You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential Afro-Latino/ Caribbean Current Events

- Thread starter Poitier

- Start date

More options

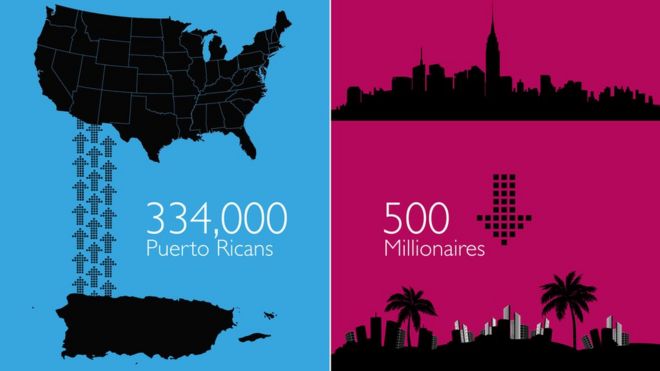

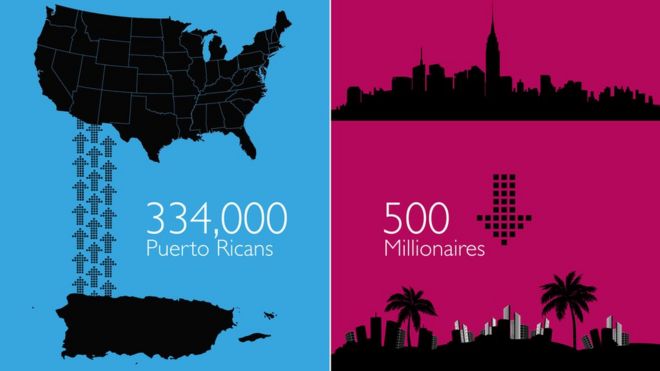

Who Replied?Puerto Rico's population swap: The middle class for millionaires

By Franz StrasserBBC News, Washington

Puerto Rico's struggling economy has led to an exodus of young people moving to the US mainland - while wealthy Americans are starting to call San Juan home. As a result, the economy and identity of both places are changing in surprising ways.

While the US economy is steadily improving, Puerto Rico's unemployment rate has remained at over 13%, twice the US national average, for the last decade. The island is facing a fiscal crisis with $72bn (£47.5bn) in debt.

So the government is looking elsewhere for relief. It has started to lure America's super wealthy from the US East Coast. Two acts passed in 2012 guarantee no capital gains taxes and a mere 4% tax rate on their business to those who make Puerto Rico their primary residence.

More than 500 eligible individuals have answered the call.

"There has been some concern that we're not contributing enough on the island and not everybody is happy about that," says Robb Rill, who moved his business down in 2013.

He says the island is benefitting.

"There's probably been almost a billion dollars invested on the island since these acts have passed, and that's a billion dollars that would not have been invested on the island had there not been the proper incentives. So the everyman on the street doesn't necessarily see the direct benefit, but I can tell you that there is an immeasurable benefit not just on the real estate but through direct investment which is making a difference."

What do they get?

Media player help

Out of media player. Press enter to return or tab to continue.

Media captionA tour of the Ritz Carlton Reserve in Puerto Rico

'Perfect storm'

This influx of mainland monied comes as tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans leave every year. They head in search of more opportunity on the US mainland, where they have the right to work as US citizens.

"What's going on in Puerto Rico right now it's the perfect storm," says Valerie Rodriguez, a young lawyer in San Juan and member of the New Progressive Party.

"You have a population in Puerto Rico where the productive sector is shrinking and the young professionals are leaving. Then you have an elderly population that's increasing in size, and obviously that population is going to depend more and more on government."

Clockwise: the Puerto Rico capitol, Orlando Rivera and his wife in Ponce, and a worker at the San Juan market

Funding those government services is a contentious issue.

"I am the worker, I am the one who is paying the taxes," says Orlando Rivera, a store manager in the city of Ponce. "I have to sustain my family, pay a 400-dollar electrical bill and my daughters' tuition fees. And in the meantime [the millionaires] aren't bringing any solutions to the problem."

Little opportunity

Jump media player

Media player help

Out of media player. Press enter to return or tab to continue.

Media captionPuerto Rico's students sound off

For those who aren't wealthy, staying in Puerto Rico is not always an option.

"Young people here that go to university and prepare themselves, they really want to stay on the island and it's not something they can do." says Ms Rodriguez.

The changing demographics are altering Puerto Rico's relationship with the mainland.

"Students that have decided to leave the island for job opportunities are important for Puerto Rico because they create other opportunities," says Uroyoan Walker, the President of the University of Puerto Rico. "It's very important that the university and the people of Puerto Rico stay connected with that diaspora so that we can become a stronger and bigger country."

