Claiming What’s Ours

On Black Americans and Cultural Appropriation

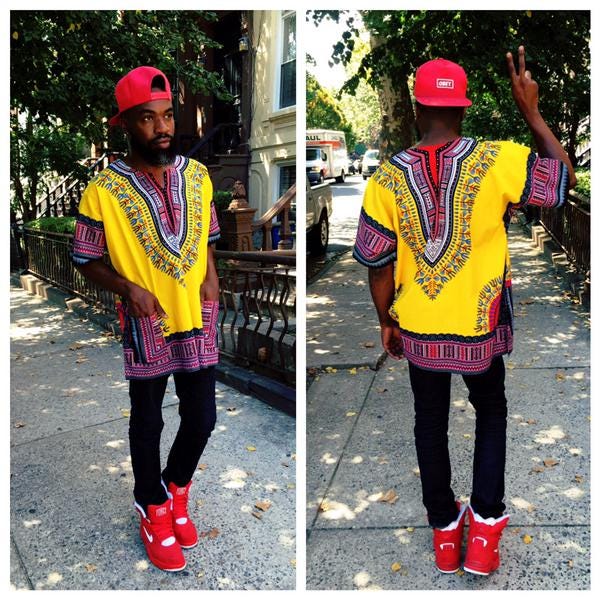

Always fresh Darnell Moore on his way to Afropunk, Source @Moore_Darnell

Recently, a Those People

post written by author Zipporah Gene posed the question, “Can Black people culturally appropriate one another?” The piece went on to answer the question by accusing African-American people of committing cultural appropriation when wearing African attire and accessories and tribal markings. While Gene may mean well, the piece did not reflect a nuanced, thorough perspective on the African Diaspora, African fashion or the topic of cultural appropriation itself. Reading the reactions and responses from folks in my network made me feel there’s a deeper discussion to be had.

To answer Gene’s initial question, yes. Black people, and really any person, can commit cultural appropriation. However, in the case of African-Americans (and others in the diaspora), the term has been misapplied.

First, Black people are connected to the African continent and one another as members of the diaspora. For many, a very important part of coming in to consciousness involves rejecting Eurocentric beauty ideals and standards and embracing African and Afrocentric styles. Black people are continually influenced by one another, trading and remixing to create new and different incarnations of cultural elements all the time. Music is the best example of this, reflected throughout jazz, funk, soul, calypso, soca, afrobeat, afropop, reggae, dancehall and house music. Though the wearing of cultural garments and accessories may sometimes come off as awkward, this is more a function of our separation, orchestrated by White Supremacy, than willful ignorance. Our knowledge is often limited because we don’t learn about a diversity of cultures and certainly not African ones.

However, cultural appropriation, it is not. Especially as Gene’s argument is framed largely on a false equivalence of comparing African-American examples of appropriation to those of White people.

A person’s relationship to the culture they are being accused of appropriating must be assessed with respect to the larger context of power in terms of systemic oppression, as well as the individual’s intent. For this reason, I would answer Gene by saying, with respect to African-Americans wearing African attire, prints and tribal markings: while Black people could possibly be cultural appropriators, they probably are not.

I take this position for several reasons. Primarily, Gene’s piece portrays African-Americans as a monolith. Though this may be a convenient framework for the accusations of appropriation, it is wholly inaccurate. African-Americans have never been monolith. Attendees of

Afro-Punk festare also a poor example on which to base a Blacks-as-appropriators argument, as

about a third of Black New Yorkers are immigrants, mostly from the Caribbean. Africans constitute about 4 percent of the city’s foreign-born population and as much as 10 percent in boroughs such as the Bronx. Many Black Americans, especially in New York, but throughout the U.S., live in mixed status families, with one or more parents or grandparents having immigrated from Africa or the Caribbean. I would venture a guesstimate that at least half of the Afro-Punk crowd (very very modest guess) are 1st and 2nd generation African, Caribbean or some mix therein. Though they may not have been paying as reverent an homage to their culture as Gene would like to see, they were fully within their right to remix and reinvent the traditional and modern stylings, because these cultural expressions are theirs by birthright.

