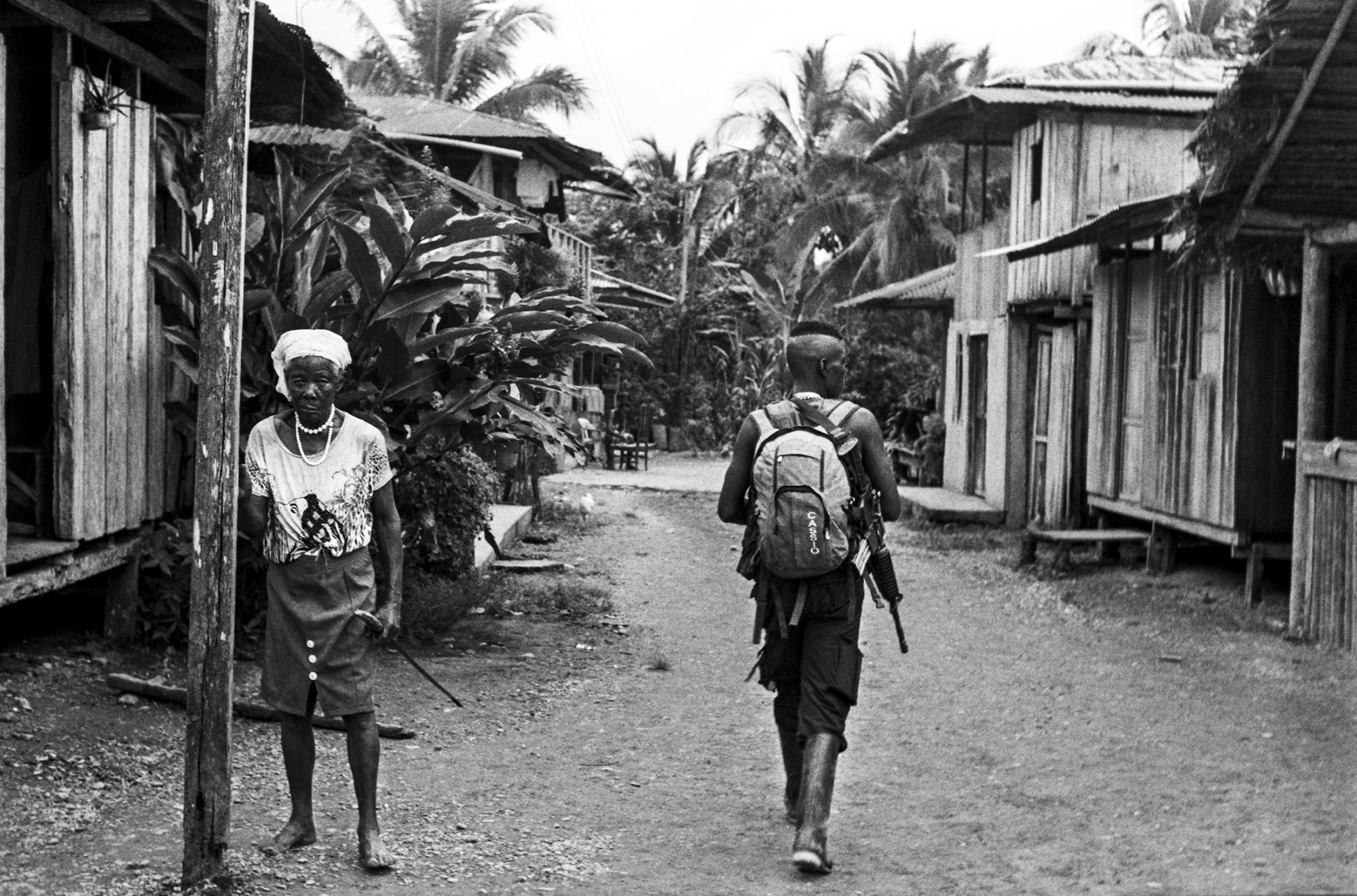

Among the coca-growing peasants of Bolivia’s Yungas region (the country’s prime legal cultivation zone) is a substantial Afro-Bolivian population—descendants of slaves who were brought in by the Spanish colonialists to work in the silver mines and haciendas centuries ago. Some have inter-married with the indigenous Aymara people of the Yungas, forming a distinctive Afro-Aymara culture.

The Guardian recently noted the 10th anniversary of the coronation of the “King of the Afro-Bolivians,” Julio I—said to be South America’s last reigning monarch, although he lives as a cocalero and grocery-shop keeper in the little village of Mururata. His dominion—recognized by the Bolivian government—extends to a few dozen rural villages, as well as some city dwellers who together make up the 25,000-strong Afro-Bolivian community.

A profile last year in Guatemala’s Prensa Libre noted wryly that Julio Pinedo, 75, “is probably the poorest king in the world,” and that he works eight hours a day in his coca fields. Although already regarded as the king of the Afro-Bolivians in the Yungas, he was formally crowned on December 3, 2007, in a ceremony recognized by the national authorities in La Paz.

The African Kingdom In The Coca Zone

Julio was declared king by virtue of his descent from Prince Uchicho, who established an autonomous zone of freed slaves in the Yungas when Bolivia won its freedom from Spain.

This legendary figure arrived in Bolivia from Senegal in 1820, after crossing the ocean on one of the last slave ships to leave West Africa. He was sold to a hacienda in the Yungas.

Bolivia was then in the midst of its war of independence, which was won five years later. Slavery was abolished in the country’s 1826 constitution. Because he had been the son of a Kikongo tribal king in Africa, Uchicho became the leader of liberated slaves of the Yungas and was declared their king in 1832. The community grew as freed slaves from the silver mines of Potosí began joining their kin in the more fertile lands of the Yungas. They learned to grow coca from their Aymara neighbors.