The big migration

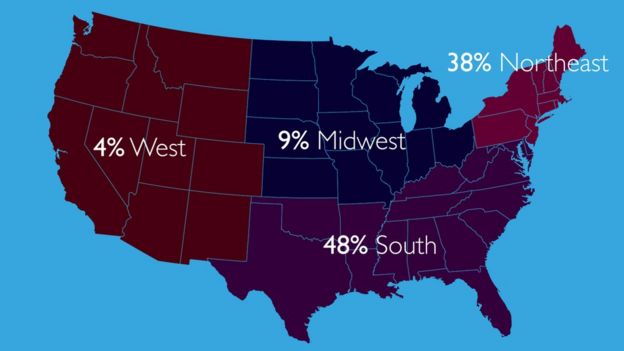

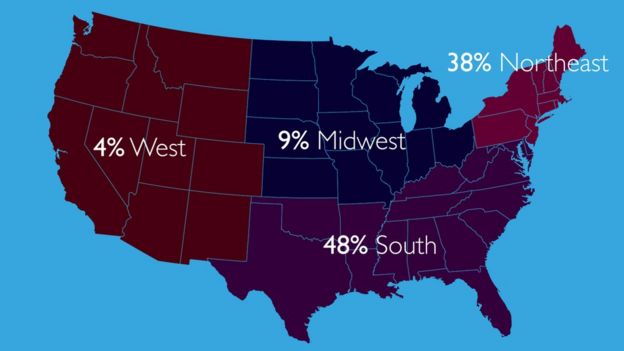

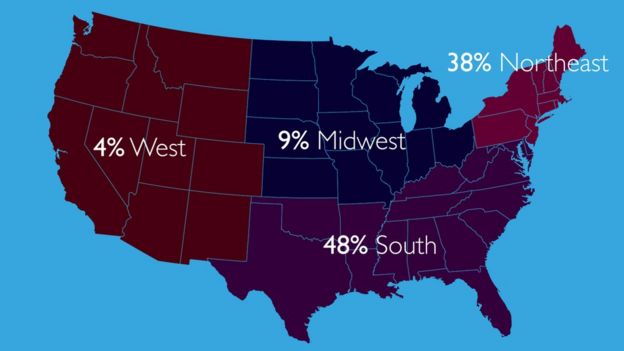

Puerto Ricans moving to the US between 2005-2012 (Source: Pew Research Center)

As citizens of a US territory, Puerto Ricans have the same right to work as any American born in the 50 states. More than 300,000 of them have left the island and headed for the US mainland in the last decade. Traditionally they have moved to New York, but more recently a third of them have moved to Florida. In Central Florida alone, 100 new families arrive every single week.

