Love, Afro-Brazilian Style: Afrodengo Is Making It Easier to Find Black Love in Brazil

Courtesy of Thaisa Moreira Xavier and Jackson Xavier

Thaisa Moreira Xavier met her husband in a Facebook group.

Although she was conscious of her Afro-Brazilian heritage, she had few black friends growing up. The city she lived in and schools she attended were mostly white. But when she moved to Campinas, a city of 1 million approximately two hours outside of Sao Paulo, she decided to be proactive.

“I wanted to increase my connection to Afro-Brazilian people,” she says.

Thaisa joined Afrodengo, an Afro-Brazilian dating community on Facebook. When she finally got up the nerve to post her photo and introduced herself—a requirement of the community—she noticed that one guy who “liked” her photo lived in her city. His name was Jackson Xavier.

She reached out to him on Facebook and they immediately started talking. Two days later, they went out on their first date. She instantly liked his intelligence, responsibility and the way he cared for her. He liked her stubbornness, humor and intelligence as well. Five months later, the couple were married. As Jackson explains:

Before the group, I didn’t even think to look for relationships with black women, and I had never had a black girlfriend. But once I entered the group, I started to focus more on having a relationship with a black person like me because we have similar experiences. The black movement is very strong on the internet, so I entered the group wanting to see more beautiful black people and to have references in my life to black things.

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

Courtesy of Thaisa Moreira Xavier and Jackson Xavier

Afrodengo was created one year ago by Afro-Brazilian journalist and single mother Lorena Ifé, 29, to promote love and marriage among Afro-Brazilians. “Dengo” is a word with African roots that Brazilians—especially Afro-Brazilians—call people to show love and care. Despite the country’s African origins, hundreds of years of slavery and European colonialism have made affection and stable relationships between black women and black men in Brazil unique and unusual.

Now Afro-Brazilians are flocking to the Afrodengo Facebook group to build relationships that they never before considered having. But Ifé not only wants to spark love among Afro-Brazilians; she also wants to help them build relationships with one another so that they can combat racism in Brazil. She explains:

Having relationships between black people is a way to combat racism. Only a black person will know how racism affects you and its consequences in our lives. In a society where we learn to hate ourselves, if we unite with people like us, then we can combat racism with something as simple as having a conscious family.

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

The Afrodengo logo (courtesy of Afrodengo)

To jump-start the group, Ifé invited Afro-Brazilian men and women to post photos and descriptions of themselves. Within a week, it exploded—with both members and photos. At one point, Ifé had more than 10,000 people waiting to be approved to the group. Ifé created an environment where every type of black person, regardless of sexuality, sex, religion or political viewpoint, is welcome.

Today the group is still going strong; having produced at least two marriages and countless couples and friendships. There are more than 100,000 members in the main group and its affiliates (which focus on LGBT members, Christians and body positivity). Ifé plans to turn the Facebook group into an app.

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

Courtesy of Afrodengo

While Afro-Brazilians enjoy the group, some white Brazilians consider Ifé and the group racist because it is exclusively for black people. For African Americans, a dating site for black people seems obvious. But for Brazilians, communities restricted by race are always frowned upon. White Brazilians also want to be a part of the group.

“To this day, I have to deny entrance to white people who want to join the group,” Ifé said.

The creation of Afrodengo stems from Ifé’s personal experiences pursuing amor afrocentrado—”black love”— in Salvador, Brazil. While in a relationship with her son’s father, she felt that their relationship lacked the affection she sees given to white women in Brazil. Soon after they broke up, she tried her hand at online dating and even created a profile on Tinder. But although she lives in a city that is more than 80 percent black, she couldn’t find any black men on the platform.

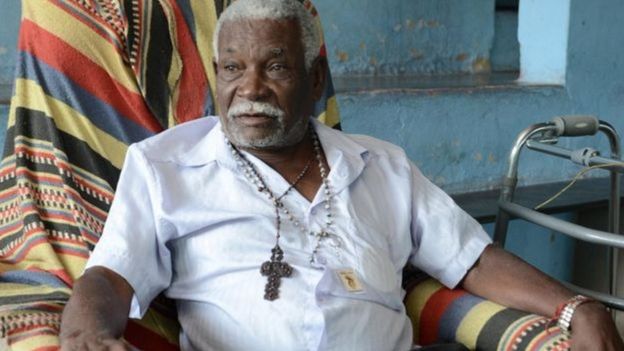

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

Lorena Ifé and her son (Kiratiana Freelon)

Ifé says she wasn’t raised with affection—which is common among poor Afro-Brazilians simply trying to survive. Personally, she longs for a black man who will cherish her intelligence and give her affection when she wants—even when she doesn’t need it. She still longs for an “Afrodengo.”