18-year-old Kyemah McEntyre sketched and designed for her senior prom. @KyeTheCreator

For those of us who descend directly from American born and bred, free or enslaved Blacks, what Gene calls a “hodgepodge” is likely a sadly accurate description of our mixed bloodlines. Tribal affiliations, indigenous languages, spiritual and cultural practices were intentionally stripped and often violently beaten out of our enslaved forebears. Trading, and family separation further contributed to our mixed and muddled heritage. It is a testament to the human spirit of our ancestors that they were able to preserve remnants of their native food, cultural traditions, language patterns and dialects and spiritual practices, weaving them together into the vibrant and multifaceted heritage of African-American culture.

This process continues today, and wearing African attire and African patterns is a part of maintaining our ties to our ancestors, essential to our healing, empowerment and a celebration of who we are as members of the diaspora.

Restoring and maintaining ties to Mother Africa, by many means, is an ongoing and very important part of shaping Black identity. Jumping the broom, drumming, gum boot dancing (which evolved into stepping), singing and chanting in the call-and-response tradition are all African cultural practices performed throughout the diaspora. We are not appropriating what is rightfully ours, we are practicing our culture, maybe in new ways, but it is ours, nonetheless.

To the point of tribal and ceremonial markings, I do agree with Gene that spiritual and religious practices should be revered and held sacred, and should not be practiced without a thorough understanding. However, one must take into account that many of the folks wearing tribal markings are in fact fully aware of their significance, or are in the process of learning. Connecting with these traditional spiritual practices has been a strengthening force for African-Americans, from

Denmark Vesey’s storied slave rebellion to the

#SayHerName action in San Francisco this summer.

Black women organizers stage #SayHerName Action In Protest of violence against women.

Further missing from Gene’s piece is the important context that fashion and practices in Africa have been shaped and developed over time by intermixing, as well colonial conflict and imperialism.

The beloved and on-trend Ankara wax prints are not even of African origin. This beautiful fabric has origins in Indonesian invention, Indian influence and Dutch manufacturing. Of course, the brilliance of Africa took all these elements and made Ankara what it is today, a work of art and the

desire of fashion plates and pop stars across the globe.

Beyonce rocking Wax Print Image Source —

Waxing Poetic - StyleChile | Life, Styled

The hidden stories behind the beauty of our culture are marked by struggle. This is true for much of Black culture, which is why false equivalence and accusations of appropriation sting so much when it comes from a distant relative. Saying that African culture does not belong to African-Americans has the result of saying that we somehow do not belong to what many of us feel is our true, yet far off home.

When non-Black people appropriate Black culture, it draws ire, not only because they are not Black, but because they have the privilege of adding a little edge or flavor to their look or personality, without sharing any of the realities of being Black. However, African-Americans don’t have the same privilege. Whether we are rocking traditional wear, English styled cuts in African prints or even a pair of mudcloth Converse, we are not putting on an external costume, but in-fact reflecting an outward expression of what is inside of us. This cannot be denied, to paraphrase Kwame Nkrumah, first Prime Minister of Ghana,

because Africa is born in us.

The eclectically styled individuals at AfroPunk were no more appropriating African cultures than my aunties sporting coach bags and heels, speaking pidgeon, dancing to Michelle’s version of “Jesus Say Yes” and drinking Pepsi along with their Egusi are appropriating American culture.

We are a multifaceted, complex, creative and beautiful people. We are continually imagining ourselves, rediscovering, reclaiming and creating new meaning in an attempt to determine and define who we are as people.

In love, I invite my brothers and sisters on the continent and throughout the diaspora to explore ways to connect and build relationships. These conversations are important and I hope they can be a source of healing and empowerment towards further collective liberation.

I wrote this piece wearing a mass market dashiki with a label that says “made in China,” which I purchased at the “African Fashion” store run by a Somali family in Phoenix, AZ.

Claiming What’s Ours — THOSE PEOPLE

I think this topic can now be deaded

. Seriously some Africans need to get off of that egotistical I am the original mindset that they be on. I am Nigerian myself and I can't stand when I see Africans act like that. When non blacks dress in African attire they do it on some Tarzan/Jane shyt so stop getting mad at the wrong people.

. Seriously some Africans need to get off of that egotistical I am the original mindset that they be on. I am Nigerian myself and I can't stand when I see Africans act like that. When non blacks dress in African attire they do it on some Tarzan/Jane shyt so stop getting mad at the wrong people.