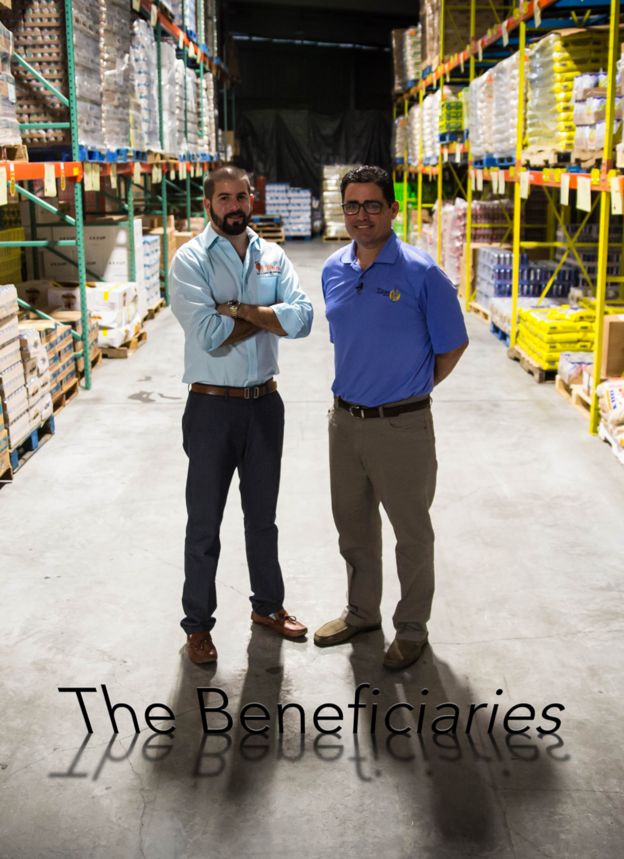

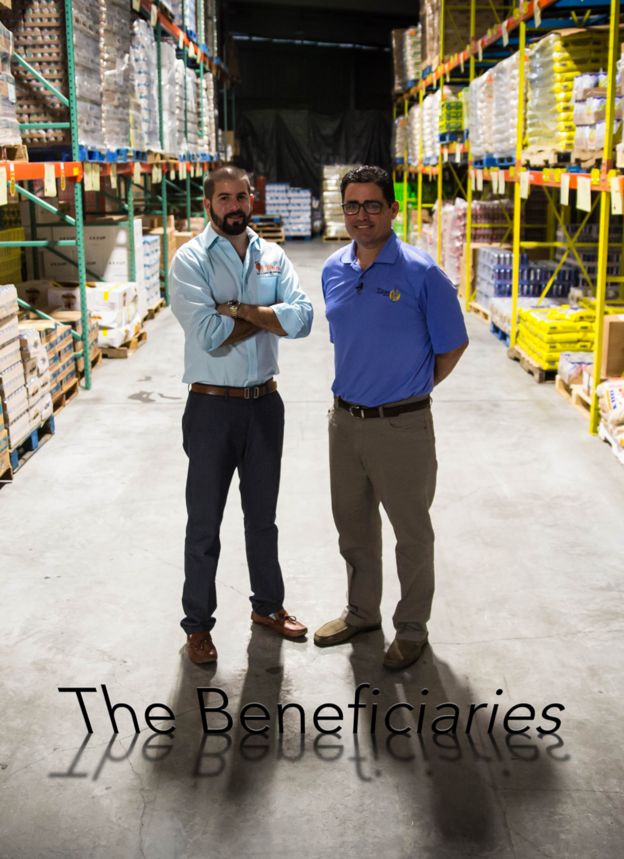

Doubling sales

This increased migration has presented an opportunity for entrepreneurs.

Titan Products of Puerto Rico opened a distribution centre in Central Florida last spring. Over 40,000 square feet of Puerto Rican products are being moved here and shipped across the Southern US.

"People used to travel there and bring back in their luggage, the cookies, the beans, or the rice," says Rafael Julia, the sales director for Titan. Alternatively, they would get products sent through the post or brought back by friends or family, she adds.

"We receive probably one to two containers a week, they come from Puerto Rico, we consolidate all the cargo down there. We have over 176 clients from small bodegas, family-owned, to big supermarkets."

They say their business is booming.

"We can double our sales next year. We are currently talking to big players like Publix and Wal-Mart to have our products there."

Popular products

Florida, Florida, Florida

And where there's people and money the politicians won't be too far behind. Puerto Ricans residing on the mainland have the same voting rights and could be the kingmakers in one of the most important Presidential swing states in 2016.

"I don't think any presidential candidate who is looking to secure Florida will be able to do that without counting on the support of the Puerto Rican communities," says Jose Luis Marantes a political activist with Mi Familia in Orlando.

"It's not enough just to be able to say a couple of words in Spanish to be able to say that you're in solidarity with the Latino community and with the Puerto Rican community. You need to speak about jobs, about health care, about education, and about opportunities for folks to come in."

By Franz StrasserBBC News, Washington

- 5 May 2015

- From the sectionMagazine

Puerto Rico's struggling economy has led to an exodus of young people moving to the US mainland - while wealthy Americans are starting to call San Juan home. As a result, the economy and identity of both places are changing in surprising ways.

While the US economy is steadily improving, Puerto Rico's unemployment rate has remained at over 13%, twice the US national average, for the last decade. The island is facing a fiscal crisis with $72bn (£47.5bn) in debt.

So the government is looking elsewhere for relief. It has started to lure America's super wealthy from the US East Coast. Two acts passed in 2012 guarantee no capital gains taxes and a mere 4% tax rate on their business to those who make Puerto Rico their primary residence.

More than 500 eligible individuals have answered the call.

"There has been some concern that we're not contributing enough on the island and not everybody is happy about that," says Robb Rill, who moved his business down in 2013.

He says the island is benefitting.

"There's probably been almost a billion dollars invested on the island since these acts have passed, and that's a billion dollars that would not have been invested on the island had there not been the proper incentives. So the everyman on the street doesn't necessarily see the direct benefit, but I can tell you that there is an immeasurable benefit not just on the real estate but through direct investment which is making a difference."

What do they get?

- No federal taxes on capitals gains

- 4% corporate tax rate on their business

Media player help

Out of media player. Press enter to return or tab to continue.

Media captionA tour of the Ritz Carlton Reserve in Puerto Rico

'Perfect storm'

This influx of mainland monied comes as tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans leave every year. They head in search of more opportunity on the US mainland, where they have the right to work as US citizens.

"What's going on in Puerto Rico right now it's the perfect storm," says Valerie Rodriguez, a young lawyer in San Juan and member of the New Progressive Party.

"You have a population in Puerto Rico where the productive sector is shrinking and the young professionals are leaving. Then you have an elderly population that's increasing in size, and obviously that population is going to depend more and more on government."

Clockwise: the Puerto Rico capitol, Orlando Rivera and his wife in Ponce, and a worker at the San Juan market

Funding those government services is a contentious issue.

"I am the worker, I am the one who is paying the taxes," says Orlando Rivera, a store manager in the city of Ponce. "I have to sustain my family, pay a 400-dollar electrical bill and my daughters' tuition fees. And in the meantime [the millionaires] aren't bringing any solutions to the problem."