Creating this Afrodengo [was] a way to help me survive and help others going through a similar situation. It helped me to move on from my relationship and survive my depression.

Ifé’s struggle is one that many black women in Brazil share. Many of their lives are marked by loneliness (solidão da Mulher Negra) because they aren’t chosen—the chosen women being white women. In Brazil, black and mixed-race women have been traditionally oversexualized or looked upon as domestic servants, while white women are viewed as the perfect women to give affection to and to have a healthy marriage with. It is a given that the more money and education an Afro-Brazilian has, the more likely he will marry a white woman.

Translating from a YouTube video by anthropologist Ana Cláudia Pacheco, a professor at the State University of Bahia:

Because of historical reasons related to racism, many black women in Brazil suffer from solitude. ... Our choices in who we give affection to and who we choose as a partner are still regulated by and structured by racism and sexism.

But Afrodengo isn’t just for creating romantic relationships; Afro-Brazilian men and women are using the group to strengthen their black identity and create friendships with Afro-Brazilians across Brazil. Says early adopter Gabriel Rangel, 25, from Rio de Janeiro:

I still haven’t found a relationship through Afrodengo, but now I have friends all over the country, and the group has really opened my mind to the Black Movement in Brazil.

Member Lais Mello entered the group one week after it launched. Adopted by a white family, she’d lacked a strong connection to Afro-Brazilian culture. She created the first city-specific WhatsApp group for Afrodengo, which helped her organize meetups in Salvador and make friends with Afro-Brazilians close to her town in Bahia. Now Mello is a moderator of the group, and credits Afrodengo with increasing her self-esteem and pulling her out of depression:

Before Afrodengo, I wouldn’t leave the house because of my depression and anxiety. My self-esteem was so low. But now I love going to Afrodengo meetups.

Ifé has grand plans for the Afrodengo brand. The first thing she wants to do is get off of Facebook and create an app for the group. She’s currently looking for funding and support, and plans to apply to the Vale de Dendê accelerator, which is targeting Afro-Brazilian startups based in Salvador.

I want to turn Afrodengo into a company that promotes affection between black people, whether it be through books, events, T-shirts, dating apps, everything.

Courtesy of Thaisa Moreira Xavier and Jackson Xavier

Thaisa Moreira Xavier met her husband in a Facebook group.

Although she was conscious of her Afro-Brazilian heritage, she had few black friends growing up. The city she lived in and schools she attended were mostly white. But when she moved to Campinas, a city of 1 million approximately two hours outside of Sao Paulo, she decided to be proactive.

“I wanted to increase my connection to Afro-Brazilian people,” she says.

Thaisa joined Afrodengo, an Afro-Brazilian dating community on Facebook. When she finally got up the nerve to post her photo and introduced herself—a requirement of the community—she noticed that one guy who “liked” her photo lived in her city. His name was Jackson Xavier.

She reached out to him on Facebook and they immediately started talking. Two days later, they went out on their first date. She instantly liked his intelligence, responsibility and the way he cared for her. He liked her stubbornness, humor and intelligence as well. Five months later, the couple were married. As Jackson explains:

Before the group, I didn’t even think to look for relationships with black women, and I had never had a black girlfriend. But once I entered the group, I started to focus more on having a relationship with a black person like me because we have similar experiences. The black movement is very strong on the internet, so I entered the group wanting to see more beautiful black people and to have references in my life to black things.

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

Courtesy of Thaisa Moreira Xavier and Jackson Xavier

Afrodengo was created one year ago by Afro-Brazilian journalist and single mother Lorena Ifé, 29, to promote love and marriage among Afro-Brazilians. “Dengo” is a word with African roots that Brazilians—especially Afro-Brazilians—call people to show love and care. Despite the country’s African origins, hundreds of years of slavery and European colonialism have made affection and stable relationships between black women and black men in Brazil unique and unusual.

Now Afro-Brazilians are flocking to the Afrodengo Facebook group to build relationships that they never before considered having. But Ifé not only wants to spark love among Afro-Brazilians; she also wants to help them build relationships with one another so that they can combat racism in Brazil. She explains:

Having relationships between black people is a way to combat racism. Only a black person will know how racism affects you and its consequences in our lives. In a society where we learn to hate ourselves, if we unite with people like us, then we can combat racism with something as simple as having a conscious family.

