Revelation after revelation about the shooting death of Odin Lloyd has appeared to tighten the net around former New England Patriot Aaron Hernandez. However, defense attorneys with experience in both high-profile criminal cases and murder investigations caution against passing swift public judgment on Hernandez's fate.

Why? Because of a simple phrase we've all heard so many times it's become rote: innocent until proven guilty.

Prosecutors must prove Hernandez guilty of the crime of murder. Hernandez has no burden to prove himself innocent; at the moment, legally speaking, he's as innocent of the crime as you or me.

These are facts: Odin Lloyd, a semi-pro football player who was at least an acquaintance of Aaron Hernandez, died early on the morning of June 17 from two gunshots from a .45-caliber firearm. He was in contact with Hernandez in the hours prior to his death. But the burden of proof in tying Hernandez to the crime falls to the state, and that can be a high bar to clear.

"Jurors typically scrutinize murder cases very closely because the stakes are so high," said J. Tom Morgan, an Atlanta defense attorney who's participated (as both prosecutor and defender) in some of Georgia's most high-profile cases of recent years, and one of several defense attorneys consulted by Yahoo! Sports for this story. "You're talking about putting someone in prison for life. They will hold a prosecutor to a higher standard. Legally, there's no justification for it, but in a murder trial, the jury is much more closely attuned than they would be to, say, a car theft."

For that reason, then, the state has to be absolutely airtight in its presentation of the entire case, from determining the charges against Hernandez to laying out the facts of the case in the course of a trial. And so far, Bristol County (Mass.) prosecutors appear to have learned from another high-profile murder case involving a well-known NFL player.

"They're not going to make the mistake of rushing that was made with Ray Lewis," says Kevin Farmer, an Atlanta public defender with substantial experience in defending clients accused of murder. "They're taking their time."

Aaron Hernandez stands with his attorney, Michael Fee, during arraignment in Attleboro District Court. (AP)Lewis was arrested in 2000 in connection with a double homicide in Atlanta; in a widely-criticized case, Fulton County was only able to get a misdemeanor plea from Lewis. His two associates were acquitted of felony murder charges.

Still, even a methodical prosecution case must stand on the strength of its evidence. The evidence in Lloyd's death unsealed earlier this week indicates that police conducted a wide-ranging search in locations ranging from Hernandez's home to his temporary apartment to his Patriots locker.

"Right now, I don't see a smoking gun," Morgan said. "There's no eyewitness, no gun. There's enough probable cause to get a search warrant, but there's a long way to go to get to guilty beyond a reasonable doubt."

Because the defense hasn't yet had a chance to present its side of the case, the prosecution currently enjoys a public-relations advantage. In charging Hernandez, the prosecution laid out its reasons for pegging Hernandez as a suspect in an uninterrupted, 20-minute dialogue that aired on national television.

But viewed from a different angle, the evidence and Hernandez's actions are not necessarily indicative of a guilty man.

Consider Hernandez's demeanor when police arrived to question him about Lloyd's death. Police described him as "argumentative" and said he slammed the door in their faces when told they were investigating a death. Ten minutes later, he emerged with the telephone number of his attorney and referred all inquiries there.

"I would call that exercising his Fifth Amendment right to shut up," Farmer said. "My point of view is, when the cops asked about the murder, Hernandez did the right thing. When the police show up at your door, they're not coming to be sociable."

Immediately deferring to his attorney may not have won Hernandez points in the court of public opinion, but that's not the point. "Hernandez has been smart about not making a statement," Farmer continued. "When they tell you 'anything you say can and will be used against you,' they mean it."

Hernandez now sits in jail, awaiting indictment and, most likely, a trial. At that point, he'll face a jury, which must decide if he is guilty of murder – and here's another of those oft-repeated but nonetheless critical phrases: beyond a reasonable doubt.

It bears repeating: The defense's job is not to prove Hernandez innocent. The defense simply needs to show that there is reasonable doubt that Hernandez could have committed the crime. Defense attorneys agree that the Hernandez team's strategy could focus on any or all of three major elements of the case:

1. The victim: Shayanna Jenkins, Hernandez's girlfriend, told police that Lloyd "smoked marijuana and was also a marijuana dealer" and that she often observed Lloyd on the phone discussing what she believed were marijuana sales. That's enough fertile ground to start planting seeds of doubt, even if other acquaintances of Lloyd's denied to police he was a drug dealer. "If the deceased was a drug dealer, the crowd he's hanging with is a dangerous crowd," Morgan said. "Did he sell drugs to the wrong person or in the wrong place? There are lots of reasons you could plant in the jury's mind why someone else could have committed this crime."

2. The co-defendants: Carlos Ortiz and Ernest Wallace, two of Hernandez's associates, will likely become household names over the course of the trial. Hernandez, Ortiz, Wallace and Lloyd, according to police, were all together in a car on the night Lloyd was killed. According to documents released earlier this week, Ortiz has already flipped, cooperating with prosecutors by saying that Wallace told him Hernandez admitted firing the shots that killed Lloyd.