Little opportunity

Jump media player

Media player help

Out of media player. Press enter to return or tab to continue.

Media captionPuerto Rico's students sound off

For those who aren't wealthy, staying in Puerto Rico is not always an option.

"Young people here that go to university and prepare themselves, they really want to stay on the island and it's not something they can do." says Ms Rodriguez.

The changing demographics are altering Puerto Rico's relationship with the mainland.

"Students that have decided to leave the island for job opportunities are important for Puerto Rico because they create other opportunities," says Uroyoan Walker, the President of the University of Puerto Rico. "It's very important that the university and the people of Puerto Rico stay connected with that diaspora so that we can become a stronger and bigger country."

The big migration

Puerto Ricans moving to the US between 2005-2012 (Source: Pew Research Center)

As citizens of a US territory, Puerto Ricans have the same right to work as any American born in the 50 states. More than 300,000 of them have left the island and headed for the US mainland in the last decade. Traditionally they have moved to New York, but more recently a third of them have moved to Florida. In Central Florida alone, 100 new families arrive every single week.

- "I miss Puerto Rico but I do not think I'm moving back there. Here there is more help here for the children, who are my priority." - Vincent Diaz Lebron

- "We came for the education. Public schools here are as good as private schools in Puerto Rico. You can have opportunities." - Jean Pierre Hernandez

- "Jobs for Puerto Ricans are very good. Not everyone is lucky enough to get a job soon but if you are bilingual and have a lot of energy, it is easy for Puerto Ricans to get a job here." - Kyana Leon

Doubling sales

This increased migration has presented an opportunity for entrepreneurs.

Titan Products of Puerto Rico opened a distribution centre in Central Florida last spring. Over 40,000 square feet of Puerto Rican products are being moved here and shipped across the Southern US.

"People used to travel there and bring back in their luggage, the cookies, the beans, or the rice," says Rafael Julia, the sales director for Titan. Alternatively, they would get products sent through the post or brought back by friends or family, she adds.

"We receive probably one to two containers a week, they come from Puerto Rico, we consolidate all the cargo down there. We have over 176 clients from small bodegas, family-owned, to big supermarkets."

They say their business is booming.

"We can double our sales next year. We are currently talking to big players like Publix and Wal-Mart to have our products there."

Popular products

- Lotus pineapple juice

- Cameo cookies

- Tacos de Mariscada

Florida, Florida, Florida

And where there's people and money the politicians won't be too far behind. Puerto Ricans residing on the mainland have the same voting rights and could be the kingmakers in one of the most important Presidential swing states in 2016.

"I don't think any presidential candidate who is looking to secure Florida will be able to do that without counting on the support of the Puerto Rican communities," says Jose Luis Marantes a political activist with Mi Familia in Orlando.

"It's not enough just to be able to say a couple of words in Spanish to be able to say that you're in solidarity with the Latino community and with the Puerto Rican community. You need to speak about jobs, about health care, about education, and about opportunities for folks to come in."

The big migration

this is the most interesting part for me. for so long the Northeast was the destination for Puerto Ricans but now Orlando is their city like Cubans in Miami. Blacks need to learn from this

Puerto Ricans moving to the US between 2005-2012 (Source: Pew Research Center)

As citizens of a US territory, Puerto Ricans have the same right to work as any American born in the 50 states. More than 300,000 of them have left the island and headed for the US mainland in the last decade. Traditionally they have moved to New York, but more recently a third of them have moved to Florida. In Central Florida alone, 100 new families arrive every single week.

Florida, Florida, Florida

And where there's people and money the politicians won't be too far behind. Puerto Ricans residing on the mainland have the same voting rights and could be the kingmakers in one of the most important Presidential swing states in 2016.

"I don't think any presidential candidate who is looking to secure Florida will be able to do that without counting on the support of the Puerto Rican communities," says Jose Luis Marantes a political activist with Mi Familia in Orlando.

"It's not enough just to be able to say a couple of words in Spanish to be able to say that you're in solidarity with the Latino community and with the Puerto Rican community. You need to speak about jobs, about health care, about education, and about opportunities for folks to come in."

]

OfTheCross

Veteran

Just had a great conversation with my mom about anti-haitianism and racism in the Dominican Republic. It's not an easy topic to bring up in a room full of Dominicans.