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

The Afrodengo logo (courtesy of Afrodengo)

To jump-start the group, Ifé invited Afro-Brazilian men and women to post photos and descriptions of themselves. Within a week, it exploded—with both members and photos. At one point, Ifé had more than 10,000 people waiting to be approved to the group. Ifé created an environment where every type of black person, regardless of sexuality, sex, religion or political viewpoint, is welcome.

Today the group is still going strong; having produced at least two marriages and countless couples and friendships. There are more than 100,000 members in the main group and its affiliates (which focus on LGBT members, Christians and body positivity). Ifé plans to turn the Facebook group into an app.

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

Courtesy of Afrodengo

While Afro-Brazilians enjoy the group, some white Brazilians consider Ifé and the group racist because it is exclusively for black people. For African Americans, a dating site for black people seems obvious. But for Brazilians, communities restricted by race are always frowned upon. White Brazilians also want to be a part of the group.

“To this day, I have to deny entrance to white people who want to join the group,” Ifé said.

The creation of Afrodengo stems from Ifé’s personal experiences pursuing amor afrocentrado—”black love”— in Salvador, Brazil. While in a relationship with her son’s father, she felt that their relationship lacked the affection she sees given to white women in Brazil. Soon after they broke up, she tried her hand at online dating and even created a profile on Tinder. But although she lives in a city that is more than 80 percent black, she couldn’t find any black men on the platform.

View attachment upload_2018-2-4_11-42-53.gif

Lorena Ifé and her son (Kiratiana Freelon)

Ifé says she wasn’t raised with affection—which is common among poor Afro-Brazilians simply trying to survive. Personally, she longs for a black man who will cherish her intelligence and give her affection when she wants—even when she doesn’t need it. She still longs for an “Afrodengo.”

Creating this Afrodengo [was] a way to help me survive and help others going through a similar situation. It helped me to move on from my relationship and survive my depression.

Ifé’s struggle is one that many black women in Brazil share. Many of their lives are marked by loneliness (solidão da Mulher Negra) because they aren’t chosen—the chosen women being white women. In Brazil, black and mixed-race women have been traditionally oversexualized or looked upon as domestic servants, while white women are viewed as the perfect women to give affection to and to have a healthy marriage with. It is a given that the more money and education an Afro-Brazilian has, the more likely he will marry a white woman.

Translating from a YouTube video by anthropologist Ana Cláudia Pacheco, a professor at the State University of Bahia:

Because of historical reasons related to racism, many black women in Brazil suffer from solitude. ... Our choices in who we give affection to and who we choose as a partner are still regulated by and structured by racism and sexism.

But Afrodengo isn’t just for creating romantic relationships; Afro-Brazilian men and women are using the group to strengthen their black identity and create friendships with Afro-Brazilians across Brazil. Says early adopter Gabriel Rangel, 25, from Rio de Janeiro:

I still haven’t found a relationship through Afrodengo, but now I have friends all over the country, and the group has really opened my mind to the Black Movement in Brazil.

Member Lais Mello entered the group one week after it launched. Adopted by a white family, she’d lacked a strong connection to Afro-Brazilian culture. She created the first city-specific WhatsApp group for Afrodengo, which helped her organize meetups in Salvador and make friends with Afro-Brazilians close to her town in Bahia. Now Mello is a moderator of the group, and credits Afrodengo with increasing her self-esteem and pulling her out of depression:

Before Afrodengo, I wouldn’t leave the house because of my depression and anxiety. My self-esteem was so low. But now I love going to Afrodengo meetups.

Ifé has grand plans for the Afrodengo brand. The first thing she wants to do is get off of Facebook and create an app for the group. She’s currently looking for funding and support, and plans to apply to the Vale de Dendê accelerator, which is targeting Afro-Brazilian startups based in Salvador.

I want to turn Afrodengo into a company that promotes affection between black people, whether it be through books, events, T-shirts, dating apps, everything.

artists but PEOPLE... Here in NY I mostly see Central American ppl like Guatemalans bumping that shyt. Most PRs and Dominicans I know moved on to trap.

artists but PEOPLE... Here in NY I mostly see Central American ppl like Guatemalans bumping that shyt. Most PRs and Dominicans I know moved on to trap.

to me there one in the same and I been listening to stuff since it was considered "underground" , I actually consider Spanish trap a evolution of reggaeton

to me there one in the same and I been listening to stuff since it was considered "underground" , I actually consider Spanish trap a evolution of reggaeton

/s.glbimg.com/jo/g1/f/original/2017/01/19/papuda5.jpg)