From 1791–1804, the Caribbean isle of Hispaniola burned and convulsed as enslaved Africans rose up in rebellion after rebellion – finally emerging as independent Haiti. Hakim Adi examines how the first successful revolution of enslaved people came to pass.

On the night of Sunday 14 August 1791, 200 enslaved Africans – representatives from a hundred plantations in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola – met to discuss plans for revolution. Fully aware of the revolution in France, and the instability it had caused within the colony, they met to decide on the date for an uprising when they would free themselves and end the entire slave system. Once a date was agreed, they held a vodou religious ceremony, against the backdrop of a violent storm. Details of this event vary, but most record the presence of Dutty Boukman, an early leader of the revolution, who told those present to “listen to the voice of liberty that speaks in the hearts of us all”.

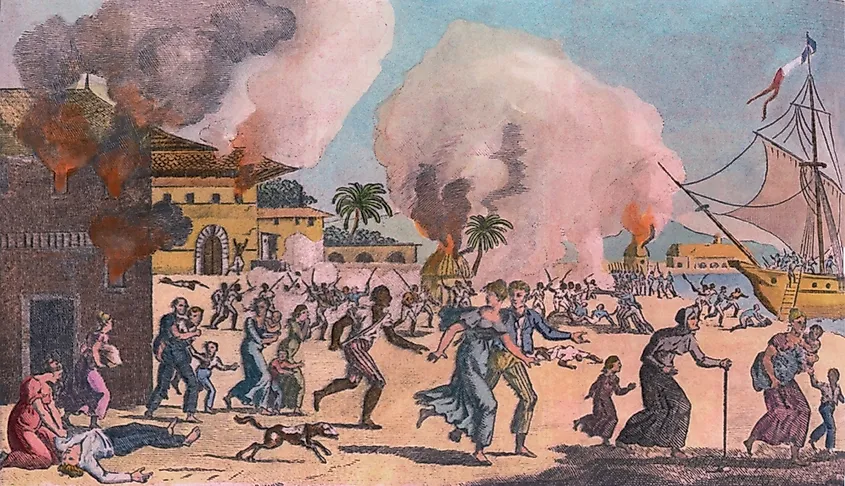

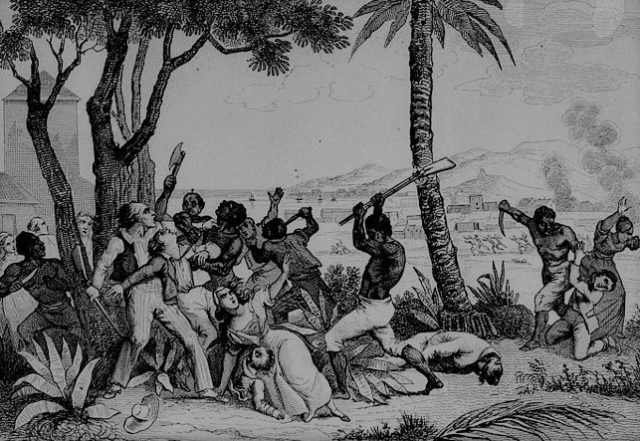

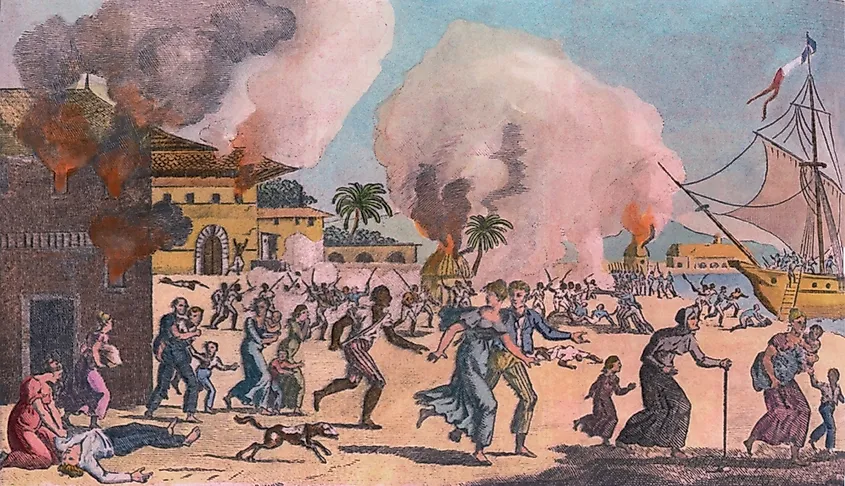

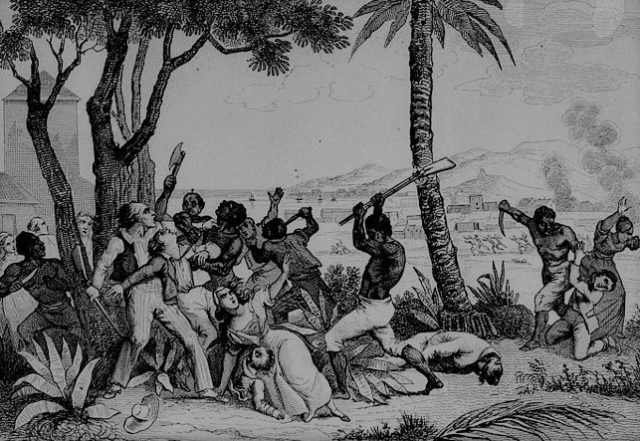

The revolution in Saint-Domingue began on the night of 22 August 1791 with the burning of plantations and the murder of the hated plantocracy. Enslaved Africans from one estate would join with those from neighbouring plantations, arming themselves with whatever weapons they could find. Within a month, the uprising was the largest ever on the North American continent, involving more than 100,000 enslaved Africans. A thousand plantations were set ablaze and more than a thousand Europeans lost their lives. The revolution would last for the next 13 years.

Saint-Domingue, on the western part of Hispaniola, had been ceded to France by Spain in 1697. By the end of the 18th century it was known as the ‘Pearl of the Antilles’, being the wealthiest of all colonies in the Caribbean, producing around half the world’s sugar and coffee, and accounting for 40 per cent of France’s overseas trade.

Saint-Domingue, on the western part of Hispaniola, had been ceded to France by Spain in 1697. By the end of the 18th century it was known as the ‘Pearl of the Antilles’, being the wealthiest of all colonies in the Caribbean, producing around half the world’s sugar and coffee, and accounting for 40 per cent of France’s overseas trade.

This great wealth was produced by 500,000 enslaved Africans labouring on more than 8,000 plantations, the largest enslaved population in the Caribbean. Enslaved Africans had first been imported by the Spanish, whose occupation of Hispaniola soon led to the near extinction of the island’s indigenous population. Such was the barbarity of the slave system developed by the French, that the average life expectancy for enslaved Africans was between seven and ten years. The enslaved population, therefore, had to be constantly replenished, by around 30,000 new Africans each year, and consequently was about 70 per cent African born.

Some 60 per cent of these Africans originated from the Angola and Kongo regions but they also included many of Yoruba, Igbo and Fon origin. On any plantation there may have been at least 20 African languages spoken. These contributed to a new common kreyòl language of communication, whilst diverse African cultures developed into the common spiritual belief known as vodou. Saint-Domingue had regularly experienced resistance to slavery, and even rebellions by the enslaved, leading to the existence of maroon communities of liberated slaves who also took part in the revolution.

The Haitian Revolution: the enslaved Africans who rose up against France