How'd it go?

http://southernspaces.org/2014/puer...ce-language-and-orlandos-contested-soundscape

More info on Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Florida.....really interesting

some quotes

Hispanic Population and % of the Total Population Puerto Rican Population and % of the Total Population Total Population

Seminole County 72,457 (17.1%) 34,378 (8.1%) 422,718

Lake County 36,009 (12.1%) 12,960 (4.4%) 297, 052

Orange County 308, 244 (26.9%) 149,457 (13%) 1,145,956

Osceola County 122,146 (45.5%) 72,986 (27.2%) 268,685

Buenaventura Lakes 18,160 (69%) 11,618 (44.5%) 26,079

More info on Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Florida.....really interesting

some quotes

Why do Hispanics claim a white racial identity? Rubén Rumbaut highlights the significance of place in the formation of a white racial identity, pointing out that Hispanics were far more likely to identify as white in Florida than in New York and New Jersey: in Florida 75 percent of Hispanics reported that they were white compared to only 42.1 percent in New York and New Jersey; 66.9 percent of Puerto Ricans in Florida self-reported as white compared to 45.4 percent in New York and New Jersey; Cubans were 92 percent versus 73 percent; Dominicans 46 percent versus 20 percent; Colombians 78 percent versus 46 percent; and Peruvians and Ecuadorians 74 percent versus 43 percent. Rumbaut attributes this spatial influence on racial formations to the "more rigid racial boundaries and 'racial frame' developed in the former Confederate states of Texas and Florida," which can lead to "defensive assertions of whiteness when racial status is ambiguous."64Helen Marrow claims the collective social distance from blackness "is at least partially based on the way race is organized in Latin America, where distancing from blackness is frequently encouraged." While the one-drop rule in the United States "blackened" individuals with a combination of black and white ancestry, "legacies of white superiority encourage many Latin Americans to identify as 'whiter.'"65

Hispanic Population and % of the Total Population Puerto Rican Population and % of the Total Population Total Population

Seminole County 72,457 (17.1%) 34,378 (8.1%) 422,718

Lake County 36,009 (12.1%) 12,960 (4.4%) 297, 052

Orange County 308, 244 (26.9%) 149,457 (13%) 1,145,956

Osceola County 122,146 (45.5%) 72,986 (27.2%) 268,685

Buenaventura Lakes 18,160 (69%) 11,618 (44.5%) 26,079

Last edited:

http://southernspaces.org/2014/puer...ce-language-and-orlandos-contested-soundscape

More info on Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Florida.....really interesting

some quotes

Hispanic Population and % of the Total Population Puerto Rican Population and % of the Total Population Total Population

Seminole County 72,457 (17.1%) 34,378 (8.1%) 422,718

Lake County 36,009 (12.1%) 12,960 (4.4%) 297, 052

Orange County 308, 244 (26.9%) 149,457 (13%) 1,145,956

Osceola County 122,146 (45.5%) 72,986 (27.2%) 268,685

Buenaventura Lakes 18,160 (69%) 11,618 (44.5%) 26,079

What we all knew all along, Florida hispanics suck.

OfTheCross

Veteran

The largest hispanic populations in Florida are white cubans and white PRs. It just is what it is.

Black Costa Rican congresswomen report racist threats

AFP 20 HOURS AGO

Citizen Action Party lawmaker Epsy Campbell, Dec. 15, 2014.

(Courtesy Legislative Assembly)

Costa Rican congresswomen Epsy Campbell and Maureen Clarke, both of Afro-Caribbean descent, filed complaints with the government ombudsman’s office this week after receiving a wave of racist threats in person and on social media.

The aggressions began in late April when the congresswomen asked the culture ministry to withdraw funding for a musical adaptation of the controversial novel Cocorí, by the late Costa Rican writer Joaquín Gutiérrez.

Cocorí, about a black boy who meets a white girl and embarks on a youthful adventure, has been denounced as racist by members of Costa Rica’s Afro-Caribbean community. Until recently, the book was required reading at public schools.

Campbell, of the ruling Citizen Action Party, closed her social network accounts this week after they were overwhelmed with racial insults and calls for her to “leave for Africa.” The security ministry offered her physical protection.

The legislators met on Thursday with Ombudsman Montserrat Solano, who voiced his dismay about continued racism in the country, where some 10 percent of the population is black.

“There is racism in Costa Rica and it has surfaced particularly in the past weeks, not only against the congresswomen. This is unacceptable and society must become aware,” Solano said after the meeting.

U.N. representatives and soccer player Patrick Pemberton, a goalkeeper for Alajuelense and Costa Rica’s national team, were also at the meeting. Pemberton has also been a victim of racist aggression in stadiums and on social networks.

In a communiqué, the ombudsman’s office and the United Nations said they regard “with concern the threats against persons of African descent, as well as comments hurting their dignity, especially messages of an undoubtedly racist nature.”

The Afro Costa Rican Women’s Center asked people of African descent throughout the Americas to send letters to President Luis Guillermo Solís and the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights condemning the threats against the congresswomen and demanding their protection.

Clarke, a legislator for the National Liberation Party, told daily La Nación: “In my case, I’ve become so used to it that all we want is for Costa Rica to remove the mask and admit what we are: a country that doesn’t accept diversity.”

http://www.ticotimes.net/2015/05/08...sta-rican-congresswomen-report-racist-threats

AFP 20 HOURS AGO

Citizen Action Party lawmaker Epsy Campbell, Dec. 15, 2014.