Julio received family lore about his royal descent from his father, a community leader named Bonifacio who in 1932 (the centenary of Uchicho’s coronation) established the Royal House of Afrobolivia and was named the first monarch of the revived kingdom. Bonifacio died in 1954, and Julio succeded him upon reaching adulthood.

“Without doubt the king’s role is important,” Zenaida Pérez of the Afro-Bolivian Language and Culture Institute told The Guardian. “He represents much of what our Mother Africa has left us.”

Bolivia’s 2008 constitution recognizes the autonomy of African descendants, and recent years have seen the first Afro-Bolivian legislators and civil servants. Over the past decade, an Afro-Bolivian cultural renaissance has flowered, with a re-awakening of the people’s identity. In 2016, Julio, his wife Angela and their grandson and crown prince Rolando visited Senegal, Congo and other African countries to try to re-establish contact with their long-lost relatives.

Coca Leaf & Cultural Survival: Bolivia’s African King Speaks For Coca Growers

The coca leaf that is indigenous to the Yungas is now an integral part of Afro-Bolivian culture.

Their people have been growing it for generations, and they are today very much a part of the effort to expand the legal internal market for the leaf in Bolivia, where it is widely used for chewing and máte (herbal tea)—and to decouple the plant from the narco stigma.

As Julio wrote in an autobiographical essay for The Guardian: “We grew citrus, coffee and most of all coca—the ‘sacred’ leaf, as this is what gives us life. Without coca there would be nothing in the Yungas. Coca is our means of support; it allows our children to go to school; it feeds us, dresses us and gives us life. People don’t understand that it is not a drug. We don’t even know how to make cocaine; we have never touched it, seen it or tasted it.”

Bolivia’s African King Speaks For Coca Growers

“People don’t understand that it is not a drug.”

By Bill Weinberg

Among the coca-growing peasants of Bolivia’s Yungas region (the country’s prime legal cultivation zone) is a substantial Afro-Bolivian population—descendants of slaves who were brought in by the Spanish colonialists to work in the silver mines and haciendas centuries ago. Some have inter-married with the indigenous Aymara people of the Yungas, forming a distinctive Afro-Aymara culture.

The Guardian recently noted the 10th anniversary of the coronation of the “King of the Afro-Bolivians,” Julio I—said to be South America’s last reigning monarch, although he lives as a cocalero and grocery-shop keeper in the little village of Mururata. His dominion—recognized by the Bolivian government—extends to a few dozen rural villages, as well as some city dwellers who together make up the 25,000-strong Afro-Bolivian community.

A profile last year in Guatemala’s Prensa Libre noted wryly that Julio Pinedo, 75, “is probably the poorest king in the world,” and that he works eight hours a day in his coca fields. Although already regarded as the king of the Afro-Bolivians in the Yungas, he was formally crowned on December 3, 2007, in a ceremony recognized by the national authorities in La Paz.

The African Kingdom In The Coca Zone

Julio was declared king by virtue of his descent from Prince Uchicho, who established an autonomous zone of freed slaves in the Yungas when Bolivia won its freedom from Spain.

This legendary figure arrived in Bolivia from Senegal in 1820, after crossing the ocean on one of the last slave ships to leave West Africa. He was sold to a hacienda in the Yungas.

Bolivia was then in the midst of its war of independence, which was won five years later. Slavery was abolished in the country’s 1826 constitution. Because he had been the son of a Kikongo tribal king in Africa, Uchicho became the leader of liberated slaves of the Yungas and was declared their king in 1832. The community grew as freed slaves from the silver mines of Potosí began joining their kin in the more fertile lands of the Yungas. They learned to grow coca from their Aymara neighbors.

Julio received family lore about his royal descent from his father, a community leader named Bonifacio who in 1932 (the centenary of Uchicho’s coronation) established the Royal House of Afrobolivia and was named the first monarch of the revived kingdom. Bonifacio died in 1954, and Julio succeded him upon reaching adulthood.

“Without doubt the king’s role is important,” Zenaida Pérez of the Afro-Bolivian Language and Culture Institute told The Guardian. “He represents much of what our Mother Africa has left us.”

Bolivia’s 2008 constitution recognizes the autonomy of African descendants, and recent years have seen the first Afro-Bolivian legislators and civil servants. Over the past decade, an Afro-Bolivian cultural renaissance has flowered, with a re-awakening of the people’s identity. In 2016, Julio, his wife Angela and their grandson and crown prince Rolando visited Senegal, Congo and other African countries to try to re-establish contact with their long-lost relatives.

Coca Leaf & Cultural Survival: Bolivia’s African King Speaks For Coca Growers

The coca leaf that is indigenous to the Yungas is now an integral part of Afro-Bolivian culture.

Their people have been growing it for generations, and they are today very much a part of the effort to expand the legal internal market for the leaf in Bolivia, where it is widely used for chewing and máte (herbal tea)—and to decouple the plant from the narco stigma.

As Julio wrote in an autobiographical essay for The Guardian: “We grew citrus, coffee and most of all coca—the ‘sacred’ leaf, as this is what gives us life. Without coca there would be nothing in the Yungas. Coca is our means of support; it allows our children to go to school; it feeds us, dresses us and gives us life. People don’t understand that it is not a drug. We don’t even know how to make cocaine; we have never touched it, seen it or tasted it.”

Bolivia’s African King Speaks For Coca Growers

has the (second) highest Dutch West Indian population in the US

has the (second) highest Dutch West Indian population in the US

I'm all for them to blow these pipes up until they get whatever they want.

I'm all for them to blow these pipes up until they get whatever they want.

getting there slowly

getting there slowly