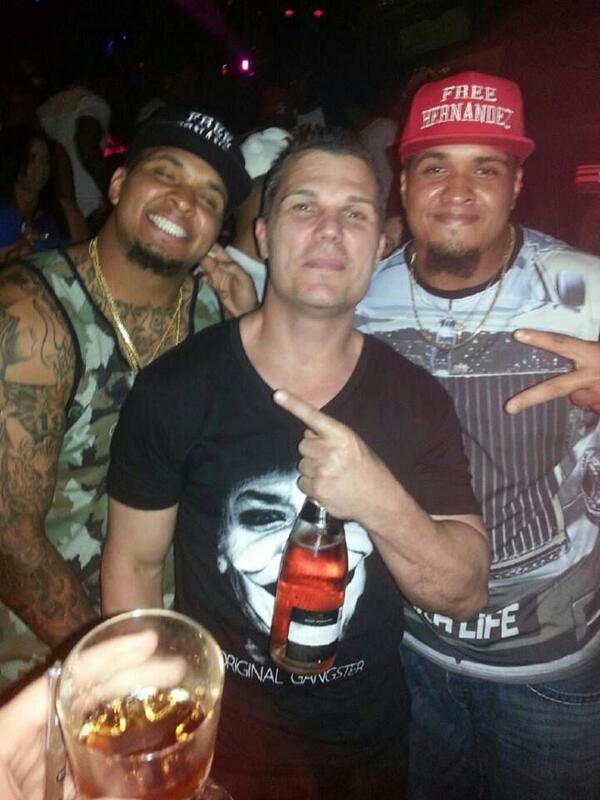

Carlos Ortiz, left, enters the Attleboro District Court with attorney John Connors. (AP)While appearing to be damning testimony, Ortiz's words are only as trustworthy as the man who speaks them. In other words, the defense will ask the jury to consider the source.

"Assuming Wallace and/or Ortiz cooperates in exchange for a lesser sentence, the defense will likely hammer away at the theme that the cooperators would do anything to avoid substantial jail time, and that those cooperators know their best chance is to blame the high-profile guy," said Glenn C. Colton, a former federal prosecutor who now heads the white collar practice at Dentons, a global law firm in Manhattan.

The strategy for the defense, then, is to go on the offensive: "Discredit the cooperating witnesses by highlighting whatever criminal history or record of dishonesty/deceit they can find on those witnesses, as well as their incredibly strong motivation to tell the prosecutors what they want to hear," Colton explained. Reports before Wallace's arrest indicate he did not have any other outstanding warrants. Ortiz reportedly has an extensive criminal history and, according to an affidavit obtained by USA Today, admitted to police he abused "PCP, alcohol and THC daily."

"Defense could also attempt to create reasonable doubt, by among other things, arguing that either of the other two key players could just as easily have committed the crime," Colton continued.

Both Ortiz and Wallace are currently in prison, Ortiz charged with illegal possession of a firearm and Wallace charged with being an accessory after the fact in Lloyd's murder. Of note: the prosecution indicated that it has not formally laid out the specifics of the night in question. "All we've done is charge Aaron Hernandez with murder," Bristol County District Attorney Samuel Sutter said Monday. "As far as the specifics about who was the shooter and who might have been a joint venturer, it's too early to say. The investigation is ongoing."

3. Evidence: Police have revealed the evidence gathered during the execution of multiple search warrants on Hernandez's property, as well as evidence gathered during the murder investigation itself. However, the .45-caliber firearm used to kill Lloyd remains missing, a hole that provides opportunity for both sides.

"The defense will seize on the absence and point out that if found, the gun could just as easily have exculpatory evidence such as another person's fingerprints," Colton said. "The prosecution, in turn, likely will argue that it was the defendant who got rid of the weapon in the first place."

Because of Hernandez's public notoriety and the graphic details of the crime, this case has captured the public's interest during a traditionally slow time of the year on the sports calendar. As the weeks roll on and football season nears, attorneys for both sides will face a choice of whether to, in effect, try the case in the media.

As a defense attorney, "you have an ethical obligation not to try the case in the press," Farmer says. "But if one side goes to the press, the other side has to respond in some way." Hernandez's defense team has already decried the prosecution's case as "circumstantial," and Farmer indicated that there's a time-tested defense strategy for responding should the prosecution continue to attempt to tarnish Hernandez in the media.

"You say, 'My client is innocent until proven guilty, and we know why they're trying this in the press, because they don't have a good case in the court,' " Farmer explained.

Hernandez's celebrity status as a local NFL star may not play as much of a role in jury selection as one might expect. Just because sports fans are following the Hernandez case doesn't mean everyone is. "Having tried high-profile cases, unless he is someone with a lot of favorable or a lot of unfavorable awareness, [Hernandez's celebrity] is probably not going to matter," Morgan said. "There will be many potential jurors who don't watch football. Lawyers and journalists would be dismayed to know how little people read the papers and follow the news."

These, then, will be the people who likely determine Hernandez's fate. All the pretrial commenting, speculating and guessing about Hernandez is irrelevant; all that matters is what happens in the courtroom, and how a jury views the presentation of both sides. In the eyes of the law, Hernandez remains innocent unless and until he's proven guilty.

. I'll tell you right now it's a lot more than 6 Patriots.

I havent been in that hole in years, thats the only place I seen that had pornos running on loop

I havent been in that hole in years, thats the only place I seen that had pornos running on loop

instead he bout to do life .

instead he bout to do life .

steez. The problem with a lot of nikkaz is that they don't have to recognize when they need to take the L. Life in prison ain't gangsta, in life you have to recognize when you need to take the L and when you can

steez. The problem with a lot of nikkaz is that they don't have to recognize when they need to take the L. Life in prison ain't gangsta, in life you have to recognize when you need to take the L and when you can  , otherwise you're just going to be food for the system.

, otherwise you're just going to be food for the system.