(Courtesy Legislative Assembly)

Costa Rican congresswomen Epsy Campbell and Maureen Clarke, both of Afro-Caribbean descent, filed complaints with the government ombudsman’s office this week after receiving a wave of racist threats in person and on social media.

The aggressions began in late April when the congresswomen asked the culture ministry to withdraw funding for a musical adaptation of the controversial novel Cocorí, by the late Costa Rican writer Joaquín Gutiérrez.

Cocorí, about a black boy who meets a white girl and embarks on a youthful adventure, has been denounced as racist by members of Costa Rica’s Afro-Caribbean community. Until recently, the book was required reading at public schools.

Campbell, of the ruling Citizen Action Party, closed her social network accounts this week after they were overwhelmed with racial insults and calls for her to “leave for Africa.” The security ministry offered her physical protection.

The legislators met on Thursday with Ombudsman Montserrat Solano, who voiced his dismay about continued racism in the country, where some 10 percent of the population is black.

“There is racism in Costa Rica and it has surfaced particularly in the past weeks, not only against the congresswomen. This is unacceptable and society must become aware,” Solano said after the meeting.

U.N. representatives and soccer player Patrick Pemberton, a goalkeeper for Alajuelense and Costa Rica’s national team, were also at the meeting. Pemberton has also been a victim of racist aggression in stadiums and on social networks.

In a communiqué, the ombudsman’s office and the United Nations said they regard “with concern the threats against persons of African descent, as well as comments hurting their dignity, especially messages of an undoubtedly racist nature.”

The Afro Costa Rican Women’s Center asked people of African descent throughout the Americas to send letters to President Luis Guillermo Solís and the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights condemning the threats against the congresswomen and demanding their protection.

Clarke, a legislator for the National Liberation Party, told daily La Nación: “In my case, I’ve become so used to it that all we want is for Costa Rica to remove the mask and admit what we are: a country that doesn’t accept diversity.”

http://www.ticotimes.net/2015/05/08...sta-rican-congresswomen-report-racist-threats

04SEPTEMBER 2014

BY D.L. CHANDLER

NEWS

MEXICANS OF AFRICAN DESCENT ESTABLISHED LOS ANGELES ON THIS DAY IN 1781

The Los Angeles Pobladores, or “townspeople,” were a group of 44 settlers and four soldiers from Mexico who established the famed city on this day in 1781 in what is now California. The settlers came from various Spanish castes, with over half of the group being of African descent.

SEE ALSO: Frederick Douglass Escaped From Slavery To Freedom On This Day in 1838

Governor of Las Californias, a Spanish-owned region, Felipe de Neve called on 11 families to help build the new city in the region by recruiting them from Sonora and Sinaloa, Mexico. According to a census record taken at the time, there were two persons of African ancestry, eight Spanish and Black persons, and nine American Indians. There was also one Spanish and Indian person, with the rest being Spaniards.

According to the efforts of historian William M. Mason, the actual racial makeup of the pobladores was perhaps more racially balanced than not. Mason wrote that of the 44, only two were White, while 26 had some manner of African ancestry and that 16 of the group were “mestizos” or mixed Spanish and Indian people.

Black Mexicans Luis Quintero and Antonio Mesa, the only two named on the 1781 census, married mixed women and bore several children between them.

The pobladores founded the city “El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora La Reina de los Ángeles sobre el Río Porciúncula” (Spanish for The Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels on the Porciuncula River) that day, after some priests found the area 10 years prior. Another historian, Dr. Antonio Rios-Bustamante, states that Los Angeles’ original settlers were even more mixed than the census stated, but was that African, Indian and European ancestry was a hallmark.

In Los Angeles, the El Pueblo de Los Angeles State Historic Park honored the pobladores in the 1950s with a plaque, but it was mysteriously removed. In a Los Angeles Times report, it was suggested that the removal of the plaque was racially motivated. However, in 1981 during the city’s bicentennial, the plaque (pictured) was replaced.

https://face2faceafrica.com/article/los-angeles-pobladores#.VU5sctNViko

BY D.L. CHANDLER

NEWS

MEXICANS OF AFRICAN DESCENT ESTABLISHED LOS ANGELES ON THIS DAY IN 1781

The Los Angeles Pobladores, or “townspeople,” were a group of 44 settlers and four soldiers from Mexico who established the famed city on this day in 1781 in what is now California. The settlers came from various Spanish castes, with over half of the group being of African descent.

SEE ALSO: Frederick Douglass Escaped From Slavery To Freedom On This Day in 1838

Governor of Las Californias, a Spanish-owned region, Felipe de Neve called on 11 families to help build the new city in the region by recruiting them from Sonora and Sinaloa, Mexico. According to a census record taken at the time, there were two persons of African ancestry, eight Spanish and Black persons, and nine American Indians. There was also one Spanish and Indian person, with the rest being Spaniards.

According to the efforts of historian William M. Mason, the actual racial makeup of the pobladores was perhaps more racially balanced than not. Mason wrote that of the 44, only two were White, while 26 had some manner of African ancestry and that 16 of the group were “mestizos” or mixed Spanish and Indian people.

Black Mexicans Luis Quintero and Antonio Mesa, the only two named on the 1781 census, married mixed women and bore several children between them.

The pobladores founded the city “El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora La Reina de los Ángeles sobre el Río Porciúncula” (Spanish for The Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels on the Porciuncula River) that day, after some priests found the area 10 years prior. Another historian, Dr. Antonio Rios-Bustamante, states that Los Angeles’ original settlers were even more mixed than the census stated, but was that African, Indian and European ancestry was a hallmark.

In Los Angeles, the El Pueblo de Los Angeles State Historic Park honored the pobladores in the 1950s with a plaque, but it was mysteriously removed. In a Los Angeles Times report, it was suggested that the removal of the plaque was racially motivated. However, in 1981 during the city’s bicentennial, the plaque (pictured) was replaced.

https://face2faceafrica.com/article/los-angeles-pobladores#.VU5sctNViko

Lagos locals fear annual carnival's links to Brazilian past are being lost

Streets of Nigeria’s commercial hub to fill on Saturday for annual party – the legacy of slave descendants who returned to their ancestral homeland

A reveller at the Lagos carnival in 2010. Photograph: Akintunde Akinleye /Reuters

Monica Mark in Lagos

Friday 8 May 201508.50 EDTLast modified on Friday 8 May 201519.00 EDT

Before he died earlier this year, 86-year-old great-grandfather Mr Ibaru decided he had finally had enough of Lagos’ annual carnival. “It’s become boring,” grumbled the fine-boned man with a halo of white hair, tapping his cane impatiently. “When our forefathers used to do it – that was real dancing! And we had better costumes before.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest

A group take part in the Lagos carnival. Photograph: KeystoneUSA-ZUM/Rex

When Ibaru began sewing outfits for the parades seven decades ago, the festival was closer to its origins in 19th-century rural Brazil. The annual street party arrived in Lagos via freed slaves’ descendants who returned to their ancestral homeland, including Ibaru’s own grandmother. “On the streets everyone here spoke Portuguese and ate Brazilian food,” he recalled, sitting beneath a bronze plaque of an ox’s head – the symbol of the folk festival which was transplanted to Nigeria.

On Saturday the streets of Nigeria’s commercial capital will fill for the annual Lagos carnival, the biggest and brightest in west Africa. Carnivals across the region are just one way in which tens of thousands of Brazilian – and to a lesser extent Cuban – repatriates left their mark on a crescent of nationsstretching from Sierra Leone to Nigeria. But in Lagos, some in the community fear fragile links to the past are in danger of being lost.

Brazil was the last country to abolish slavery, but had a thriving class of artisans, a jumble of those had worked their way to freedom, were of various mixed races, or were born free. Many began arriving to seek their fortunes in Nigeria at the turn of the 19th century; by 1880, almost a decade before Brazil abolished slavery, their numbers had swelled to almost one in 10 of Lagos’ approximately 40,000 inhabitants.

Outside Ibaru’s peeling yellow veranda in Lagos’ Campos district, a visitor might be forgiven for thinking they had stepped onto the streets of colonial-era Brazil: pastel-coloured houses in the distinctive Afro-Brazilian style dot the neighbourhood like bright sweets dropped amid the concrete and skyscrapers.

Mr Ibaru, pictured in Lagos before he died earlier this year, bemoaned the fact that young people were losing touch with their history. Photograph: Monica Mark for the Guardian

“Salvador, Peiro, Cruz, Veracruz, Ferreira, dos Santos,” said resident Graciano Martins, 65, rattling off the typically Brazilian surnames of his neighbours in the district also known as “popo aguda” – roughly translated as “the Brazilian quarters”.

“My parents used to talk about the food – they missed the food. Today we think of tomato, chilli and cassava as our own homegrown food, but it was [the returnees] that brought them here.” Unofficial national dishes such as eba – cassava mashed to a dough-like consistency – were adapted from the Americas, much like the English did with tea grown in India.

Those who returned came with skills and knowledge that helped make colonialLagos a buzzing melting pot and trade hub: the city was the second in the world to have street lamps, after London; a returnee who introduced piped water became one of the region’s richest men – the grand two-storey home where he lived known as Water House still stands among skyscrapers downtown; and novel ideas like Catholicism were introduced.

“There was a lot of prestige in coming back. They had money, but they would always be third- or even fourth-class citizens if they remained in Brazil,” said Sesu Tilley-Gyado, director of African Heritage Group, a foundation which last year exhibited rare photographs of Brazilian and Cuban returnees. They included an 1896 Time magazine cover showing “the league of Creole gentlemen” bedecked in Victorian-era finery.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

Drummers of the Brazilian Campos Carretta Carnival Association entertain crowds in Lagos. Photograph: Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP/Getty Images

“They wanted to help build a new world, a new Lagos. Because they were coming with money and exposure to Europeans, but also, with African heritage, they were accepted by both sides. It’s similar to what’s going on now, with many from the diaspora coming back to try to contribute to the development of the motherland,” added Tilley-Gyado, whose great-great-uncle, Oshodi Tapa, made several trips to Cuba and Brazil at the behest of the indigenous royal family, beginning in the 1830s, to encourage skilled freedmen to repatriate.

But historical links are at risk of being erased. Preservation often falls to the wayside in a frantic megacity of 21m where 4,000 newcomers pour in every day, while some have changed their Lusophone names for fear of being labelled as descendants of slaves.

“They left us a beautiful heritage and we should be proud of it,” said Olusegun Faustinho Daniel, who heads the 50-odd members of a recently-formed union, the Nigerian Descendants of Brazilians, which wants the rundown Campos area to have protected status.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

Traditional dance groups march in the carnival in Lagos last year. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

“This entire area where they stationed the returnees was all swamp before,” he said, indicating the nearby lagoon after which the Portuguese christened the city. “But they were industrious. They said, ‘We can deal with this small thing.’ If they could do that, then we can protect what they left for us,” he continued, pointing out a nearby towering church built in their distinctive style.

Still, much of the job remains in the hands of a diminishing community of elders. One afternoon shortly before he died, Ibaru called in his 33-year-old niece. He first recounted a story of how he had once met a Brazilian tourist wandering the neighbourhood, then he asked his niece to recite the family lineage going back to Brazil. She fumbled through the list under his increasingly unimpressed gaze.

“Young people don’t have any sense of history,” he sighed, rolling his eyes when she eventually stuttered to a halt.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/20...val-forgotten-links-to-brazilian-past-nigeria

Hollande to make first French president's visit to Cuba during five-day Caribbean tour

French President Francois Hollande on Thursday before leaving for the Caribbean

Reuters/Philippe Wojazer

By RFI

President François Hollande headed for the West Indies on Friday for a five-day tour during which he will make the first-ever visit by a French leader to Cuba as well as going to Haiti and France's territories in the region.

Hollande will be the first French president to visit Cuba since independence in 1898.

He will be accompanied by bosses of companies like Pernod Ricard, Air France and Accor, anxious to profit from the economic effects of the thaw in relations between the Washington and Havana.

France has voted against an embargo on Cuba at the UN since 1991, French officials were anxious to point out on Friday.

Hollande will then head to Haiti for the first official visit by a French leader since its independence - from France - in 1804, although his predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy, touched down there for several hours after the devastating 2010 earthquake.

Before all that, Hollande was due in the French territories of Saint-Barthélemy, Saint Martin and Martinique.

In Martinique he was to chair a conference on climate change, attended by leaders from the region, which contributes just 0.3 per cent of the world's greenhouse gases but is suffering the effects of global warming in rising sea levels and hurricanes.

The meeting is part of the run-up to the international conference on climate change to be held in Paris at the end of the year.

In Guadeloupe Hollande is to inaugurate what's billed as the world's biggest memorial to slaveryat a ceremony attended by Senegal's President Macky Sall, Mali's Ibrahim Bouboucar Keïta and Benin's Thomas Boni Yayi.

The building has proved controversial, both for its design, which is very modern, and its cost - 80 million euros on an island with over 26 per cent unemployment.

Several local campaign groups and lawyers have launched legal claims for compensation for the effects of slavery on a population, the majority of which is descended from Africans transported across the globe to work on colonial plantations.

http://www.english.rfi.fr/africa/20...nts-visit-cuba-during-five-day-caribbean-tour

Last edited:

GreatestLaker

#FirePelinka

Crazy

Crazy

guyana is pretty messed up, thats why the population is coming to the us in droves (especially the indians)

a quick look at their wiki page, says that Indian population is declining (prolly due to emigration) and the mixed race and native populations are increasing, while the black population is declining at a smaller rate......and with the influx of Brazilian workers they may end up looking more like the South American countries than the Caribbean

Last edited:

GreatestLaker

#FirePelinka

They aren't just moving to the US. There are Indo-Guyanese people scattered throughout the Caribbean.guyana is pretty messed up, thats why the population is coming to the us in droves (especially the indians)

a quick look at their wiki page, says that Indian population is declining (prolly due to emigration) and the mixed race and native populations are increasing, while the black population is declining at a smaller rate......and with the influx of Brazilian workers they may end up looking more like the South American countries than the Caribbean

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Every Floridian knows that shytWhat we all knew all along, Florida hispanics suck.

Last edited: